Sylvain Darrifourcq

If Sylvain Darrifourcq needs no introduction on the European improvised music scene—whether we have heard him play alongside the jazz eminences Joëlle Léandre, Michel Portal, Louis Sclavis or Émile Parisien with whose quartet he was awarded a “Victoire du Jazz” in 2009, or, more recently, explode alongside the prodigious members of the Tricollectif1 Roberto Negro and Valentin Ceccaldi, and in his own trios with the selfsame Valentin Ceccaldi and his brother Theo Ceccaldi under the name of IN LOVE WITH2 or with Valentin Ceccaldi and Xavier Camarasa in MILESDAVISQUINTET!3—it is more recently that he has appeared on the visual arts scene. After a collaboration between MILESDAVISQUINTET! and videographer Jean-Pascal Retel, notably presented at the 2017 Némo Biennale4, and a performance with Zimoun5 at the Kunsthaus Kule in Berlin at the end of 2018, he will soon premiere his first solo visual and sound creation, FIXIN6. For it, at a time when artificial intelligences are “trying” to compose music as well as humans, Sylvain Darrifourcq, percussionist and drummer, conceives his gesture as a click while submitting the machines to the individual will.

In addition to your collaborative projects, which are more expected for a musician, with choreographers and set designers, you do not hesitate to claim literary influences and perform with visual artists. In particular, you place the music of your trio IN LOVE WITH under the aegis of Faulkner and Beckett, within a certain non-linear geometry, in order to avoid, as you put it, “the arrival point”. What is behind this intent? If I had to summarize my current artistic concerns, I would say that I am trying to render a certain relationship to time geometric. Without wishing to reduce Faulkner’s writing to this dimension, his novels offer a very particular temporal experience (at least in his time), akin to deconstruction in The Sound and the Fury, and repetition in Absalom Absalom! But I could also mention Bill Viola’s work on slowness, to change the subject. Anything that emphasizes the subjective experience of time interests me, beyond aesthetics. But to work on this notion, I need to imagine it in a geometric way; for example, as a line that can be segmented at will. From this starting point, everything follows logically for an instrument like mine. Each impact could be a point, each rubbed sound, a segment, etc.

FIXIN is like a logical continuation of my work with MILESDAVISQUINTET!, which was a purely percussive form of music produced with a piano-cello-drums trio. For it, we refined our language to keep just polymetric pulsations, very mechanical things; which led us to make our gestures automatic.

What was a consequence of the MILESDAVISQUINTET! research thus formed the origin of FIXIN? I am really obsessed with mechanics, with playing like a computer, with acting like a computer, that is to say in an on/off way, relieved of everything that can be fleshy, human, of what I imagine as curves: it is the points, the straight lines, the sharp angles that interest me. As it happens, the software I work with, Ableton Live, works the same way. Visualization is only done through small squares, bars, lines, points… It is really a decomposition of time. All of this comes together for me: the way I see it, the way I write it, the way I think it and the way I see my body. The light system completes this, going in the same direction as a crisp geometry. The first light work that marked me was a piece by Philippe Parreno composed of about fifty neon lights placed in space whose sound, when they were switched on and off, created a real rhythmic piece. All these very rudimentary relations to information interest me.

On/off, binary, computer… All this makes perfect sense. Right. For MILESDAVISQUINTET!, we were three musicians at work on this and, to pursue the logic of spareness… I replaced the others with motors! (laughs) Then I discovered Zimoun’s work, which totally fascinated me. I contacted him, he was also impressed by what I was doing and we finally worked together last year. It was really when I saw what he was doing that everything came together and I began to fantasize about this kind of man-machine that performs FIXIN.

You describe FIXIN as an installation activated by a performance: the language here has clearly shifted to the visual arts… FIXIN is an intensely visual stage project. I am above all a musician, first of all an instrumentalist, and therefore pigeonholed as such; taking this step aside to propose a visual artwork meant finding partners and support. With MILESDAVISQUINTET!, we had already created a somewhat hybrid piece in collaboration with Jean-Pascal Retel who produced a visual adaptation of our music. A video projector connected to our instruments via sensors projected onto our bodies kinds of white pixels to the rhythm of our playing, or as a counterpoint, and these shapes revealed the set as the performance progressed. This project had been co-produced by Arcadi and presented at Némo, the Île-de-France digital arts biennale: it was at that moment that I felt that this step aside was becoming possible. And the more partners I brought together (in particular the Théâtre de Vanves, whose pioneering work I admire, the Cube-centre for digital creation in Issy-les-Moulineaux and the Muse en Circuit-national centre for musical creation in Alfortville), the more I was able to unleash my imagination and envisage an installation in which I would play. This process took about three years. Especially since I had never used computers for music. I started from scratch as far as this aspect was concerned and surrounded myself with fantastic engineers who are also, and even above all, artists: Nicolas Canot and Maxime Lance.

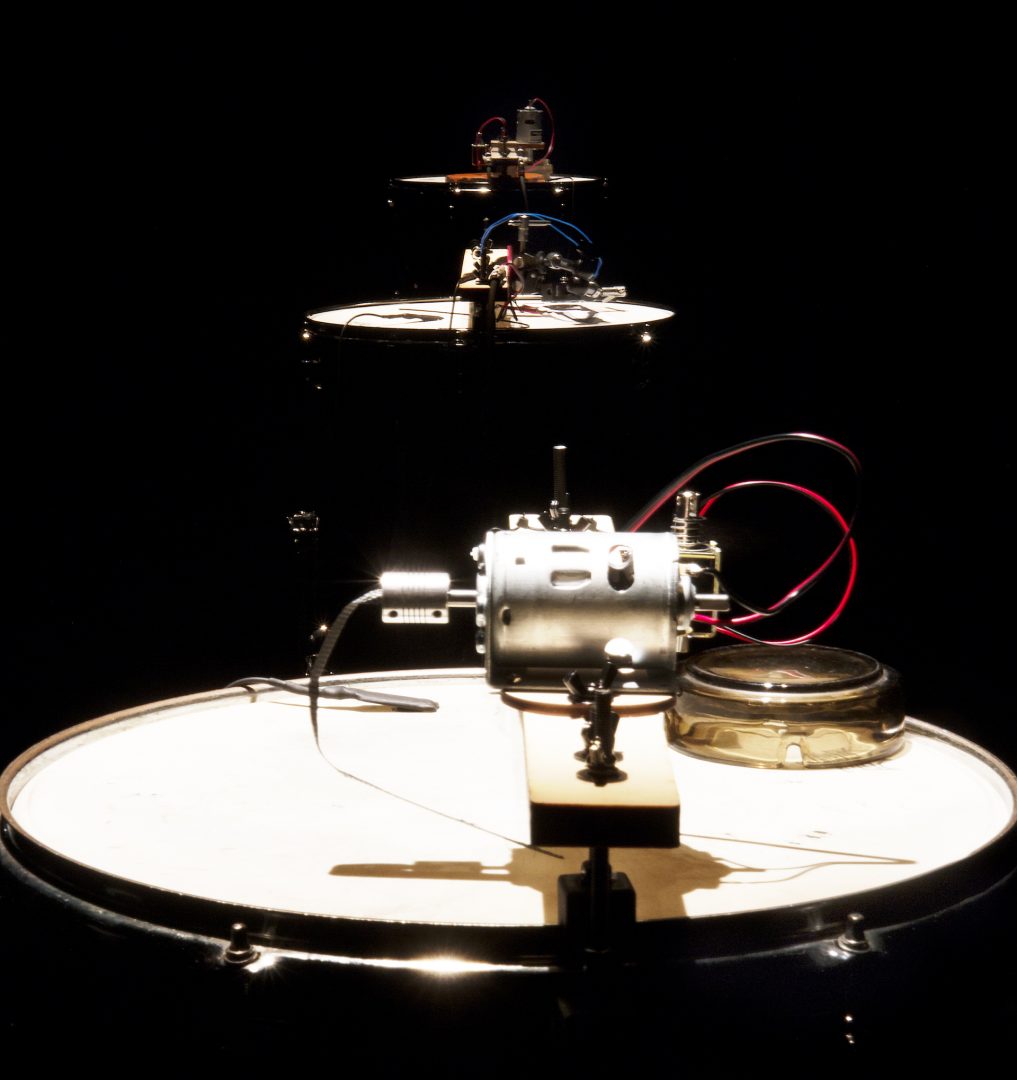

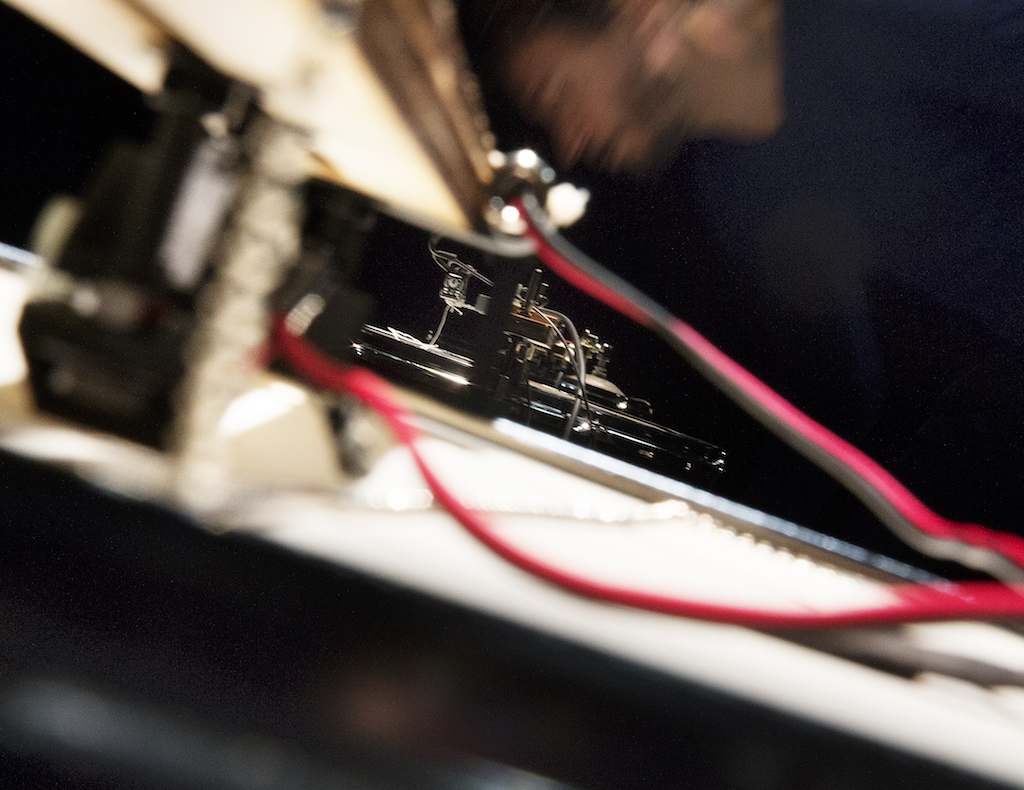

And so what is FIXIN, more precisely? Fixin is thus an immersive performance/installation in which a musician and a whole host of motors mounted on tom drums interact. The device—a kind of extension of my instrument (itself hidden) designed to be surrounded by the audience—is relayed by lighting that hides/reveals/dialogues in counterpoint. The music is minimalist and industrial. It is a question of testing the musician in his humanity. To what extent can man turn himself into a machine? What is the influence of one on the other? As I said, to compose, I use Abelton Live which is a software that allows me to send MIDI signals in a box—specially designed by Max Lance—which processes the information and transmits it to the motors. It integrates a Teensy microcontroller card (quite like the Arduino), transformers (MOSFET), power supply, USB, Ethernet connections, etc. I chose the motors (solenoids, vibrators, DC motors, motorized fader, electromagnet…) based on the types of sounds I had in mind, and all the objects on the drums are objects that I use in my regular drumming practice (steel egg cups, small sex toy motors, the most diverse found objects). This is where the game of going back and forth with the machine begins. After years of working to force my body and my musical gestures to become mechanical, I program these motors so that they mimic those “rehabilitated” gestures. They return to the sender in a way, but loaded with specific human phenomena (micro errors, irregularities, and so on). For me, it’s an incredible feeling. I can modify the speed and a raft of parameters. The fader for example… It’s a mixer controller mounted upside down, a rather fragile object, full of small notches inside, it’s the most complex object here. I attached sandpaper to it and it opens up so many sound possibilities depending on the object that I make it rub! By attracting the ball-bearings, the electromagnet produces a kind of acoustic granular synthesis: it turns on, it turns off, the ball-bearings stick to it and detach themselves permanently from it; here again, it is an on/off relation. There are also the vibrators that I use like basslines. There are many relationships to explore between them: the strength I give them, the tension of the skin above, the tension of the skin below and the acoustics of the room. And it’s different every time because the frequencies that resonate naturally in a place are never the same.

And everything will be visible, there will be no box or anything to hide all this? At first I thought about that but since the objects added onto the tom drums are the ones I usually practice with, they can’t be too clean. It had to remain coherent, the installation part cannot be too sleek in relation to the drum set I will play on, otherwise I will be excluded from it, and the installation is really like a visual extension of my instrument but also of my body and my intentions. I will be in the dark, and sometimes lit. My gesture really starts and stops like a click, it has no evolving dimension. It is a minimalist approach, after years spent gathering technique, to remove harmony, to remove melody, to remove everything that would be the flesh of music to return to its fundamentals, i. e. the emission of an on/off frequency, and to remake music with that. It’s really complicated because you have to get rid of everything you’ve learned.

It’s a Picasso style approach, this unlearning. That’s absolutely right. I learned music through written music and, when I discovered free improvised music, it was already a way to unlearn what I had learned.

You haven’t always been a drummer… I studied classical percussion, it’s a pretty wide field that includes keyboards, timpani, vibraphones, all forms of orchestral percussion—I played in an orchestra for a long time then I specialized in drums when I was seventeen. Improvised music came next. I discovered jazz, then really abstract music later on, and I became interested in each field with the same dogmatic approach: deconstructing, rebuilding, getting things out of it and then moving away from all these dogmas, so now I’m starting a new cycle again. But it’s very natural because this project perfectly matches my instrumental practice which was already stripped down.

So you were talking about “playing like a computer”: is automating your body a purely aesthetic aim, a physical performance, or is there a more conceptual, even political dimension to this idea? I am thinking in particular of the studies of the Gilbreths’ human movements—to take a pioneering example from this field—, of their division of workers’ gestures into combinations of simpler movements, of all these questions of optimization applied to industrial management… I read a lot of sociology and cognitive sciences, research that cuts across economics, statistics and cognitive psychology, especially in the field of rationality as a decision-making factor. What is the reason for a decision? Why is this decision made though it is on the face of it irrational? What cognitive bias is at work at that time? All this certainly echoes my practice as an improviser where it is a question of making decisions and acting in real time, even if things are perhaps less transparent in my head than my way of putting it here. But, at the same time, I am also interested in more coercive and deterministic theories. To understand a theory, I need to understand the field in which it is situated and contradiction seems to me to be the appropriate way. These readings are intended to complete a field of knowledge rather than to maintain my prejudices, particularly the political and sociological ones. Similarly, my artistic research is purely speculative. I do not give an answer, I do not position myself politically, I propose an aesthetic object that participates in man/machine questioning. I leave it up to everyone to get what they need from it. The next step for me would be to work with scientists. For the moment, I apply my ideas to motors and I’m starting to work with choreographers on these same themes. In particular, I am starting a research project with the Catalan choreographer Toméo Vergès, whom I discovered through his play Anatomia Publica, which offers a theatrical view of fragmented everyday gestures, repeated until they appear surreal.

It just so happens I saw that Liz Santoro was also collaborating on FIXIN… Yes, on this project, she’s giving choreographic advice about the performative dimension. I greatly admire the work she’s doing with Pierre Godard on perceptual biases.

Are you particularly interested in the question of efficiency? It is one of my areas of interest, yes. One of the things that fascinates me the most in live music is the anticipation of the gesture, people whose intentions are very clear: their gesture is very clear, the sound emission is very clear, it always impresses me. And no matter whether it is a performer of written music or someone who improvises. But I find that there is something ineffective about improvisation. Quite often, improvised music is a gathering of people who do not necessarily have the same languages, who do not even necessarily work on the same aesthetics, who do not use their instruments in the same way and who, sometimes, even have completely different relationships with time, and who play concerts together. So for forty-five minutes, it can be very boring, sometimes even bad, and then all of a sudden, there are five gem-like minutes that emerge. After having gone along with this dogma of the freedom of improvisation versus the constraint of writing; after listening to it and making it myself, I realized that what is interesting for everyone is these five minutes. How to delete the rest? By re-establishing constraints, and it is between ultra constraint and zero degree of constraint that these five minutes can happen. It is obviously a commonplace, but freedom can only be thought of through coercion. In the world of improvisation, which is historically highly politicized and located very far to the left (from American free jazz that can be roughly equated with the political demands of Black Americans, to European improvised music that appeared in the 1960s and 1970s), there is this idea of freedom without constraint that is consistent with a form of political anarchism. As an artist, I am steeped in these stories and I have to get rid of them because they condition my choices. For me, starting an action openly and stopping suddenly has a real value of effectiveness. The information I send is direct. Everything I’ve been working towards in recent years is exactly that: a sound emission, a very clear intention. Hence this relationship to computer science and rationality, which I mentioned. These questions came about from my improvisational practice and a certain annoyance regarding those other forty-five minutes.

And so for FIXIN, the music is written, there is no way that it can go wrong, that it will go on the blink? Right. But I’m going to give the illusion that there are things that mess up, at least in the performed version. I am working in parallel on ramifications of the project: an installation version and a sound-only version, without the lighting part. Both will include more flexible modules where randomness will have a more important place. To go back a little bit, the genesis of this project was made with other prototypes—the ones I used with Zimoun—, made by another artist, Florent Colautti. For this version, I used a sound bank that I had made myself and which allowed me to improvise with the motors. Via TouchOSC and my phone, I controlled them remotely and live, while playing my drums, but always in this on/off way.

Whereas here, this is not the case… Here, no, no, not at all. At the beginning of the project, the possibilities seemed endless to me. I had to understand all the technical constraints at the same time as I was clarifying the artistic outlines. Randomness was part of what seduced me as a musician but did not seem relevant to me when I was imagining the interaction between the lights, the motors and me. I think that with a certain way of writing, I can give the illusion that I am interacting directly with the motors and the lights. At least that’s the challenge I set myself. The limit commonly attributed to writing is the repetition of the same and the boredom that might result from that, as an interpreter. However, the solution is simple: changing the writing, making the device more flexible… Nothing scary, when all is said and done.

You talk about a “man-machine”, about an extension of your body by the motorized system: were you already, as a musician, in a prosthetic relationship with your instrument? Yes, for a long time, actually. The orchestral experience has sharpened my awareness of timbre alloys. Being a composer mainly means organizing in time these possibilities which today can be infinite with electronics. Since I was twenty years old—when I started working with composers from acousmatic movements—I have been fascinated by the possibilities offered by the expansion of my drum set. I experimented with that in two directions: one via microphones placed on my drum set which passed through effects pedals; the other clearly acoustic but in a kind of mimicry of electronics: for this, I had to invent gestures peculiar to certain found objects (often kitchen things) but also to small sex toy engines, very easy and fast to handle. The goal being to go beyond the limits and paradoxes of my instrument to become a man-orchestra, if not a man-machine.

2 IN LOVE WITH: Sylvain Darrifourcq : drums, composition ; Théo Ceccaldi : violin ; Valentin Ceccaldi : cello.

3 MILESDAVISQUINTET!: Sylvain Darrifourcq: percussion ; Xavier Camarasa: prepared piano ; Valentin Ceccaldi: cello.

4 Némo is a digital arts international biennale held in Paris and Île-de-France.

5 Zimoun & Sylvain Darrifourcq, Time at a Loss #3, Mechanical Rhythms and Repetition, Outbound Series, curator: Mélodie Melak, Kunsthaus KuLe, Berlin, 19.12.2018.

6 FIXIN: Sylvain Darrifourcq: percussion, composition, design ; Nicolas Canot: digital design ; Maxime Lance: object design ; Liz Santoro: choreographic advice. Co-production: Hector/Full Rhizome; Biennale Némo/Arcadi/le 104, Paris; le Théâtre de Vanves; le Cube, Issy-les-Moulineaux; Le Lieu multiple, Poitiers; La Muse en Circuit, Alfortville. With the support of: CNC/Dicréam; Fonds d’aide à l’innovation audiovisuelle; Adami; Spedidam.

/ / / / /

FIXIN, public rehearsal at Le Cube, Issy-les-Moulineaux (F), 21.11.2019

Premiere at the Théâtre de Vanves (F), as part of the Némo Biennale, 4.12.2019

Le Générateur, Gentilly (F), as part of the Sors de ce corps ! festival organized by the Némo Biennale, 25.01.2020

Espace multimédia Gantner, Bourogne (F), as part of the “Algotaylorism” exhibition, curated by Aude Launay, 19.04 – 11.07.2020. Postponed, dates TBA

Image on top: Sylvain Darrifourcq, FIXIN, 2019. Photo : Romain Al’l.

- From the issue: 91

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Paolo Cirio, Computer Grrrls, Franz Wanner, Jonas Lund, Heather Dewey-Hagborg,

Related articles

Céline Poulin

by Clémence Agnez

Calla Henkel & Max Pitegoff

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Dena Yago

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad