Éric Baudelaire

The Music of Ramón Raquello and his Orchestra, Witte de With, Rotterdam, 27.01—7.05.2017

After walking past an old transistor radio, with Orson Welles’s voice announcing an attack on the United States by extra-terrestrials being regularly interrupted by the fictitious music group Ramón Raquello and his Orchestra, it is with the film Sugar Water, made in 2007, that Eric Baudelaire’s show at the Witte de With opens. An opening which, in many respects, resembles a discreet punctuation as much as an exhibit. The film is screened on a small monitor placed on the reception desk on the second floor. An invitation to watch the film in fragments. The fact is that, in a long sequence shot, Sugar Water represents precisely a fragmented scene: in an imaginary Paris metro station, a bill-poster affixes to the wall a first image which he then covers with a second, a third, and finally a fourth, to represent four stages of the explosion of a car; otherwise put, four frozen split-seconds of an action in continuous motion. Invariably linked, time and fragmentation run through the exhibition with each step the visitor takes. To draw him where? This is where Eric Baudelaire’s approach calls for an overall eye. What do we have before our eyes? Films, photos, texts, archives, and signs which answer each other and steal away from us. And Baudelaire becomes a new Chevalier Dupin alongside whom, like Edgar Allan Poe’s narrator, we let ourselves be guided in order to grasp the enigmas and traps of an investigation that has become an exhibition. Unless it is the other way round.

Let’s start with one of the latest works: FRAEMWROK, FRMAWREOK, FAMREWROK… Behind this title, where each letter seems to be jostling until the possibility of a word springs forth—and thus the meaning it might give rise to—, lurks an impressive collection of archival documents whose subject is terrorism. It is in the form of wallpaper with photographs added, covering several walls, that the work can be read. But in no time at all dizziness sets in. These newspaper articles coming from many different sources, complementary but contradictory, too, filled with graphs and statistics, expose the complexity of the subject and make the outlines increasingly abstract. An abstraction that is well illustrated by the bokashi, that Japanese technique designed to censure pornographic images by scratching them with a fine blade. “Be advised that I am hiding something from you, this is the active paradox that I have to sort out: at the same time, it is important that we are advised and not advised: that it be known that I don’t want to show it.” What is true for passion, according to Roland Barthes in his Lover’s Discourse, is also true for this art of dissimulation, and even more so when Eric Baudelaire decides to repeat and enlarge the licentious and “hidden” motifs by a series of heliogravures, and when a film, [SIC], seems to push the procedure to the point of absurdity, until there issues from the censor’s gesture, as is observed by Homay King, “a space where the eye can wander freely.”

With Eric Baudelaire, something seen invariably suggests another thing. So the double projection of slides titled Déplacement de site involves images that are at once near and far. The artist responded in his own way to a commission by the city of Clermont-Ferrand, Michelin’s realm, by asking an Indian photographer to produce, in India —a country where the tyre manufacturer has relocated to— some photographs which resemble as closely as possible a series he produced earlier in the Auvergne city. In other words, a dialogue created between two territories and two time-frames in a deceptive mirror effect.

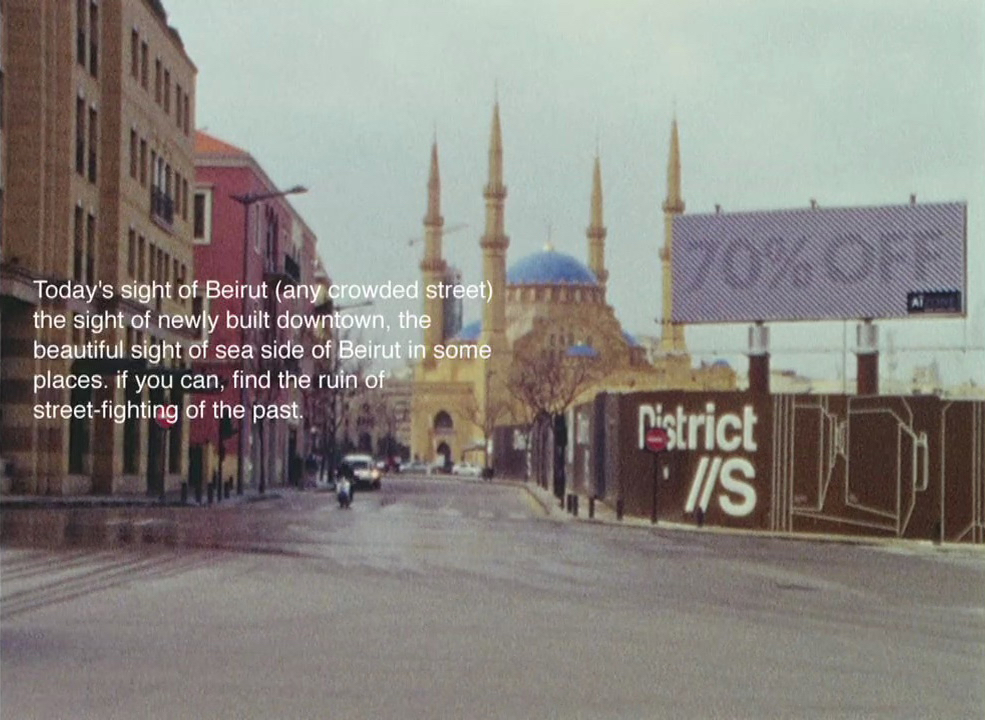

Dialogues are once again involved in the body of work titled The Anabasis of May and Fusako Shigenobu, Masao Adachi, and 27 Years without Images. This is a wander between past and present, Beirut and Tokyo, Masao Adachi, an activist film-maker, and May Shigenobu, whose mother, Fusako, was involved in the revolutionary cause. A wander in different registers of imagery, produced with a super-8 film intermingling images of Beirut and Tokyo, and overlapping portraits of the people mentioned in the title, slides reproducing Masao Adachi’s drawings when he was a prisoner in Beirut, an excerpt from his film AKA Serial Killer, and black monochromatic photos. A wander which the first word of the title already invites us to make, in memory of those lost mercenaries keen to get back home, whose tale was told by Xenophon, later inspiring Saint-John Perse and Paul Celan, and in which, more recently, Alain Badiou read the symptoms of our day and age in quest of meaning.

So the most recent work is an extension of this, becoming the final exhibit in the show. The film AKA Jihadi resembles an investigation into a young man who had enlisted on the Al-Nusra front in Syria. Anti-spectacular, following the fukeiron theory developed by Masao Adachi, whereby all landscape is associated with a figure in the predominant power, a theory already at work in L’Anabase, the film shifts from landscape to landscape, between France, Algeria, Egypt and Turkey, as far as the threshold of Syria, visible behind a huge wall. The director treads in the young man’s footsteps, while the police inquiry about him intersperses this “journey” with reproductions of different documents to do with the statement. Documents to be read in an almost silent film, from which speech has been removed, whose main subject/suspect is no less removed, with the exception of furtive snapshots taken by a surveillance camera. But is it really him? We must agree to believe it is and see in these images what they are intended to show, and thus overlook the essence: what they are really showing…

(Image on top: Éric Baudelaire, The Anabasis of May & Fusako Shigenobu, Masao Adachi, and 27 Years without Images, 2011. Super 8 / HD video, 66 minutes. Courtesy Éric Baudelaire.)

Related articles

GESTE Paris

by Gabriela Anco

On the High Line

by Warren Neidich

Lyon Biennial

by Patrice Joly