De l’art « post-Internet »

On a pu remarquer il y a déjà quelque temps l’apparition du terme « post-Internet » visant à qualifier et à analyser les pratiques d’une nouvelle génération d’artistes, nés dans les années quatre-vingt et marqués par l’influence d’Internet lors de leur formation artistique dans les années deux mille. Cette dernière décennie fut en effet celle de la démocratisation du web (avec sa version 2.0), de l’apogée des réseaux sociaux, d’un accès illimité à la connaissance et de la vente en ligne, autant d’outils propices à la création artistique à une époque où semble acquis le principe d’interdisciplinarité dans les arts visuels. Ce vocable semble cependant se concentrer sur des pratiques artistiques considérant Internet non seulement comme un outil de travail mais aussi comme une manne esthétique en soi, autosuffisante, permettant d’explorer et d’habiter l’incommensurable complexité de nos sociétés contemporaines. Si une filiation avec le Net.art est indéniable, l’art post-Internet ne doit pas être compris comme une sorte de renaissance du phénomène. Lorsque le Net.art apparaît dans le milieu des années quatre-vingt-dix à travers les expérimentations d’artistes tels qu’Olia Lialina, Vuk Ćosić ou JODI, Internet est en pleine expansion et représente un objet de découverte, aux possibilités illimitées, que ces artistes jugent bon d’exploiter à la fois comme un outil de création accessible à tous en réseau et comme un outil de résistance de par son immatérialité et ses caractéristiques virtuelles, en théorie non réifiables, face à la prépondérance du marché de l’art.

Il s’agissait d’exploiter un nouveau « site spécifique [1] » sur lequel un art « épuré » pouvait être réalisé. L’art post-Internet émerge plus d’une génération après, chez des artistes membres de réseaux sociaux, dont la dépendance aux moteurs de recherche est maintenant irréversible, avec un Macbook pour atelier et un smartphone à proximité. Ces artistes rejettent la notion d’art site-specific pour revendiquer au contraire une multiplicité de sites dans lesquels viennent circuler leurs œuvres, en un éternel va-et-vient entre réalité et virtualité, sur et hors Internet. Ils appartiennent à une génération ayant dépassé l’enthousiasme des débuts d’Internet, examiné les conséquences du phénomène et pris conscience des mutations culturelles en cours. En outre, leurs démarches considèrent acquis le principe de re-matérialisation d’un monde qui se pense pourtant immatériel (dématérialisation des transactions financières, de la communication, de l’information, des rapports humains, travail immatériel au sein d’une société de services où la production est majoritairement automatisée, etc.) puisque cette dématérialisation globale génère de nouveaux rapports physiques et psychologiques avec la production / consommation de biens matériels. [2]

DIS Competing Images, 2012. Devant / In front of The Struggle (2012) de/ by Timur Si-Qin. Courtesy DIS

Encore sujette à discussion, l’appellation « post-Internet » reste très ambiguë et peut conduire à des erreurs d’interprétation. Ce terme aurait été utilisé pour la première fois par l’artiste Marisa Olson en 2008 afin de désigner une pratique artistique qui aurait lieu « en ligne mais qui peut et devrait aussi avoir lieu hors-ligne [3] » afin de rendre compte de l’impact d’Internet sur nos vies ; il a ensuite été développé entre 2009 et 2010 grâce à une série de textes théoriques et critiques postés par Gene MacHugh sur son blog intitulé Post Internet. Dès 2008, les artistes concernés par cette nouvelle appellation commencent à se rencontrer, à se constituer en réseaux et à partager des données en ligne. Parmi ces travaux réalisés en réseau se démarque le projet Post-Internet Survival Guide [4] (initié en 2010 par les artistes Katja Novitskova et Mike Ruiz), catalyseur d’artistes ayant participé à une recherche d’images et de textes sur Internet publiés en ligne sur le blog Survival Tips puis dans l’ouvrage Post-Internet Survival Guide. Un des artistes participants, Artie Vierkant, publie la même année The Image-Object Post-Internet [5], un texte cherchant à apporter une définition à l’art post-Internet afin d’y situer sa pratique et d’en expliquer les fondements. Le terme se répand ensuite à travers l’utilisation qui en est faite par les artistes, critiques et commissaires d’exposition, et devient emblématique de cette nouvelle génération associée à Internet. Sa définition peine cependant à se stabiliser et continue à évoluer ce qui, d’après l’artiste Jaakko Pallasvuo, semble de bon augure : « Je préfère que les gens soient en désaccord à propos de cette définition. J’espère que le terme post-Internet restera toujours l’objet de débats au lieu de se figer dans un concept historique univoque [6] ».

La diversité des démarches associées à cette nébuleuse découle des multiples possibilités offertes par le net. Le dénominateur commun se trouve certainement dans l’intérêt porté à la distribution, la circulation et l’exploitation de l’information en ligne. La démonstration d’Oliver Laric avec Touch My Body : Green Screen Version (2008) est particulièrement éloquente à ce sujet : réalisée à partir du clip de la chanson éponyme de Mariah Carey trouvé sur YouTube, cette vidéo a été dépouillée de tout son arrière-fond pour ne laisser place qu’à la chanteuse sur fond monochromatique (technique utilisée à la télévision ou en informatique afin de rajouter des fonds factices au montage). L’artiste a ensuite posté sa version piratée du clip pour la livrer à la merci de tous les internautes, libres d’y intégrer n’importe quels types de fonds, des plus frustes aux plus élaborés. Rapidement, plus d’une centaine de nouvelles versions du clip ont alors été dénombrées par l’artiste qui en a compilé certaines sur son site. Libres d’utilisation, ces vidéos sont exploitées et réexploitées, circulant de blog en blog et de site en site. Cette expérience révèle un point important à savoir le devenir des droits d’auteur et de la propriété intellectuelle à l’heure du web 2.0, en particulier concernant les œuvres d’art. Comment protéger une œuvre immergée dans un environnement soumis au principe du partage ? Kopienkritik, exposition à la Skulpturhalle de Bâle (2011) dans laquelle l’artiste mêlait des moulages de sculptures grecques et de leur copies romaines à ses œuvres, produisait justement un intéressant parallèle entre les conceptions de l’Antiquité et les nôtres : les sculpteurs romains copiaient les classiques grecs aussi librement que nous copions-collons.

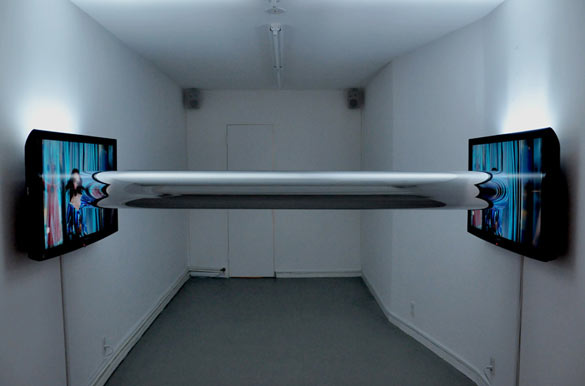

Antoine Catala. Topologies, 2010. Vidéos, écrans numériques / Video, digital picture frame. Dimensions variables. Courtesy 47 Canal, New York

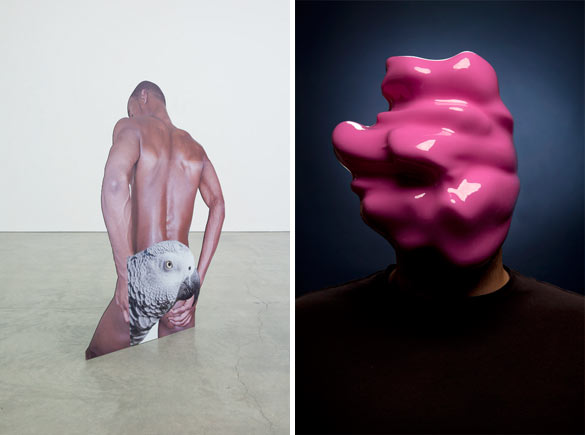

Timur Si-Qin. Selection Display: Gender Dimorphic, 2013. Impression sur PVC et aluminium sur socle / Print on PVC, Aluminium, pedestal 243,5 x 410 x 170 cm. Courtesy Timur Si-Qin ; Société, Berlin

Les blogs ou Tumblr créés collectivement par ces artistes adoptent le format classique du partage en ligne et témoignent de la manière dont les données sont, grâce à Photoshop et autres logiciels, constamment retouchées, transformées et réutilisées ; nous noterons parmi eux : vvork.com, r-u-ins.tumblr.com, thejogging.tumblr.com, xym.no, thestate.tumblr.com et survivaltips.tumblr.com. Visuels d’œuvres, photos sélectionnées sur des banques d’images ou trouvées sur des blogs insolites, ces images vraies ou fausses sont parfois réexploitées et transformées par d’autres artistes. Des vues d’expositions se voient ainsi envahies par des objets intrus, apportant une touche d’humour au sérieux des accrochages. Spécialisé dans la manipulation des codes instaurés par les banques d’images, le collectif DIS [7] caricature ce type d’imagerie afin de créer de nouveaux types de narration et de nouveaux stéréotypes. DIS a investi en 2012 l’exposition de Katja Novitskova et Timur Si-Qin aux CCS Bard Galleries pour une séance photo, Competing Images (2012), mettant en scène des modèles vivants posant aux côtés des installations, à la manière dont les internautes trafiquent des images en y accolant des éléments. La « retouche Photoshop » avait donc lieu physiquement pour finalement produire une image en ligne semblable aux autres. Il est troublant de constater que ces images, originales ou artificielles, voisinent sur les mêmes plateformes d’échange sans démarcation, dans un contexte où la majorité des œuvres d’art et des expositions sont appréciées grâce aux images en ligne. Ceci corrobore en partie la démarche d’Artie Vierkant dans son projet Image Objects (2011-en cours). Les œuvres de cette série ont toujours pour origine une image qui, une fois apposée sur dibond, existe physiquement pour être accrochée dans le lieu d’exposition. Lorsque vient le moment de documenter l’œuvre par la photographie, Vierkant en altère l’image sur Photoshop, lui donnant ainsi une nouvelle forme et une nouvelle existence. La perception que peut en avoir le spectateur est par conséquent déstabilisée par une œuvre aux formes multiples bien que physiquement intacte. La démarche de l’artiste annule de fait toute hiérarchie entre l’œuvre réelle et son image puisque celles-ci sont dorénavant appréhendées à égalité.

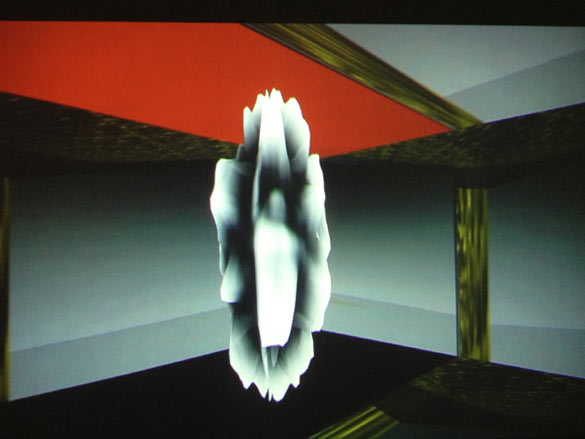

Kari Altmann, quant à elle, s’approprie le langage de la communication technologique grâce à des compilations d’images et de vidéos rassemblées sur son site internet. Ses créations en ligne se veulent en perpétuelle évolution et ne sont pas externalisées, à moins que cela lui soit proposé pour une exposition. L’œuvre change alors d’état sans que sa version en ligne en soit affectée : son travail exposé hors ligne — par le biais d’un moniteur vidéo ou d’une impression — est toujours visible en ligne, et le sera encore après l’exposition. L’artiste ne considère d’ailleurs pas ses présentations hors ligne comme des « expositions » mais comme un autre mode d’existence pour ses réalisations qui sont au fond continuellement exposées. Cette relativisation de l’espace d’exposition comme fin en soi se manifestait encore dans Exhibition One à laquelle a participé Kari Altmann, une exposition organisée par Timur Si-Qin en 2010 dans un white cube en image de synthèse, la « Chrystal Gallery ». La question de savoir où se termine l’œuvre et où commence sa documentation se voyait par conséquent contrebalancée par une création digitale incluant les deux phénomènes à la fois [8].

La circulation aller-retour des images, à l’intérieur et hors des écrans, prend pertinemment forme dans Topologies (2010) d’Antoine Catala. Accrochés face à face, deux écrans plasma sont reliés par un large tube dont les extrémités sont recouvertes d’une surface miroitante, reflétant et déformant les images diffusées. Ce flux d’informations passant d’un écran à l’autre sans relâche, apparaît telle une structure technologique de pointe informe, à la fois fascinante et menaçante.

Grâce au succès de la vente en ligne, les biens de consommation font maintenant partie intégrante de cette diffusion. L’installation Parasagittal Brain (2011) d’Yngve Holen invite le visiteur à pénétrer entre deux longs rayons sur lesquels se succèdent des objets usuels — bouilloires, purificateurs d’eau, fers à repasser, etc.— qui ont la particularité d’être divisés en deux pour que chaque partie soit placée de part et d’autre du passage. Leurs entrailles sont ainsi crûment déployées bien que leur présentation demeure parfaitement symétrique et leur découpe, sans bavure. Parfaitement neufs d’un côté, ces objets sont néanmoins inopérants, ils exhibent ainsi leur inutilité et leur remplacement à venir, exécutable en quelques clics. Avec Planned Fall (2013) Aude Pariset crée une inquiétante atmosphère dans laquelle des mannequins de présentation habillés de vêtements en putréfaction semblent sur le point de s’engouffrer dans des sacs poubelles : détournant les codes de la présentation commerciale, cette installation déroute les habitudes et les désirs compulsifs du « prosommateur » contemporain. Tels des bocaux de formol, les cubes de plexiglas de Sean Raspet conservent les objets les plus divers — et même des impressions numériques — dans du gel de coiffage translucide, rappelant l’atmosphère aseptisée des laboratoires.

Si admettre que le progrès technologique génère des mutations comportementales et morphologiques chez les êtres humains frise aujourd’hui le truisme, ajoutons qu’Internet a largement contribué à généraliser cet état de fait. Les ordinateurs portables et les smartphones sont désormais des prothèses qui fonctionnent chez nous comme des organes supplémentaires, ou plutôt des « extensions de nous-mêmes », comme l’aurait fait remarquer McLhuan. Nous finissons par penser selon leur mode de fonctionnement, et devenons littéralement PC, Macbook ou smartphone. N. Katherine Hayles précise que si les avancées technologiques de l’information ne peuvent pas fondamentalement remplacer le corps humain, ces dernières peuvent parfaitement l’incorporer, y compris nos habitudes quotidiennes [9]. Les Timetables (2011) d’Anne de Vries présentent un ensemble de tablettes imprimées de ciels nuageux sur lesquelles gisent des mains / smartphones en céramique évoquant la multiplicité des connexions de type « cloudcomputing » apparaissant et disparaissant au gré des besoins, activées par des prothèses fonctionnant comme des organes supplémentaires. Si telles sont représentées les mains de l’homme du XXIe siècle, il convient de voir ce qu’il en est de son portrait, et notamment ceux de la série N.A.D (NewAgeDemanded) (2012-en cours) « sculptés » par Jon Rafman. Reprenant la forme classique du buste, l’artiste dresse une série de portraits hybrides que l’accélération du temps présent empêcherait de figer. À la fois virtuels et réels, ces bustes intègrent « les champs de déplacements, de mutations et de mouvement » renégociant le principe de représentation dans un « milieu informationnel [10] ». Les réseaux sociaux, les blogs, les Tumblr ou Instagram permettent à quiconque d’être en constante représentation. Jaakko Pallasvuo signale que ces sites offrent aussi le moyen de se construire des identités et de s’inventer un avatar [11] : sa vidéo Reverse Engineering (2013) le représente sous différentes identités, parlant de lui-même et de son expérience en tant qu’artiste du XXIème siècle à l’aide de plusieurs voix et visages, filmés à la webcam. Il s’agit d’une vidéo postée sur Youtube semblable à des millions d’autres grâce auxquelles de nombreux utilisateurs pensent accéder à la célébrité. Pourtant l’accès au « profil » de l’artiste ne se fait pas grâce à l’image mais par un discours beaucoup plus représentatif de sa personnalité, obscurcie par une quantité de visages et d’images qui perturbent les habitudes de ciblage du web. Katja Novitskova donne également un bon aperçu de la manière dont égocentrisme et exhibitionnisme s’accordent avec les systèmes de représentation de soi disponibles en ligne.

Les collages digitaux de la série Earth Call 1 & 2 (2012), associant des paysages trouvés sur Google Earth à des selfies de jeunes hommes postés sur Tumblr, soulignent la sophistication de soi grâce aux retouches et corrections rapides permises par la technologie. Ils illustrent ce que pourrait être le « souci de soi » du XXIème siècle. Le genre du paysage se renouvelle de même : captivée par Second Life, les jeux vidéo et les images d’habitat standard, Sara Ludy propose des vidéos dans lesquelles le regard flotte nonchalamment dans des paysages virtuels en perpétuel devenir. Sphere 1-20 (2013) consiste en la projection d’un objet flottant non identifié au centre d’un espace mouvant qui, chaque minute, mute et tourne sur lui-même dans un nouveau décor. Désertés par tout type d’être vivant, ses environnements immersifs sont des zones psychologiques et méditatives à investir.

Parmi ces pratiques dites « post-Internet », nombreuses sont celles penchant vers une lecture archéologique du progrès technologique, à l’instar d’Aleksandra Domanovic qui parcourt l’histoire récente de la Yougoslavie, son pays natal, à travers le prisme d’Internet. Intitulée « From yu to me », son exposition à la Kunsthalle de Bâle (2012) témoignait d’une forte attache à la mémoire de cette nation désormais disparue ainsi qu’aux dérèglements identitaires et culturels ayant suivi. Utilisé pour la Yougoslavie, le domaine .yu fut supprimé en 2010 et remplacé par autant de domaines qu’il y a de nouvelles nations. Cet acte représente pour l’artiste l’ultime élimination de son pays dans un contexte politique mondial où l’adresse du domaine compte dorénavant plus que l’hymne national. La série de sculptures issues du projet The Future Was at Her Fingertips (2013), représentant des prothèses de mains sur de hauts piédestaux en plexiglas, s’inspire des expérimentations de Rajko Tomovi qui chercha à rendre le sens du toucher aux soldats amputés lors de la Deuxième Guerre mondiale grâce à un procédé d’intelligence artificiel. L’artiste aspire ici à dévoiler l’importance du travail pionnier de femmes comme Ada Lovelace, Sadie Plant ou Borka Jerman Blazi dans les développements et la création de la cybernétique, de la réalité virtuelle, des multimédia et d’Internet. C’est également une femme, ou plutôt son image, qui fut pour la première fois photoshopée en 1987 comme nous le rappelle le projet Jennifer in Paradise (2013) de Constant Dullaart. Représentant une femme topless sur une plage de Bora-Bora, agrandie puis affichée sur un mur par l’artiste (laissant percevoir la trame des pixels), cette photographie fut prise à titre expérimental par John Knoll, co-créateur de Photoshop, afin de prouver l’efficacité de son logiciel ; l’exhumation de cette image nous remémore une époque où l’authenticité des images était encore envisageable.

Anne de Vries. Timetables, 2011. Bois, métal, céramique, tirages photo numériques / Wood, metal, ceramic, digital photo prints. Dimensions variables. Courtesy Anne de Vries

Les spéculations concernant le futur sont également récurrentes chez ces artistes. Dans son texte A Million Years of Porn, Timur Si-Qin s’appuie sur la théorie de la sélection sexuelle pour expliquer comment certaines espèces changent de morphologie en fonction des critères physiques recherchés lors de l’accouplement, tels que les caractères indicateurs de fertilité ou les signes de résistance aux parasites. Reportant ce principe à l’espèce humaine, l’artiste constate parallèlement qu’en 2006, 97,06 milliards de dollars ont été dépensés à l’échelle mondiale dans la consommation pornographique et que 25 % des recherches sur internet concernaient ce domaine. Il en conclut que les êtres humains sous influence chercheront à l’avenir des partenaires dotés d’attributs physiques semblables à ceux des acteurs porno, ce qui pourrait contribuer à faire évoluer l’espèce humaine ainsi : dans 69 millions d’années, les femmes auront des corps imberbes aux poitrines généreuses et les hommes, une musculature parfaite et des sexes démesurés [12]. L’actualisation des théories évolutionnistes combinée au réalisme néo-matérialiste de Manuel de Landa apportent également à Katja Novitskova les outils conceptuels nécessaires à sa vision anthropocéniste du monde. La publication issue du projet Post-Internet Survival Guide se présente comme un guide de survie face aux multiples changements auxquels sont actuellement confrontés non seulement l’espèce humaine mais aussi les organismes composant la planète Terre : « la notion de guide de survie se conçoit telle une réponse à un besoin humain élémentaire, visant à faire face à une complexité croissante. Face à la mort, aux attaches personnelles et au désordre, chacun se doit de sentir, d’interpréter et d’inventorier cet océan de signes afin de survivre. [13] » D’autres écrits de l’artiste rappellent que les principes d’attraction et de répulsion, concepts clés de la biologie évolutionnaire, sont aussi bien applicables au domaine de l’art. La vue des animaux a toujours stimulé l’instinct de survie des êtres humains ainsi que leurs réactions affectives. Issu d’un processus évolutif autonome, l’art produit aussi de fortes réactions émotionnelles chez l’homme, bien que pour des raisons différentes. Afin d’explorer ce rapport, Novitskova a réalisé une série de sculptures intitulée Approximation (2012-en cours), de très séduisantes images d’animaux plaquées sur des supports publicitaires destinées à produire chez le spectateur une réaction émotionnelle attribuée à un lointain atavisme. Elle en déduit que ces images d’animaux représenteront bientôt de puissantes ressources, comme l’atteste Intensive Differences 003 (2012), un papyrus sur lequel est imprimé une image de Justin Bieber photographié à côté d’un dauphin afin de promouvoir sa marque de vêtements, argumentant par là que l’intensité produite à la vue de ces images pourrait devenir une source d’énergie exploitable dans un avenir proche. [14]

Rappelons que cette génération d’artistes évolue dans un système économique néolibéral dérégulé qui, bien qu’en crise, parvient toujours à se maintenir. La puissance financière difficilement maîtrisable par les États s’apparente à un flux rapide et insaisissable expliquant certainement pourquoi les liquides et les fluides – ou leurs représentations – sont si présents dans les œuvres. La dématérialisation monétaire à l’œuvre depuis la fin des accords de Bretton Woods a contribué au façonnage d’un système financier dans lequel la monnaie n’a qu’une valeur fictive. Les paiements par carte ou PayPal concourent à cette fluidité des transactions. Les principes postfordistes de l’économie numérique permettent la déterritorialisation des capitaux et l’implantation de firmes high-tech telles que Google, Amazon ou Microsoft dans des paradis fiscaux afin d’éviter l’imposition des pays dont ils tirent profit. Le duo AIDS 3D (Daniel Keller / Nik Kosmas) s’intéresse à ces nouveaux aspects de l’économie globalisée : Absolute Vitality Inc. (2012) précise sans détour la participation du marché de l’art à ce système. Semblable à une plateforme de conférences et de rencontres, cette installation se veut l’organe promotionnel d’une société rachetée en 2012 par les artistes à un fournisseur de services pour sociétés-écrans, localisée à Cheyenne dans le Wyoming (USA). Pensée comme un support multifonction pour leurs projets à avenir, cette société a pour principal objectif d’employer une stratégie à plusieurs volets de croissance diversifiée, permettant à des collectionneurs d’investir dans des œuvres d’art à moindre risque, avec un maximum de retour sur investissement. Par ailleurs, les artistes ont avancé l’idée de concevoir des œuvres à partir du « data-mining » utilisé par les agences de marketing pour cibler de potentiels consommateurs : « […] nous utiliserons un logiciel comme Lexalytics pour faire des analyses sémantiques à partir d’écrits sur l’art dont l’objet sera de créer des descriptions d’œuvres d’art “significatives”. Ensuite un spécialiste nous aidera à écrire des algorithmes qui, à partir de ses descriptions, donneront des instructions utiles à la conception de nouvelles œuvres d’art. Enfin, nous exposerons ces œuvres d’art et nous analyserons les opinions et réactions qu’elles produiront sur le public. [15] » Notons que, dans un entretien entre Jaakko Pallasvuo et Jean Kay, les deux s’accordent sur les similarités existant entre l’interdisciplinarité caractérisant l’art actuel et la capacité du capitalisme tardif à tout s’approprier, même sa critique. [16]

Création, économie et technologie de pointe font d’ailleurs l’objet d’importantes rencontres, à l’instar des conférences TED (Technology, Entertainment and Design) ou du plus récent DLD (Digital-Life-Design), réunissant des artistes aux startups et aux personnalités les plus innovantes, afin de partager expériences et idées à propos de l’avenir de notre société. Concerné par l’influence du progrès technologique sur nos façons de communiquer, Simon Denny collabore en 2013 avec Daniel Keller pour organiser un événement TEDx, suite à l’invitation du Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein, dans la ville de Vaduz. Adoptant à la lettre le format et le contenu des rencontres TEDx, les artistes ont dessiné le plateau de conférence usant des codes de communication à l’œuvre dans ce type d’événements. S’y sont succédé neuf participants issus des domaines créatifs, juridiques, économiques et politiques, disposant chacun de douze minutes pour présenter leurs démarches et idées novatrices au public. À partir d’un format idéologique très prisé, bien que critiqué pour ses partis-pris pseudo-scientifiques, TEDxVaduz se présente comme une fausse parodie ayant pour objectif l’analyse des valeurs, de l’esthétique et des tendances véhiculées par l’économie technologique.

Il se dégage des pratiques évoquées ci-dessus le reflet d’une situation historique troublante, voire inquiétante, liée à d’importants changements de paradigmes à l’origine desquels se trouvent être Internet et les nouvelles technologies. Face à de tels constats, nous pourrions nous attendre à des œuvres à fort contenu critique dénonçant l’avenir vers lequel la culture numérique semble nous projeter. Ce n’est cependant pas dans ce sens que se dirigent les démarches de la plupart de ces artistes qui, selon Constant Dullaart, laisseraient ce travail aux activistes pour produire des œuvres prétendument « post-Internet » alors que celles-ci « sont toujours montrées dans le plus hiérarchisé et le plus conservateur des médium que le monde de l’art puisse offrir : le white cube. [17] » Mais l’un peut-il vraiment empêcher l’autre ? La démarche de Constant Dullaart tend à souligner par ailleurs qu’Internet n’est plus la « zone d’autonomie temporaire [18] » support d’une culture politique alternative qu’il a été dans les années quatre-vingt, ni l’espace de liberté tant vanté par les médias, ces derniers rapportant par exemple que les révolutions arabes n’auraient jamais pu se faire sans Facebook… Internet représente maintenant le principal instrument de la « société de contrôle » annoncée par Gilles Deleuze comme le démontrent les dernières déclarations de la NSA, ou l’inextricable situation de Julian Assange, Chelsea Manning et Edward Snowden. Comment Internet pourrait donc être plus pertinent qu’une salle d’exposition pour réagir et résister ? En tant qu’artiste explicitement engagé, Zach Blas ne semble pas se poser la question. Son projet Facial Weaponization Suite (2011-en cours) réagit à la banalisation des procédés biométriques de reconnaissance faciale. Il consiste en une série de masques conçus à partir des données faciales de différents sujets, insondables par les systèmes de lecture biométrique. Parmi ces masques, le Fag Face Mask (2012), produit à partir des données faciales d’homosexuels, tend à résister aux récentes études scientifiques postulant qu’il est possible de déterminer les orientations sexuelles des sujets grâce à la biométrie. Portés lors de grands rassemblements sociaux ou de performances, ces masques se conçoivent comme des accessoires opaques de transformation collective, contestant les formes dominantes de représentation politique. Le white cube et Internet demeurent cependant des moyens tout aussi viables de dissémination stratégique pour l’artiste. Cette pluralité des modes de présentation n’altère en rien la pertinence de la portée critique de son engagement. On aurait donc tort de sous-estimer la conscience politique de cette génération et de réduire son travail à un froid dédoublement de l’imagerie d’Internet dans les galeries marchandes. Car ces pratiques peuvent peut-être nous éclairer sur un certain déplacement du combat politique qui ne s’envisagerait plus comme nous le pensions. Peut-être ont-elles trouvé une manière d’« atteindre le corps sans organes, sans déstratifier à la sauvage [19] ». Il faudrait alors y percevoir en creux des postures se situant désormais à un autre niveau conceptuel que celles, éculées, de l’activisme traditionnel.

- ↑ Josephine Berry-Slater réhabilite la notion de site-specificity pour qualifier les expérimentations des artistes du Net.art lors du colloque Post-Net Aesthetics qui s’est tenu en octobre 2013 à l’ICA, Londres.

- ↑ Joshua Simon, Neomaterialism, Sternberg Press, Berlin, 2013, p. 17.

- ↑ « Interview with Marisa Olson », We Make Money Not Art, 28 mars 2008. (traduction de l’auteur)

- ↑ Post-Internet Survival Guide, dirigé par Katja Novitskova, Revolver Publishing, Berlin, 2011.

- ↑ Artie Vierkant, The Image-Object Post-Internet, 2010.

- ↑ Careers are last season: An interview with Jaakko Pallasvuo, par Tim Gentles, p. 62. (traduction de l’auteur)

- ↑ disimages

- ↑ Chrystal Gallery

- ↑ N. Katherine Hayles, How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature and Informatics, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1999.

- ↑ Tiziana Terranova, Network Culture : Politics for the Information Age, Pluto Press, New York, 2004, p. 7, citée par Ceci Moss dans « Expanded Internet Art and the Informational Milieu » paru sur le site RHIZOME, décembre 2013. (traduction de l’auteur)

- ↑ « An interview with Jaakko Pallasvuo » sur aqnb, 31 mai 2013.

- ↑ Timur Si-Qin, « A Million Years of Porn » dans The future will be… China: impromptu thoughts on what’s to Come, Éd. Pinacoteca Agnelli, Turin et UCCA, Pékin, 2012.

- ↑ Post-Internet Survival Guide, op. cit., p. 4 (traduction de l’auteur).

- ↑ Voir à ce propos l’intervention orale de Katja Novitskova lors de la rencontre TedxVaduz organisée par Simon Denny et Daniel Keller au Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein, 7 décembre 2013.

- ↑ « KELLER/KOSMAS (AIDS-3D) interview by Simon Denny », KALEIDOSCOPE/Web Specials, 2012 (traduction de l’auteur)

- ↑ « An interview with Jaakko Pallasvuo » sur aqnb, cf. supra.

- ↑ « Beginnings + Ends », Frieze, n° 159, novembre-décembre 2013, p. 127.

- ↑ Hakim Bey, The Temporary Autonomous Zone : Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism, New York, Éd. Autonomedia, 1991.

- ↑ Gilles Deleuze et Felix Guattari, Mille Plateaux, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1980, p. 199.

On “post-Internet” Art

Some time ago the term “post-Internet” came to our attention, used to describe and analyze the activities of a new generation of artists, born in the 1980s and marked by the influence of the Internet during their artistic training in the 2000s. This last decade in fact witnessed the democratization of the web (with its 2.0 version), the peak of social networks, unlimited access to knowledge, and online sales, all tools favourable to artistic creation at a time when the principle of inter-disciplinarity in the visual arts seems to be a given. Yet this term, post-Internet, seems to focus on art praxes which regard the Internet not only as a work tool but also as an aesthetic godsend per se, both self-sufficient and making it possible to explore and inform the boundless complexity of our contemporary societies. There is an undeniable connection with Net-art, but post-Internet art should not be understood as a kind of rebirth of the phenomenon. When Net.art appeared in the mid-1990s by way of experiments undertaken by such artists as Olia Lialina, Vuk Ćosić and JODI, the Internet was expanding a-pace and represented an object of discovery, with unlimited possibilities, which those artists deemed ripe for making the most of, both as a creative tool accessible to one and all in network form, and as a tool of resistance through its immaterial nature and its virtual and, in theory, non-reifiable features, in the face of the predominance of the art market.

What was involved for those artists was making use of a new “site specific” [1] basis on which a “purified”, “spare” art could be produced. Post-Internet art emerged more than a generation later, among artists belonging to social networks, whose reliance on search engines is now irreversible, with a Macbook as their studio and a smartphone close by and at the ready. These artists reject the notion of site-specific art and, on the contrary, lay claim to a whole host of sites in which their works circulate, in an endless to-and-fro between reality and virtuality, on and off the Internet. They belong to a generation that has gone beyond the enthusiasm of the Internet’s early days, taken a close look at the phenomenon’s consequences, and become aware of the various cultural changes under way. What is more, their approaches and methods regard as acquired the principle of re-materializing a world which nevertheless thinks of itself as immaterial (de-materialization of financial transactions, communication, information, human relations, and immaterial work within a service-oriented society where production is for the most part automated, etc), because this overall de-materialization gives rise to new physical and psychological relations with the production/consumption of material goods. [2]

The term “post-Internet”, which is still up for discussion, remains very ambiguous and can lead to mistaken interpretations. The term was supposedly first used by the artist Marisa Olson in 2008, to describe an artistic praxis taking place “…on networks but can and should also exist offline”, [3] in order to realize the Internet’s impact on our lives. The term was subsequently developed between 2009 and 2010 thanks to a series of theoretical and critical writings posted by Gene MacHugh on his Post Internet blog. In 2008, artists concerned by this new designation started to meet, form networks, and share online data. Among works produced in networks, the project Post-Internet Survival Guide stands out (initiated in 2010 by the artists Katja Novitskova and Mike Ruiz), a catalyst for artists who had taken part in an Internet search for images and texts published online on the Survival Tips blog, then in the book Post-Internet Survival Guide. [4] That same year, one of the participating artists, Artie Vierkant, published The Image-Object Post-Internet, [5] a text seeking to give a definition to post-Internet art in order to situate its praxis and explain its bases. The term then spread as a result of the use made of it by artists, critics and exhibition curators, and became emblematic of this new Internet-associated generation. But its definition is having trouble becoming constant, and is still evolving, which, according to the artist Jaakko Pallasvuo, seems to bode well: “I like that people are disagreeing on its definitions and with each other. I hope post-Internet will begin to stand for this continuous debate instead of being cemented into an art historical one-liner.” [6]

Katja Novitskova. Innate Disposition, 2012 (gauche/left). Impression numérique sur aluminium, support plastique / Digital print plastic cutout displays. Vue de l’exposition au / Installation view at the Center for Curatorial Studies: Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY /// Zach Blas. (droite/right) Facial Weaponization Suite: Fag Face Mask – October 20, 2012, Los Angeles, CA. Courtesy Zach Blas. Photo : Christopher O’Leary

The diversity of the approaches associated with this nebula stems from the many different possibilities offered by the Internet. The common denominator undoubtedly lies in the interest attaching to the distribution, circulation and use of information online. Oliver Laric’s demonstration with Touch my Body: Green Screen Version (2008) is especially eloquent on this subject: made from the clip of Maria Carey’s song of the same title, to be found on YouTube, this video has been stripped of its whole backdrop, leaving room just for the singer against a monochromatic background (a technique used on television and in computers to add artificial backdrops to the editing). The artist then posted his pirated version of the clip and left it at the mercy of all web-surfers, free to add any kind of backdrop, from the crudest to the most elaborate. In no time at all, more than a hundred new versions of the clip were then counted by the artist, who included some of them on his website. These freely used videos are made use of again and again, circulating from blog to blog and website to website. This experience reveals an important point, to wit, the future of royalties and intellectual property in the age of web 2.0, especially where artworks are concerned. How is it possible to protect a work immersed in an environment subject to the principle of sharing? Kopienkritik, a show at the Basel Skulpturhalle (2011), in which the artist mixed casts of Greek sculptures and their Roman copies with his own works, produced, it just so happens, an interesting parallel between the conceptions of Antiquity and ours: Roman sculptors copied the Greek classics as freely as we copy-and-paste.

The blogs and Tumblr micro-blogs collectively created by these artists adopt the classic format of online sharing and, thanks to Photoshop and other software systems, illustrate how the data are being constantly re-touched, transformed and re-used. Among these latter, we might note vvork.com, r-u-ins.tumblr.com, thejogging.tumblr.com, xym.no, thestate.tumblr.com and survivaltips.tumblr.com. These images, true or false, are visuals of works, photos selected from image banks or found on unusual blogs, and they are sometimes re-used and transformed by other artists. Views of exhibitions can thus be invaded by intruding objects, adding a dash of wit to the seriousness of hanging works. The DIS collective, [7] which specializes in the manipulation of codes introduced by image banks, caricatures this type of imagery in order to create new types of narrative and new stereotypes. In 2012, DIS occupied the exhibition of Katja Novitshova and Timur Si-Qin at the CCS Bard galleries for a photo session, Competing Images (2012), staging live models posing alongside the installations, the way that Internet users adulterate images by adding things to them. So the “Photoshop retouch” took place physically and eventually produced an online image like the others. It is disturbing to note that these images, be they original or artificial, are side-by-side on the same exchange platforms with no demarcation, in a context where most works of art and exhibitions are appreciated as a result of online images. This partly corroborates Artie Vierkant’s approach in his project Image Objects (2011-in progress). The origins of the works in this series are always images which, once affixed to dibond, exist physically to be hung in the exhibition venue. When the moment arrives to document the work by photographs, Vierkant alters their image on Photoshop, thus giving it a new form and a new existence. The viewer’s possible perception of it is consequently de-stabilized by a multi-facetted work, though one that is physically intact. The artist’s approach in fact does away with any hierarchy between the real work and its image, because these are henceforth grasped on an equal footing.

Sara Ludy. Extrait de / Still from Spheres 1-20, 2013. Projection numérique, disque Blu-ray / digital projection from Blu-ray disc. Dimensions variables. Courtesy Sara Ludy ; Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery, New York

Kari Altmann, for her part, appropriates the language of online consumption, marketing and technological communication thanks to compilations of images and videos brought together on her website. Her online works are intended to be perpetually evolving and are not externalized, unless somebody proposes this to her for a show. So the work changes states without its online version being affected: her work shown off-line—by way of a video monitor or a print—is always viewable online and still will be after the show. What is more, the artist does not regard her off-line presentations as “exhibitions”, but as another way of existence for her productions which are basically being continually exhibited. This relativization of the exhibition space as an end in itself came across again in “Exhibition One”, which Kari Altmann took part in, an exhibition organized by Timur Si-Qin in a white cube as a synthetic image, the Chrystal gallery, and presented simultaneously in a physical space—Gentile Apri in Berlin—and online, from 10 May to 10 June 2010. The question of knowing where the work ends and where its documentation begins was, as a result, offset by a digital work including both phenomena at once. [8]

The to-and-fro circulation of images, on and off screen, takes relevant shape in Antoine Catala’s Topologies (2010). Set up opposite each other, two plasma screens are connected by a wide tube whose ends are covered with a mirror-like surface, reflecting and distorting the images broadcast. This flow of information, endlessly moving from one screen to the other, seems like an amorphous state-of-the-art technological structure, at once fascinating and threatening.

Because of the success of online sales, consumer goods are now part and parcel of this diffusion. Yngve Holen’s installation Parasagittal Brain (2011) invites visitors to make their way between two long shelves on which are arrayed ordinary items—kettles, water purifiers, irons, etc.—which have the particular feature of being split into two so that each part is placed on either side of the passage. Their innards are thus crudely splayed, even though their presentation remains thoroughly symmetrical, and where they are cut is faultless. Altogether new, on the one hand, these objects are nevertheless inoperative, so they display their uselessness and their forthcoming replacement, which can be made with a few clicks. With Planned Fall (2013), Aude Pariset creates a disconcerting atmosphere in which presentation dummies dressed in rotting clothes seem to be on the verge of being swallowed up in garbage bags. By diverting the codes of commercial presentation, this installation throws the contemporary “prosumer’s” compulsive habits and desires off-balance. Like jars of formalin, Sean Raspet’s plexiglas cubes hold a wide variety of objects—and even digital prints—in a translucent hair gel, reminding us of the sterile atmosphere of laboratories.

If admitting that technological progress generates behavioural and morphological changes among human beings nowadays verges on being a truism, let us add that the Internet has greatly contributed to making this a generalized state of affairs. Portable computers and smartphones are now prostheses which function with us like extra organs, or rather “extensions of ourselves”, as Marshall McLuhan might have put it. We end up thinking in accordance with the way they function, and we literally become PC, Macbook or smartphone. N. Katharine Hayles points out that if the technological advances of information cannot fundamentally replace the human body, they can perfectly incorporate it, including our day-to-day habits. [9] Anne de Vries’s Timetables (2011) present a set of tables printed with cloudy skies, on which are lying ceramic hands/smartphones, conjuring up the host of different “cloud-computing”-type connections appearing and disappearing as required, activated by prostheses working like extra organs. If the hands of 21st century man are represented like this, it is helpful to see what is going on with portraits of him, and in particular those of the N.A.D. (NewAgeDemanded) series (2012-in progress) “sculpted” by Jon Rafman. Borrowing the classic form of the bust, the artist makes a series of hybrid portraits which the acceleration of present time would prevent from becoming fixed. At once virtual and real, these busts are part of “fields of displacements, changes and movements”, re-negotiating the principle of representation in an “informational environment” [10]. Social networks, blogs, Tumblr micro-blogs and Instagrams make it possible for absolutely anyone to be in a state of constant representation. Jaakko Pallasvuo points out that these sites also offer the means for constructing identities and inventing an avatar for yourself: [11] his video Reverse Engineering (2013) depicts him in different identities, talking about himself and his experience as a 21st century artist with the help of several voices and faces, filmed with a webcam. Involved here is a video posted on YouTube, akin to millions of others, thanks to which numerous users think they can have access to celebrity. But access to the artist’s “profile” is not gained because of the image, but through a discourse that is much more representative of his personality, obscured by a number of faces and images which upset web-targetting habits. Katja Novitskova also offers a good overview of the way in which egocentrism and exhibitionism match self-representational systems available online. The digital collages of the series Earth Call 1 & 2 (2012), associating landscapes found on Google Earth with selfies of young men posted on Tumblr, emphasize the self-sophistication achieved by the swift retouches and corrections made possible by technology. They illustrate what might be the “self-concern” of the 21st century. The landscape genre is likewise renewed: captivated by Second Life, video games and standard habitat imagery, Sara Ludy proposes videos in which the eye nonchalantly floats in perpetually evolving virtual landscapes. Sphere 1-20 (2013) consists in the projection of an unidentified floating object in the middle of a moving space which, each and every minute, changes and spins on itself in a new décor. Her immersive environments, which are deserted by any kind of living being, are psychological and meditative zones to be occupied.

Simon Denny TEDxVaduz redux, 2014 Installation T293, Rome Courtesy Simon Denny ; T293, Naples / Rome. Photo : Roberto Apa

Among these so-called “post-Internet” practices, many incline towards an archaeological reading of technological progress, like Aleksandra Domanovic who makes her way through the recent history of Yugoslavia, her native country, via the prism of the Internet. Titled “From Yu to Me”, her show at the Basel Kunsthalle (2012) illustrated a powerful attachment to the memory of that now vanished nation, as well as to the ensuing deregulations in matters of identity and culture. The domain .yu, formerly used for Yugoslavia, was done away with in 2010 and replaced by as many domains as there are now new nations. For the artist, this act represents the final elimination of her country within an international political context where the address of the domain now matters more than the national anthem. The series of sculptures resulting from the project The Future Was at Her Fingertips (2013), depicting prostheses of hands on tall plexiglas pedestals, draws inspiration from experiments undertaken by Rajko Tomovi, trying to give back the sense of touch to soldiers amputated during the Second World war, using an artificial intelligence procedure. Here the artist aims to reveal the significance of the pioneering work of women like Ada Lovelace, Sadie Plant and Borka Jerman Blazi in the development and creation of cybernetics, virtual reality, multimedia and the Internet. It was also a woman who was for the first time photoshopped in 1987, as we are reminded by Constant Dullaart’s project Jennifer in Paradise (2013). Depicting a topless woman on a beach at Bora Bora, enlarged then displayed on a wall by the artist (letting viewers see the grid of pixels), this photograph was taken for experimental purposes by John Knoll, co-creator of Photoshop, in order to demonstrate the efficiency of his software; the exhumation of this image reminds us of a time when it was still possible to envisage the authenticity of images.

Speculations about the future are also recurrent with these artists. In his text A Million years of Porn, Timur Si-Qin relies on the theory of sexual selection to explain how certain species change morphology on the basis of physical criteria sought during mating, such as characteristics indicating fertility and signs of resistance to parasites. Transferring this principle to the human species, the artist notes, in parallel, that, in 2006, $97.06 billion were spent worldwide on the consumption of pornography and that 25% of Internet searches have to do with this area. He concluded that human beings under the influence will in future seek out partners endowed with physical attributes similar to those of porn actors, which might contribute to the evolution of the human species, in the following ways: in 69 million years, women will have hairless bodies and generous bosoms, and men will have disproportionately large muscles and penises. [12] The updating of evolutionist theories combined with Manuel de Landa’s neo-materialist realism also give Katja Novitskova the conceptual tools required for her anthropocene-like vision of the world. The publication resulting from the project Post-Internet Survival Guide is presented as a survival guide in the face of the many different changes with which not only the human species but also the organisms constituting the Earth are currently confronted: “…The notion of a survival guide arises as an answer to a basic human need to cope with increasing complexity. In the face of death, personal attachment and confusion, one has to feel, interpret and index this ocean of signs in order to survive.” [13] Other writings by the artist remind us that the principles of attraction and repulsion, key concepts of evolutionary biology, are also clearly applicable to the sphere of art. The sight of animals has always stimulated the survival instinct of human beings, along with their affective reactions. Resulting from an autonomous evolutive process, art also produces powerful emotional reactions in man, though for different reasons. To explore this relation, Novitskova has produced a series of sculptures titled Approximation (2012-in progress), highly seductive pictures of animals affixed to billboards, designed to produce in the viewer an emotional reaction attributed to a remote atavism. She deduces from this that these pictures of animals will soon represent powerful resources, as attested to by Intensive Differences 003 (2012) , a papyrus on which is printed an image of Justin Bieber photographed beside a dolphin, to promote his brand of clothes, thereby arguing that the intensity produced on seeing these images might become a source of energy that it will be possible to make use of in the near future. [14]

Let us bear in mind that this generation of artists is evolving in a free-for-all neo-liberal economic system which, even if in crisis, always manages to stay the course. Financial power, which is not easy for States to control, is akin to a fast and elusive flux which undoubtedly explains why liquids and fluids –and their representations—are so present in works. The monetary de-materialization at work since the end of the Bretton Woods accords contributed to the making of a financial system in which currency had no more than a fictitious value. Payments by credit card and PayPal contribute to this transactional fluidity. The post-Fordist principles of the digital economy permit the de-territorialization of capital and the establishment of high-tech companies like Google, Amazon and Microsoft in tax havens, so as to dodge being taxed in countries which they profit from. The duo AIDS 3D (Daniel Keller/Nik Kosmas) is interested in these new aspects of the globalized economy: Absolute Vitality Inc. (2012) specifies unambiguously how the art market is part and parcel of this system. Akin to a platform of lectures and encounters, this installation sees itself as the promotional organ of a company purchased in 2012 by artists from a provider of services for front companies, located at Cheyenne in Wyoming (USA). Conceived as a multi-function back-up for their forthcoming projects, the main goal of this company was to use a multi-layered strategy of diversified growth, enabling collectors to invest in works of art at minimum risk, with maximum return on investment. What is more, artists have put forward the idea of devising works based on the data-mining used by marketing agencies to target potential consumers: “we’ll use a program like Lexalytics to do semantic analysis on a database of art writing in order to create “meaningful” descriptions of artworks. Then we’ll work with someone to write algorithms that, based on those descriptions, create instructions for new artworks. And then finally we’ll exhibit the works and analyze the audiences opinion and behavior.” [15] Let us note that, in an interview with Jaakko Pallusvuo and Jean Kay, they are both in agreement about the similarities existing between the inter-disciplinarity hallmarking present-day art and the capacity of late capitalism to appropriate everything for itself, even criticism of it. [16]

Creation, economics and state-of-the-art technology are incidentally involved in important encounters, like the TED (Technology, Entertainment and Design) lectures, and the more recent DLD (Digital-Life-Design), bringing together artists with start-ups and the most innovative of personalities, so as to share experiences and ideas to do with the future of our society. Simon Denny, who is concerned by the influence of technological progress on our ways of communicating, has been working since 2013 with Daniel Keller to organize a TEDx event, following the invitation extended by the Liechtenstein Kunstmuseum, in the city of Vaduz. By literally adopting the format and content of TEDx encounters, the artists designed the lecture set using communication codes employed in this kind of event. There was a succession of nine participants coming from creative, legal, economic and political spheres, each one with twelve minutes to present their innovative approaches and ideas to the public. Based on an ideological format that is much valued though criticized for its pseudo-scientific decisions, TEDx Vaduz comes across like a false parody whose purpose is the analysis of the values, aesthetics and tendencies conveyed by the technological economy.

What emerges from the above-mentioned practices is the reflection of a troubling, not to say alarming historical situation, linked to important paradigm changes, at the root of which we find the Internet and the new technologies. Faced with such facts, we might expect works with a marked critical content speaking out against the future towards which the digital culture seems to be projecting us. But this is not the direction espoused by the approaches of most of these artists, who, according to Constant Dullaart, are leaving this work to activists, and producing allegedly “post-Internet” works, while these latter are “always shown in the most hierarchic and conservative of media that the art world can offer: the white cube.” [17] But can one really stop the other? Constant Dullaart’s approach tends, incidentally, to emphasize that the Internet is no longer the “zone of temporary autonomy” [18], the medium of an alternative political culture that it was in the 1980s, nor the space of freedom much vaunted by the media, with these latter reporting, for example, that the Arab revolutions would never have been possible without Facebook… The Internet now represents the principal instrument of the “society of control” announced by Gilles Deleuze, as is shown by the NSA’s latest declarations, and the inextricable situations of Julian Assange, Chelsea Manning and Edward Snowden. So how could the Internet be more relevant than an exhibition room to react and resist? As an explicitly politically committed artist, Zach Blas does not seem to ask himself the question. His project Facial Weaponization Suite (2011-in progress) reacts to the spread and trivialization of biometric and facial recognition procedures. It consists of a series of masks designed using facial data of different subjects, unfathomable by biometric reading systems. Among these masks, the Fag Face Mask (2012), made using facial data of homosexuals, tends to withstand recent scientific studies, postulating that it is possible to determine the sexual orientations of the subjects using biometrics. Worn at large social gatherings and performances, these masks are conceived as opaque props of collective transformation, contesting the predominant forms of political representation. The white cube and the Internet are nevertheless still just as viable means of strategic dissemination for the artist. This plurality of methods of presentation in no way alters the relevance of the critical scope of his involvement. It would therefore be wrong to underestimate the political consciousness of this generation and reduce its work to a cold duplication of Internet imagery in commercial galleries. For these practices can possibly shed light for us on a certain shift of the political struggle, which is no longer imagined the way we think. Perhaps they have found a way of “achieving the organ-less body, without untrammelled de-stratification”. [19] In this case, we should see therein, in parallel, postures henceforth situated at another conceptual level than those hackneyed postures of traditional activism.

- ↑ Josephine Berry-Slater rehabilitated the notion of site-specificity to describe the experiments of Net.art artists at the Post-Net Aesthetics conference which was held in October 2013 at Londoon’s ICA.

- ↑ Joshua Simon, Neomaterialism, Sternberg Press, Berlin, 2013, p. 17.

- ↑ “Interview with Marisa Olson”, We Make Money Not Art, 28 March 2008.

- ↑ Post-Internet Survival Guide, edited by Katja Novitskova, Revolver Publishing, Berlin, 2011.

- ↑ Artie Vierkant, The Image-Object Post-Internet, 2010.

- ↑ Careers are last season: An interview with Jaakko Pallasvuo, by Tim Gentles, p. 62.

- ↑ disimages

- ↑ Chrystal Gallery

- ↑ N. Katherine Hayles, How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature and Informatics, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1999.

- ↑ Tiziana Terranova, Network Culture : Politics for the Information Age, Pluto Press, New York, 2004, p. 7, quoted by Ceci Moss in « Expanded Internet Art and the Informational Milieu » which appeared on the website RHIZOME, December 2013.

- ↑ « An interview with Jaakko Pallasvuo » on aqnb, 31 May 2013.

- ↑ Timur Si-Qin, « A Million Years of Porn » in The future will be… China: impromptu thoughts on what’s to Come, Pinacoteca Agnelli, Turin and UCCA, Beijing, 2012.

- ↑ Post-Internet Survival Guide, op. cit., p. 4.

- ↑ On this see Katja Novitskova’s oral intervention during the TEDx Vaduz encounter organized by Simon Denny and Daniel Keller at the Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein, 7 December 2013.

- ↑ « KELLER/KOSMAS (AIDS-3D) interview by Simon Denny », in KALEIDOSCOPE/Web Specials, 2012.

- ↑ « An interview with Jaakko Pallasvuo » on aqnb, cf. supra.

- ↑ « Beginnings + Ends », Frieze, n° 159, November-December 2013, p. 127.

- ↑ Hakim Bey, The Temporary Autonomous Zone : Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism, Ed. Autonomedia, New York, 1991.

- ↑ Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

- Partage : ,

- Du même auteur : Everybody in the place. La culture club comme antidote à l'institution d'art contemporain ?, Protective Body, Post Human,

articles liés

Du blanc sur la carte

par Guillaume Gesvret

« Toucher l’insensé »

par Juliette Belleret

Une exploration des acquisitions récentes du Cnap

par Vanessa Morisset