Dena Yago

From the aesthetics of networks to the aesthetics of the precariat

Technology has created a new aesthetics. By declaring as much, we can already see what we are talking about. Here we have the emergence, from the shadowless space of air-conditioned data-centres, of the ghosts that we thought were once and for all cryogenically frozen. We can see them coming, we already sense on the nape of our neck their lukewarm breath smelling of phthalates and mist makers: green plants, Macbooks, yoga mats, Nike sneakers, Axe shower gels, life-size photo stock prints from the post-Internet years! But before hollering about the zombies’ attack of post-Internet art photos from the 2010s, we must again specify the opening declaration. The aesthetics in question here do not concern this thoroughly conscious gesture of artists who, either ironically fascinated or joyfully anxious, decided to wipe out the present by pushing to the limit the workings and the outward signs. What is involved is not an approach, a movement, a post- something or an –ism, nor anything else that we might call a position in relation to a system of discourses and praxes, in relation to a history and to institutions—which is to say that it is not a matter of art. No, it is a matter of observing a subjectless process, an avowed fact whose contagion is so widespread that it authorizes this general statement: technology has created a new aesthetics.

Some people name it, in the sense whereby they identify it after the fact, and in this case, they then talk of “Airspace”. The term appeared notably in an article in The Verge1, designating the strange geography produced by a globalized harmonization of tastes. Because of the influence of applications such as Foursquare, AirBnb and WeWork, it is possible to travel without friction by moving between strictly similar spaces. The fact, as the article underscores, is that this homogenization does not come from the worldwide hold exercised by a chain with branches all over the world. This is not, or no longer, the age of McDonalds, Starbucks and H&M. No, this similarity is due to independent decisions made by tens of thousands of people, acting in tune with their tastes, standards and own personal criteria, independent and yet all alike. Declaring that technology has created a new aesthetics does not mean that aesthetics convey the idea of a certain future, fantasized, no matter how close it may be, that one would postulate as being more or less correlated with a visible technological development: shiny, chromed, fluid, all smooth and all in curves.

The aesthetics that we want to deal with here, and qualify, have nothing to do with the futuristic and naively optimistic fetishization of that decade that is now decisively behind us. No wet-moiré or iridescent effect, no corporatism erected like a mood-board, no technological gadgets displayed like so many prosthetic limbs. Here, in the present moment from which we are talking, technology is to be taken in the sense of platforms—those “digital infrastructureswhich permit two or more groups to interact2”, putting the extraction of data at the centre of their model—and in a more tangible way, of applications, whose monopoly ends up by replacing the usual cultural and political structures.

Rather than an aesthetics deliberately identifiable as new, different, or special, technology, and its very real hold which is no longer just an image, has thus, surprisingly, produced a nostalgic aesthetics, based on the repetition of a litany where we duly find rough timber, factory lamps, small decorations, and organic food. This has more than a little to do with the structure of platform capitalism, placing at the centre a host of people working hand-in-hand with other people, in the illusion of a horizontality, even when those possessing the logistics now have an influence on an ever more crushing monopoly. And yet everything is based on a subterfuge consisting in encouraging the dissemination of a resolutely DIY and made-to-measure aesthetics, craft and craftsmanlike in order to change the hold of the large impersonal groups—which are nasty and bad, as we all know. This aesthetics is being, in its turn, de-professionalized: this vintage variety, hand-made, typical and folksy, and above all with a phony, disconnected localism, which is to be found, similar if not identical, all over the world, in places frequented by the mobile and freelance creative class, which eats local food and has been won over by upcycling.

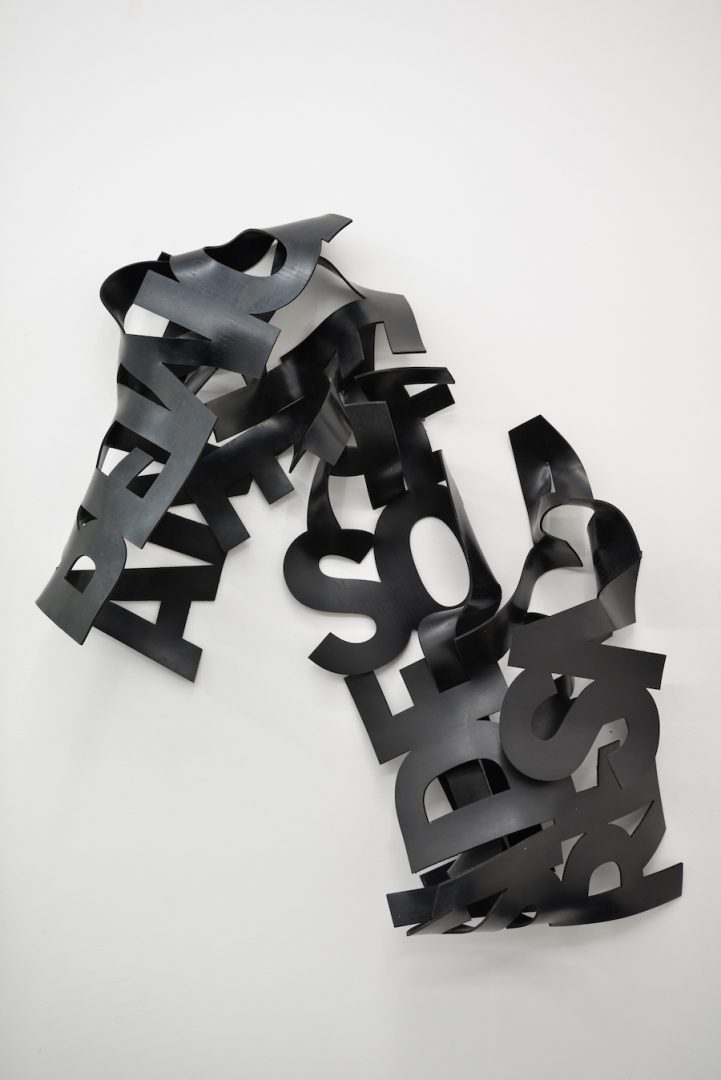

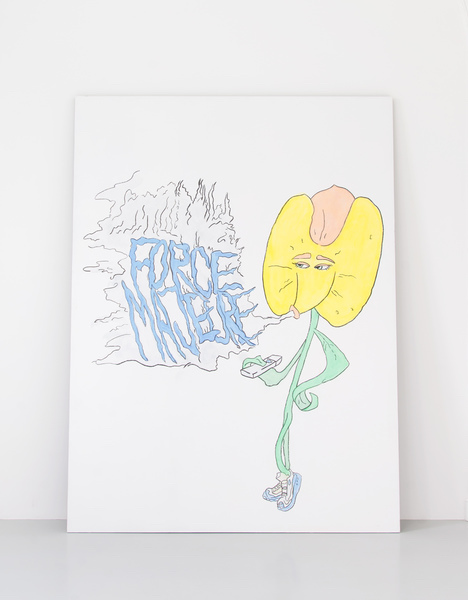

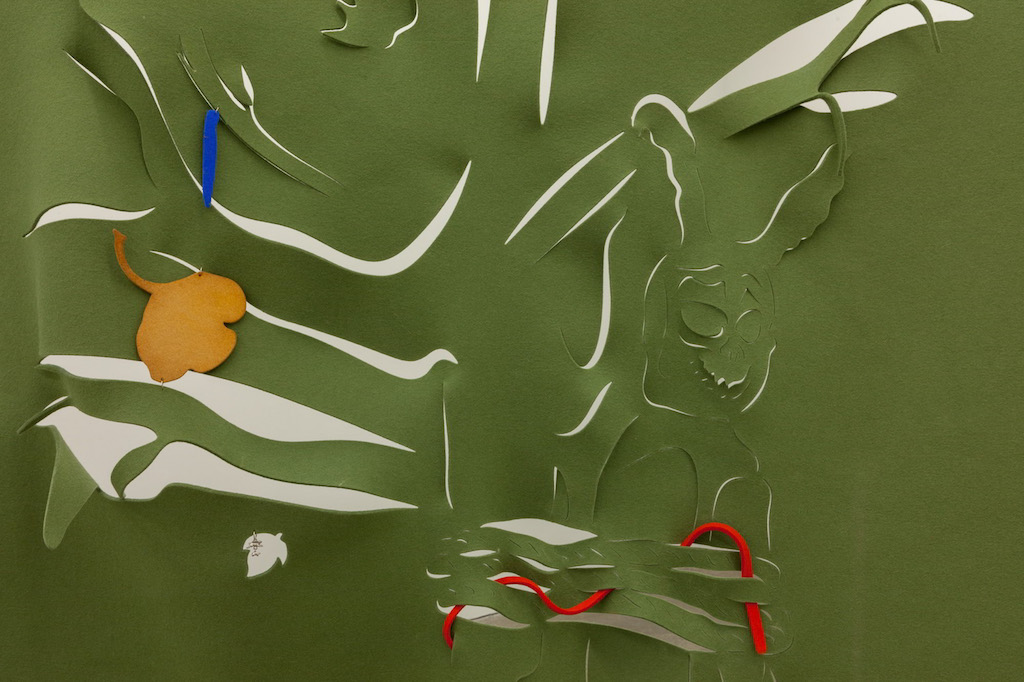

In Dena Yago’s exhibition “Force Majeure”, held last year at the High Art gallery in Paris, this “AirSpace” aesthetics appeared requalified in the form of a neo-pastoralism. Here and there in the gallery space were placed roses and lettering cut out in felt, whose painstakingly chiselled composition referred directly to the motifs of Quaker embroideries and, indirectly, to that predilection for the hand-made that we have just referred to. In the artist’s praxis, the cut-out felt has for some years now been imposed like a recurrent trope, with large panels hanging in space like draperies and curtains, or falling from the wall like so many skinned anatomical figures. Up until now what was usually involved was lettering, and more rarely cut-out figurative scenes. By choosing felt, one instinctively perceived, and in the wake of Joseph Beuys and Robert Morris, the presence of a quasi-body, a substitute of enveloping and comforting warmth. Added to the geometric motifs is also the reference to manual work and its precision, along with its contemplative and meditative values. The pastoralism in question, in the case of this American artist, might thus also, and more precisely, refer to the work ethic of Protestantism, also beneficial for the individual through the piece of work well made, in a way linking up with the celebrated ideals of care and #selfcare. This issue of “care”, a term which present-day branding is so fond of, was also incarnated through the other set of pieces in the show. On two large panels laid on the floor, a humanoid orchid was painted, with a mixture of acrylic, tempera, chalk and charcoal. Human-size or a little larger, this orchid appeared like a cartoon character, equipped with a pair of blasé or disappointed eyes, a mouth for smoking (or rather ‘vaping’, because who really still smokes these days?), leaf-arms for pushing over a pile of packages, and two feet wearing mood-of-the-day sneakers, meaning too big, in a Balenciaga-esque way. With Dena Yago, the cartoon flower, which is also a recurrent motif in her recent activity,3 assumes a quite specific significance. The fragile and demanding flower, set on desks in co-working areas and of companies at the cutting edge of progress, incarnates this sardonic irony: the flower embellishing the desk of workers survives as a result of meticulous and daily care, while these very workers are liable to be replaced at the first sign of weakness, and while the increasing privatization of all sectors is depriving most workers of any kind of social cover. The orchid which vapes staring into space, the orchid which, for better or for worse, contains a host of packages in its arms knows that it is obliged to put on a brave face, and hide the long shaking stalks: after all, it is part of the creative élite, it is free, it is flexible, it is mobile, and it is privileged.

If an aesthetics of work is what is involved, the fact is that the outward signs that we are referring to, the phony artisanal and what, in the case of this artist, is to be found under the reference to a shoddy, cheap pastoralism, correspond to a branding strategy, i.e. a subterfuge consisting in passing off a condition being put up with and suffered as a privilege chosen through the definition of codes that are sufficiently identifiable and desirable to establish and then consolidate, to the point of fossilization, the idea that liberty should in reality be called precarity. Since the turn of the 2000s, the notion of “artist capitalism”, as identified by Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello4 explaining how creativeness, inventiveness, task jobs and the absence of any distinction between professional life and private life, usually the lot of art workers, has trickled into this exceptional sector, and been imposed as a business model. But the observation remained blurred without an aesthetics and a style to incarnate it. Henceforth, like the expansion of the AirSpace aesthetics resulting from the instrumentalized concordance of a whole host of individual desires, another type of precarity is developing alongside the ordinary and eternal precarity of those who are left out: the precariat of the so-called creative élites.

The precariat is a tribalism endowed with a certain number of outward signs, and Dena Yago defines them better than anyone, especially when she focuses on office food, from photographs of her first solo show Esprit (2011)—scans of various ‘healthy’ snacks and other nibbles–to the recent Frieze article about the “Reddit cafeteria”, and the affective hold wielded over workers’ bodies by the offer of food at work; with regard to the work environment of the precariat, this latter is varied, healthy, eco-responsible and trendy. It has to be said that Dena Yago is well acquainted with these branding strategies. In 2010, aged 22, in New York, with Greg Fong, Sean Monahan, Emily Segal and Chris Sherron, she co-founded the K-HOLE consulting group, which, until 2015, would publish in PDF form trend-forecasting reports, usually marking art events and at times becoming, in the case, in particular, of the “normcore” concept, nothing less than viral phenomena. Today, she still has one foot in the world of the large companies based in Silicon Valley—having worked as a consultant with Tesla and Hulu, she then co-founded Are.na—, and the other in the art world; two ways of organizing work and two ideologies which are increasingly difficult to tell apart and often seem to merge.

The two forms of expression, the worked felt and the pastel tones, which are part and parcel of the aesthetics of the precariat, give onto a uterine space where the impression of a cyclical and repetitive time-frame masks the likelihood of the sudden break brought on by project-based work. Everyone is reassured, lulled, and put to sleep,6 so much so that this ever-growing and as if self-managed mass of the precariat has a possibility of social class in name only: because everyone feels pampered and privileged, certain of acting as a creative individual rewarded for his or her merits by their access to an AirSpace lifestyle, nobody will ever have the idea of joining together with their peers, and daring to look head-on at the collapse of the safeguards against the limitless extension of neo-liberalism, erected as a principle of government. Before grappling directly with the codes of the precariat, Dena Yago presented a certain emotional confusion of our reflexes scrambled by dint of being forced, from early childhood on, to experience empathy for cartoons thought up by large entertainment companies, before perpetuating the same adult reflexes, experiencing feelings of attachment for products and brands. At “In Escrow”, her previous show at the gallery in 2016, she presented a just as pastel, sickly, disconcerting and cartoon version of Alice in Wonderland, which was subsequently to be found in her exhibition “The Shortest Shadow” at Atlanta Contemporary, in 2018. Prior to this, the artist had produced a certain number of series about pets in large cities, sorts of somewhat limpid equivalents of precariat workers, when we regard them in the light of later works. Mollycoddled and at the same kept on a leash, with the one conditioning the other, care was already always flirting, in her work, with constraint, whether what was involved was photographs of dogs on leashes or muzzled in the exhibition “You and You’re People” at Boatos Fine Arts in Sao Paolo in 2014, with their frames set with precious talismanic, gris-gris letters, or, more recently, the companion animals in Fade the Lure,5 a compilation of poems and photographs in which we sense the smithereening of human relations and any sense of community, a lack temporarily palliated by means of canine substitutes rather then a turning against the oppressive system which is the cause of all that.

As an artist and poet, theoretician and startupper, Dena Yago starts from her personal experience of the world of work, a certain world of work, that form of voluntary bondage that lends the precariat its reality. In a way, everything in her work refers to branding, whether she more explicitly displays its workings by juxtaposing words and imagery (the lettering in space, the works of poetry) or whether she restricts herself to show its effectiveness in action (the felt, the cartoons, the food codes). More than any other organization of work, the advanced stage of neo-liberalism needs aesthetics to encourage membership in her project, so that everyone not only submits to it and tolerates it, but also applauds it with both hands, extends its hold, enjoys being in it and, above all, feels chosen and distinctive by having become part of an élite with such clearly identifiable and perpetuatable codes, thus justifying all sacrifices and, in the first instance, the submission of the body: for want of being free as air, one is at least welcomed into the “AirSpace”. Starting from her own experience, which is to say from affects as they have been felt, at once ambiguous and complex, Dena Yago’s works have, in their turn, a suggestive material quality, the evanescent seduction of the sketch, because celebrating or denouncing would be to reproduce the workings of the advanced stage of neo-liberalism, which is hijacking art and aesthetics, to set up its own systems of logic.

1 Kyle Chayka, “Welcome to Airspace. How Silicon Valley helps spread the same sterile aesthetic across the world”, The Verge, 3 August 2016.https://www.theverge.com/2016/8/3/12325104/airbnb-aesthetic-global-minimalism-startup-gentrification

2 Nick Srnicek, Platform Capitalism, London, Polity Press, 2017.

3 See in particular the lecture at the Pogo Bar in Berlin: “Dena Yago. On Orchids & Precarity”, 29 June 2019, and the article “What Affective Labour Has to Do with Reddit’s Corporate Cafeteria”, Frieze n°205, September 2019.

4 Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello, Le nouvel esprit du capitalisme, Tel Gallimard, 2001.

5 Ketamine, a tranquillizer for horses which has become a favourite drug of choice in the 2020s; Dena Yago, “On Ketamine and Added Value”, e-flux Journal #82,May 2017.

6 In late 2019 she published Fade the Lure, Paris, After 8 Books.

7 In the sense whereby Hal Foster, in his essay collection Bad New Days (New York, Verso Books, 2015) talks of “mimetic exacerbation”.

Image on top: Dena Yago, The Encounter, 2018. Charcoal and chalk on wall, variable dimensions. Courtesy the artist and High Art, Paris

- From the issue: 93

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Simon Fujiwara, Michael Rakowitz, Paul Maheke,

Related articles

Shio Kusaka

by Sarah Matia Pasqualetti

Julian Charrière: Cultural Spaces

by Gabriela Anco

Céleste Richard Zimmermann

by Philippe Szechter