Xabier Arakistain

Why not Judy Chicago, after all?*

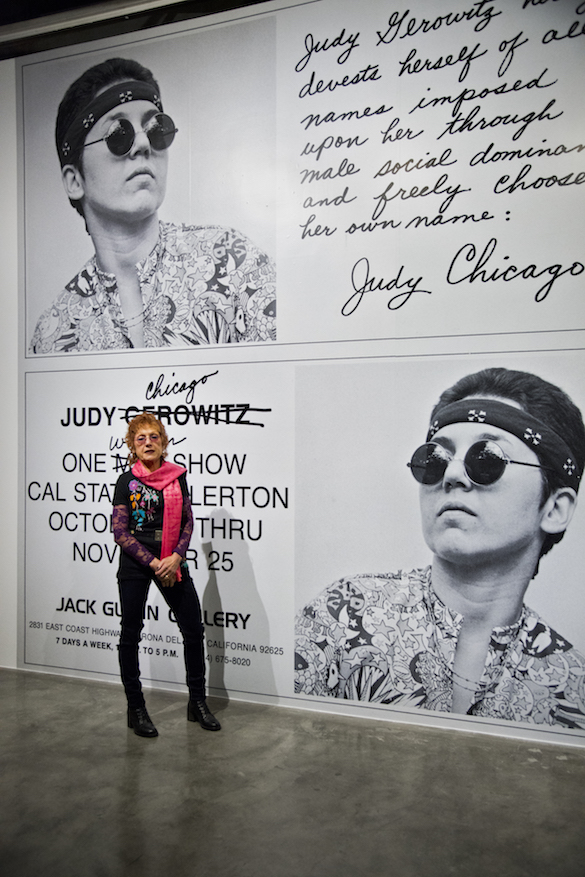

The CAPC in Bordeaux is organizing the first institutional exhibition to be held in France of the work of Judy Chicago, that oh-so-influential figure of feminist art and, we might also say, of American art. Hers is an essential œuvre which challenges the very foundations of the history of art as an active product of male domination, inventing, as it does, a vocabulary of forms which works against the structures of the predominant visual discourse, whose bases it undermines. So yes, why not Judy Chicago, after all? Why not a woman? And why not Judy Chicago in the museum, that historical temple of phallocentrism? These are the questions raised by the CAPC and more specifically by Arakis (Xabier Arakistain), the show’s curator, who takes up two notions which underpin the artist’s œuvre: deficit (of visibility) and disobedience (with regard to the canons). And it is no surprise that this proposition comes in two ways from a peripheral gaze: on the one hand, from an institution which, through its history and its geographical situation, stands apart from the major hegemonic institutions, and, on the other hand, from a Bilbao-based curator who defines himself above all as a feminist.

The exhibition is two-themed. The first documents Judy Chicago’s involvement in teaching, with, in particular, the significant Fresno Feminist Art Programme which she set up for women artists when she was a guest teacher at California State University in 1970, and which would be subsequently accessible for men. Also documented is the famous Womanhouse which Judy Chicago created in 1971 in an uninhabited house near the CalArts campus, as part of her teaching programme there.

The second proposes a reading of her work by way of the different periods of her career. The exhibition is a striking one because of the conspicuous presence of reproductions presented on an equal footing with original works; documents and archives are treated just like the works, one such being the artist’s major piece, The Dinner Party. This latter, which, as it were, invites female extras, supporting roles and other figures usually forgotten by History with a capital H to a women’s banquet, raises the issue of the writing of history as a tool of male domination. The use of ceramic dishes showing vulva-like forms helps us to question both the history and the visual and technical vocabulary of this domination. Just a few dishes are shown in display cases, and the whole piece is described in the form of archives and posters. Her other series, especially her Power Play paintings, are partly shown as reproductions, and this exhibition thus raises questions about what makes a work, what makes an exhibition, and the role of the exhibition in relation to the work. We discuss all this with Arakis.

Why Judy Chicago?

Judy Chicago is a 77-year-old artist whom I regard as one of the most important of the 20th century. She has just received lots of tributes in the United States, in universities and art centres, but there still hasn’t been any major show devoted to her work at MoMA, or the Whitney, or other important institutions. So “Why not Judy Chicago?” poses this very question: why not her? Why not a woman, who’s a feminist as well, whose whole work is based on questioning the canons of phallocentrism?

Why Bordeaux?

Personally, I love working on this scale, and in a dimension such as the CAPC’s. Here we’re on the outskirts, so to speak, and I really like showing things which are well-removed from the alpha and omega of hegemonic institutions.

Does the fact that the exhibition is being held in Bordeaux and not in Paris make more sense?

I don’t think it makes more sense, I simply realize that this project is only possible in this type of venue. I think Judy Chicago having a show at MoMA would totally make sense too. Why not?

Judy Gerowitz became Judy Chicago in 1971. The first part of her œuvre, produced in the 1960s, which we might describe as minimalist, seems to be under-represented. Is this because she was not yet Judy Chicago?

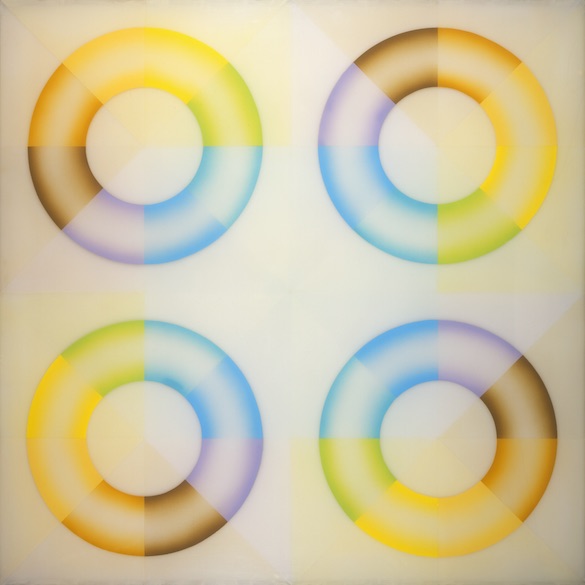

Not at all. That’s a period of her work that I like a lot, because it’s filled with lots of energy, and my viewpoint, as curator, does not involve minimizing it: the exhibition starts in 1964 with Mother Superette, and carries on with the 1969 series of Pasadena Lifesavers, her sort of minimalist paintings, and there are plenty of them in the show.

Judy Chicago, Mother Superette, 1963. Acrylic on paper, 49.5 × 66 cm. © Judy Chicago.

Photo © Donald Woodman

But aren’t some major pieces missing, in particular large minimalist-inspired sculptures like Rainbow Pickett, which belongs to the Brooklyn Art Museum, and her Bronze Domes?

All exhibitions are subject to various series of decisions. Here it wasn’t a matter of organizing a retrospective. Such an undertaking for an artist like Judy Chicago would be extremely costly, because a lot of her pieces are in the United States. My goal is to present a visual narrative of her career, based on a choice of ingredients: she has produced a very large number of pieces, and my curatorial approach consists in selecting lines of her work which illustrate her major contribution to art history.

Judy Chicago, Pasadena Lifesavers Yellow Series #2, 1969-70, 152.4 × 152.4 cm. Photo © Donald Woodman

Why have you decided to show a lot of reproductions of her works? Does the presentation of original works and reproductions on an equal footing result from a queer approach to curating?

No, not queer, rather, feminist! Judy Chicago created that fantastic imagery of the female sex which gave rise to ‘cunt art’, and this is what I discuss with her; the curatorial decisions were made in this spirit. There were two venues which were involved in this project [the Azkuna Centre in Bilbao and the CAPC both collaborated on this project], with a very attractive budget for a contemporary art show, and I acted on the basis of these data. What’s more, it seemed interesting to me to present an American artist in Europe while at the same time distancing the mystification of the art object, about which her friend, the American critic Lucy Lippard wrote brilliantly in the 1970s. So the use of reproductions didn’t seem problematic for Judy and me; the nub is the narrative that’s produced around the œuvre. Through this introduction of narrative, the visitor can gauge the way the artist’s colourful palette develops, along with her graphic style, and the way she has invented her own style, and, in the end of the day, her significance.

In a way, you’re challenging the institutional approach to art in terms of the power associated with having the original?

Precisely.

Coming to Judy Chicago’s work, I’ve had the feeling while looking at some of her pieces—and in particular the paintings which I’d describe as ‘Michelangelo-like’ in the Power Play series—that she reproduces rather than deconstructs male strategies.

No, I don’t think so. Judy Chicago is a feminist artist. What does this mean? There are two answers here. The first has to do with masculinity as representation. As a feminist, Judy Chicago does not think that gender comes down to women. Gender is men and women. Sex is male and female, there’s a binary principle. Judy Chicago produced that Power Play series in the mid-1980s based on a counter-construct of masculinity, because she had quickly realized that with ‘gender studies’, gender came down to woman. Sex is not the equivalent of woman, and she deconstructed that operation. She introduced plenty of wit into her deconstruction of masculinity. Look at her palette, sky-blue combined with pink. “Let’s feminize! Let’s create problems!”, she told us.

In other respects, as an artist, she works on art history. When she went to Italy she saw with her very own eyes the so-called Renaissance masters. In her turn, she focused on the issue of techniques and in particular those which were not often represented in the male fine arts: Indian ink painting, textiles. At the same time as she produced the large Power Play paintings, she started her series with textiles, titled The Birth Project, which depicts gestation and childbirth. Likewise, in many of her ensuing works, in the Human Rights and Holocaust series, she combined textiles with paint. That’s a feminist dimension of her art.

What do you think of the critics who consider that Judy Chicago speaks from the perspective of a heterosexual woman?

If you’re asking me about certain lesbians who criticize Judy Chicago, this, for me, is tantamount to saying that Margaret Thatcher criticized Judy Chicago. Being a lesbian or being a woman is not the same thing as being a feminist. Being lesbian is a sexual orientation; being feminist is a political option. You can’t understand masculinity without femininity and vice versa. I haven’t shown the pieces portraying homosexual motifs, perhaps I should have done, but I couldn’t show everything. My preference has been for research into the cunt as a socially constructed sign. I wanted to concentrate on the definition of phallocentrism which comes to the fore through her work on the cunt and the way in which history is constructed as an echo of a heterosexual male voice. The Dinner Party, which is one of her most important works, is a huge historical archive. History is the system which reproduces sexism and influences upbringing. Feminism doesn’t deal with the issue of women, but rather with power relations between men and women. Masculinity doesn’t exist, femininity doesn’t exist. These are concepts that have been socially constructed in a certain historical period. But they are constructed in a binary way. In this sense, Judy Chicago’s use of femininity is highly political. Phallocentrism is socially constructed, even if it seems natural, and even if we may think that things have always been this way. When something is becoming natural one forgets that it’s been constructed. In this spirit, when Judy Chicago disseminates her coloured smoke, and places her butterflies and other symbols in the landscape, the imagery of the cunt defines the phallus, and says that it doesn’t want to be oppressed. The feminine is used against the masculine, and it’s important to deconstruct the power plays at work between the feminine and the masculine. By positing the cunt, she is saying that the phallus is constructed. We’re running counter to Freud and Lacan, with Freud asserting penis envy as a feminine determinant and Lacan talking about the formation of subjectivity in front of the mirror in an initial stage. Judy Chicago says: “I’m not envious of the penis and, as a little girl in front of the mirror, I don’t see the absence of phallus but the presence of cunt”. Which is tantamount to saying: “I don’t accept the law of the phallus”.

In terms of curating, this exhibition crucially raises the issue of the viewpoint, and prompts to question the viewpoint from which you are expressing yourself.

I’m a feminist and I adopt a feminist viewpoint. From the outset, as part of my studies, feminism helped me to find a whole lot of answers about society, and about my own life. So when I became a curator, I was already a feminist. Throughout my career as a curator, I’ve worked in the field of art from a feminist perspective, testing and applying feminist strategies. I regard myself as a political activist, but it’s important to make a difference between activism and art. Over the last few years, I’ve been horrified by this wave of “aRtivism”. I think it’s as bad for activism as it is for art, and I don’t want to have anything to do with it.

But as a curator, do you see yourself as an activist? Are they two different things, or are they overlaid on each other?

Absolutely. Society is divided by sexual differences, and sexual differences establish a plan of specific power relations. If you’re aware of this situation, and if you’re in a position to fight against these power relations, then you’re an activist. In my case, because I wear make-up and wigs, people might say I pose a problem from a hegemonic viewpoint of sex, sexuality and gender. I’m thoroughly aware of the fact that I pose a problem.

Do you define yourself as queer, transgender…?

I define myself as a person and as a feminist.

« Why Not Judy Chicago ? » CAPC, musée d’Art contemporain de Bordeaux, 2016. Photo : Frédéric Deval.

* Why not Judy Chicago?, CAPC, Bordeaux, 10.03_4.09.2016.

Related articles

Céline Poulin

by Andréanne Béguin

Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Interview with Warren Neidich

by Yves Citton