Marta Gili & Osei Bonsu

The Jeu de Paume is celebrating the first ten years of Satellite, a nested programme which is held every year in four chapters, with as many artists and a guest curator. Started by Marta Gili when she arrived to run the institution in 2007, Satellite has been relayed by the Maison Bernard Anthonioz at Nogent-sur-Marne and the CAPC in Bordeaux since 2014. A chance for the programme’s instigator to mull over her line of thinking and the issues gravitating around the programme and the institution. Her ideas overlap with those expressed during another conversation with Osei Bonsu, the curator chosen to oversee the tenth edition titled “The Economy of Living Things”. He talks about his vision for a programme that he has just started to organize. Overlaid impressions.

Why did you initiate this programme when you arrived as director of the Jeu de Paume in 2007?

Marta Gili: I think training curators is really important and I wanted to set up a kind of annual residency, like the one created at the Fundacio La Caixa in Barcelona. In the case of the Jeu de Paume, which is, let me remind you, an art centre, I found it relevant to invite curators and artists and give them a chance to produce a work. The main aim of the Satellite programme is that each curator has the possibility of working around a subject, and then with the Jeu de Paume’s different departments (exhibitions, management, communication, publishing, visitors …), as well as with other institutions: the Maison d’Art Bernard Anthonioz at Nogent-sur-Marne (because the Fondation Nationale des Art Graphiques et Plastiques, which it is the art centre, has been a Satellite partner since its launch) and the CAPC in Bordeaux. So there is both a conceptual and an institutional approach. This programme is also designed so that the teams work in contact with people who contribute different ideas and upset their habits. It’s an exercise which has deeply affected us.

Osei Bonsu: We’re always tempted, because we’re guests at the institution, to disturb their way of doing things, just a tad. There’s something about the attitude of French curators which I admire: their ability to upset and re-organize an institution’s energy. I’m thinking in particular of Nicolas Bourriaud, who, in his exhibition “Traffic” at the CAPC, really managed to raise the question, through the show, about public participation. Satellite offers you one year to construct four narratives around exhibitions, in particular through books and activities for the audience. If you don’t grasp the opportunity to ask the institution questions, you might as well put on any old exhibition.

Osei Bonsu: We’re always tempted, because we’re guests at the institution, to disturb their way of doing things, just a tad. There’s something about the attitude of French curators which I admire: their ability to upset and re-organize an institution’s energy. I’m thinking in particular of Nicolas Bourriaud, who, in his exhibition “Traffic” at the CAPC, really managed to raise the question, through the show, about public participation. Satellite offers you one year to construct four narratives around exhibitions, in particular through books and activities for the audience. If you don’t grasp the opportunity to ask the institution questions, you might as well put on any old exhibition.

The programme’s format has developed in ten years, taking a different direction about four years ago. By inviting Raimundas Malasauskas and Mathieu Copeland to come up with exhibitions in 2011 and 2013, you seemed to be keen to promote author-curators whose exhibition proposals were often quite rhetorical, and explored the actual issue of the exhibition. Since then the format has narrowed around a simpler arrangement in which video is the imposed medium. Why this change?

M.G.: There are in fact curators who carry out exhibition tests that are almost ontological, like the ones you mention. The goal of their approaches was not solely to produce in order to show, it was to question the display itself. Others, and in particular the latest guest curators, work more with the artists by creating a narrative between them. This doesn’t mean that we’re attached to one form of curating more than to another. Since 2012, however, curators have only proposed video productions to the artists. This makes it easier to circulate works between the different venues represented by the Maison d’Art Bernard Anthonioz, and the CAPC. What’s more, few institutions are focusing on the specific production of this medium.

Satellite 6. Mathieu Copeland : « Une exposition sans texte. Suite pour exposition(s) et publication(s), 3ème mouvement », MABA, Nogent-sur-Marne © Jeu de Paume, Romain Darnaud

O.B.: The idea of being a “satellite” curator is to be able to move around and within the institution. The specifications provide for a video element, but I’ve tried to emphasize, among the artists, the fact that, if they want to extend their vision beyond this medium, this was possible too. In the first Satellite 10 show, whose programme I’m in charge of, Ali Cherri is presenting his new video Somniculus, as well as a light box on the mezzanine of the Jeu de Paume, and a table with fragments of archaeological objects at the CAPC. In a movement akin to his video, these elements form an archaeological experiment around objects and the meaning they take on when they are removed from their original context. When artists work with video, they don’t really have any place to hide. Someone told me that video is the frontier of contemporary art: it is quite direct and moving, and in many instances rooted in a narrative, even if it is not meant to be immediately readable. The artists in the Satellite programme are invited on these premises. They understand what the medium is and are well acquainted with its history.

The Satellite programme fills the institution’s “interstitial areas”: a mezzanine in the stairway leading to the basement, the lobby at times, more recently a screening area… Despite its interest, there’s not much about the programme in the media. Why such a discreet programme?

M.G.: I don’t think the word “discreet” can be applied to the Satellite programme; the problem is that, on the whole, the production of works by emerging artists is sometimes handled rather discreetly by the media. It’s true that the Satellite programme is located in areas that were not dedicated to exhibitions, but I think, in a general way, that contemporary production is not very media-oriented; the media prefer to deal with known and recognized things.

Since 2012, we’ve been co-producing the programme with the CAPC, which is the very opposite of the Jeu de Paume in terms of space and visibility. I’m truly all the more delighted about this because Maria Ines Rodriguez, the CAPC’s director, was the second curator in the Satellite programme, which just shows that curators who’ve been involved in this programme have really become leading figures in contemporary art.

O.B.: When we talk about exhibition venues, what we often overlook—which is perhaps more important than the area of the Jeu de Paume—is the physical dimension of the city. I hope that when people come to see the Ali Cherri show, they will then take the metro to go to the Kadist and take part in a conversation about contemporary art and archaeology with a community which is not the same as the Jeu de Paume’s public. I think it’s more important that artists have a sense of their audience rather than the space that is assigned to them. In a culture of biennials, artists don’t really have a chance to grasp the ecosystem around the place which will house their work. All the more so because, in my view, there is a particular intellectual history which really belongs to Paris, which must be taken into account.

Echoing the spatial arrangement of the programme, carte blanche is often given to curators and artists who are keen to explore the interstices and gaps in the predominant, and especially European, history. The proposals made by the curators Erin Gleeson and Heidi Ballet espoused the viewpoints of a Fijian scientist, of the Cham ethnic group in Vietnam… A way of experimenting beyond the monographs often devoted to European figures, which have little room for post-colonial issues?

Satellite 7. Natasa Petrecin Bachelez. Kapwani Kiwanga. « Maji Maji » © Jeu de Paume, Romain Darnaud

M.G.: One of the reasons why we decided to work with video is that, from a budgetary viewpoint, it enabled us to invite artists living faraway, whom we couldn’t pay a lot to travel. I’m convinced that post-colonial history is deeply connected with film narrative. The medium makes it possible to associate several micro-narratives which are dovetailed, and which we didn’t think could communicate. And this often makes it possible to make a personal history based on the histories of others. Unless the opposite is the case. This was so with the programming of Erin Gleeson and Heidi Ballet. This idea of an exploding frontier has to be re-thought within the institution. We have to get rid of the idea of very expensive transport and insurance. Creation today advocates a freer and more democratic circulation of images.

O.B.: Most European institutions have opened up their programming to several international artists who are now better represented. As a curator born in Ghana, and brought up in England, I’m obviously very involved with the issue of internationalism. And since I’ve been in Paris, I can see an interesting landscape taking shape with the Jeu de Paume, the Kadist Foundation, the Villa Vassilieff, and Bétonsalon, even while the climate in France is going through the same conservative changes we can see internationally.

Since it was created, Satellite has presented a certain number of projects which have dealt with the issue of invisibility (ghosts with Nguyen Trinh Thi, empty spaces with Tomo Savić-Gecan) and played a lot on orality. Connected with post-colonial issues, is this a programme which, in your view, questions what the image doesn’t express?

Satellite 7. Natasa Petrecin Bachelez. Natascha Sadr Haghighian « Ressemblance », MABA, Nogent-sur-Marne © Jeu de Paume, Romain Darnaud

M.G.: What the image doesn’t show, the invisible, is a theme of almost all the shows at the Jeu de Paume, and not just of the Satellite programme. But it’s true that much of the contemporary art that interests me and the guest curators is the art that focuses on displacing and bypassing official narratives. The interest of here combining words is not simply to do with expressing what one doesn’t see, it’s to summon other images which don’t exist or which one has been able to see elsewhere, and which we include in our personal narrative. In this age of image circulation, I don’t think we can invent new ones, but we can create new (hi)stories thanks to their editing, montage and superposition.

O.B.: For me, holding exhibitions is having the privilege and responsibility to tell certain (hi)stories but above all the present. Giving the present a presence, this seems to me to be the main thread of “The Economy of Living Things” and most of the Satellite programmes.

Satellite 4. Raimundas Malasauskas. Alex Cecchetti & Mark Geffriaud. THE POLICE RETURN TO THE MAGIC SHOP – La Guerre, Le Théâtre, La Correspondance © Jeu de Paume, Arno Gisinger

The space/time division of the Satellite programme also seems to permit experimentation with other forms of narrative, and longer and more fragmented forms on the sidelines of the linear layouts of the monographs that you have encouraged since your arrival at the head of the Jeu de Paume. What does this different relation to time bring? Why is it important?

M.G.: Time is what makes the strength of the programme. What’s important for us is to work for a year with a freelance curator on four projects. That person becomes part of the team. The time-frame is in effect fragmented because each Satellite show opens at the same time as our other shows. This is why, at the end of the year, the four publications devised for each project are very important. The collection of books is what remains and why it remains. Again in this attentiveness to creation, the fact of giving carte blanche to young graphic designers makes it possible to work with other areas of creation and keep an editorial trace of these 10 years of Satellite programmes. The project is established in time, and it is not very visible, but it stays there over the years. It’s like art education, it’s something that is worked on with time.

O.B.: This year, the idea was really to create links between the shows and institutions, and not think of the artists independently of each other. The four guest artists will be brought together in a group show at the MABA, which, to my knowledge, had not been done before. A symposium will also bring them together at the same time to discuss their activities in a more general way. This is a way of making them the players in a discourse which is rooted in the institution, and not just attached to it. In a way, they must be a form of virus, entering the institution and making an incision in it to look inside.

Satellite 3. Elena Filipovic. Mathilde Rosier. Trouver des circonstances dans l’antichambre © Jeu de Paume, Arno Gisinger

What will the programme become? Will it take on new directions?

M.G.: We thought a lot about this and we’ve decided to carry on our approach, because we’ve concluded that the wealth of the Satellite programme is polyphonic: a residency for a guest curator, production of artists’ works, working with emerging graphic designers, lectures, performances, screenings, shared experiences with other institutions… In a word, not being in a state of inertia, prejudice and comfort. I’ve learnt a great deal in the exchanges with all the people involved in the Satellite programme, because they give us a chance to see ourselves differently. Institutions have got to accept movement as a leitmotif.

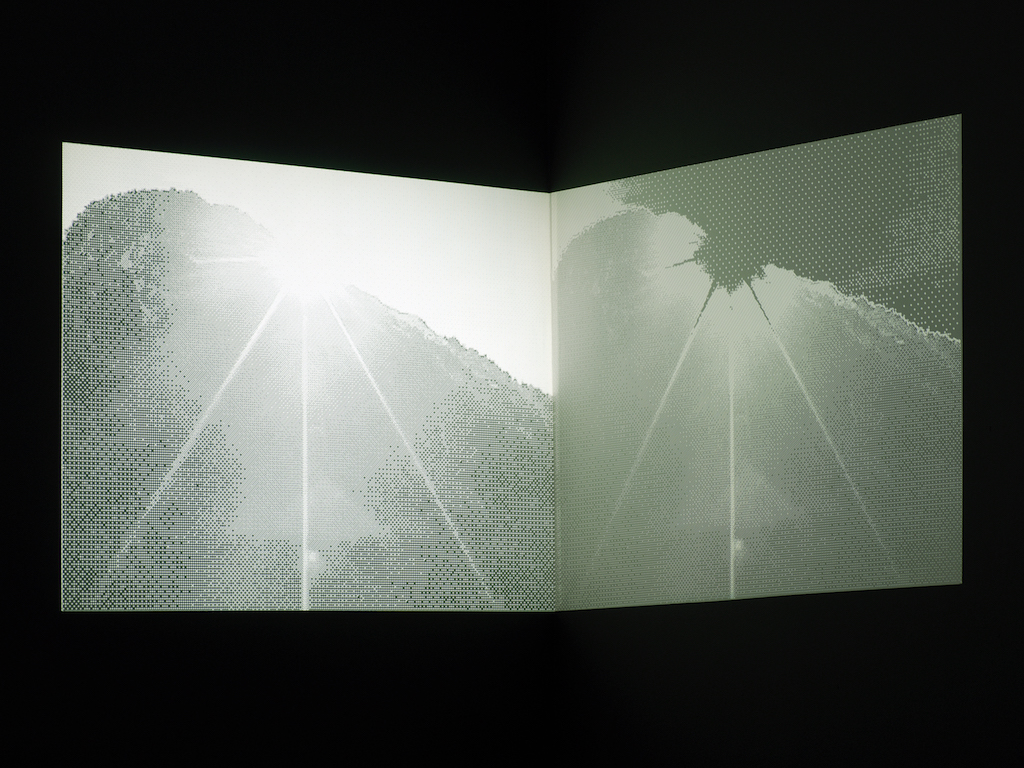

(Image on top: Ali Cherri, Somniculus, 2017. Shooting view. Courtesy Ali Cherri. Coproduced by: Jeu de Paume, Paris; FNAGP; CAPC, Bordeaux.)

- From the issue: 81

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Invernomuto,

Related articles

Céline Poulin

by Andréanne Béguin

Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Interview with Warren Neidich

by Yves Citton