Pieter Vermeersch

Pieter Vermeersch likes defining his monochrome paintings as “as an end of linguistic articulation”.1 This is probably why handing yourself over to a critique of your work is far from being an easy thing to do. In Vermeersch’s pictorial world, all theoretical discourse is in fact brought to its degree zero. As he mentions on several occasions, his main concern is to confront the very essence of painting.2 Talking about his approach, he makes reference to a series of eight small pictures (8 Paintings, 1999) which he regards as a manifesto, and are on view in the entrance to the first major solo show which the M-Museum in Louvain is devoting to his work. Each picture represents the same ordinary and misty image of a windscreen and a windscreen-wiper photographed by the artist. What interests Vermeersch is the act of mechanical and objective reproduction of this image, which he paints in a repetitive and humdrum way. As he himself admits, this is a slightly “dogmatic” starting point, but one that is necessary to steer clear of the romantic illusion of the artist, tending to stir up emotions in the viewer’s soul.

The effects that his work is capable of creating in the onlooker’s mind are hardly taken into account in his artistic approach. His main aim is to manage to formulate a sort of New Objectivity, an impersonal and almost mathematical pictorial language. This does not prevent the spontaneity of the gesture from re-surfacing in this series of paintings which, despite their marked resemblance, are all different from one another. The more fiercely the painter perseveres in his task of identical reproduction, the more impossible the task turns out to be. If this series is fundamental for understanding the tension that runs through all of Vermeersch’s œuvre, caught between objectivity and subjectivity, and between level-headedness and impulsiveness, it also underpins his interest in the idea, stemming from the Renaissance, of the picture as an ideal and transparent window, open to the world. In 8 Paintings, the window remains a tangible and almost commonplace object, but, in Vermeersch’s later work, it takes on a more conceptual and metaphorical connotation. What interests the artist, and what he looks at through the windows in his painting, is not the world of objects and human beings, but the interstitial space between the two, the void which enables the solid to exist.

Among the great portraits in the history of art, Pieter Vermeersch is especially attracted by those in which figures seem to float in an indeterminate space, as in the works of Rembrandt, Goya, Velázquez and Manet. He photographed these pictures and repainted them, focusing solely on the empty backgrounds. By reversing the hierarchy between fore- and background, he turns these uninhabited spaces into the main object of his painting.

If portraits by old masters inspire some of his monochromes, it is the perimeter of his mobile screen that defines the frame’s content, where other canvases are concerned. In both cases, photography lies at the root of the chromatic abstraction within which the relation to the material world remains essential. So the series of resolutely abstract photographic works on view close to 8 Paintings tallies with the need to create a dialectic relation between reality and abstraction, two dimensions which Vermeersch is forever putting back-to-back. It is probably this rootedness in reality, conveyed by the photographic medium, that causes him to keep his distance from the work of painters like Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko, with which his œuvre has often been compared. Their abstraction, in the eyes of the Belgian artist, is too “subjective”, because it involves a metaphysical and spiritual dimension that he is trying to get away from. The aim of his hyper-realist abstraction—a label that has often been attached to his work—is to confront the onlooker with an objective, even prosaic space. When we look at the perfect gradations that have made him famous, we find not so much the image of a higher reality as that of a daily round transfigured by a poetry of colours and lights. In its complexity and its elusiveness, there is something that makes his work more accessible, all of a sudden: there is nothing to see or understand, there is no metaphysical dimension to flush out, but rather an aesthetic experience to be had.

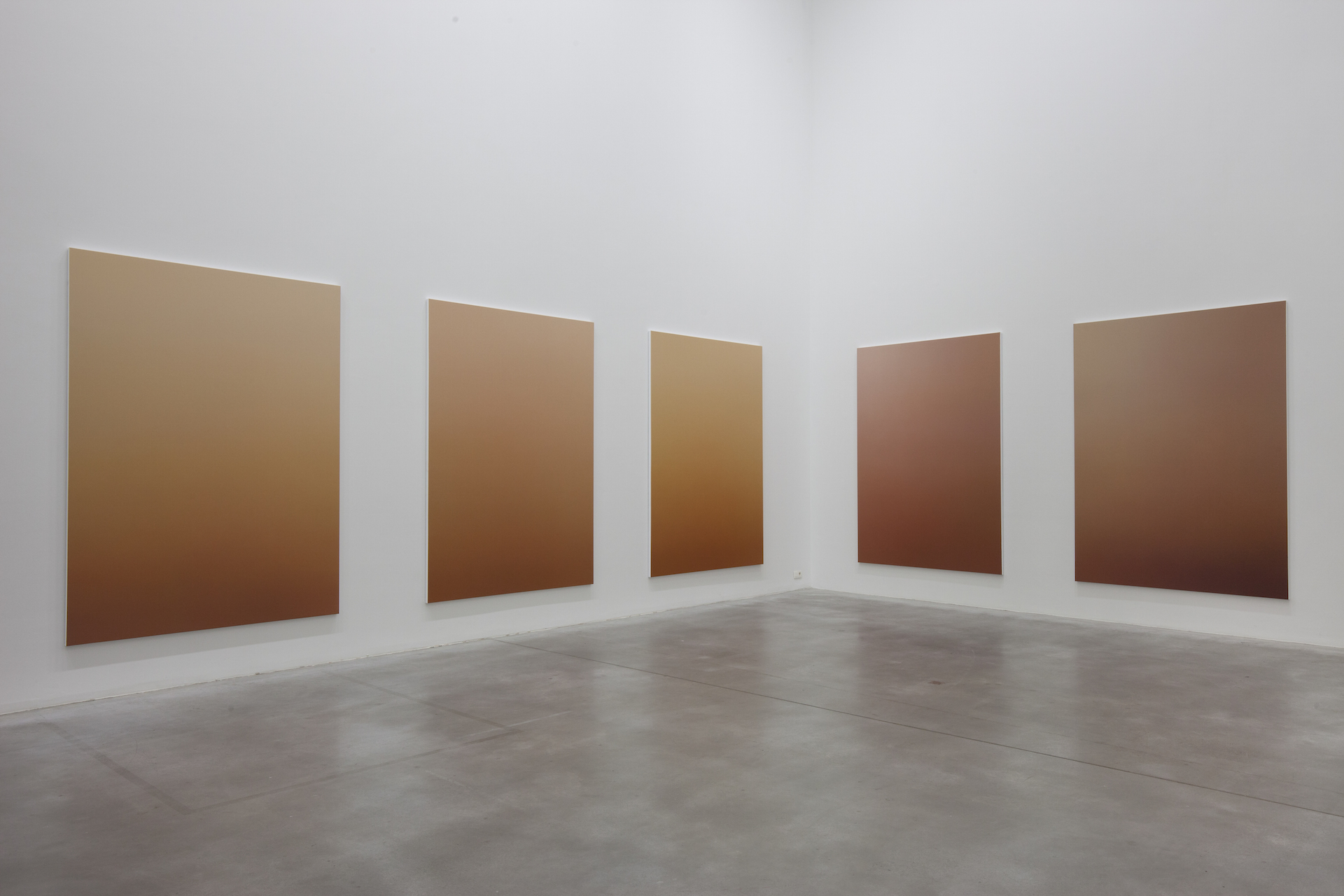

This is what is being offered by the solo show at the M-Museum, where Vermeersch does not restrict himself to a mere hanging of his pieces, but rather takes possession of the spaces by way of monumental architectural works and wall paintings made up of gradual transitions of colour. The first room, dominated by an all-encompassing colour which shifts imperceptibly from white to pink, is crossed by a rough-looking wall. This latter extends to the second room, creating a subtle dialogue with space which calls to mind Richard Serra’s minimalist sculptures. Throughout the visit, we are surrounded by other wall paintings, this time in blue and yellow hues. If, on the one hand, these monumental paintings refer to the idea of a slow and imperceptible flow of time, on the other they prevent the eye from settling on any specific point, by forcing it to move from one shade of colour to the next in a sort of endless and frenzied loop. The extremely subtle shift between the different shades of colour may seem to be the result of a spontaneous and intuitive gesture, even though it is the outcome of a very painstaking calculation. To produce these gradations, the surface has been divided into 130 colour fields, each one darker than the previous one. For Vermeersch, these paintings display the intent underlying his entire output: not so much focusing on one theme in particular, as on a specific modus operandi, which takes form in an almost mathematical approach to the construction of the image.

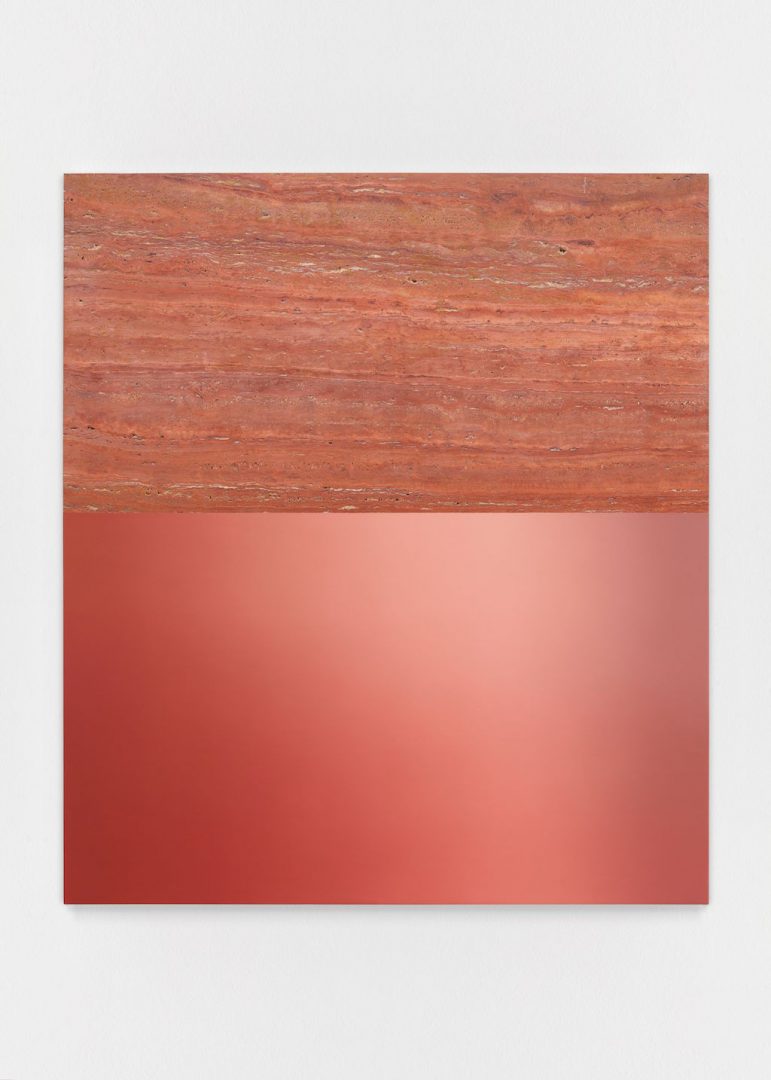

But despite the declared quest for a result devoid of any subjective component, the tension between objectivity and spontaneous gesture which informs the series of 8 Paintings re-appears in the works on marble and the scraped pictures we find in the remainder of the exhibition. The scratching of the picture here assumes monumental proportions, because Vermeersch becomes involved in a direct assault of the wall’s surface, entrusting to chance and gestural impulsiveness the task of creating a new and hitherto unseen form within the wall painting. Just as haphazard is the artist’s work on the series of marble surfaces which he started producing in 2014. Marble is a rock coming from age-old tectonic metamorphoses which define its complex weft, which is figuratively akin to that of a natural landscape. On such surfaces containing a temporal and cosmic dimension, Vermeersch adds a new layer, that of the present, made of finger-prints and fleeting brush strokes. So the artist’s ephemeral dimension is crystallized on a material which is above all a memory of extremely remote geological areas.

Running through all of Vermeersch’s œuvre, this contrast between an extremely objective attitude and a spontaneity that inevitably re-surfaces also finds its way into the onlooker’s perceptive experience. The almost mathematical perfection in the use of colours is just as undeniable as the overwhelming sensation it gives rise to, close to what Edmund Burke might have defined as the experience of the sublime:3 a sense of infiniteness, spatial and temporal alike, that grips us. The fact that Vermeersch considers this as an accidental gift coming from somewhere else and not from his own intent, does not take anything away from the sublime sensations we might feel. Vermeersch puts us opposite an infinite void, a void conjured up by the sculptures which wind up the M-Museum show. On the wall, three wooden stands show us their empty interior lined with precious metallic colours. They seem to be suggesting to us that the void is not just nothingness, but the thing that permits things to exist, based on a principle dear to oriental philosophy. As Zhuangzi, one of the fathers of Taoism, said: “The earth is certainly vast and broad, though a man uses no more of it than the area he puts his feet on.”4

1 Ed Schad, “Against the Void: the Work of Pieter Vermeersch”, in Pieter Vermeersch, Paris, dilecta, 2015, p.6.

2 “To bring the reality of light and color to life in the most basic possible way”, “Spontaneous Dogmatism”, Dieter Roelstraete interviews Pieter Vermeersch, in Work in Progress I > III, Paper Kunsthalle, 2005, https://www.pietervermeersch.be/texts.htm

3 Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, 1757.

4 Zhuangzi, the Zhuāngzǐ, circa 300 BCE.

Image on top: Pieter Vermeersch, Untitled, 2019. Oil on canvas, 230 × 170 cm (× 5). Courtesy galerie Greta Meert, Bruxelles / Brussels.

- From the issue: 90

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Caroline Mesquita, The Quistrebert Brothers,

Related articles

Gregory Sholette

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Vera Kox

by Mya Finbow

Fabrice Hyber

by Philippe Szechter