Protective Body

fashion and social struggles

Can spheres as contradictory as fashion and social protest find a meeting point? Logic would have it that they cannot, because one contradicts, rejects and even scorns the other. Leaving aside the grotesque and misplaced forays made by certain fashion designers into revolutionary imagery, haute couture does not go so far as to support or take part in social struggles. Yet the current interest shown by creative areas in the culture of the 1990s seems to provide an entry point which might well relativize this situation.

Bernadette Corporation, extrait de / from Is Everybody on the Floor, 2009, impression jet d’encre / inkjet print. Courtesy Bernadette Corporation ; Greene Naftali, New York.

From ready-to-wear collections to musical tastes, by way of references made by artists and exhibitions, the 1990s worked their way deep into the renewal of forms and ideas. Because we cannot draw up an exhaustive inventory of this phenomenon here, let is dwell on one or two examples which illustrate this keen interest, as well as a certain connivance with social struggles. Recently, and on two occasions,1 Willem de Rooij exhibited strange installations consisting of mannequins clad in tracksuits, placed on pedestals, asserting their role as displays for department stores. Collected by the artist, this series of clothing—which he titled Fong Leng, after the name of the Chinese-Dutch fashion designer who designed and manufactured it between 1985 and 1995, with the goal of making her production more democratic—powerfully evokes the streetwear fashion of the 1990s, whose forms and textiles are today intermingled with those adopted by 12-45 year olds. In addition to the very seductive radical chic of these installations wildly imitating the displays of major ready-to-wear brands, it is more the notions of mass production, pernicious seduction and modifications to the appearance of bodies in the media regime that are revealed by these disquieting anthropomorphic presences, devoid of any substance. A few years earlier, de Rooij produced the series of collages Index: Riots, Protest, Mourning and Commemoration (as represented in newspapers, January 2000-July 2002), presenting images of protesters at large social gatherings, clipped from the press. With neither captions nor re-contextualization, these compositions reveal the repetition and exhaustion of the subject by media organs making the reader insensitive to this type of iconography. If this over-production stifles messages, what remains, if not our own body, to convey information? Installed close to each other at the MMK, these two propositions prompted people to rethink the relation between fashion and social movements and thereby reconsider the political potential of clothing as a medium.

Bernadette Corporation, Get Rid of Yourself, 2003, vidéo, 61’. Courtesy Bernadette Corporation ; Greene Naftali, New York.

The activities of Bernadette Corporation have also been re-interpreted in recent years, something which founder-member John Kelsey has ironically described as “1990s’ fetishization”.2 As a collective with many different identities, founded in the early 1990s in New York, and inspired in equal measure by the Situationists, Godard’s “Dziga Vertov” period and by Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm Mclaren, Bernadette Corporation commenced its activities by designing women’s lines combining streetwear and DIY haute couture,3 whose sense was directly created by their style. In 2009, their project The Complete Poem included individual and group portraits appropriating the codes of fashion photography and, more specifically, those of Calvin Klein’s advertising campaigns of the 1990s, photographed by Steven Meisel, whose sober, all black-and-white aesthetic became iconic—and thus appropriatable—and is very in vogue these days, especially in the “Normcore” trend, and crops up, for example, in the portraits of Talia Chetrit, Josephine Pryde and in Timur Si-Qin’s series In Memoriam (2014).

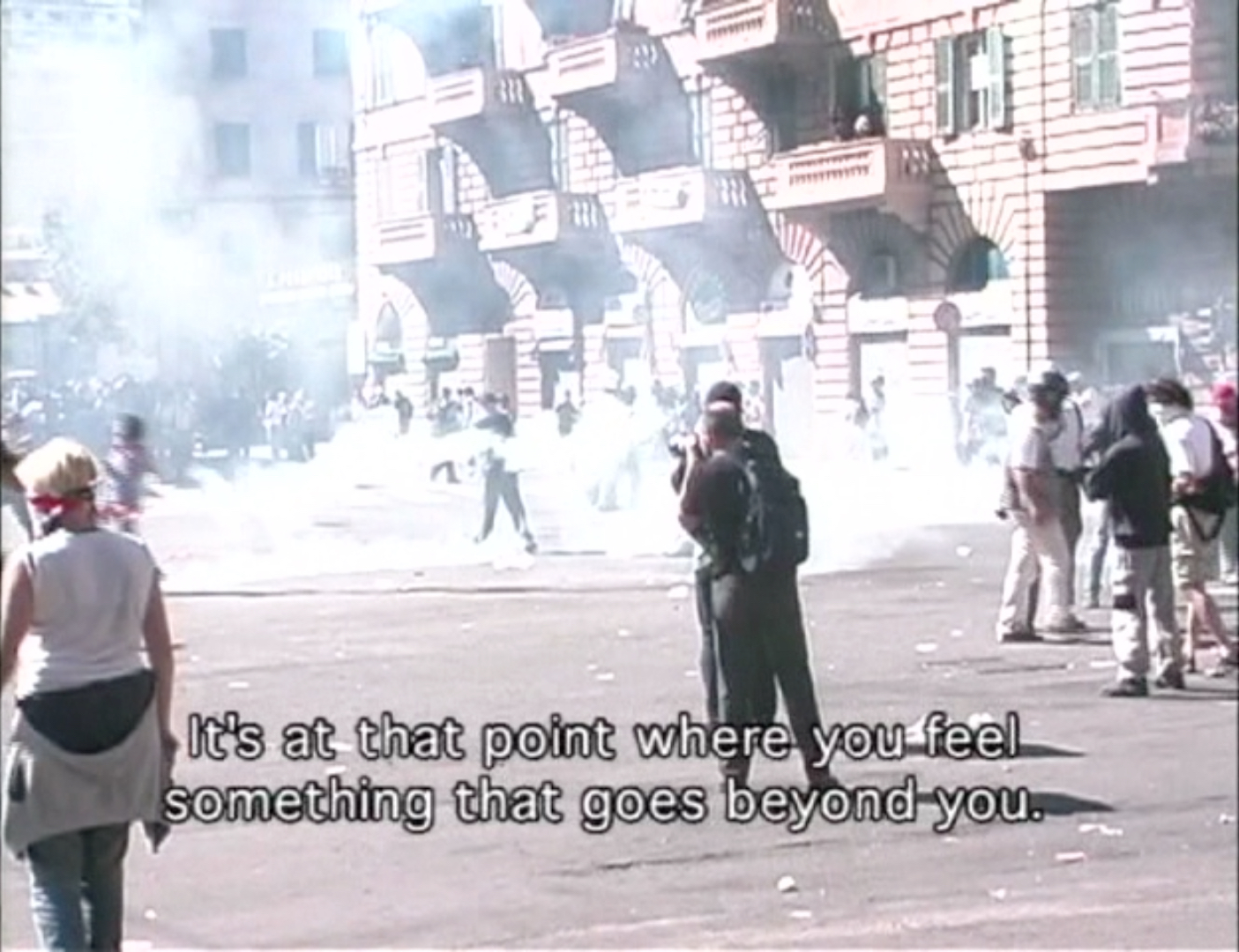

Membres du Black Bloc utilisant des fumigènes et s’équipant pour affronter la police / Black Bloc members using smoke bombs and equiping themselves before clashing with police. Paris, 28.04.2016. Photo : Pierre Gautheron / Hans Lucas.

The attention paid by Bernadette Corporation (hereinafter BC) to political struggle was confirmed when the collective joined forces with the Imaginary Party (a faction of post-Situationist activists and intellectuals) to make the film Get Rid of Yourself (2001-2003) during the G8 meeting in Genoa in 2001, probably one of the most violently repressed anti-globalist gatherings history. In this instance, BC relied on the reports of Black Blocs and pictures of their clashes with the police. Appearing in West Berlin in the early 1980s as part of the anti-nuclear movements, and given plenty of media coverage ever since the WTO summit in Seattle in 1999, the Black Bloc movement is above all a protective tactic against police repression during large popular uprisings. It is part and parcel of the anarchist tradition of direct action, and refuses any kind of political affiliation. The Black Bloc is “an aesthetically very distinctive technique”, as the political scientist Francis Dupuis-Déri5 has explained many times over: clad in black to preserve their anonymity, those forming a Black Bloc wear functional clothing (scarves, balaclavas, hoodies, sneakers, combat boots, jeans and track suits) and protective items (helmets, gas masks, shin-guards, elbow pads, gloves) to parry police attacks (using gas, tear-gas, truncheon charges…). The result of this “protective DIY” is an unexpected resemblance to the police, which puts both sides on an equal footing: homogenization does not occur only on the police side (their uniform) but also on the Black Bloc side (adopting an appropriate outfit), thus giving the impression that one army is confronting another, and transforming the street into an off-the-cuff battlefield. As a kind of false documentary about the Black Bloc parodying the film tract genre, Get Rid of Yourself overlays the 9/11 attacks, a G8 summit meeting, Chloë Sevigny and Chanel models, and creates an opaque idea rivalled only by the doubt and confusion of a new youth unable to set up a political alternative. By associating two seemingly incompatible phenomena, the BC approach seems, in spite of everything, to underscore the political potential of fashion, at work today in the spirit of brands such as “Vêtement” and “69”, and in the editorial policy of the magazine Girls Like Us. This relation is further corroborated by a trend in present-day fashion known as “Health Goth”, showing surprising similarities with the gear used by the Black Blocs. Identified in about 2014, this trend asserts a post-gender attitude that is biotechnological, wholesome, and sporty, and blossoming in a present period regarded as dystopian. Its outfits draw inspiration from the sportswear of the 1990s, from security clothing, from combat and protective clothing, and from the SM style, and encourage the monochrome (often black and white), ushering in a sort of Gothic 2.0. In the wake of designers like Rick Owens and Hood By Air, we also find this tendency in the work of Alexander Wang, Nasir Mazhar, Craig Green and Liam Hodges. As with the Black Bloc, the Health Goth style absorbs the sartorial codes of the police (riot police and special crack units) and lends those sporting them the look of urban soldiers. Spread through public places, this trend might be likened to a multiple contingent, dispersed and out of control,6 constantly ready for a fight: with all due respect to Walter Benjamin, fashion is thus separated, if only for a period of time, from its links with capitalism, by way of a sartorial style at once giving rise to forms and apt for insurrection.

Claire Fontaine, Anonymous, 2016, courtesy Claire Fontaine ; Galerie T293, Rome. Photo : Roberto Apa.

Isa Genzken, Untitled, 2015. Courtesy David Zwirner ; Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn ; Adagp, Paris.

This relation between fashion and social struggles is also explicit in the recent proposals made by artists aware of the latest political turns. Accustomed to this, the collective artist Claire Fontaine recently presented a mannequin bedecked with the sartorial attributes of the Black Blocs, clutching a tear-gas grenade and wearing the mask of the Anonymous. Shown at the Museo Pietro Canonica in Rome among copies of ancient sculptures, this installation associated Graeco-Roman statuary, a display stand for fashion items, and an urban guerilla emblem, thus creating a possibly slightly simplistic parallel with the current protests of anti-EU demonstrators in Athens. In a more enigmatic vein, since 2013 Isa Genzken has been developing a series called Schauspieler (Actors), groups of models decked out in clothing as brightly coloured as it is eccentric, conjuring up an agora wavering between order and chaos. Among them, some wear helmets and black streetwear clothes, protective gear and oxygen masks, while others are clad in police uniforms. Genzken here arranges a strange procession, certainly not without wit, but whose eccentricity in terms of colours and forms spreads a feeling of anxiety about the intensions of these people: what do they signify? What are their codes? There are no answers, with the result that their placidness seems to harbinger a sudden and violent uprising. If Benjamin Buchloh here perceives individuals whose extremely heterogeneous props confirm the homogeneity of their condition as mass consumers7—and thus their powerlessness in the face of a neo-liberal economy—,we note, on the other hand, that in their presence, the visitor finds him/herself in the thick of a disconcerting gathering which may implode at any moment, like local residents and pedestrians finding themselves, despite themselves, onlookers witnessing violent clashes between Black Blocs and the forces of law and order.

Isa Genzken, vue d’exposition / installation view, Museum der Moderne, Salzburg, 2014. Photo : Rainer Iglar © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn ; Adagp, Paris.

This analysis of the group is also to be found at the heart of Anne Imhof’s performances/installations, such as Faust, presented at the German pavilion in the latest Venice Biennale. There is much to say about this work, but let us focus here on this horde of sickly young people, wearing dark and often well-worn clothes (a mixture of Normcore and Health Goth styles), who are asked to be themselves, even though while performing a series of gestures and movements which, from time to time, take them out of their lethargy. If Anne Imhof does not establish any distance between performers and visitors (these latter being at the heart of different actions), she presents an imminent danger, giving rise to tension and anxiety in spectators who, tempted by their peeping-tom instinct, remain fearful about what they are being presented with. Here again, it is hard not to read Faust as an allusion to the Black Blocs, with its black-clad, balaclava’d performers, wearing knee pads, setting fire to things, simulating combat as if in an urban guerilla situation, stopping and starting again in an impromptu way, but never making any identifiable claims. Very much of their time, they represent a youth that has gone beyond its status of malleable victims of fashion-branding, and is using its appearance as a political body/image: “At any moment they seem on the point of being turned into a consumable image and yet their subjectivity is waging a constant war against their own commodification and reification.”8

Eliza Douglas, Lea Welsch, Billy Bultheel dans / in Anne Imhof, Faust, 2017. Pavillon allemand, 57e Biennale internationale d’art contemporain, Venise / German Pavilion, 57th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia. Courtesy Anne Imhof. Photo : Nadine Fraczkowski.

Stine Omar dans / in Anne Imhof, Faust, 2017. Pavillon allemand, 57e Biennale internationale d’art contemporain, Venise / German Pavilion, 57th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia. Courtesy Anne Imhof. Photo : Nadine Fraczkowski.

Despite its declared vision of the soft fascism at work in our techno-neo-liberal societies, as much in its treatment of bodies as in its presentation of a society of ubiquitous control, Faust does not manage to get beyond a worrying aestheticization of violence (present among many contemporary artists) and contributes to its normalization. What this aesthetic reveals, or at least confirms, is the way in which war is henceforth no longer confined to the battlefield, but acts at the very core of our lives by becoming involved in our daily round. Including in our bodies and our privacy, like a bio-power acting without any prior statement at any moment whatsoever, by way of physical and armed conflicts, but also through psychological and competitive clashes. By being thus rendered commonplace, violence and war are part of self-construction, and turn us into beings called upon to learn how to defend ourselves: a future full of combat which is gradually being imposed on all and sundry. Instead of learning how to make peace.

My thanks to the artists Ellie de Verdier and Benjamin Collet for their advice and suggestions.

1 At the Consortium in Dijon in 2015 and at the MMK in Frankfurt en 2016.

2 https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/mar/24/bernadette-corporation-ica

3 “Techniques of Today – Bennett Simpson on Bernadette Corporation” in Artforum, September 2004.

4 On this see the film Diaz: Don’t Clean Up This Blood (2012) by Daniele Vicari.

5 Francis Dupuis-Déri, Les Black Blocs, la liberté et l’égalité se manifestent, Collection Instinct de liberté, Lux Editeur, Montreal, 2016.

6 Already to be found in the methods of Daech.

7 Die Ready Made Figure Sculpture, lecture given by Benjamin Buchloh at the MMK in Frankfurt (2015), which can be listened to at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m2I6Gm5qufI

8 Interview with Susanne Pfeffer conducted by Noemi Smolik, which may be read at: http://moussemagazine.it/anne-imhof-faust-german-pavilion-venice-biennale-2017/

(Image on top: Willem de Rooij, The Impassioned No, 2015, Le Consortium, Dijon. Photo : André Morin.)

- From the issue: 83

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Everybody in the place. Clubbing as an antidote to the contemporary art institution?, Post Human,

Related articles

The World Through AI

by Warren Neidich

Paris noir

by Salomé Schlappi

Some white on the map

by Guillaume Gesvret