Thomas Teurlai

Subsidences

21.01 – 15.05.2022

Frac Bretagne, Rennes

To Attack the Attack or the Underground Resurgences

In the beginning, there will be chaos. In the work of Thomas Teurlai, if something alive should materialise from what remains, it will be through a strategy of subversive pleasure.[1] In other words, for a relative subversion of power to occur, a sense of urgency will be required. Beginning with his studies at the Villa Arson and through the co-creation of Wonder—a Paris-region artist collective—the artist has continually sought out autonomous zones in which to forge spaces of resistance. A vast, shadowy zone exists between what is alive and what is dying, one that is filled with fluctuating energies, and no detail is too small for the artist. Entwined in clandestine spots, some works give only a few clues for their decoding; they oscillate between spaces of liberty and spaces of action, from defunct industrial parks and other abandoned spaces to the institution. His practice is neither definitively rooted nor entirely nomadic. Often infused with a collective energy, it has built itself upon contact with other artists and multiple collaborations, with equal focus on cooperation and transmission.

Through “Subsidences,” at Frac Bretagne as well as with future exhibitions: at CAPC Bordeaux and Jean Tinguely’s Cyclop in Milly-la-Fôret, Thomas Teurlai’s efforts reveal sites which are dedicated to the conservation or exhibition of art. Like temporal machines, these projects weave together a multitude of stratified narratives. Circuits are formed between them, allowing psycho-kinetic experiments to take place, giving way to mechanical epilepsies—bright and often heady—whose machine magnetism, equally joyous and sobering, aligns itself with waves and frequencies, driving energies and natural rhythms.

Sculpture, or the infernal cycle of the fossil of Capital[2]

Some artists have a way of creating works with an impressive life-force, playing upon the silence of bodies and low light of the spaces they exhibit in. Thomas Teurlai is one of those artists. He captures the essence; even the very energy of the sculptural medium and its inherent potentiality. He does this by making audible an electrical current or by rendering the smell of cooking oil which alters the lights in a fishing warehouse in Iceland; by experimenting with a tent which has been soaked in clay and then baked in an oven in Dakar, in Senegal—a mixture of camping, ancestral practices, travel adventure and DIY. In another example, a car motor runs in order to create a sculpture: trainers and baseball caps made of clay dry near a fire in a warehouse in Baltimore; a shower stall explores the dielectric properties of water, also a blustering factory produces mouldings of the inside of old refrigerators, resulting in sarcophagi-bleachers.

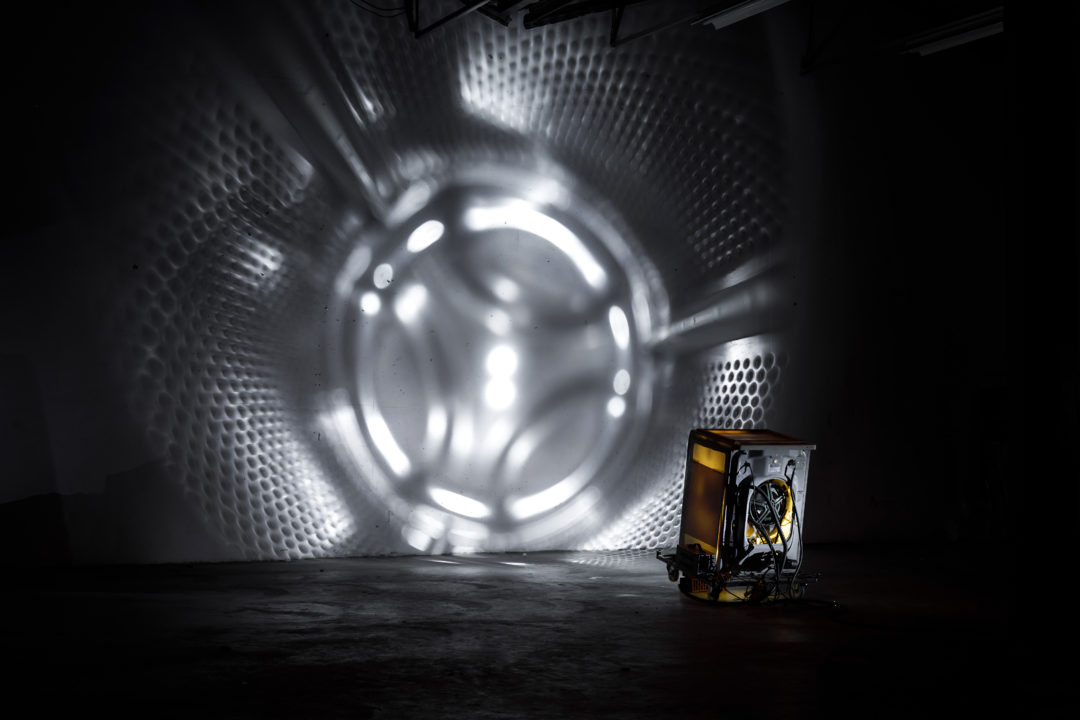

All of these works hold influence over the construction of the spaces that receive them. The poetry that emerges is a result of a near-performative distillation of experience. In order to set off forceful feelings and a vibrating motor force, Thomas Teurlai sculpts the contours of a potential future by exhuming everyday objects. In doing so, he unveils their salient skeletons and the fissures of a meticulous engineering. In Washing Skope, a washing machine has become a 21st century magic lantern which becomes active during the wash cycle, making its inner workings visible. The installation is also filled with microphones, making its insides audible. Far from empty, the machine—an object which has undergone the attribution of certain signs of life—crosses the line from utilitarian to marvellous, from banal to particular. Possessing a spellbinding visual and aural power, the installation unlocks our archaic relationship to objects, creating a path toward emancipatory thought; underground and spiritual, heady and magical. Through this modified machine, the artist riffs on involuntary acts, the mechanic unconscious and repetitious cycles of Fordism—from neurosis to dependency and machination, which exhaust and dehumanise.

In a world divided by capital and work, in order to find release from the servitude of maximum productivity and blind devotion to economic growth, thorny issues will need to be addressed. Beginning with the steam engine, the human being, having been made into a tool, has become just another link in the chain. The theoretician and militant Marxist feminist Silvia Federici maintains that, in her view, the first machine “developed by capitalism” was “the human body, and not the steam engine or even the clock”.[3] Having become a part of the work force, this would then represent the death of the magic body. If one of the effects of Taylorism on the body—and its desires—was its automatisation, Thomas Teurlai takes it even further: not into the realm of the absurd but towards a clairvoyance that upends the notion of the man-machine in order to extract this “peasant, pre-industrial, magic body” all-important in the work of Federici.

L’âge du faire [4] : Hacking Towards Autonomy

By mimicking different production methods, Thomas Teurlai electrifies schools of thought and mechanical movements from the 19th and 20th centuries in an alchemical mixture that he whips up, stirring the viewer. He does this by drawing upon the infinite network of freely exchanged resources which can be found on the Internet, choosing amongst the innumerable tutorials accessible to everyone online. What is at stake here are the redistribution of resources and the dissolution of hierarchies through the use of technologies which avoid exploitation.

Transchrones, a complex and composite installation which is somewhere between sculpture, video projection and machinery, takes the viewer on a wandering tour around an inhospitable Earth. Life has become unsustainable here due to subsidence, a sudden geological collapse—although sometimes this phenomenon can happen gradually—of the earth’s core, under the weight of something which has been added to the surface, for instance with the excessive use of concrete. A kind of sculptural thinking machine, the work balances on the edge of fiction and its power through the use of the performative, restless and poetic voice of the writer Alain Damasio. His voice takes over and fights to build up the malleable and rotary power of words. His shaky, shamanic breath literally sculpts the language and the space around it while the sculpture; both motor and magic lantern, spins the imagination of the viewer. The Frac Bretagne building becomes the centre of gravity of the telluric work of Teurlai-Damasio, resonating equally with the gothic-occultist architecture of Odile Decq and the site-specific work by Aurélie Nemours adjacent to the Frac. These entropic visions are caught up in a phantasmagoric spiral; by turns fabulations, internal landscapes or memory-dreams, they create a link between the future and the digital archives of human memory which take on a patina over time.

(with Alain Damasio) © Thomas Teurlai. Photo : Salim Santa Lucia

Thomas Teurlai disassembles the ethnocentric hegemony of academic knowledge, built upon the dualisms of nature and culture which allowed the development of exclusionary practises inherent to the climate and economic crises. The artist takes on a project akin to that of Australian writer, theoretician and sociologist of new medias and communication McKenzie Wark: now is the time to take possession of and control information. With the political philosophy essay A Hacker Manifesto, published in 2004, as well as with the recent Capital is Dead, Wark defines the “hacker” class—which includes members of the purported “privileged” class due to their creative and technical skills—in opposition to the “vectorialist” class, who profit through domination, exploiting the technical universe which was dreamed up and created by the hackers. While computers may have enabled an increase in knowledge and skills—beginning a revolution which led to the creation of new spaces for individuals to re-invent themselves, the Californian counter-culture of the 1960s nonetheless upset the status quo by idealising a near-spiritual technological search to fluidify our lives. In this utopian and dystopian cauldron made in the American West, deregulation and inequalities continue to prosper and nourish an ambivalent fascination with the machine and our dependence on it. Beyond this technological mirror, a resistance is being pieced together. Action is direct, it cultivates its autonomy: that of voltage in (re)volt.

A Pattern of Aliveness

It is through the plucking of practices that jam the machine that Thomas Teurlai reveals the porosity between biological, political and economic knowledge. It nonetheless avoids falling into the trap of neo-evolutionary dualism, which would create an opposition between global technology and local traditions. While his work borrows storytelling styles from the landscape it passes through, it also reflects the toxic, destructive potential of technology. It highlights the role of mechanisation in social processes in order to sketch out and waylay the contours of an aesthetics of disaster, fed by apocalyptic discourse and the romanticisation of ruins. Thomas Teurlai can be considered as furthering the discussion begun by Achille Mbembe, who analyses the becoming-artificial of humanity and its counterpart—the becoming-human of machines. In Brutalism, the author stresses that “to bring life forward from that which is unlivable (…) the 21st century (is) the road toward a world of fabricated nature and fabricated beings (…). Technology therefore establishes itself as ontological destination for all living things”.[5]

© Thomas Teurlai. Photo: Salim Santa Lucia

The totemic work Bootlegg/Hydroponix; organized in France, Senegal and the United States, is a suspended garden and a closed-circuit laboratory with its own irrigation and lighting system, where existences are “composted”. With this work, Thomas Teurlai undertakes a botanical turn in sculpture: through the principles of hybridisation and mutation from the plant world, a given site is as important as giving life. A living and movable archive of the pharmacopeia of cities or medicinal plants becomes a sculptural and germinal flora. This reservoir of strength frees us from the trap set by machines in the spirit of a new organisation for living things but also sets us up for failure due to its speculative and productivist perspective.

Despite this warning against the standardisation of living things, the work of Thomas Teurlai has given near-surrealist poetic experience a chance to shine: bodies bound by labour or the economy make room for beings who find ecstatic experience by going beyond the self in order to bloom and resist.

[1] Hakim Bey, The Art of Chaos. A Strategy of Subversive Pleasure, Paris, Nautilus, 2000

[2] Title of the book by Andreas Malm in which the author reconsiders the connections between industrial capitalism, energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions in the context of what he refers to as “the fossil economy”.

y theservoirthe pluckingncee. non as “nections between industrial capitalism, energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions

y theservoirthe pluckingncee. non as “nections between industrial capitalism, energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions

[3] Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch. Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation, Paris, Entremonde, 2017, p. 258.

[4] Michel Lallement, L’âge du faire. Hacking, Work and Anarchy, Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 2015

[5] Achille Mbembe, Brutalisme, Paris, Éditions La Découverte, 2020, p.8

. . .

Image en une : Exhibition view Subsidences, Thomas Teurlai, Frac Bretagne, Rennes. Bootlegg/Hydroponics, 2021 © Thomas Teurlai. Photo: Salim Santa Lucia

Related articles

Mondes nouveaux

by Patrice Joly

Sculpture Garden

by Patrice Joly

Anita Molinero

by Elisabeth Wetterwald