Taryn Simon

Long regarded as a neutral recording technique, a kind of automatic stand-in for reality, photography is thereby endowed with not inconsiderable responsibilities in the composition of discourses about power and authority. Taryn Simon, who focuses her work on these issues, questions the use made of photography in important legal and police institutions. Photography can in fact become a medium of revelation when associated with words, it leaves the field open for narrative, turning the authority discourse back on itself. By way of large projects which all function a bit on the same model—introduction of restrictive work procedures giving rise to productions in series—the New York artist casts an uncompromising eye on the world, an unlikely and unfettered sampling which composes its time capsules by making negative portraits of this Babel in perpetual motion that we live in. In the apparent guise of Pérec-like inventories, her accumulations redeploy the image with a new system which gives viewers more latitude to compose their own perceptible paths in the midst of chaos: the artist thus helps to set up a new hermeneutics, at a time when the image is turning out to be the major tool when it comes to communicating and acquiring knowledge.

The Aesthetics of Absence

The Louis Vuitton Foundation recently provided Taryn Simon with a dream ballpark: at the inauguration of the building in the south of Paris, the artists were commissioned to take as their subject the execution of this pharaonic work. Frank Gehry’s project is part of a new wave of buildings conceived by renowned architects and designed to accommodate major programmes. This, in itself, raises issues about the deep-seated motivations of contemporary art “patrons”, over and above the demonstration of a spirit of disinterestedness and impartiality, and the desire to give back to metropolises like Paris the influence and lustre which they are said to have lost. As it happens, the architectural star system corresponds perfectly to the star system of contemporary art, from which outsiders only rarely emerge.1 On the face of it, this kind of debate does not seem to be the number one concern of an artist who, once she agrees to take part in such an event, seems, de facto, to cling to a certain kind of contemporary art function… But only on the face of it, because the modus operandi that she has opted for can also be interpreted as a deconstruction of a system which pertains broadly to the promotional designs of the brand and which, as such, is also part and parcel of a praxis which de-dramatizes and neutralizes the affects and the political and societal challenges supposed to inform the praxis of contemporary art. The distinctive feature of a “modern” construction site of great scope, in addition to introducing innovative technologies and techniques—as the designers have not shrunk from doing by highlighting the technical prowess represented by the cantilevered development of the “wings” of the foundation—, is to group together workers hailing from the most diverse of ethnic backgrounds: it is a commonplace to say that most construction sites in western cities are manned by foreign workers, usually from countries in the South, from Portugal to North Africa, by way of Turkey and Cameroon. Any large construction project encompasses a workforce that is geographically heterogeneous, but rather homogeneous with regard to its conditions of subsistence, belonging as it does to the poor fringe of a globalized population, which, without beating about the bush, expresses its beliefs and its preferences, its likings and its aversions, by way of an expressive force which stands in sharp contrast to the urbane solicitude of the contemporary art public.

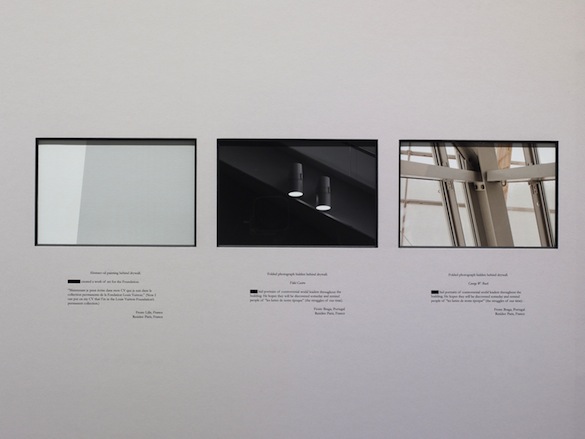

Taryn Simon, A Polite Fiction, 2014.© Fondation Louis Vuitton. Photo: Marc Domage.

In A Polite Fiction, we find all the ingredients of the “Simonian” system: an immersion which makes it possible to identify the major situational factors, the establishment of human relations essential for the production of a localized mythology and, stemming from this immersion, an initial series of photographic works, framed and presented in accordance with a repetitive procedure in which the caption describing the object photographed by the artist is followed by the author’s commentary on the “work”: what is invariably involved is texts, graffiti and drawings, which have been buried beneath the successive coats of paint of the new building. The ghostlike presence of these “works” which the artist brings forth can be read as an ironical response to the neutrality of the white cube. It can also be taken as the intrusion within a cosseted world of that ancient third world made up of migrant workers whose cultural references appear to be decidedly at odds with the politically correctness conveyed within contemporary art. But the most important thing is the fact that the procedure introduced by Taryn Simon is egregiously destabilizing in its reception, because what is presented is simply images of the walls, columns, stairways, metal frames and countless places where these “ephemeral artworks” have been hidden, it being possible to imagine and re-create them in the spectator’s consciousness only by way of the laconic wording of the caption, backed up by the “author’s” commentary, like two complementary versions, one scientific, cold and suitable for museums, the other lived in, living, and to do with testimony. What emerges from this is a new vision of the Vuitton Foundation which, conceived as a showcase for the big names in the international art scene, houses a phantom and spontaneous collection, the work of anonymous but quite enthusiastic artists, informed by a certain fondness for fantasy, wit and poetry, as is attested to by the large number of quotations of the great poets of Islam—a kind of collection that is not costly, and doubles the official one…

Taryn Simon, A Polite Fiction, 2014.© Fondation Louis Vuitton Photo: Marc Domage.

Deconstructive Machines

In most of Taryn Simon’s projects, be it Contraband, Birds of the West Indies or The Picture Collection, this is how she goes about things: she sets up an investigative procedure which enables her to produce photographs which she connects with a graphic and textual output. A whole host of intentions come into her praxis, one of the least of which is definitely not to tackle photography like the guarantee of an objectivity associated with her relation to reality. To be sure, Simon is neither the only person nor the first person to grapple with this fantasized objectivity of photography by emphasizing its ability to cover things up, but, as we have just seen with A Polite Fiction, the way in which she gets to grips with this objectivity is decidedly original: she does not force her spectators to take up a stance or bestir their consciousness, the way critical postures managed to do in the past, turning photography into a “prosecutorial” or accusatory medium that exercises the spectator’s passiveness, but rather puts photography in a position of dependence with the text. A Polite Fiction simply shows that the photo does not show anything: it is the caption (laconic and mysterious) and the excerpt of the text provided by the anonymous artists which show something, illustrating that the photographic work only exists through the situational discourse that frames it, and the narrative that widens its field of action.2

Birds of the West Indies (2013) is an impressive series of photos of the gadgets which litter Bond movies. There is no point in going back over the truly fantastic aspect of these objects which are part and parcel of the legend of James Bond, agent 007, and which, furthermore, issue from a phantasmagorical vision of the world, and from an exaggeration of the seductive nature of merchandise associated with the allpowerfulness of the west. Bringing together these objects, taken out of their film context, in an isolated series gives the sensation of a suspended, magical world, which might in a way be likened to the world of video games. At the heart of the accumulation of objects, the artist has slipped in the portraits of former actresses in those films who agreed to work with her, all posing in front of the same white backdrop which makes their silhouette stand out, and makes them float in space, but also isolates them in a suspended time-frame. The artist straightforwardly executes a brutal levelling operation which puts these latter on the same level as the secret agent’s props. So a simple juxtaposition of images is more effective than lengthy feminist arguments. This levelling of the image of woman is not merely provocative, it also makes it possible to record the power of the flattening of the photograph which, in this precise case, is capable of serving a discourse but also of checking its real impact: the reaction of the actresses approached to take part in this audition says a whole lot about the degree of alienation of these former idols. The only women who agreed to pose are those who, prior to their appearance in the Bond saga, had already developed an autonomous activity and a career in other fields, such as Halle Berry, Grace Jones and Sophie Marceau, whereas those who had been “revealed” in the cinema as Bond girls did not follow up the artist’s requests. Actresses like Ursula Andress have remained frozen in a borrowed identity, refusing to assume their lot as “mere mortals”, as Daniel Baumann aptly writes: “Making time visible is the price to be paid for not being just an element in a film like a weapon or a cat, and while some of the women who refused to be portrayed may hope to remain ageless, those who allowed themselves to be photographed distance themselves from the Bond formula, and thus from the status of accessory”.3

Taryn Simon,The Innocents, 2002. Courtesy Taryn Simon © Taryn Simon

Birds of the West Indies, like Contraband, Innocents and A Polite Fiction, is aimed at shedding light on the mechanisms at work, in a more or less intentional way, within large institutions, be they representing justice, customs and excise, the police, film, or art. The role of photography is challenged through the objectivity that is meant to define it and, in particular, in the constitution of proof within the investigation, keystone of the judicial and police system. So in Innocents, it is its character of being beyond suspicion that is cast into doubt. The anecdote of that Black American, Frederick Daye, accused of having committed a murder, whom the jury, made up of entirely of Whites and destabilized by the police’s techniques of persuasion, associated with the manipulations of the image, ends up finding guilty, shows that over and above supposed photographic objectivity, there are ideological presuppositions which steer the direction of the research and have an effect on the result of the inquiries, explaining the significance of the number of these wrongly accused innocent people. The Innocents project can be seen as an attempt to re-write countless dramatic stories which have deeply affected the lives of wrongly accused people, based on misuses of photography. Simon has made them pose again in alibi situations, somehow reversing the mistakes and mystifications that have at times meant that these people have served lengthy prison sentences. Innocents is part of a movement to update judicial breaches which have deeply affected the United States; without wanting to moralize or claim to be putting injustices of history to rights, Taryn Simon has here reinstated the possibility for the image to be at the service of the lowly, and not just the powerful, setting up a sort of documentary parallel which acts like a missing and wholesome link in the great national American narrative.

Taryn Simon, The Innocents, 2002. Courtesy Taryn Simon © Taryn Simon

It is once again a process of immersion, this time in a hub of the movement of goods—JFK airport in New York—, that gave rise to Contraband. To produce this massive output of images, Taryn Simon became involved in nothing less than a photographic marathon which, according to the artist, literally exhausted her. For several days she ceaselessly photographed the endless succession of items seized by customs. Contraband proceeds from a system akin to A Polite Fiction and also concerns an illicit production, even if the criminal nature remains quite minimal, insomuch as what is involved is the masked inscriptions on the walls of the prestigious foundation in Paris. Contraband draws from the same sources of an anonymous production, the work is, in a way, made in situ, and the production of the collection is indeed guaranteed, despite itself, by the institution housing it. Like A Polite Fiction, where the power of the photo was caught out in its capacity to describe the depth of reality, Contraband suddenly brings a collection of objects to life by removing them from their primary condition, destined to remain secret. This work deeply questions the photographic medium as a stand-in for reality: the articles seized by customs are mainly fakes, counterfeit Vuitton bags, imitation pairs of Prada shoes, and the like, whereas the photograph produces perfectly legal doubles which fuel the art market in all impunity—as with these images which will inevitably end up on gallery walls. Taryn Simon thus puts her finger on one of the collateral effects of globalization: the inability, for the administration, to control the flow of an alternative production which submerges it from every quarter. Through the American artist’s filtering lens, the attempt to curb the contraband becomes the Sisyphean symbol of a struggle lost in advance—because no legal barrier can staunch the indisputable impulse of humanity to procure these objects of desire for itself—but also the metonymic vision of the complexity of social relations caught through the host of situations evoked by these amazing lists of articles, a sort of negative portrait of the world we live in, of an at times disquieting strangeness which appears neither in glossy magazines nor in the ideal world of advertising agencies.

Oulipo-like Listings / Babel-like Angst

Taryn Simon’s systems and arrangements have a tendency to repeat themselves: identification of a production line within a context in which they appear in a clandestine or unexpected way (the hidden drawings of workers, illicit articles seized by customs, agent 007’s gadgets, etc.), in situ immersion in order to introduce the apparatus of documentary production and, where relevant, isolation of objects resulting from this procedure. These samplings and collections call powerfully to mind an entomologist’s activities, carefully singling out specimens to bring our their distinctive characteristics, somewhere between scientific rigour and an attraction to oddity and eccentricity, but they also renew the form of the time capsule, a thousand leagues from the nostalgic fetishism of an artist like Andy Warhol. In A Polite Fiction, for example, the artist put her hand on a carefully disguised treasure made not only of objects made by workers on the construction site, but also of materials stolen for their own personal use.4 These two seams were then joined together to form a truly impossible collection, reflection of a spontaneous and unintentional production. In Contraband, the assembly of objects confiscated by customs culminated in an even more eclectic collection because it was not limited either by a professional framework (that of the construction site) or a sociological one (because it was the result of an infinite number of areas of interest), and referring to the absolute diversity of the worldwide production of contraband items as well as to the multi-polarization of production.5 These assemblies of items making up Simon’s works call to mind, at times, the writing procedures of the OuLiPo—Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle—which apply restrictive systems meant to limit the author’s freedom, and, in the end of the day, turn out to be fertile sources of literary creation.

Taryn Simon, Contraband, 2014 . Courtesy Taryn Simon © Taryn Simon

In the case of A Polite Fiction, the way the exhibition is produced raises the question of the definition of the work of art by offering a somewhat original response to it: objects whose existence sidesteps, in advance, the artist’s knowledge, and which only come to life after being activated in accordance with a procedure painstakingly complied with, to do with exhumation and revelation. In Birds of the West Indies, the listing of the objects selected by the artist and photographed by her also gives rise to an accumulation of objects which are nothing if not interesting from the angle of their specific nature—above all if we consider that the actresses are part and parcel of this series of objects—; just as in Contraband, the list is truly huge.

Leaving aside certain extremely rare examples, as in A Polite Fiction, Taryn Simon never shows these objects directly: they are always “filtered” by the camera lens before being reinstated in the form of photographic documents and archives, more or less truncated (as in The Picture Collection where the system of stacking chosen masks many of the documents) or more or less staged (as in Birds of the West Indies, where the presentation of the Bond-like gadgets on a black ground lends them an undeniable affectedness. The fact remains that, like any photographer, Simon does not create sculptural objects or novel, as yet unshown, forms; she acts in this “tongue-in-cheek” way, where creation is concerned, which consists in assembling, putting together, listing, sorting, exhuming, and so on, based on an iconographic resource coming from her own work, but also from a potentially unlimited exogenous heritage. The inevitable outcome is an output essentially based on a twofold levelling, that of the medium itself, and that applied by the artist through the homogenization and systematicness of her presentation formulae.

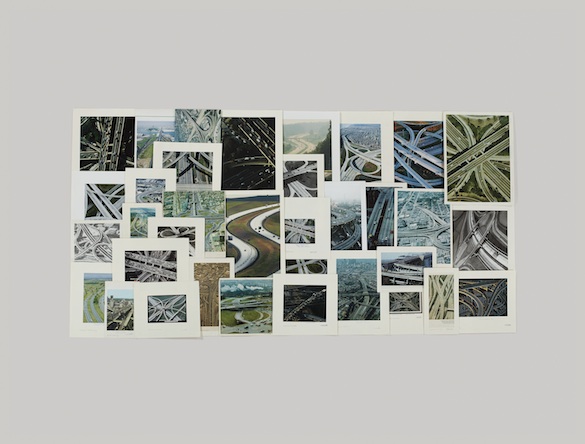

Taryn Simon, The Picture Collection, 2013. Highways. Courtesy Taryn Simon © Taryn Simon

This twofold flattening echoes a more general historical tendency which refers to the erasure of the hierarchy between high-brow and low-brow culture which appeared towards the end of the 20th century6, and whose high point tallies with the peak of the recourse to the archive at the dawn of the third millennium. Tacking between an assemblage of documents with many different origins, a denunciation of ideologies conveyed by the image, and the confiscation of its power for different propaganda purposes, Simon is extremely aware of this levelling of differences which re-defines the uses of a popular medium in the way it is produced and received. For the making of The Picture Collection, she singles out the fact that this phenomenon was already at work when the institution of the same name came into being in 1915,7 well before various art movements appropriated the phenomenon and turned it into a commonplace: the public collection was in fact formed on the basis of an extraordinary mixture of purchases, bequests and free loans of every conceivable kind, hailing from all the different media existing in the United States between the wars, subsequently augmented by the input of works of photographers as emblematic as Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange. Those artists who fed the collection with their gifts were keen for it to remain accessible to ordinary people, espousing a line of pure democratic thinking. Taryn Simon takes part in this movement by introducing into one of her series a work by Edward Steichen interposed between two pictures taken by anonymous photographers. Her interest in the erosion of cultural differentials finds logical extensions in her approach to the Internet: in a way, the collection foreshadowed the way the web works, and anticipated its development which, starting from a utopia based on a democratic sharing of knowledge between scientists, gradually evolved towards a great big junk room controlled more and more by the giants of the computer industry, and institutions of globalized surveillance. The artist has continued her investigations into the reception and use of images with a project devised in collaboration with the computer scientist Aaron Swartz: Image Atlas is a search engine which makes it possible to combine the findings of searches resulting from local engines, based on any old word and its optimized translation by Google Translate in the sixty countries which have been used as a sample. The list of found images varies from one extreme to the other, in relation to the countries in which the searches take place—for example, the word “grocery” will encompass images of a fruit stand in France, 2 lbs. of flour in the USSR, and a robot in Syria [sic]—thus highlighting the way in which these searches are reliant on the vocabulary available to Google, but also the way in which they are steered by local cultural and political agencies, which have an indirect influence on the establishment of the general outline of the articles being searched for. In the extension of this line of thinking, Simon also notes that, by dint of bringing the most searched items into the top results, search engines end up by removing all power of discovery from these tools which are intended to make things easier, and in the end fizzle out in tautology.8

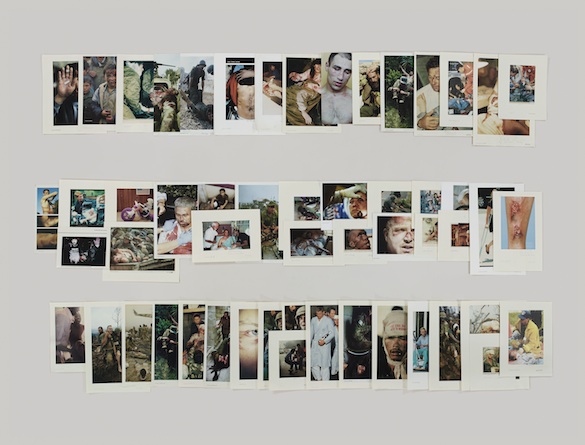

Taryn Simon, The Picture Collection, 2013. Wounded. Courtesy Taryn Simon © Taryn Simon

Taryn Simon’s œuvre is like The Picture Collection, whose nomenclature, created in its early days, seems capable of holding at bay an anarchy inherent in an entropic system, a ground-breaking utopia which calls to mind the one which had precedence at the birth of this new encyclopaedic monster called the Internet, which the New York public collection in a way foreshadowed by announcing dysfunctions to come and the desire to control this free upsurge of knowledge. The artist wavers between an attempt to organize chaos and letting it just happen, and allowing herself be borne along by it: in A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters 1 – XVIII, the strict organization in three sections which documents the research carried out over a four-year period into family genealogies, which caused her to travel right round the world, arranges in its centre various spaces where the narrative is fuelled by all the world’s invisible blackness, which no photographer can express; it is in this space that the image negotiates with the text which the artist invites spectators to traverse…

Taryn Simon, Chapitre XI A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I–XVIII, 2011. Courtesy Taryn Simon © Taryn Simon

1 The least that can be said is that we are well removed here from the canons of a functional architecture designed to optimize the volume of spaces given over to exhibitions. Involved here, above all, is a luxurious box which in no way renews Gehry’s vocabulary, a signature or rather a label which can be instantly identified, from Bilbao to Los Angeles. At least in Paris, unlike Bilbao, exhibition venues have been dealt with apart and rendered autonomous in relation to the “sails”, offering nothing less than white cubes. On this, see the discussion : “art is just a luxury product” (http://www.sitaudis.fr/Incitations/l-art-n-est-il-qu-un-produit-de-luxe-n.php).

2 This lies at the heart of the artist’s praxis, the discrepancy between what is shown and what is captioned and/or matched by a text. Some see in this a Brechtian distancing which enables the spectator to slip into the interstice so as to participate directly in it; others see in it a reference to Rancière’s thinking when he talks about the intertwining of intentions and references in The Emancipated Spectator. Note that the reference to Rancière seems altogether appropriate for an understanding of the stacks in The Picture Collection where, as Tim Griffin notes in his accompanying text, the documents are partly masked and need to call upon an iconographic culture in order to complete these series, even though ignorance about this culture does not, following Rancière’s theory, prevent us from understanding the work, based on a whole range which remains thoroughly satisfactory.

3 Daniel Baumann, “The Black Hole”, in Birds of the West Indies, p. 19, Hatje Cantze, 2013.

4 One thinks here of Jean-Luc Moulène’s Objets de grève/Strike Objects, made by workers on strike, and also forming a collection of objects that cannot be pigeonholed.

5 “The sheer repetition of objects (endless accumulations of counterfeit luxury handbags, every time the same; bottomless supplies of sexual stimulant drugs; meat products; pirated DVDs; animal parts used as medicine or for religious rituals) presents a metonymic view of the social whole, as constructed by our endless drive to accumulate; an overproduction of stuff.” Hans-Ulrich Obrist, “Ever airport : notes on Taryn Simon’s Contraband”, May 2010, published in the catalogue for the exhibitions “Vues arrières, nébuleuse stellaire et le le bureau de la propagande extérieure” at the Jeu de Paume, Paris, and “A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I — XVIII”, at the Point du Jour, Cherbourg.

6 “Oppositions of high and low, elite and popular, modernist and mass, have long structured discussions about modern culture. They have become second nature to us, whether we want to uphold the old hierarchies, critique them, or somehow overthrow them. They always have borne on matters of class; indeed there is one system of distinction—highbrow, middlebrow, and lowbrow—that explicitely refers differences of culture to differences of class (both of which are understood in a pseudo-biological way). Yet what if this brow system has undergone a lobotomy before our very eyes?” Hal Foster, Design & Crime, Verso, 2002.

7 The Picture Collection of The New York Public Library is a collection of more than one million photographs, posters, prints, original post cards and pictures taken from books, magazines and newspapers, and classified by subject. The collection is open to the public six days a week, and items may be taken out on loan. 30 000 images have already been digitized.

8 Cf. Tim Griffin, “Unlikely Futurity” in The Picture Collection, Cahiers d’Art, 2015.

Taryn Simon

“Birds of the West Indies”, galerie Almine Rech, Paris, 21.02 – 14.03.15

“Rear View, A Star-Forming Nebula and Office of Foreign Propaganda”, Jeu de Paume, Paris, 24.02 – 17.05.2015

“A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I — XVIII”, Le Point du Jour, Cherbourg, France, 1.03 – 31.05.2015

- From the issue: 74

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Jack Warne, Alun Williams, Ben Thorp Brown, Mircea Cantor, David Horvitz,

Related articles

Gregory Sholette

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Vera Kox

by Mya Finbow

Fabrice Hyber

by Philippe Szechter