Interview with Katerina Gregos

Art is always about taking position.

Katerina Gregos is the artistic director of ΕΜΣΤ, the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens since the summer of 2021. She is a strong believer of art that surprises by changing perceptions and challenging the given. She sustains that artists can be the missing conscious of society. For her, artistic practice has much to do with the correction of historiography by giving visibility to oppressed and marginalized narratives and by going against historical amnesia.

She served in directorial positions for both private and public institutions (Deste Foundation’s Centre for Contemporary Art, Athens ; Argos – Centre for Art & Media, Brussels ; Art Brussels). She has curated numerous large-scale international exhibitions and nine international biennials. Most recently she was chief curator of the 1st Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art (RIBOCA1). Gregos has also curated three National Pavilions at the Venice Biennale: Denmark (2011), Belgium (2015), Croatia (2019). Apart from her activities as an independent curator since 2016 she is curator of the visual arts programme of the non-profit, Munich-based Schwarz Foundation. She regularly publishes on art, artists, society and culture, in books, catalogues, and periodicals.

Anna Kerekes: It is a great honor to start a conversation with you today. Being a curator and a researcher myself, grounded in the heritage of the Eastern European region, but also having interests in the research based practices and artistic knowledge production, as well as in the field of moving images and lens based media, your career is a true inspiration for me. As for curators, you operate with the following ethical criteria: 1) the role of a curator is to provide the best conditions of presentation and commission of artworks (being payed is one of the basics); 2) a curator has to create opportunities for exchange between local and international artists as part of the sustainability of international projects (so the presence on site is key for rooting the projects before and even after the exhibitions); 3) curatorial concepts has to come from the artworks first and has to be balanced with the theoretical narrative to create a successful show. These are very strong statements in my point of view, both for the definition of art, the role of artistic practice and the ethical dimensions of curating. Could you tell me first what are the origins of these assumptions? Of course, it took more than 30 years to verify them on the ground. But I was wondering, do they come from your family heritage (Balkans?), from your education (history of art, philosophy, museology and museum management) or later, from the encounter of an artist (Oscar Wilde?)? Certainly, they do not belong to the art world. So, where does it all start for you as far as you remember?

Katerina Gregos: I always saw art as part of a wider context, whether social, political, geographical or cultural and was never into art-for-art’s sake. I grew up in an environment with opinionated parents where hot debates were always ongoing. My father was very socially and politically minded, and my mother was a 60’s flower child, so the former was into issues of social justice and egalitarianism and the common good, the latter had a very libertarian view on life and was a very progressive and emancipated woman. From my grandparents, I learned about the experience of World War II, in a very vivid manner. And at school I was especially interested in the theory of knowledge. All of that has shaped the way I see art and work as a curator.

AK: Identity has always been a key notion in your curatorial practice, less for defining individuals than for raising consciousness on marginalized communities. Your exhibition on the Mediterranean sea (13,700,000 km3), on feminism (Fusion Cuisine, 2002), on democracy and borders (Leaps of Faith, 2005), on colonization (Belgian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, 2015) lead us today to the issue of migration, of equality between genders and races, and also to the statecraft, title of your last group show at EΜΣΤ. Do you agree that identity is a seminal notion for you? Could you tell us more about how you approach it recently?

KG: It is cultural identity that particularly interests me, and how this is shaped and constructed. Recently this aspect of identity has also played a key role in the narrative we have explored to construct a renewed mission and direction for EMΣT Athens, in particular its identity as an institution. At a time of institutional crisis and the dominance of the globalist, one-size-fits-all franchise museum model, EMΣT will carve out its own position, true to the hybrid identity of Greece, which has been shaped both by Eastern or Levantine as well as European and Western influences. Taking advantage of its location in a dynamic and multicultural Mediterranean metropolis such as Athens, we will focus on the rich and contested histories of the geographical space it is a part of; a space which includes the Balkans, Turkey, the Middle East and North Africa. Here, cultures, diasporic currents and religions merge and confront each other, yielding rich and often unknown, forgotten or marginalised narratives. Acknowledging the impossibility of inclusivity of all contemporary art, we will look into the museum’s own regional historical, political and cultural inheritance, and its multiple narratives. While ΕΜΣΤ showcases international art but we will also seek out, support and promote contemporary Greek art, which is largely unknown outside the borders of the country, by raising awareness of Greek artists through solo exhibitions and other events and by fostering international exchange. At the same time, the museum will focus on the rich artistic and avant-garde legacy of the Greek diaspora, one of the archetypal global diasporas, a large part of which has never been acknowledged, or even deliberately marginalised in Greece itself.

AK: In a Q&A online you said once that inclusion and curating are notions which are difficult to put together because curating means to select. As a lecturer at HISK: the Higher Institute of Arts in Ghent, and the Jan Van Eyck Academy, in Maastricht, what is your take on wokeism?

KG: What is being defined now as “wokeism” is problematic for several reasons. The first of course is that one must be very diplomatic in addressing any concerns as anything can and may be taken out of context and social media vultures will capitalise on this. It can be challenging to maintain a critical, open and progressive stance that is not always woke-conformist, and as a result, the culture it has created is not often challenged by liberal voices. Another concern it raises is that wokeism comes from an Anglo-Saxon ideology, which is being transplanted into other cultures regardless of their own histories, issues, sensibilities; some could describe it as a form of coercive ideological colonialism. At the moment, this culture determines much of the content in the art world today and anything that is outside it is marginalised. This has created a kind of mono-culture of narratives on race, decolonisation, gender, and while these are inarguably very important causes, there are also other urgent issues. I am in favour of inclusion and against any form of discrimination, I support all minority rights, however, there is something authoritarian about some aspects of wokeism. Cancel culture for example is abhorrent; I consider it to be a violent form of person-annihilation, for want of a better word. So while I am very happy to see that wokeism has facilitated the exploration of a range of narratives and the inclusion of diverse and often marginalised voices, I am also concerned about the lack of nuance and hypocrisy that has come with it.

AK: Despite the group show, Statecraft, you are recently more engaged in the presentation of monographic and individual approaches as the artistic director of EΜΣΤ since 2022. EΜΣΤ presents this year a solo show from Antonis Pittas and Eirini Vourlomnis, Jennifer Nelson at work, Stephan Goldrajck’s work in situ and Dimitris Tsoumplekas’ artic production extra muros. Your latest, independent curatorial practice is more known from group shows (travelling exhibitions, biennales, festivals) and collective approaches (with multiple institutions and association, even co-curating). How do you see your interest evolved by making the programming of this institution in particular?

KG: In fact, large group exhibitions remain a main point of focus for my curatorial practice, so Statecraft (and beyond), which is my first large curatorial exhibition with 39 artists is still very much in line with my focus on thematic groups shows, that I became known for as an independent curator, and this is something I will continue to do. Working in a museum, however, is a completely different context and both types of exhibitions are necessary. Group shows because they develop rich parallel narratives, and solo shows because it gives one the chance to get to know an artist in depth. Within the museum’s artistic programme, there will always be solo shows, and in the future, monographic exhibitions, but I am a big believer in the narrative richness offered by group shows and the encyclopaedic, polyphonic possibilities they can evoke. Also, group exhibitions lend themselves very well to tackling major issues of the day as well as providing multiple perspectives on them. The next exhibition cycle also features another significant group exhibition MODERN LOVE (or Love in the Age of Cold Intimacies).

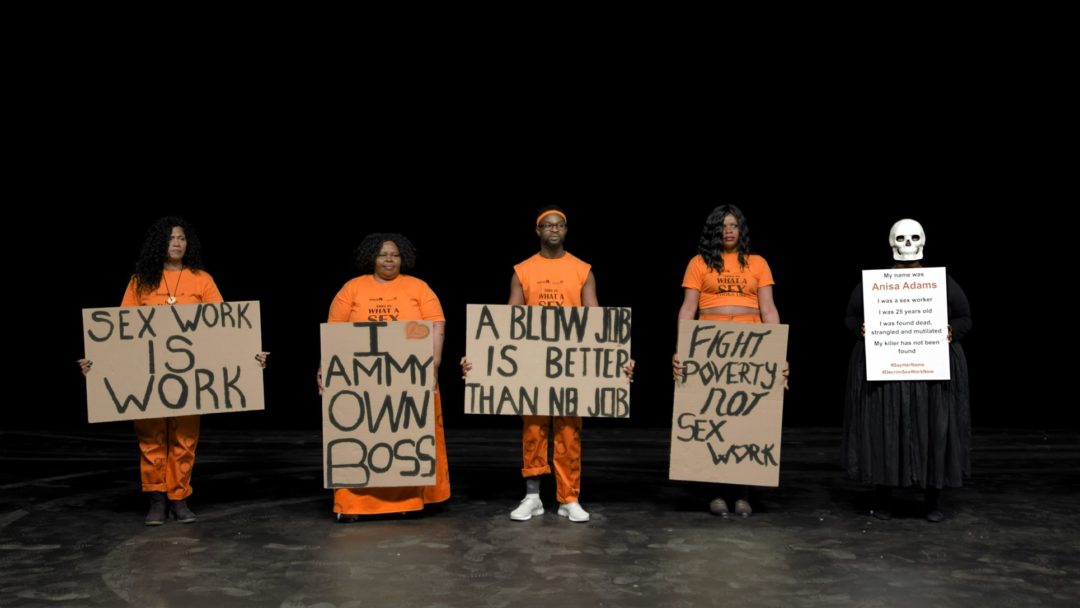

13-Channel Video Installation (Room A: Three-Channel Projection, 6’ loop | Room B: 10 Interviews on Monitors 12 hrs, loop)Ed. 5 + 2 A.P. Commissioned by the B3 Biennial of the Moving Image, Frankfurt am Main © Courtesy of the artist

AK: Do you feel a blackflash to your experiences at Deste Foundation in Athens (1997-2002), Argos Center for Art and Media in Brussels (2006-2008) or the Schwarz Foundation (2016-present)? What kind of opportunity gives you this position, or to put it differently, what kind of artistic vision are you developing for EΜΣΤ?

KG: I’ve been very lucky to work in different institutions, public and private, in Greece and abroad.

Each was different. EΜΣΤ is by far the biggest challenge by virtue of its sheer size (20.000 square metres) and because it is a relatively new museum that has only recently begun to carve out a history. Firstly, it’s important to note that ΕΜΣΤ Athens is a 21st-century museum. It was only founded in 2000. It occupies a very distinctive geographic and geopolitical space and this is something that has played a role in determining the vision, together with my own curatorial interest in artists working with social and political issues. Our aim is to carve out a distinct position in the international museum ecosystem by reflecting its rich geopolitical space at the nexus of East and West.

We don’t want to mimic Western mainstream institutions. Someone coming to see a museum of contemporary art in Athens does not want to see the same things they have seen in London, Paris, Amsterdam, or Berlin. To this end, we are shifting to a longer-term focus on artists from the MENA, Turkey, and the Balkans. It’s an organic development, as we have the good fortune of being neighbours with these regions and also having a Mediterranean identity. This part of the world is culturally, politically and religiously one of the richest and also the most contested, and these histories have not been properly dealt with.

EΜΣΤ is a 100% publicly funded institution at an arm’s length – there is no government or private interference. This is an incredibly luxurious position – and a necessity. While it comes with some difficulties it is also an enormous position of privilege, free of private interference. I believe that a public museum like ours must have a social and educational function, which today consists of promoting awareness of political, social and environmental issues, producing knowledge outside the mainstream circuits, and also supporting artists. This is why we announced that we will be paying all artists who work for or in the museum, regardless of what kind of work they exhibit or produce.

Os Humores Artificiais / Artificial Humors, 2016 (video still)

Single-channel video, colour, sound, 29΄

Courtesy of Galeria Francisco Fino, Lisbon

AK: Your curatorial projects can be read as interdisciplinary research projects. Your interest in the socially engaged and political art is always challenged by your findings in sociology (Marcel Mauss for Give(a)way in 2006 and Alexei Yurchak for Everything was Forever Until it was No Longer at the 1st Riga Biennal in 2018), in human rights (Newtopia in 2012), in economic contracts (Liquid Assets) and lately in the melting spot of new technologies and psychology (Modern Love. Or Love in the Age of Cold Intimacies, 2020-2021). What is the scientific field that influences you most recently, if scientific?

KG: There are many disciplines and fields of enquiry I am interested in from social anthropology to ethnography, history and philosophy. But recently I am becoming more and more interested in technology, not per se, but in relation to everything it determines, influences and shapes. I have been for some time very interested in its effects on society, how digitalisation is changing our social sphere, our interactions, our modes of connection and creation. While the accessibility of the internet to an ever-greater number of people has had liberating and empowering effects, the impact of the technology giants and neo-liberal practices have had a chilling effect, influencing the way we interact with one another. In December, we launch our next exhibition programme with the large international group exhibition, MODERN LOVE (or Love in the Age of Cold Intimacies). Curating this exhibition offered me an opportunity to explore this preoccupation with the effects of technology. I was curious about how the state of love and intimate relationships were evolving in the age of the internet, social media and high capitalism – an age, sociologist Eva Illouz has called “cold intimacies”. There’s the dissolution of inter-personal orthodox conventions and social constrictions, the advent of more open varieties of lifestyles, and the crumbling taboos and biases around gender and sexuality which have liberated human choice in matters of the heart. However, we also live in a time that philosopher Byung-Chul Han has labelled “emotional capitalism”, where human emotions have been co-opted by market forces. The dating supermarkets of Tinder and Grindr, “speed dating” and the ease of internet exchange – apart from offering possibilities – have also hollowed out relationships and led to selfish or narcissistic forms of behaviour and misleading images of the self, making it ever more difficult to establish what is real, meaningful or true.

AK: Last, but not least, in France, you’ve been rapporteur for the Prix Marcel Duchamp in 2018 for the Franco-Vietnamese artist, Thu-Van Tran and curated A World not Ours at la Kunsthalle Mulhouse in 2017. Do you have any “liaisons dangereuses” with the French art scene?

KG: My connection with the French art scene has been via the projects I’ve collaborated on, for example, as you mention, the Prix Marcel Duchamp and the exhibition at the Kunsthalle Mulhouse A World Not Ours. Prior to taking on my role as artistic director in Athens, I was based in Brussels for 16 years, which has a strong international perspective due to its political impetus as the heart of the EU, but what I discovered living there for many years, was that it is also a city that hosts a lot of French artists, many of whom I met while there, and it is very connected to French-speaking diaspora from former colonies like the DR Congo. Living in Brussels also brought me (and still brings me) to Paris very often, where my closest liaisons are the artists that I come to visit or meet.

______________________________________________________________________________

Head Image : EMST © Photo Fotini Alexopoulou

Related articles

Céline Poulin

by Andréanne Béguin

Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Interview with Warren Neidich

by Yves Citton