Anthropocenia

Because the Anthropocene—the age in which we are more than ever the heroes (understand by that that man is now master of the planet down to its essence)—is a concept that is still open-ended, at least until 2016, the year during which the experts of the International Geological Congress will meet, it is fanning argument, speculation and fantasy, not only among scientists but also among a cohort of thinkers including the philosopher Bruno Latour, one of its most brilliant devotees and apologists. “What makes the Anthropocene a clearly detectable landmark well beyond the boundary of stratigraphy, is the fact that it is the most relevant philosophical, religious, anthropological and […] political concept for sidestepping the notions of ‘Modern’ and ‘modernities’”, he writes.1 His latest project to date, Le théâtre des négociations2 occurred in late May 2015, at the Nanterre-Amandiers Theatre, in advance of the COP 21 [the Conference of the Parties under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change to be held in Paris in December] and performed by more than 200 students from all over the world, gravitating around a nucleus hailing from the Sciences Po, as parent company, and the SPEAP master created by Latour, bringing together artists and researchers from different fields. Because the Anthropocene is a living matter in the process of being shaped and defined, but which has not yet produced any consensus, it is whetting appetites. After asking the Sciences Po students, in 2011, to take up all the exchanges of the fruitless 2009 Copenhagen Summit (La négociation. Qui veux sauver le climat?), Professor Latour thus invited tomorrow’s leaders to work on tomorrow’s COP. An original process? The assembly, smacking of the UN (with its representatives of the 195 nations) also has to negotiate with the elements (water, forests, oceans, atmosphere, intact oil reserves, etc.), and with communities which do not usually have a voice at the table, like indigenous peoples. What is more, the apparently more classic delegations, like those of France, encompass at times antagonistic camps, because taking part in them are representatives from Polynesia, Areva [France’s leading nuclear energy company, Trans.], the Paris City, and the NGO Action Climat. Clash guaranteed! During a speculative marathon lasting three days and two sleepless nights, the members proceeded to make alliances, some of them withdrew, and the whole thing was followed on a web platform, involving the visualization and shaping of power plays, alliances and illicit dealings.3

Charles Stankievech, LOVELAND. Installation with HD video.

In this video, the artist defuses grenades in an Arctic landscape until the space is saturated with an emerald colour, a paranoid vision fuelled by sci-fi and a fascination with these strategic spaces, be it on a military or energy level.

In the end, the students of the class of 2014-2015, Bruno Latour, Laurence Tubiana (French ambassadress for international climate negotiations) and Frédérique Aït-Touati (director and researcher) came up with a physical platform accessible to the citizen-cum-visitor, and this is precisely where the formula definitely worked less well because of a definitional absence of that “famous” spectator. Access to the negotiations took place in a spectacular manner, from a rostrum, a little at a time and over a short period of time, leaving no possibility of picking up and understanding anything at all, with the visitor thus remaining reliant on spokespersons regularly describing the state of progress of the discussions in the circulation spaces. Lecture theatre with strict projection schedules, a moveable video library by Fabrice Gigy (1998, FRAC Ile de France), a glowing globe in a smoke-filled room, (a somewhat forced recourse to symbolism), a room for relaxation furnished with deck chairs around a quadrilateral pool of black water, navigable with an available inflatable boat, open areas and others prohibited for mere mortals, what was one to do in this theatre of negotiations with ambivalent access? A wait-and-see spectator rather than a citizen, this is the role assigned by the experiment to some 1,300 curious attendees for those three days, sad reality of the absence of peoples in all these exchanges, and our absolute uselessness in the heart of this tractatus politicus. As in most ecological art and affiliated praxes, there are not nearly enough questions raised about the status of the spectator, his activity within the arrangement which might be more productive than that of the simple onlooker, and his role as citizen, voter, disillusioned cynic stripped of any kind of margin of manoeuvre. He is only barely recognized in the not very enviable role of person in charge, not to say culprit. But over and above this downside, Le théâtre des négociations represents a powerful marker of the extraordinary stuff of the Anthropocene in the eyes of artists. Armin Linke documents all the trappings within the Anthropocene Observatory, associated with Anselm Franke as well as the architects Palmesino and Rönnskog (Linke in particular photographs rooms in Natural History Museums, places that challenge the whole schemes of our representations of Nature); the Canadian artist Charles Stankiewecz organizes lectures and introduces the notion of a visual line of thinking about forms of fossil energy in a, for the moment, literary production, having produced paranoid landscape video works.

The latest researches often have recourse to photography and video because, for want of creating any consensus, the Anthropocene has to adopt an image. This raw matter in fact remains elusive, because the specialists have not yet decided if it began 50,000 years ago with the first hunters, 5,000 years ago with the domestication and cultivation of rice in Asia, in 1784 with Watt’s invention of the steam engine (marking the advent of the age of coal and fossil fuels), or the 16th of July 1950, with the explosion of the first hydrogen bomb, unless it was in the 1950s with the plastic essence of the “Great Acceleration”, both consumerist and productivist, the plasticocene. The Anthropocene is still a perfect utopia, the stuff of ideal speculation. Defining its representation a posteriori is just as novel; from an investigation at the heart of images of the past to the quest for its trace to the invention of a hitherto thoroughly unknown aesthetics, everything is possible. And if the Anthropocene is also exciting, this is because it upsets our whole plan to protect nature, whose development was understood, up until now, as being separate from our sphere, with a nature requiring protection fuelling philosophical and ethical debate about the recognition of its intrinsic qualities. “No postmodern philosopher, no anthropologist, no liberal theologian and no political thinker would have dared to situate the influence of human beings on the same scale as rivers, floods, erosion and biochemistry. What “social constructivism”, determined to show that scientific facts, social relations and inequalities between the sexes are “merely” historical episodes manufactured by people, would have dared to say that the same thing can also be said about the chemical composition of the atmosphere?”4

Ursula Biemann, Deep Weather, 2013. 9 min. Film still. Deep Weather comprises ‘Carbon Geologies’, set in the tar sands of the boreal forests of Northern Canada, and ‘Hydro Geographies’, set in the near-permanently flood-threatened Bangladesh. The connection is pursued through two narratives, one about oil, the other about water – vital ‘ur-liquids’ that form the undercurrents of all narrations as they are activating profound changes in the planetary ecology

Ursula Biemann, Deep Weather, 2013. 9 min. Film still. View of areas where Alberta’s tar sands are being extracted, a destructive activity for the northern forests all around and one of the most polluting kinds of petroleum in the world.

The originality of this geological era is that it is shaping the future. Geologists usually define eras well after they are over. The Anthropocene is happening now, and it is determining the future. This is terrain which makes it possible to imagine a geography, landscapes, a climate, and diseases—in a nutshell a whole speculative arsenal which is the selfsame one which seems to be missing in artists, when ecology and environment are involved. What precisely are these practices which run the risk of ushering in a future potentially bottle-fed in the manner of the latest Naomi Klein book,5 to read which is a morbid but primordial delight? For the time being, the various forms are vague. For Klein’s implicit apostles, The Natural History Museum, a multi-facetted group arising out of the Not An Alternative Brooklyn artist’s collective which has been working for ten years on influencing the mechanisms of popular understanding, with the aim of giving rise to social and political changes, the practices in question use the grammar and logic of the most classic form of activism. These artists and researchers from several different backgrounds are kicking up a fuss in museums by demanding the resignation of David Koch from his job as a member of the advisory board of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, in Washington DC, and as an influential patron of the American Natural History Museum, in New York (kickkochofftheboard.com). Where lies the problem? He is a shrewd customer. Koch is sitting on the seventh largest fortune in the world (2013) and, it goes without saying a Republican. He owns Koch Industries, working merrily into oil, gas, the chemical industry, asphalt, fertilizers, plastic production, and so on. Whence an unfortunate tendency to be extremely active in the programming of the museums he contributes to. So an exhibition about climate change will see the dangers and causes of this phenomenon considerably re-examined under the pressure from petrodollars.

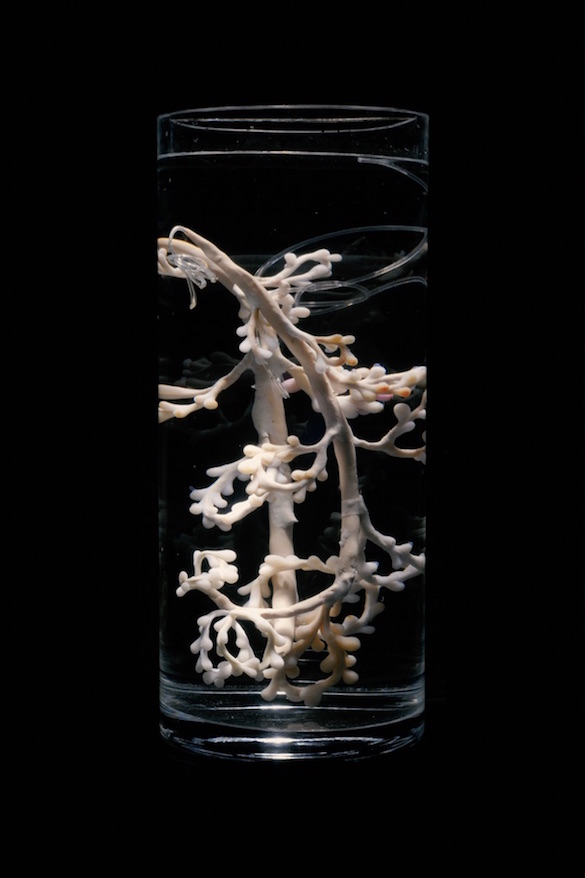

The Natural History Museum. One of the vats holds the water from a New York fountain, while the second contains water from the Alaskan North pole region, contaminated by chemical products released from a Koch industries refinery.

The Natural History Museum (NHM) began its campaign at the Queens Museum in September 2014 by holding a three-day symposium at which artists like Mark Dion, Hans Haacke and the young Canadian Steve Lyons spoke about, among other things, the unwholesome funding of museums and their influence in both the representation of nature and environmental issues. Then in Atlanta, on the 29th of April 2015, at the largest convention of the American Alliance of Museums with more than 7,000 professional attendees from sixty countries, the NHM showed dioramas identical to those on view in New York. With the difference that in their diorama Koch’s sickening imprint was presented in a display window in which the polar bear was portrayed on a section of pipeline produced by Koch, and included a comparison of water samples made in New York and off the coast of the Koch refinery in Alaska. The demonstration put paid to all Koch’s outrageously reassuring communications about the harmlessness of his installations in fragile environments. Added to this was a programme of promotional films produced by the major oil companies (BP, Shell, Chevron, and the like…) awash in holier-than-thou vows and adulterated promises, in a cycle titled “Coal is good for you. Dirty videos by the fossil fuel industry”.

In October of this year, the Natural History Museum will stage another exhibition for the audience of museum decision-makers participating in the conference of the association of Science and Technology Centers in Montreal, before proceeding to Paris just when the COP21 Climate Change Conference is being held. All these actions, combined with especially sensitive field visits (a lake coveted by the gas industry, for example) and aggressive statements published in organs like The Guardian,6 are fuelling a method of action which uses known strategies, but is based on stakes and challenges that are nothing if not topical. In a more speculative vein, the very recent book Art in the Anthropocene. Encounters Among Aesthetics, Politics, Environments and Epistemologies, edited by the academics Etienne Turpin and Heather Davis,7 offers an important and thrilling overview of full-scale thinking about the potential of the Anthropocene, with contributions from Bruno Latour, Donna Haraway, and Peter Sloterdijk, no less, and a plethora of contributors including the recognizable names of Vincent Normand, Fabien Giraud and Ida Soulard, representing the French-speaking world. In it, these latter present Marfa Stratum, a polymorphic project (including sculpted forms, texts and lectures) started in 2013 from the Texan residency, based on which a geological fiction set in the Chihuahua desert was imagined. Ilana Halperin informs her imagination with crystal structures and rock formations, in order to give material form to a relation to geological time in sculptures. Pinar Yoldas reflects on a new life in the Plastisphere (An Ecosystem of Excess), giving rise to new hybrid species and a taxonomy that renews the Linnaean table of species. Except for these examples, the artists involved are still attached to the virtues of the documentary. So Ursula Biemann of the World of Matter collective (whose web platform is an especially successful example demonstrating the complex structures which link ecology, economics and politics using tentacular investigative films) produces particularly thorough works dealing with the interrelation between global and local, in the wake of the repercussions of decisions made thousands of miles from a site. So in one and the same work her camera focuses in on tar sand operations from Alberta in Canada to Bangladesh, among peoples struggling in a derisory way against rising water levels (Deep Weather, 2013). Despite these examples, some texts further underscore the fact that the Anthropocene has no imagery, and no clear representation. “The image of the Anthropocene is still to come. The Anthropocene is the ‘Age of Man’ that announces its own extinction. In other words, the Anthropocene thesis posits the human as the end of its own destiny. […] In short, images of the Anthropocene are missing ; thus, it is first necessary to transcend our incapacity to imagine an alternative or something better by drawing a distinction between image and imagery, or pictures”.8 What is being played out with the Anthropocene is a change of thinking. Thinking about “us”, from now on man’s relation to nature, no longer has to do with the speculation of a small group of environmentalists. Thinking about the future is becoming intrinsic to the definition of our geological past. The time lines are forever overlapping. And in a discourse on climate change which demands that citizens and states alike start thinking now about a state of the earth which will only be realized in fifty years, while conceptualizing the beginning of a geological era, the challenge is nothing if not pregnant. And last of all, whatever scientists decide, whether the Anthropocene was in the end just a sub-section of the Holocene, or whether, when all is said and done, it is not an official era, it has become the most fertile arena of thought imagined since postmodernism.

Pinar Yoldas, Ecosystems of Excess : Stomaximus Plastivore Digestive Organ, 2015.

The artist extrapolates a stomach capable of digesting and metabolizing all kinds of plastic by-products, an angst-inducing kind of “progress”.

1 Bruno Latour, “L’Anthropocène et la destruction de l’image du globe”, in Emilie Hache (ed.), De l’univers clos au monde infini, Bellevaux, Editions Dehors, 2014, p. 32.

2 MAKE IT WORK / Le Théâtre des négociations, a Sciences Po and Nanterre-Amandiers project, 29, 30 and 31 May 2015. http://www.nanterre-amandiers.com/2014-2015/make-it-work-le-theatre-des-negociations/

3 The students reached one or two generally agreed conclusions, part agreements and proposals, including the creation of a climate refugee status, and the recognition of ecocide as a crime against humanity. Over and above these principles, the best progress involves keeping records of imported greenhouse gases, meaning the gases caused by production of onsumer goods outside the country where they are consumed.

4 Latour, op.cit., p. 33.

5 Naomi Klein, This Changes Everything, Capitalism vs. the Climate, 2014, Simon & Schuster.

6 Steve Lyons and Beka Economopoulos, “Museums must take a stand and cut ties to fossil fuels”, The Guardian, 7 May 2015 : http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/may/07/museums-must-take-a-stand-and-cut-ties-to-fossil-fuels

7 Heather Davis and Etienne Turpin (eds.), Art in the Anthropocene, Encounters Among Aesthetics, Politics, Environments and Epistemologies, London, Open Humanities Press, 2015. As a speciality of this publishing house, books can be read free of charge in pdf format : http://openhumanitiespress.org/art-in-the-anthropocene.html

8 Irmgard Emmelheinz, “Images do not show : the Desire to See in the Anthropocene”, in Turpin & David (eds.), Art in the Anthropocene, op.cit., p. 138.

(Image on top: The Natural History Museum, remake of a diorama about climate change on view at the Natural History Museum in New York in 2009. A section of a Koch Industries pipeline (owned by David H. Koch, member of the museum’s board of directors) has been added. http://thenaturalhistory museum.org)

Related articles

The World Through AI

by Warren Neidich

Paris noir

by Salomé Schlappi

Some white on the map

by Guillaume Gesvret