Étienne Chambaud

Interview conducted by Marie Maertens

Étienne Chambaud opens Esther Schipper’s new gallery in Paris with a solo show, while his exhibition “Lâme” at the LaM opens on 13th October.

“Lâme” at the LaM is your first solo exhibition in an institution. Did you develop it, as you often do, in relation to the context and the place?

This is an exhibition that I have been working on for a year, in response to the curators’ wish to carry out, at least in part, a project that was akin to a retrospective. A work of reflection was based on existing works, starting with the film La Nuit sauve, on which I have been working for a long time and of which I am showing here a first, still unfinished version. It gave a framework to the exhibition, which is enriched by both recent and very old productions, since one room shows drawings and collages made when I was three or four years old. I also reflected on the meaning of collections, literally, by exhibiting a year’s worth of dust from the LaM and by taking 19th century paintings from the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Lille and specimens from the same period from the Musée d’Histoire Naturelle out of their storage rooms. I then combined these empty landscapes with these stuffed animals in a device that resembles a cage, a wall or a scaffold. It is both an exhibition within an exhibition and a transitory work whose components will return in a few months to their respective storerooms.

In all the areas that your work covers, there are always reflections on the redefinition of the work of art. Do you emphasise this here?

I am indeed interested in the somewhat contradictory relationship that we have with works of art, exhibitions and the experience in general. The title of the Lille exhibition is quite evocative of this contradiction: “Lâme” combines the French words for blade and soul, cut and continuity, distinction and infinity. I am interested in this ambivalence between what engages the senses, in particular with this multi-screen film, which is with music generated, odours, light pulsations, etc., while positioning myself in the genealogy of conceptual art, in other words, in a critical relationship to art, or let’s say cerebral art. But to do this, you must keep a distance and you can’t be completely struck by it.

Do you also take the liberty of going for something a little more spectacular?

I realised that it was interesting not to always just place simple objects that exclude a priori, but to work on this gripping form, on what is perhaps more of a performance or an experience, before focusing on reflection, or even working against it. To have to feel and think simultaneously is certainly the hallmark of art. To be gripped, to let oneself be gripped, but also to grip in turn is a rather idiosyncratic thing about the relationship to art, and this is what I try to produce in my work in general and particularly in this exhibition.

Even more so because it was an institution?

Not only, because it is also true for the work that I am presenting in my exhibition Expansion for the opening of the new Esther Schipper gallery in Paris. The work that takes up a large part of the space, Syrinx, is a sound piece that is rather discreet in its physical presence and from which not much can be deduced from its device alone. Based on an artificial intelligence that has learned to sing like birds of several species, the piece produces a constantly changing environment. Different songs are generated and appear here and there in the space. These birds can appear calm or anxious, stay for a few seconds or many minutes. They may meet, attract or frighten each other. When they meet in the exhibition space, they can learn from each other and will gradually change. A nightingale will borrow from the grammar of a mockingbird, while a duck will use the vocabulary of a crow. The time of the exhibition is thus a time of transformation, contagion and the production of new voices, even new species. The relationship to the experience of this work and to what one might have heard in it is very different from a reflection on the process of the piece itself. So here again, there is a difference between how the piece affects the senses and how it affects thought.

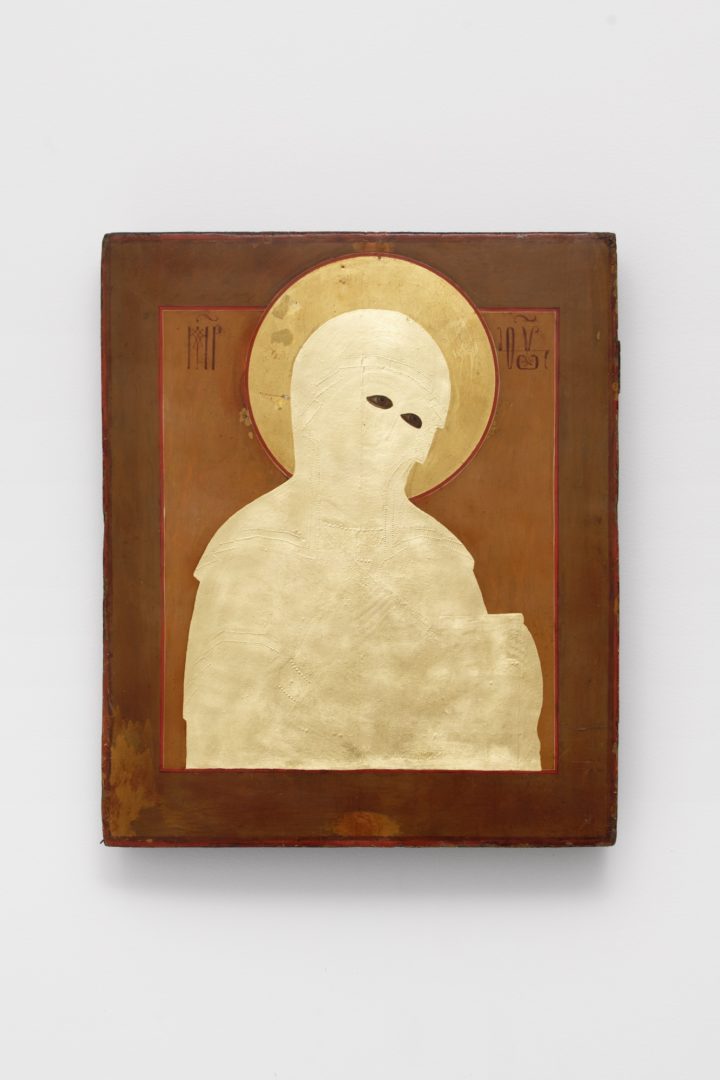

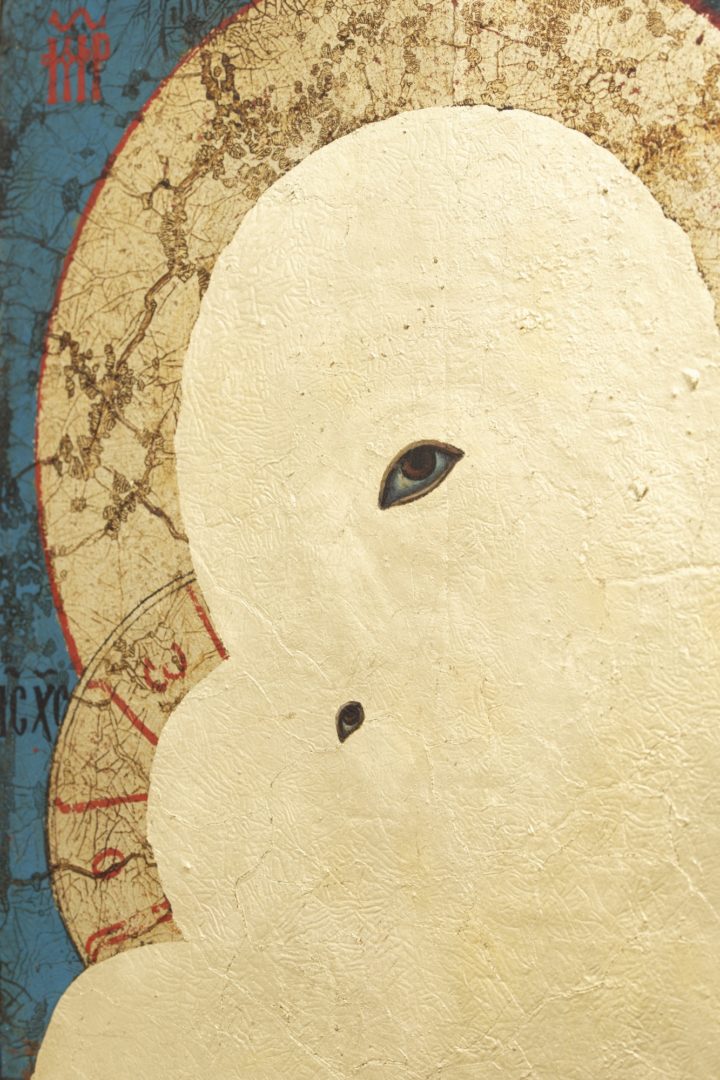

You are also presenting the sequel to the Uncreatures, which you unveiled at your first exhibition at Esther Schipper in Berlin in 2021…

While the Uncreatures are based on orthodox icons, this new series, the Stases, is constructed from oklads, embossed brass or silver pieces that were used to protect or decorate orthodox icons. Having lost their icon, they are left without function, like abandoned oklads, faceless masks…From these metal plates with holes in them, I wondered what could take the place of these absences. I wanted to make things grow through these forms of faces, hands, and feet…I then worked on a computer simulation of growth to generate forms constrained by these oklads. Various scales, types and patterns are created using the rules for the growth of certain crystals, plants, tree barks, fungi, or animal cells, tissues and organs, whether healthy, diseased or decaying. Like an excess born of an absence, the digital simulations are then discontinued and transformed back into objects that emerge as a fixed moment in the process, a suspended time, a stasis.

This again seems to show that, in addition to rigour, you allow yourself more formal freedom, to even let chance intervene. In the past, was this form of distance that you fostered with your works also with the viewers?

It’s true that, in my work, there is a difference between the time of the development of the works, which is a moment of great accumulation of thoughts, knowledge, research, resources, attempts, incidents… and then that of the exhibition, which is not at all a moment of communication of the work process. It is then a question of finding the most appropriate form of break…

A bit like pruning?

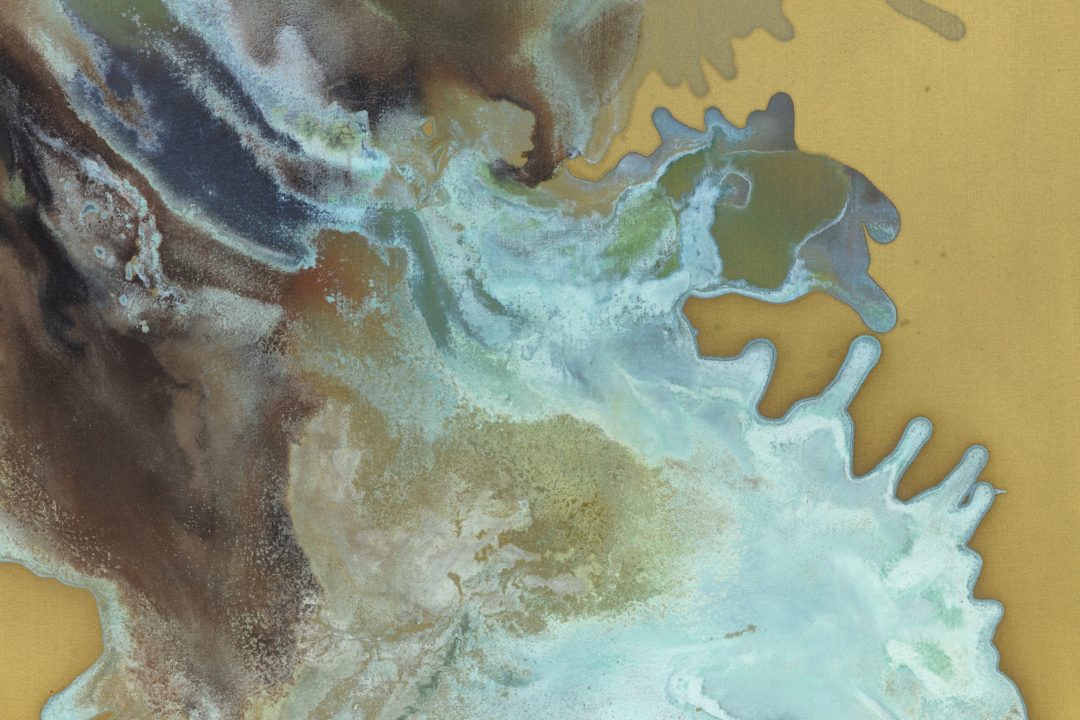

Yes, it is like pruning. The exhibition is for me a moment of break. My work process stops. The work becomes autonomous. It can be silent and orphaned, or it can generate endless nightingale calls. It no longer needs me. In some works, perhaps even in most of them, I set up a working device that will partly generate the work, with or against me. This can be by chance, a material process or logical constraints. For example, in the Nameless series – made of oxidised animal urine – I have no idea what the result of the works will be when I pour these liquids onto the canvases coated with copper pigments. There are surprises, failures… As with Syrinx, I don’t know exactly what will happen. The birds can be depressed, happy, come, not come and create all sorts of different sound environments that I have absolutely no control over.

There is also an element of randomness in La Nuit sauve, although it is based on control…

This film, about capture, focuses on the animal body and the devices that have framed its visibility during modernity. For years, and for months, I have been filming animals in cages in different zoos. I have also made long tracking shots in the reserve collections of the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris. Another sequence tirelessly follows a piece of string on the ground on a theatre stage, filmed by a robot whose lens/gaze seems to be trapped. Broadcast on three double-sided screens, the video installation is like a minimalistic version of a labyrinth. We are in front of or behind the image, without an overall perspective. Then something happens in the exhibition space. An algorithm sometimes analyses the sounds of the film and transforms them into a musical version: it attempts to reproduce the original sounds using only the sounds that can be produced by the instruments of a symphony orchestra. A bit like the birdsong in the gallery, the film becomes a place where musical or noisy variations emerge. Constructed on the idea of constraint and enclosure, this film is also a place where something is created…

Is this very present observation on animals associated with biology and nature or does it enable you to allow a slightly wilder form of expression to emerge?

When I first became interested in the history of the museum, I was looking more at the history of the art museum, such as in my film Contre-histoire de la séparation (2010, with Vincent Normand), but very quickly the zoo interested me as a specific museum. On the one hand because it seems more accessible – it is a place for childhood – but it is also more complex – it displays sentient beings even if it only collects their genetic heritage. More broadly speaking, I have always been very interested in biology, particularly because the great question of art appears to me to be that of metamorphosis. How does a structure creating forms take shape and transform itself? In a context governed by algorithms that can produce infinite variation, we must not be fooled: variation is not an emancipation, it is a freedom that is absolutely constrained. For a real metamorphosis, it is necessary to change the rules that govern the processes of transformation: to transform the transformation itself.

Étienne Chambaud, Nameless, 2020 (detail). Donkey, dog, cat and mouse urine, bronze powder, acrylic medium and varnish on canvas, 200 × 150 × 3 cm. Courtesy the artist and Esther Schipper, Berlin. Photo: Andrea Rossetti.

In conjunction with the LaM exhibition, Étienne Chambaud’s first monograph was published by Éditions Dilecta/LaM, with texts by Étienne Chambaud, Tristan Garcia, Mihnea Mircan, Vincent Normand and Filipa Ramos.

‘Lâme’, LaM, 1 All. du Musée, 59650 Villeneuve-d’Ascq, France, 7th October 2022 to 22nd January 2023.

‘Expansion’, Esther Schipper Gallery, 16, place Vendôme, 75001 Paris, France, 19th October to 2nd December.

Head image : Exhibition views, Étienne Chambaud, « Inexistence », Esther Schipper, Berlin, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Esther Schipper, Berlin. Photos : Andrea Rossetti.

Related articles

Céline Poulin

by Andréanne Béguin

Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Interview with Warren Neidich

by Yves Citton