Wilfried Huet / GAGARIN

GAGARIN has just had its final sortie into “review” space, after making 33 revolutions in the ever more cloudless skies of freelance publishing. The Flemish comet which has seen passing through its pages, with their delicate ivory hue, the cream of the international art establishment, has decided to come back down to earth after a lengthy sojourn in the upper spheres of international art. The textual flights of its guests have always managed to find in the person of Wilfried Huet an enthusiastic welcome, with the commander of this international shuttle defining himself as a pioneer of free publishing, and claiming a posture of fierce independence in the face of the diktat of authorized criticism and the hegemonism of the English language. A hardline Belgian merrily blaming on his Belgianness to explain the great and on-going differentness of his editorial choices—erected to the rank of nothing less than a method—by referring us, by the same token, to the unfathomable split in the land of Magritte and Broodthaers. Two exhibitions, one in Ghent, the other in The Hague, celebrate the end of this publishing adventure, mixing references to Greek myths with allusions to the conquest of space.

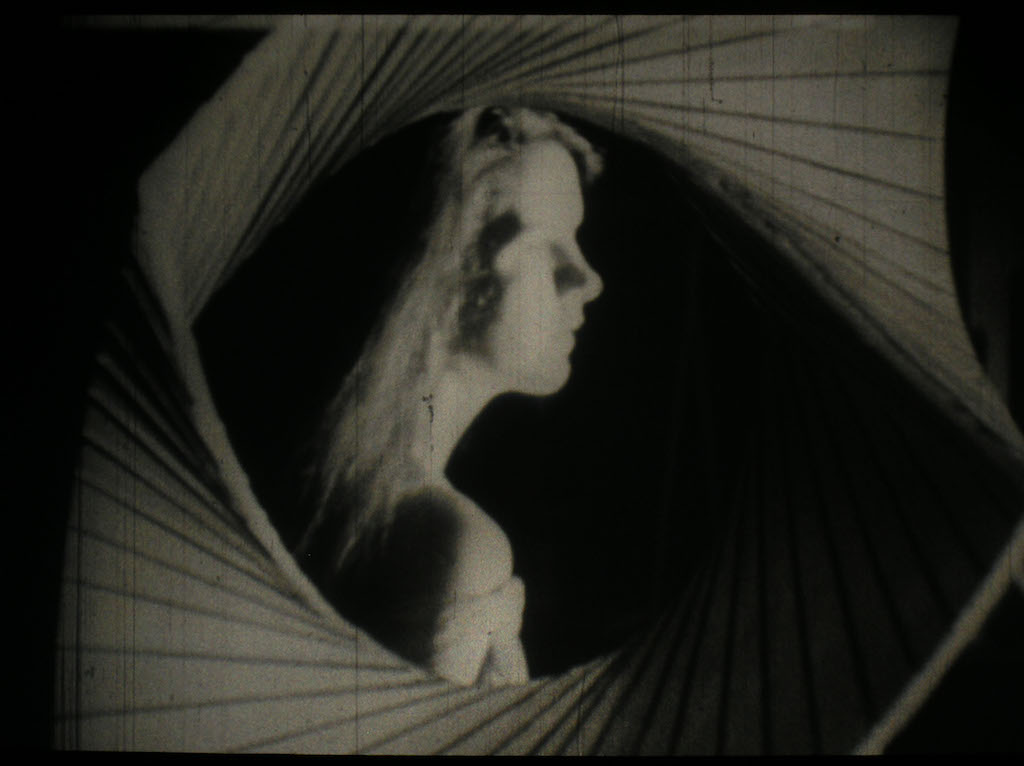

Maya Deren, Witch cradle, 1943. Silent film 12′. Courtesy LUX, London. « The String Traveller », S.M.A.K

Patrice Joly: How was GAGARIN born, and with what in mind did you create it?

Wilfried Huet: I launched GAGARIN in 2000, in the wake of the opening of the two contemporary art museums in Flanders, during the previous decade, the S.M.A.K. in Ghent and the Mukha in Antwerp, when those great institutions of contemporary art started to attract art world graduates. Before that, things were simpler, you might cross paths with James Lee Byars, Joseph Beuys or Carl Andre in the streets of Antwerp, and there were plenty of great artists in the galleries roundabout—they were easy to approach. But art critics trained at university have a tendency to want to take up a position between the artist and the public: as far as I’m concerned, I’m not in favour of preferring any particular period, but I tend rather to be for a direct relation between the public and artists. When an editor of De Witte Raaf wrote a series of articles appraising the quality of the contemporary art museums in Flanders, titling the last of the series “crematorium”, as a sign of his loathing of their collections, and giving marks to the artists in question, I said to myself that the time had come to let these latter have their say again. GAGARIN was aimed at those who don’t have the patience to wait until the moment when everything is staked out and coded, and are ready to take shortcuts in order to find a stimulating art and ideas that are still fresh.

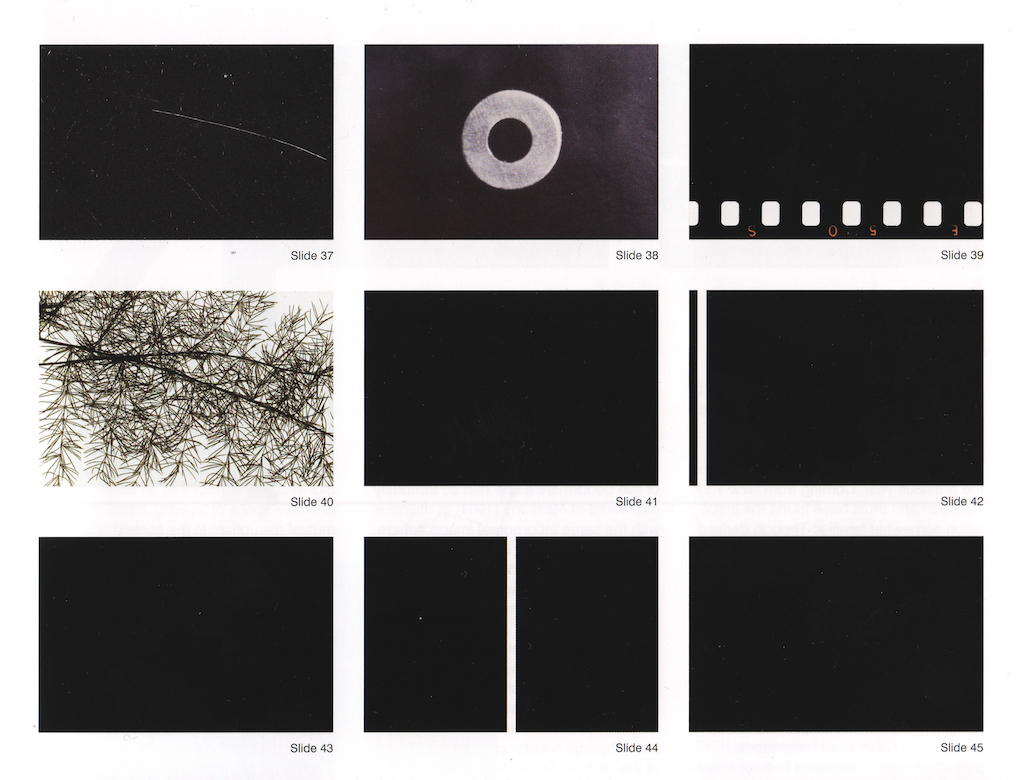

Anthony McCall, Miniature in Black and White, 1972. Contact Sheet. Courtesy Galerie Thomas Zander, Köln. « The String Traveller », S.M.A.K

Where does the name GAGARIN come from?

The GAGARIN recipe was so against the grain in relation to what existed at that time in terms of magazines, and it was also so expensive to publish a magazine that, with so little money at my disposal, I tended to see myself like a modern Icarus, but also like an artist’s alter ego, like someone keeping his distance from society, arriving with the experience gleaned in a gallery in a small town to work in publishing: so I thought that GAGARIN was a very well chosen name for the project.

Bernd Lohaus, Untitled, 1969. Rope, 25 × 75 × 65 cm. Courtesy Estate Bernd Lohaus. « The String Traveller », S.M.A.K

But wasn’t there also the idea of linking the name to the conquest of space, to science-fiction, to that Cold War period, but also to a contemporary saga combined with a scientific utopia?

What is the concept that prompts you to publish artists in their original language rather than directly in English? How do we explain this extremely special structure of GAGARIN?

Latifa Echakhch, Encrage, 2014. Cardboard box, vinyl records of works by Johann Sebastian Bach, Indian ink, wooden cloud scenery, canvas and acrylic paint, 500 × 180 × 110 cm. Courtesy Latifa Echakhch. « See How The Land Lays », West Den Haag.

All the texts are translated into English but, yes, they also appear alongside their original version, regardless of the language. For me this is a way of linking an editorial concept with an exhibition concept, the one I put on in 1979 in Antwerp—an exhibition for one day—at the Voormalige spoorwegbedding van de Schaliënstraat, where I put 26 paintings in the street with a gap of 6 metres between them, without there being any formal link between the works, whence the size of the gaps. It’s the same structure that I tried to reproduce in GAGARIN. The choice of the first artist was crucial: I tried to find an artist in whom I felt the possibility that he would send us a text (I admit that it was totally based on hunches), then I chose the second, in complete contrast with the first, and so on and so forth. I stopped after eight artists. Needless to say, the choice of the first artist was determined by my taste, and that choice to alternate totally opposed artists was also a way of getting beyond that arbitrariness. But that also corresponded with my origins, half-French, half-Belgian, with the southern French half referring more to the harmonious aspect of things, while the northern half corresponds more to contrasts, and as a Belgian, I was caught between those two movements: I get the impression that my choices tally with that dichotomy. As far as art is concerned, GAGARIN can also be regarded like a barometer of the world’s globalization: sixteen years ago, it wasn’t obvious to welcome a South American artist, whereas nowadays that is something quite run-of-the-mill.

When I started GAGARIN at the end of the 20th century, there were lots of artists who were top-down, with unassailable statures, like Henry Moore, Francis Bacon, Pablo Picasso, and so on. They made good use of art critics who established a bridge between the public and themselves. But nowadays the artist is more open, he often creates his work with the immediate participation of the public. He tends to demand of you the same things as he does in his own work, he tries to enter into a very close communication with you. A good example of this is Javier Téllez, who’s made an extraordinary film, One Flew Over the Void3, in which we see an acrobat cross the US-Mexico border, propelled by a cannon: artists like Téllez are already communicators, but they are also ready to pass by way of another form of communication, and it’s precisely at that particular moment that I feel they are ready for GAGARIN. Most of them are also very interested in the magazine’s recipe, because it offers them a totally novel chance to come up with an editorial production that is equivalent to the experimental dimension of their works.

What have the finances of the magazine been like, and could you exist right now without the backing of the S.M.A.K.?

Gagarin n°19, 2009. Image : Ed Ruscha, Country Cityscapes – Noose Around Your Neck, 2001. Courtesy Ed Ruscha, photo : Will Lynch.

This is a question which I’ve never thought about, because if I started to think about it, I would never have put out those 33 issues of GAGARIN… The first issue was published thanks to the support of a small town of 10,000 inhabitants, Waasmunster, where I ran an independent gallery at the time—that was before the S.M.A.K. existed—in which I held shows almost without any money, borrowing straight from artists and collectors—Magritte’s wife lent me some of her husband’s works and I even showed a Jacob Jordaens—the public came from Brussels, Ghent and Antwerp, and I decided to stop at the 100th exhibition: I’m always anticipating the final “episode” of a “series” when I start something, as I did for GAGARIN with the 33rd issue. The town’s mayor suggested that I carry on by means of a more substantial support and, at that moment, I proposed the GAGARIN project, as I had imagined it, and he gave me a sum of money. The Ministry of Culture refused to subsidize me because it reckoned that GAGARIN was too much a work of art and not enough of a magazine, because its columns included neither criticism nor reviews. Everything I was able to earn elsewhere, giving classes in particular, was invested to keep the magazine alive. Ten years after it was created, I was approached by the director of the S.M.A.K., Philippe van Cauteren, who proposed a collaboration with the museum. I waited six months before I responded, so as to be sure, let me add, that I would keep my independence, and because it was a collaboration that showed a great deal of respect for the magazine, I did agree. They really did provide very strong support for GAGARIN by organizing symposia, encounters and events focused around the magazine: they were real fans, I got about 15,000 euros a year. But now it’s over, the only resources are the magazine’s sales, and the “box” which holds all the issues.

Isn’t it a bit redundant to exhibit a magazine like GAGARIN which is already, in a certain way, the work of a curator-cum-auteur?

Guillaume Bijl, Nieuwe Demokratische Partij (A New Democratic Party), 2016. Installation, 500 × 800 × 1100 cm. Courtesy Guillaume Bijl. « See How The Land Lays », West Den Haag.

There are several ways of putting on exhibitions. I rather got the impression at the S.M.A.K. and in The Hague that I was making films, there’s such a dynamic in these exhibitions, I work with spaces, the contrasts between the works, something that you actually find in every issue of GAGARIN. I’d already put on a major show at the S.M.A.K. in 20101 for which I cut out the spine of the magazine and put the pages end to end, making a line of more than 600 metres. The museum was too small to fit them all in, we even had to use the corridor: it really was the magazine that was exhibited there, “physically”. What is being shown, on the other hand, in the exhibitions at The Hague and in Ghent is more the spirit of the magazine, its concept.

You’re ceasing its publication partly for financial reasons, but you also say that the end was programmed, even stopping with issue no33… Why this number?

Yes, it’s a biblical number, but I don’t think that’s what made me make up my mind… GAGARIN is three series of 11 issues, the first eleven are all based on the same model, with a handwritten and anonymous inscription which always uses the same text, the editorial stance, that you find on the first page of the magazine. With no12, I changed the cover by bringing in an image that was connected with with this same text. For the third eleven, I put each time a small image on the cover which was linked with the real Gagarin and the pursuit of space exploration. So three elevens in the end. If I add a series that would make 44, and it’s not as interesting as a figure as 33, and what’s more it would mean me carrying on for five more years and I’m not sure I could keep going to the end… Might as well finish with a flourish, with a beautiful issue.

Is there a life after GAGARIN?

I’m thinking I might get involved in social institutions, what with all the age of Trump has in store for us, I think there’ll be plenty to do. Maybe I’ll take care of foundlings, those abandoned children earmarked for adoption who are tossed from one foster family to the next. But I might make a western…

1 GAGARIN the Artists in their Own Words – The First Decade.

2 In reference to Italo Calvino’s novel, Invisible cities, in which reference is made to the fact that cities have their cosmic double in the form of a constellation at their zenith.

3 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qkbLCBZCvKM

The String Traveller, S.M.A.K., Ghent, 27.01.17 – 16.04.17, with Leonor Antunes, Jack Arnold, Rosa Barba, Maya Deren, Marcel Duchamp, João Maria Gusmão + Pedro Paiva, Bernd Lohaus, Anthony McCall, Roman Ondák, Amalia Pica, Michael Ross, Grazia Toderi, Marilou van Lierop and a reference to Pablo Picasso.

See How The Land Lays, West Den Haag, The Hague, 02.12.16 – 26.02.17, with Saâdane Afif, Diego Tonus, Guillaume Bijl, Edith Dekyndt, Marilou van Lierop, Gabriel Kuri, Suchan Kinoshita, Fabio Zimbres, Javier Téllez and Latifa Echakhch.

(Image on top: Rosa Barba, Outwardly from the Earth’s Center, 2007. Film still © Rosa Barba, courtesy the artist)

- From the issue: 81

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Claire Le Restif, Bouchra Khalili, Sophie Legrandjacques, Sophie Lévy, Christine Macel,

Related articles

Céline Poulin

by Andréanne Béguin

Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Interview with Warren Neidich

by Yves Citton