Rebellion Against Extinction

This talk was first given on 31 January 2020 during the 2020 Verbier Art Summit and was first published in Resource Hungry: Our Cultured Landscape and its Ecological Impact by Koenig Books London. The Verbier Art Summit is a non-profit art platform generating new ideas and driving social change through art.

I’m going to talk about my recent work with the Sharjah Architecture Triennial, which will close very soon. It is the first major international platform on architecture to look at the architecture of the Global South, and, as curator of the first edition, I proposed the theme Rights of Future Generations. I chose this in order to foreground the intergenerational relationship in terms of struggles for environmental and spatial justice in the Global South, and part of doing that meant a kind of decolonisation of what we mean by architecture in the first place.

It is important to say that the Global South is not a region. It’s an archipelago, an archipelago that has survived empires, colonialism, capitalist extraction. Each island in that archipelago embodies a struggle to sustain alternative ways of being in the world, a rebellion against extinction that we could say has been going on for centuries.

The Sharjah Architecture Triennial gathers works by architects, artists, activists, choreographers, anthropologists, scientists, and performers to try to tell the stories of these struggles. Each project explores a unique relationship between generations, raising questions about the climate crisis and architecture’s broader environmental role.

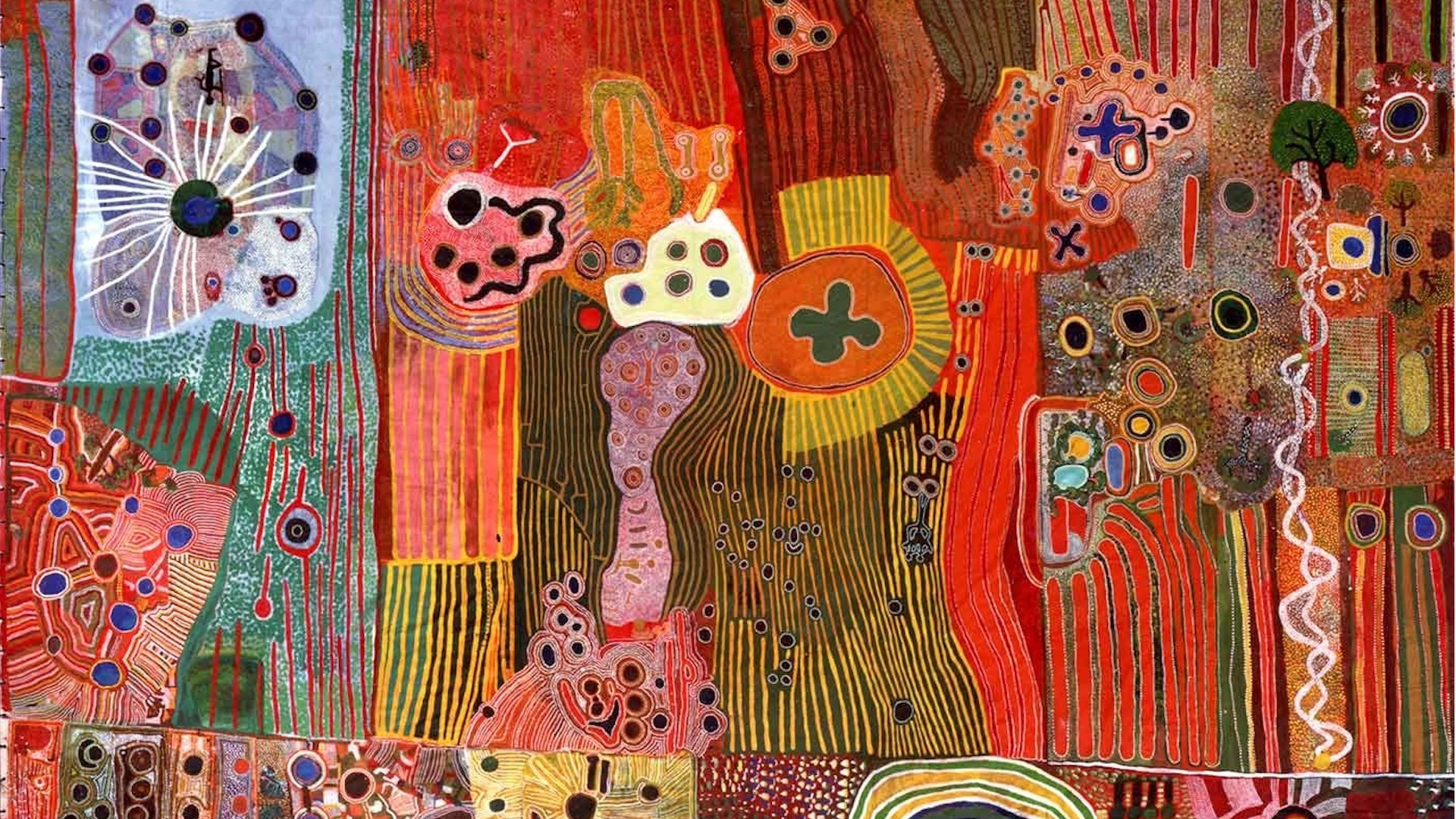

One of the most emblematic projects in the Triennial is an eight by ten metre painting produced by forty artists in four indigenous communities. The painting has lived in a large box in the storeroom of the Mangkaja Arts Resource Agency in Fitzroy Crossing for almost twenty-three years. How the painting came into existence is a rather astonishing story. In order to tell it, we have to turn to another kind of island, not one in an archipelago, but rather a continent with its own settler colonial history and an untold narrative which is as vast as its landmass.

The legal case of Mabo versus Queensland was settled on 3 June 1992 in Australia and, for the very first time, it recognised native title. It’s often been described as a landmark decision but it merely admits in legal form, what, to everyone, was already an undisputable fact: that Australia was inhabited before it was colonised and that, therefore, these inhabitants have claim to the land.

Mabo, named after the land-rights campaigner, Eddie Mabo, is often credited for overturning terra nullius, which is a Latin phrase, a legal concept, that translates as ‘nobody’s land’. Most of us Australians were taught that it formed a legal pretext for British settlement of the Australian continent, but we were all taught wrong.

Terra nullius begins to frame the account of white settlement in Australia about a hundred years after the arrival of the first fleet, so what Mabo overturns then is not only a moral fiction and a legal fiction, but a historical one. The continent was not settled; it was conquered—and the conquerors knew it.

Like so many of the lies that linger around our history, terra nullius is a fig leaf cast back in time, eventually taken for a historical truth. One of the most pernicious lies is that indigenous Australians lived in a state of subsistence. According to this image of pre-colonial, indigenous society, life was little more than a harsh, unending struggle to satisfy primordial needs with very, very meagre opportunities. And it’s a more pernicious lie because it is one thing to admit to conquering, but it’s another thing to admit that the conquered are your equals. Pre-colonial Australians did not live in a state of subsistence, and the ample time they allocated to their religious ceremonies is a ready proof of this.

The Brewarrina fish traps—an extremely complex set of weirs and dams—were indeed, a design project, an engineering project, an architectural project. What does the dam do? It collects fish in an enclosed pool so that indigenous Australians were never hungry. They could just go into the pool, pick up the fish, and eat them. We’re discovering thousands of examples of these kinds of structures in Australia. In fact, there is a revolution taking place in Australia in terms of the way that we understand our own continent—and part of that is the work of incredible books like The Biggest Estate on Earth by Bill Gammage (2017) and Dark Emu by Bruce Pascoe (2007).

As I learned art history in Australia in high school, the classic understanding of Australian landscape painting is this: European painters arrived with the First Fleet and, because their eyes are developed in the European context, they can’t see the Australian landscape as it is. They paint it as if it’s a European garden. Then we were taught of a revolution in Australian landscape painting in the nineteenfifties and sixties, as painters finally learn to see the Australian landscape with Australian eyes. In a sense they decolonised their perspective.

Bill Gammage does something incredibly interesting. He spent fifteen years writing his book, by taking these paintings, standing on the site where they were painted, and comparing the painting to the landscape. He read a series of settler diaries to learn what the diarists said about the landscape, and he makes the claim that the reason the Australian continent was painted by European painters as if it was an estate—a garden—was because it was.

So, what does that mean? The thesis in the book is that the entire Australian continent is made up of a series of mosaics. One of the mosaics is this small growth of bush, and then alongside that mosaic, is a patch of open grass, with a very clear definition between one and the other. Indigenous Australians would continually set very, very small fires to the landscape. Actually, the Australian landscape evolves in relationship to fire over tens of thousands of years. As the new grasses came through after the burn-off, kangaroos, wallabies and other marsupials would start to move through the landscape. Indigenous Australians would hide in the bush, and they would hunt the marsupials as they moved. What they were doing was coordinating the migration of marsupials through the design of the landscape, through the strategic burning-off of these patches in this mosaic that covered the entire Australian continent. That’s already extraordinary. But there’s another dimension to the story which is even more incredible. In each one of the language groups that I met, one of the members of the community would be allocated a totem. The totem might be an animal, or it might be a plant. That person was responsible for the entire ecosystem that that plant or that animal depended on for their survival. It was their responsibility—their legal responsibility and obligation, to look after it, no matter what. What that meant was, if someone whose totem was an emu, or a kangaroo, went from one community to another community, they would be introduced to the person in that community who was also responsible for looking after that animal. So, although they had different language groups, there was a transversal line that allowed them to connect ecological management of the land across the entire continent. Gammage’s claim is that the only way to understand the Australian continent prior to settlement, is as a single estate.

So, the continent was designed—but what kind of a design was it? It was a design that we couldn’t recognise when white settlers arrived. Its ecologies were modified, its rivers were controlled, its fields were cultivated, its movements and cycles and rhythms were manipulated and harnessed in a grand choreography spanning thousands of years. How’s that for an image of Australia? A vast intergenerational design project at the scale of an entire continent.

Despite the evidence, as I said, white Australians couldn’t recognise it. They still can’t—but it’s changing. Eventually, though, it too will become an indisputable fact.

Let’s take a recent piece of research on the veracity of oral testimony in Australia. Researchers conducted an experiment where they interviewed twenty-three different Aboriginal communities around the coast of Australia, asking them whether they had stories about the historical sea level within their oral tradition—stories about where the shoreline used to be. And they found that twenty-one out of the twenty-three communities they interviewed, accurately corroborated the exact position of the shoreline.

Now, that might seem unremarkable, except that the sea levels that were being described, were between 7,000 and 18,000 years old. Think about that: that’s an empirically verifiable story, transmitted across three hundred to seven hundred generations. Think about the kind of social structure it requires to accurately transmit stories that far in time. It’s before the invention of writing; before the invention of language. Despite the time that’s passed, despite every attempt to silence the messages that they carry, despite everything that’s happened on that island continent since 1788, those signals are still with us, and they can be made out if we’re prepared to listen. If we’re not prepared to listen, then this is the consequence [showing video of recent bush fires].

Right now, in Australia, there is a very politicised argument taking place where only one side is saying we have to learn from indigenous land management systems. Indigenous land management is not separate from the environment, and the Australian environment has evolved around fire. Fire is a natural part of the Australian environment, and, interestingly, the prime minister of the conservative government that we have at the moment—who did he choose to attack? He chose to attack the authors of those two books that I just discussed. That shows how dangerous those ideas are. Imagine, the prime minister attacking a scholar writing a book about land management? Just look at Mount Kosciuszko after the fires, it’s a complete apocalypse.

In 1993, in the aftermath of the Mabo decision, the Native Title Tribunal was established in Australia. As you will all know, in Australia the state is the sole source of law. That law, when it comes to property, consists of public, verifiable statements such as maps, surveys, titles, and deeds. But there is another legal order in Australia in which the state is not the only source of law—however that legal order transmits its law orally. It’s not written; it doesn’t have maps; it doesn’t have surveys; it doesn’t have title deeds; it values secrecy and initiation rather than public statements.

With the Native Title Act[i], two radically different legal, moral, and ecological orders came into contact. Their encounter raises difficult questions about the past, present, and future of relationships between black and white Australians.

So, let’s explore how it works to make a native title claim. In 1993, a group of communities from the Great Sandy Desert met at Lampu Well, which is on the northern end of the Canning Stock Route. The Land Council chairman at the time explained that, under the Native Title Act, the claimants would have to prove three things: their culture and their law; where they came from and who they were; and where they walked on the land.

Over the next four years, community members, working with anthropologists and the manager of the Mangkaja Arts Resource Agency, returned to the country to try defining the area of the native title claim. The claim area that they would eventually seek to ‘win back’ was 83,886 square kilometres, which is about twice the size of the Netherlands. But during this process, the question remained over how to establish, in front of an Australian legal tribunal, their culture, their law, where they came from, and who they were. In other words, what, in the eyes of the Australian legal system, would constitute proof of the fact that they have had land tenure going back tens of thousands of years?

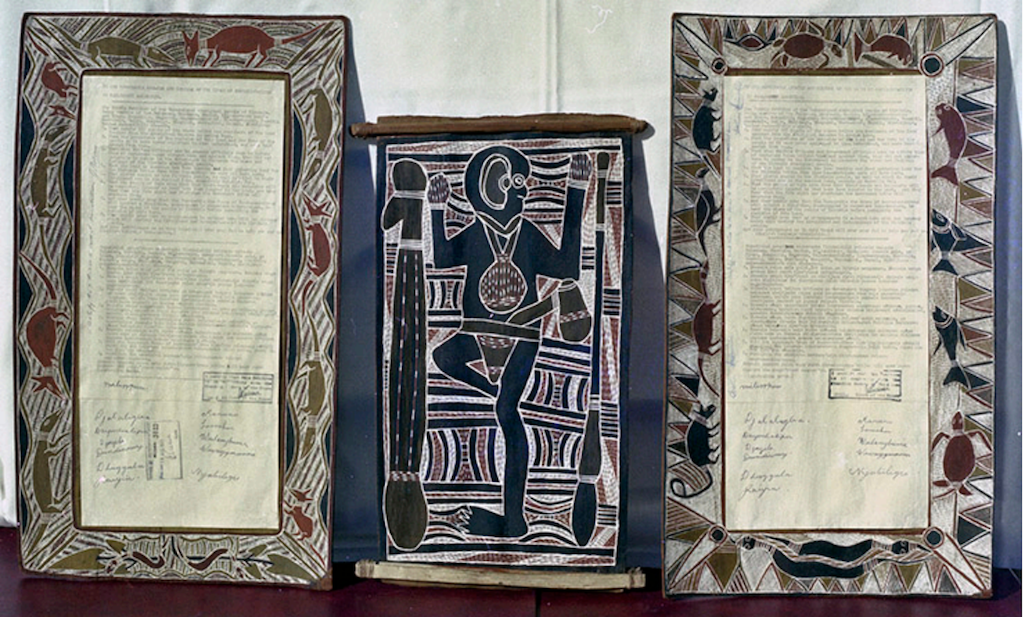

Then they made the most startling decision: they decided to make a painting to prove their title claim. It would be the first and, so far, the only time in Australian history, that a painting would be entered as evidence of native title.

The artists had to decide what kinds of stories to share with each other, because the different communities each have their own stories, and—under normal circumstances, they’re legally obliged to not share those stories with other people. They also had to decide what to share with the Australian legal system because, of course, there’s huge amounts of distrust.

They decided to break their own laws, and to share the stories with each other, and to share them with the Australian public and the Australian legal system in order to win their land back, which makes this project—the painting they eventually make—completely contemporary, it’s not a traditional painting. Then they made another really incredible decision: they decided that, despite their linguistic differences and their cultural differences, they would paint waterholes. It’s something they call ‘jila’ because it was water that made all of their stories commensurate. Obviously, water is an incredibly valuable thing in the desert.

On 9 May 1997, after four years of meetings, a group of more than forty Aboriginal men and women from the Walmajarri, Wangkatjungka, Mangala and Juwaliny communities get together at the Pirnini outstation, which is about a six-hour drive south of Fitzroy Crossing in the Great Sandy Desert. The plenary session with the National Native Title Tribunal was just about ten days away.

The following day, on 10 May, Jimmy Pike, one of the artists, takes a brush and makes the first mark, drawing a line of the Canning Stock Route. That’s the first line made on the eight by ten metre canvas—from one end of the canvas to the other. His fellow artists ‘find’ their country; they sit down; and they begin painting.

After ten days of painting, the forty artists that had gathered in Pirnini to paint proof of intergenerational land tenure for the Australian Native Title Tribunal, finished their work. The painting is called Ngurrara II. ‘Ngurrara’ means the feeling you have when you’re at home. Ngurrara Canvas II is so much more than a painting. It’s a strategic intervention in a land-rights claim; one that adopts, and adapts, traditional laws and stories about ‘country’ to produce legal and political effects by using aesthetic means. That makes it completely singular in an already rich tradition of indigenous painting.

On one hand, it’s a map in a cartographic sense because it can be said to point to things, and indeed, that’s also how they use it. In a very literal and material sense, it is their country. When they stand on it, they say that they’re standing on country. It’s how the law is expressed. It also talks about the way ‘rights to tell stories’ are differentiated amongst different members of the community. It’s a site for ceremonies of cleaning, of maintaining, of awakening. It’s the embodiment of kin and the home of ancestors—those things are in the painting for them. It’s a carpet. You can stand on it, and you can dance on it. They let their dogs walk on it. There’s a terrific story of the head of a very well-known institution in Australia coming to see the painting and being absolutely furious when he sees them walking on it. He says, “You have to decide what it is!” What’s so beautiful is that they don’t have to decide what it is. In fact, it’s undecidable. It’s a unique multi-level object, the likes of which I’ve never come across in my life, and that non-indigenous people will only ever apprehend at the very edges of its meaning.

With the painting completed, the artists insist that the hearing takes place on land. In a kind of Werner Herzog, Fitzcarraldo-esque moment, the Australian legal system decamps to a remote site in the Australian desert to hear Kogolo versus the State Government of Western Australia.

As they’re called to testify, the various artists walk over to the part of the painting that represents their country. They stand on it and speaking either in English or in one of the four indigenous languages, they tell the story of their life. They tell the story of who they were, of how they moved through the country. They expressed their culture, their law, where they came from.

One of the tribunal members says (in the evidence) that it was “the most eloquent and overwhelming piece of evidence that had been presented before an Australian legal system”.

The verdict took place ten years later, in 2007. Were they successful? Of course they were.

In the course of delivering his judgement, Justice Gilmour said, “Can I say that in making these orders this Court does not give you native title? Rather the Court determines that native title already exists. It determines that this is your land. That it is based upon your traditional laws and customs and it has always been. The law says to all the people in Australia that this is your land and that it has always been your land.” And we should add that it will always be their land into the future, an area of more than 80,000 square kilometres returned to its traditional owners using an eight by ten metre painting, that’s not bad…

I actually first learned about the painting in a legal text Declaration of Interdependence: A Legal Pluralist Approach to Indigenous People2 (2014) by an anthropologist called Kirsten Anker and I thought, “There’s no way this story can be true! How come I’ve never heard of it?” Of course, it turns out that nobody, or very few people, have heard of the existence of this painting. We’d been working on the project for months—but from London, from the perspective of the Institute of Contemporary Arts (the ICA). I was thrilled when, after months of discussion, the ICA agreed to meet with me.

In April 2019, I travelled to Western Australia to meet the surviving artists and nominated descendants of the deceased artists. In fact, there’s only six surviving artists out of the original group of forty. At the Karrayili Education Centre in Fitzroy Crossing, I came to explain my ambitions for the Sharjah Architecture Triennial, and to hear from them their ambitions for the canvas.

Terry Murray was the youngest of the painters on the canvas. He opened up the session with a minute’s silence for all the people that had deceased, for all the previous generations who’d been part of the canvas, but who could not be there. From the very start, the whole idea of intergenerational rights could not have been expressed more powerfully.

As you may have noticed, the painting is called Ngurrara II, as the artists made a second painting. They kind of mucked up Ngurrara I—by their own admission, they just didn’t get it right, but because it’s a first edition, it gets acquired by the National Gallery of Australia. So, the really important painting, Ngurrara II, is one of the only collective works to remain in community ownership in Australia. Their dream is to exhibit the canvas on the site where it was painted, in a remote part of the Australian desert, and to try and develop an economy around it, which is the project we’re just about to start working on.

And as to my ambition—to bring this painting to Sharjah, I didn’t need to explain the project to them. They just got it. The only question they asked me was “Do the people who made the other works in the exhibition care about their country?” I could answer positively and the canvas arrived at the Sharjah Architecture Triennial and was installed in one of the Sharjah Art Foundation spaces. During the opening programme, on the third day, there was an awakening ceremony, when completely spontaneously, it was repeated what had taken place during the hearing, except, this time, it was in a sense very emotionally charged because it wasn’t the artists themselves sharing this. It was the artists’ sons, or the artists’ daughters, walking over to the spot on the country that parents had painted and explaining to us what each part of the painting meant to them.

I’d like to conclude by just talking about one very small aspect of the painting: that blue circle with the white lines extending out from it, is the jila, the waterhole. The jila has almost the same size in the painting as it has in the actual 83,886 square kilometre area, but the tiny little jila is being understood as so precious, and the relationship to water that comes along with that is so sacred, that this is how they read the environment. What is absolutely extraordinary to my mind is that the scale of the jila in the painting has got nothing to do with its dimension in real life because, in fact, they’re commensurate. More than that, the white lines represent the pathways that people take, entering a vast salt pan from every single direction, to come to the jila. The paths themselves (you’ll have to imagine a completely flat white surface) are a couple of millimetres deep. They’re almost invisible—just very slight depressions. Each community follows that path because they know that was the path their ancestors walked on to get to the jila.

What’s really beautiful here, is that it is rendered with a kind of clarity of a site that is so sacred that it forms the focus of an entire conceptual, legal, religious, and ritual system in one of the hottest and driest environments on the planet, and it has done so for tens of thousands of years.

What signal does that transmit to us today? These small facts point us towards something which I think is very fundamental. In this painting, what we find is not just an archipelago of jilas, but the materialisation of an alternative mode of existence; an alternative set of understandings, of perceptions, of feelings between people, and between those people and their country.

The Sharjah Architecture Triennial brought together various sites of social struggle to try to explain how precious these alternative modes of existence are—especially the way that they embody different ways of being in the world, outside of the xenophobic, extractive, capitalist modes of relationship that currently dominate the world, that lead us to exhaustion, and soon to extinction.

The struggle of the Ngurrara people is one of countless struggles that occur across the Global South. We are living in the twilight between worlds. The planet that we think we’re living on, no longer exists.

Global temperature rises will soon make the centre of Australia unviable for human life. Soon, a second set of irreversible processes will lead indigenous Australians to leave their country—maybe for ever.

Today, all of the walls in the world, all the refugee detention centres, all of the processing facilities, all of the exterminations and decimations of indigenous cultures, all of the Trumps, all of the Bolsonaros, all of the Morrisons, cannot insulate the Global North from experiencing what it means to extinguish a world.

[i] The Native Title Act 1993 is a law passed by the Australian Parliament, the purpose of which is “to provide a national system for the recognition and protection of native title and for its co-existence with the national land management system.”

2 Kirsten Anker, Declaration of Interdependence: A Legal Pluralist Approach to Indigenous People (2014), Routledge 2017.

Image on top: Ngurrara: The Great Sandy Desert Canvas

Related articles

An exploration of Cnap’s recent acquisitions

by Vanessa Morisset

Curator’s marathon : Frac Sud, Mucem, Mac Marseille

by Patrice Joly

Exhibition-Making as Practice (A Journey)

by Agnès Violeau