Géraldine Gourbe

Géraldine Gourbe talks to Clémence Agnez

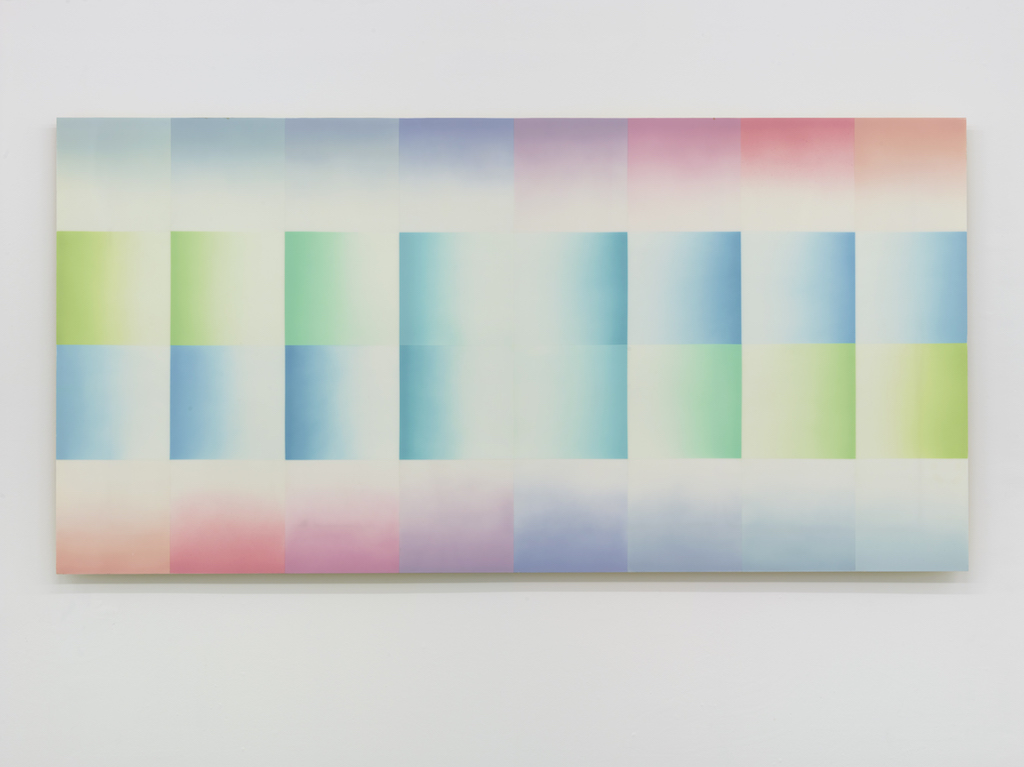

The Géraldine Gourbe exhibition about Judy Chicago’s œuvre deals mainly with her youthful work, paying special attention to the works produced when she arrived in California. Focusing on the twofold influence of both Los Angeles and a certain number of young artists associated with the emerging Finish Fetish tendency, Géraldine Gourbe offers us a new narrative about the way Judy Chicago’s work developed, caught as it was between the hedonistic celebration of the Cool School and the conspicuously intellectualized austerity of Minimal Art. Minimalism was the fief almost exclusively of male figures, and very largely dominated the East coast art scene which, at the turn of the 1960s, provided the tone for the whole of America’s art output, asserting itself in those years as the canonical formula for the history of western art then being written. Judy Chicago espoused its codes in the early days of her œuvre, but she had trouble earning the same recognition as her male peers and, as soon as she arrived in Los Angeles, she crossed her minimal forms with a pop and overtly sensualist touch. Géraldine Gourbe talks to us about that moment of formal re-semanticization when she introduces us to the artist’s youthful works. Halfway between the East and West coasts, and between Minimalism and the Cool School, the works on view in the exhibition are also being shown, at times in a convergent way, at others in a differential way, together with several artists active around Judy Chicago in the same period.

Even before you introduce Judy Chicago’s work, you present it in the exhibition by mooring it to California. With an awareness of the state’s specific features—topological (vast landscapes, unchanging climate), industrial (many aeronautical and armament production sites, with a predominance of new plastic and synthetic materials) and artistic (the emergence of the LA/NYC rivalry and the individuation of two schools referred to back-to-back)—, you propose a new point of entry to Judy Chicago’s œuvre, included in that cultural and territorial dialectic between the two American coasts rather than in just the assertion of her political and in particular feminist commitment. Why did you choose to put this geographical fact at the centre of the show?

Since I started work on my thesis in 2002, I’ve been travelling around Los Angeles and then Southern California—I’ve gradually left the chilly rooms of the Getty Research Center for studios and non-profit spaces, thanks to the energy and knowledge of the curator Isabelle Le Normand. Like all Europeans, at the outset I was fascinated by a certain “otherness” about Los Angeles, its dimension as an American city per se, as is well described by the brilliant Reyner Banham in Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles, a very 1970s documentary produced by the BBC.

Then, little by little, as I worked on my book In the Canyon, Revise the Canon, I came to the realization that LA has had a certain counter-cultural history ever since the beginning of the 20th century—prehistory for Californians!—, deeply imbued with the German Lebensreform. A somewhat German libertarian, pacifist and collectivist movement—very influential at Monte Verita for example—which spawned a ‘nature boys’ trend from Santa Barbara to San Diego… That was a shock! I wanted to twist the narrative about the Californian scene of the very Finish Fetish 1960s, and present another, not out of a spirit of contradiction, or wishing to replace one historiography by another, but in order to show the plurality of viewpoints. This comes from my feminist and anti-racist education, with a keen eye on the standpoint, and where the various viewpoints are situated—starting with my own. I refer a great deal to Michel de Certeau, a pioneer on this subject—and at the root of cultural studies, something that can’t be said enough: “Believing doesn’t mean putting your hand on something, it means being implicitly marked”. I think that was my way of putting on an exhibition based on the history of ideas—I studied political philosophy at Paris X-Nanterre—and not on a conception of art history as taught to museum curators and certain exhibition curators.

It enabled me to introduce contradiction into our systems of reflection and fantasies: and California has plenty of them, they’re also its stock in trade! LA’s number one industry—entertainment—understood it a long time ago. And I also like this aspect of LA, the fact that it is still feeding my imagination…

This plural knowledge enabled me to twist another major principle of history writing, which the art historian Linda Nochlin has made us aware of: artistic genius. It was clear that Judy Chicago’s career in LA (in the 1980s she went to live in New Mexico, like other artists and art critics) has been much less linear and thus more complex with regard to this plural genealogy I’ve just mentioned.

The establishment of those libertarian communities you describe might seem like a late repetition of the various 19th century utopian projects, which saw Marxist- and anarchist-inspired European communities establishing themselves on American soil, to found and experiment with the innovative social forms of organization that they imagined. Did Judy Chicago have any historical or even practical knowledge of this type of programme, prior to settling in California?

Judy discovered my idea and the Nature Boys the day before the show’s opening. She also knew nothing about the films of Pat O’Neill, that she adored. We had decided that she would concentrate on this novel re-creation of Feather Room (1965-2018), for which there was just one photo, one document. With the architect Axel Clisson (Socle studio) and Judy, we re-thought the whole procedure and today I’m proud that that impulse stimulated other American institutions and the art market (Feather Room will be re-assembled at Jeffrey Deitch in LA in September 2020). As I said, it seems to me important today to write an art history that is made more complex by a history of ideas. This gives some breadth to monographs of artists which can themselves have light shed on them through other artists’ works. Here I also wanted to show the density of minimalist forms, European abstraction, Pop, sculpture and the relation to the game board (or model) in Judy’s work, random procedures, surroundings, landscape, evanescent Land Art, psychedelic art, the backlash of conservative American culture.

You describe the exhibition as “monographic and collective”. This declaration, which might seem paradoxical, seems to me, on the contrary, to be the symptom of an especially meaningful choice: it asserts the need to pass by way of a consideration of a plural off-screen factor in order to properly grasp an individual artistic production. As well as being a point of critical method which challenges the autonomy of the subject it is examining in favour of a collective perspective, this twofold description is all the more illuminating in the very specific case of Judy Chicago’s work because it echoes the inclusive methods often going on in it. Could you tell us a bit more about these back-and-forth positions between individual and collective? Can we think of these two elements, which co-exist in her work in that period, together, namely, on the one hand, the deconstruction of the spirit of seriousness and the monumentality of minimal art, and, on the other, the eruption of the collective?

In 2007, I submitted my thesis which in particular used as case studies the Womanhouse and the Women’s Building initiated by Judy Chicago. At the time, I had the impression of crying in the wilderness, a bit like those Nature Boys, especially William Pester who walked about in the desert barefoot in the 1910s and 1920s… And then I would say, slightly before Mousse’s last publishing on the artist as curator1, that the Womanhouse became an icon and that it’s as if the whole of Judy Chicago’s work could be summed up in it, or worse still in that feminist history. An excessive compensation, in a way, to the detriment of those magnificent works of the 1960s produced under her first artist’s name, Judy Gerovitz, which I discovered in the brilliant first version of “Pacific Standard Time” in 2012 in Los Angeles.

Eric Mangion, and then Jean-Pierre Simon of the Villa Arson were very touched by that history—as was the late lamented Xavier Douroux, and his extremely brilliant associate Géraldine Minet, with whom we were meant to show that exhibition at Le Consortium in Dijon. It was a way of paying tribute to him for everything he initiated around counter-cultures and Californian art, and his both kindly and head-on support (Xavier, right!) for what I was doing, but which I still didn’t have confidence in. On this point, Xavier was a feminist. Precisely where the Nice show is wrong about him is when it shows that Judy Chicago is NOT a cameo role but a visionary. During an architectural project for The Dinner Party (1974-79) —a permanent housing for Dinner Party—she coined a slogan which I love: Sustain the Vision. We find this research and these silkscreen works in the upcoming publication we’re preparing jointly with the Villa Arson and Shelter Press (the publishers of In the Canyon) which follows the show: neither a catalogue, nor an essay, a bit of both while also being something else: we’re very excited, Judy, her studio, Eric Mangion, Céline Chazaviel, Shelter Press and myself.

To get back to your question, it seemed to me that the only way of really shedding light—in an obvious way—on this minimalist work of Judy Chicago was to associate her with other artists of her period. Close to her, or not. The interplay of contrasts plays the same critical role as that of the interplay of affinities. Unlike her cult autobiography Through the Flower, translated by Sophie Tame from Nice, a former student at the Villa Arson, prefaced by myself, and published by Les Presses du Réel—again in cahoots with Xavier!

The hanging in the first room of Marcia Hafif’s never exhibited first drawings—we framed them for the first time!—and Judy Chicago’s first silkscreen works helped me to realize to what point the European language of abstraction was at the root of North-American Pop art. It’s the type of revelation that permits an exhibition, and re-writing a history of art can only be done with several characters. I wanted to tell a story, and the main theme of Judy Chicago’s œuvre enabled me to do it. Furthermore, that very explicit first room posits from the outset the sensualist, not to say libidinal vision of those very young artists from the early 1960s, who are all icons today.

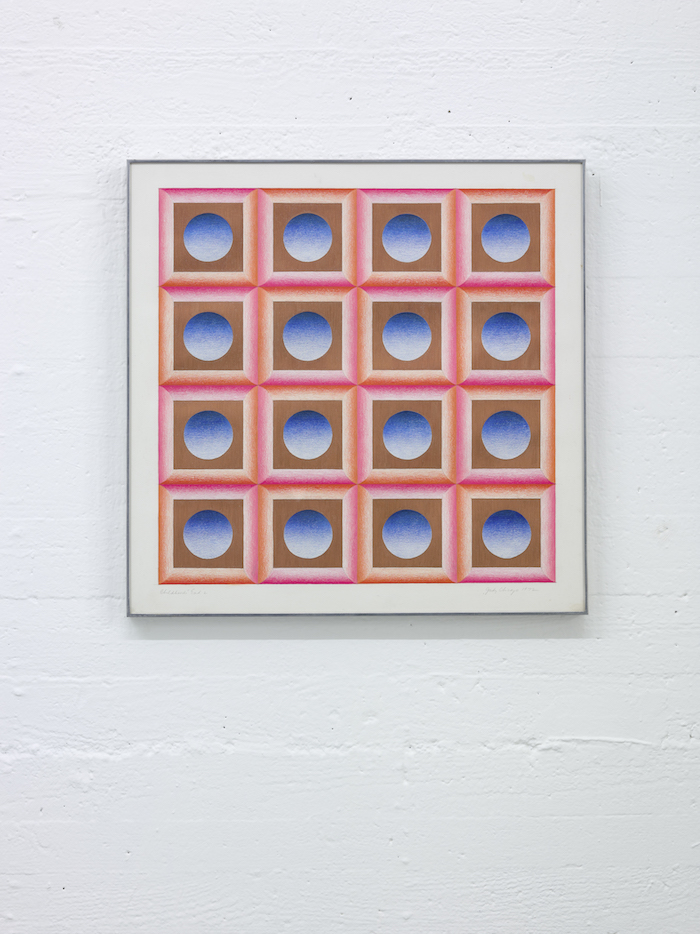

In fact the inclusion in the exhibition of Marcia Hafif’s drawings leads us right away to a watershed between abstraction and Pop proto-semantics, with forms which load the minimalist geometry of the—still shy—luxuriance of the mandala and the impact of the logo. We find this transitional effect again in the following room opposite Judy Chicago’s famous Hoods. How are we to understand this slightly paradoxical dialectic between the re-appropriation of industrial signs in the process of being mass-produced at the turn of the 1960s, and the appearance of New Age markers?

Some people see Navajo forms in them, those native Americans living in New Mexico where Judy has been living for 30 years. The convergence is quite appropriate (even though I wouldn’t talk about New Age, it’s very materialistic, Judy’s work, and not very spiritual), but I’d rather refer to hippie forms. Just as using drugs went hand-in-hand with a certain exultation (rather than liberation) of bodies, and also took part in endangering the patriarchy. This is a viewpoint that still hasn’t been studied much in gender-queer studies.

In the light both of her autobiography—which you’ve just prefaced for its first edition in French—and the exhibition “Los Angeles, The Cool Years”, one gets the feeling that Judy Chicago has a relation to her work that’s governed by the assertion of the pleasure principle, visual enjoyment, and a certain playful and liberating spontaneity. Might we see here the ferment of the path she’s following by gradually separating herself from the great canons of minimal art?

Today, Judy Chicago still has in her office a very beautiful photographic portrait of Anaïs Nin, who also prefaced her book Through the Flower. She still describes her as her mentor; this is what I like about Judy, there’s a loyalty to her tribe and to the women and men who’ve mattered for her. This is why life in the Belen studio (New Mexico) is very joyful, even if the town is quite “white trash”.

The pleasure obtained by the fact of making love is a constant feature associated with the vitalism which hallmarks Judy’s life and work, and which she deals with at some length in her autobiography. Today it is still very present in her words, her thoughts, and her love life with her husband. Her works, displayed on the walls of the old pioneers’ hotel in Belen, are quite clear about this! This is, and has been, her source of emancipation. Assuming the fantasies and forms of pleasure was part of her self-assertiveness as an artist, and this was prior to the arrival of the women’s liberation movement. It was inconceivable that that sensualist part of her life should be put to rest for work reasons or, worse still, for moral reasons during the 1960s (one thinks of the Mad Men series, a fiction illustrating the suffocating condition of women in those years). The pornographic visual culture has also been very present in the work of other Californian artists contemporary with Judy (a little older these days, and some of them dead). I’m thinking of Craig Kauffman, for example. We still don’t know his work very well in Europe, which I find a pity.

1 The last booklet in the series The Artist as Curator, devoted to the figure of the artist-cum-exhibition curator: “Womanhouse”, 1972, by Judy Chicago, a supplement in Mousse n° 51 – 1985-1995 Exhibitions Views, 2015, les presses du réel.

Image on top: Judy Chicago, Feather Room, 1967-2018. In situ installation, scenography: Socle, New York. Production: Villa Arson, Nice ; Salon 94, New York. Courtesy Judy Chicago ; Salon 94, New York.

“Los Angeles, The Cool Years” with Marcia Hafif, John McCracken, Robert Morris, Bruce Nauman, Pat O’Neill and DeWain Valentine, curated by: Géraldine Gourbe, Villa Arson, Nice, from July 1st to Nov. 4 2018.

- From the issue: 88

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Anna Longo, Patrice Maniglier, Catherine Malabou, Nicolas Bourriaud,

Related articles

Céline Poulin

by Andréanne Béguin

Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Interview with Warren Neidich

by Yves Citton