L.A : …This song makes me want to rob a liquor store*

(L.A : …*) [1]

Je n’ai pas vu l’exposition « Los Angeles 1955-1985 » au Centre Georges Pompidou en 2006. J’étais à Londres, précisément en train finaliser mon départ pour LA, avec en poche les repères d’une vision européenne de la ville et de son histoire artistique récente. LA est aussi la terre d’adoption d’Anaïs Nin. Elle était présente en 1956 pour la lecture de Howl, lorsqu’Allen Ginsberg s’est déshabillé pour défier un spectateur mécontent : la poésie se lit mieux nu. Nudité devenue légendaire et qui fut au point de départ de la rumeur de la répétition de cette « performance » lors de chacune de ses interventions en université. Los Angeles et la Beat Generation, un des hauts lieux du premier grand mouvement de la contre-culture américaine. Un goût pour l’expérimentation, l’excès, la subversion, l’immédiateté, la théâtralité et la fiction qui se retrouvent comme un fil rouge d’année en année. Comment rêver destination plus idéale pour commencer une carrière de jeune curateur ? J’utilise ici le « je » pour deux raisons. D’abord parce que, de l’après-guerre à aujourd’hui, l’histoire de la production artistique à Los Angeles est si dense et si complexe qu’il serait bien impossible d’en proposer une vision générale et critique dans un texte court. Ensuite, parce que Los Angeles est souvent évoquée comme une usine à rêves.

Armando Cabrera Méchicano 72, 1972. Sérigraphie / Silk-screen print, 70 x 58 cm. © The artist. Courtesy UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center, Los Angeles.

La capacité de cette ville à faire rêver s’accompagne de nombreux stéréotypes et fantasmes qui, au cours des années, ont nourri la vision de cette scène artistique dans les discours critiques, dans les expositions et le marché. LA est souvent représentée dans une dualité extrême entre paradis exotique et cauchemar. Hollywood, Disneyland… Le mythe californien d’un laboratoire où tout est possible : un désert transformé en oasis, une promesse généralisée de prospérité économique et de libertés individuelles. Une ville étourdissante, émancipée des traditions, qui atteint le statut de mythe dans la description qu’en fait Reyner Banham en 1971. Un fantasme qui trouve rapidement sa réponse agressive dans « Los Angeles: Ecology of Evil » publié par Peter Plagens dans Artforum en 1972. Pour ajouter à ce titre évocateur et faire court, il suffit de citer la conclusion de Plagens : « the trouble with Reyner Banham is that the fashionable sonofabitch doesn’t have to live here. » Je me garde de traduire. Plagens parle d’ennui et de marasme. On pense à Bukowski. Les images d’un enfer de freeways congestionnés, de tensions raciales, de criminalité et d’imminentes catastrophes naturelles et écologiques persistent dans les ouvrages de Mike Davis publiés dans les années 1990-2000. Cette dualité a accompagné les grandes expositions qui ont posé les jalons de la définition d’une spécificité artistique à Los Angeles : « LA, hot and cool, the eighties » au MIT List Visual Arts Center en 1987 puis, en 1992, « Helter Skelter: L.A. Art in the 1990s » organisée par Paul Schimmel. Cette dernière reprend le titre de la chanson des Beatles que Charles Manson a pris comme référence à sa définition de guerre raciale apocalyptique justifiant sa campagne de crimes. Et, en 1997 « Sunshine & Noir: Art in L.A. 1960-1997 » au Louisiana Modern Art Museum. Si toute tentative de définition est difficile, c’est d’autant plus le cas pour Los Angeles. On s’inscrit de suite dans la simplification et la distorsion d’une réalité et d’une histoire qui se construisent dans la diversité.

Les discussions sur l’art produit à Los Angeles ont également été attachées à une rivalité East Coast / West Coast elle-même ancrée dans un discours obsolète opposant centre et périphérie. LA a longtemps été décrite comme une école régionale où l’orthodoxie de l’avant-garde new-yorkaise déteignait à grands coups de soleil californien, d’esprit adolescent et de dilettantisme généralisé. Le stéréotype était celui d’un manque de sérieux intellectuel et d’une approche intuitive de la création. La vidéo East Coast-West Coast (1969) de Robert Smithson et Nancy Holt en est exemplaire, on y voit Smithson jouant le rôle de l’artiste californien : « Je ne lis jamais de bouquins ; je sors et je contemple les nuages. (Il s’adresse à Holt, jouant l’artiste new-yorkaise) : Pourquoi tu n’arrêterais pas un peu de penser pour commencer à ressentir ? »

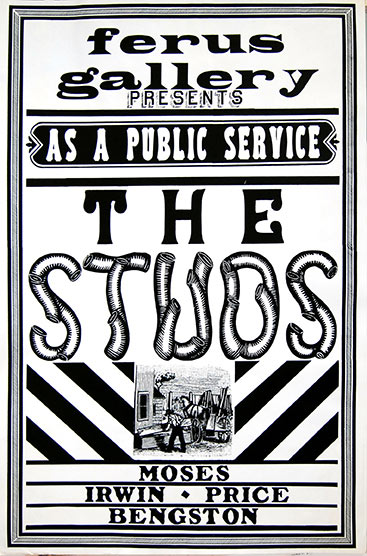

Affiche de l’exposition des Studs à la Ferus Gallery, Los Angeles, 1964 / Poster for The Studs group exhibition at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles, 1964. Courtesy Hal Glicksma

Ce stéréotype naît avec le mythe de la Cool School défini par Philip Leider dans Artforum à l’été 1964. Il est lié à celui des Ferus studs qui, de 1957 à 1966, ont quasiment personnifié le récit de la transformation d’une scène artistique balbutiante en un épicentre (des « studs », c’est-à-dire des étalons… Jay DeFeo étant la seule femme officiellement associée au groupe). Ed Kienholz y côtoyait entre autres Craig Kauffman, John Altoon, Billy Al Bengston, Ed Moses, Robert Irwin, John Mason, Kenneth Price, Llyn Foulkes, Larry Bell, et la figure du père curator : Walter Hopps. Ferus a été le lieu de l’unique exposition personnelle de Wallace Berman en 1957 et celui de son arrestation légendaire pour délit d’obscénité. La galerie fut aussi le lieu de la première exposition personnelle d’Ed Rusha en 1963. Avec Irving Blum, à partir de 1958, la programmation s’étend à la côte est avec Frank Stella, Joseph Cornel, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein et, en 1962, la première exposition personnelle californienne d’Andy Warhol qui y dévoile les Campbell’s Soup Cans. Une effervescence chroniquée par le jeune magazine Artforum qui s’établit à l’étage en 1965. Si les artistes de la Ferus représentent une diversité de voix et symbolisent les débuts de l’émergence d’une scène artistique, la critique a surtout cantonné le LA Look au mouvement minimaliste Light and Space et à ce que les critiques new-yorkais ont péjorativement appelé le Finish Fetish : Kauffman, Al Bengston, Bell, Irwin, John McCracken, DeWain Valentine, Dough Wheeler, mais aussi, et rarement citées, Judy Chicago, Maria Nordman, Mary Corse. Le terme « fétichiste » se référait aux sculptures géométriques à la surface polie et colorée constituées de matériaux provenant de l’industrie de pointe locale (entre autres, l’aérospatiale et le divertissement). L’utilisation du plexiglas, des résines polyuréthane, de la fibre de verre et du plastique correspondait à une investigation des techniques doublée d’un intérêt prononcé pour la culture vernaculaire des Hot Rods, de la customisation et du surf. Le caractère superficiel et l’attrait pour le brillant sont sans doute parmi les stéréotypes les plus vicieux liés à l’art de Los Angeles. On a omis de considérer la complexité de ce mouvement dans son entier et négligé de penser qu’il s’agissait d’intentions sans lien avec le développement régional d’un modèle référent. L’utilisation expérimentale des matériaux visait à une exploration de la lumière et de la perception associée à la recherche d’une expérience concrète du réel, qu’il soit quotidien ou métaphysique.

Harry Gamboa Jr. First Supper After a Major Riot, 1974. Photographie couleur / Color photograph. De gauche à droite / From left : Patssi Valdez, Humberto Sandoval, Willie Herrón III, Gronk dans une performance d’Asco / in the Asco performance piece. Avec l’autorisation d’Harry Gamboa Jr. / Reproduced by permission of Harry Gamboa Jr. © The artist. Courtesy UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center, Los Angeles.

Revenons un instant à l’exposition du Centre Georges Pompidou. À Los Angeles, les avis étaient tranchés : d’une part, la reconnaissance du soutien historique des curateurs européens face à l’absence d’évaluation locale et nationale et, d’autre part, une frustration causée par les lacunes dans une présentation certes centrée autour de travaux de grande qualité mais surtout des stars habituelles. On notait également l’absence d’une contextualisation claire révélant les liens entre les artistes, les micro-scènes, les lieux et la diversité culturelle et ethnique de la ville. Et même en se cantonnant aux figures connues, comment classifier des pratiques résistant aux catégories ? Quel est le lien entre les céramistes d’Otis et le mouvement Art and Space ? Comment comprendre la transition de la génération de Venice vers une approche plus conceptuelle du divertissement de masse caractérisant certains artistes de la génération suivante comme Bas Jan Ader ou Ger van Elk ? Quelle a été l’influence réelle de Sister Corita sur ces artistes et sur la génération de Mike Kelley ? Où situer les pratiques complexes de Judy Chicago, Jack Goldstein, ou encore Bill Leavitt ? Les années soixante-dix voient l’essor de CalArts et d’Irvine et l’influence de l’enseignement de Kaprow, Antin et Baldessari. Ce second développement conduit la scène artistique vers son statut de référence internationale dès les années quatre-vingt. Cependant cette histoire continuait à s’écrire de façon lacunaire et blanche. Voici donc les bases de la vision européenne que j’avais en poche.

En 2006-2007, j’ai passé beaucoup de temps à downtown, et notamment au 727 Spring Street où Adrian Rivas avait créé un lieu alternatif. J’y ai rencontré la communauté intellectuelle et artistique issue de East LA. Le bâtiment appartenait à Gronk, un homme d’environ cinquante ans qui semblait avoir un Street Credit démentiel. « C’est un des fondateurs d’Asco » m’a-t-on dit. De qui ? J’ai alors écouté de façon répétée, mais sans jamais voir une œuvre, le récit de ce collectif (dont le nom espagnol signifie « nausée ») fondé en 1972 par Harry Gamboa, Jr., Gronk, Willie Herrón et Patssi Valdez alors qu’ils étaient encore au lycée. C’était le récit d’une attitude à la fois glamour et punk, d’interventions urbaines et de performances… Un récit relevant quelque part du mythe et de la légende urbaine et s’activant comme une tradition orale dans la parole de jeunes artistes.

Ayant manqué l’exposition du LACMA « Phantom Sightings: Art after the Chicano Movement » organisée en 2008 par Rita Gonzalez, il a fallu que j’attende 2011 et l’initiative Pacific Standard Time organisée par le Getty et comprenant la première rétrospective d’Asco au LACMA : « Asco: Elite of the Obscure, A Retrospective, 1972–1987 ». Elle m’a enfin révélé certaines œuvres dont j’avais entendu tant de descriptions. Rappelons que « Phantom Sightings » avait été la première exposition d’artistes mexicains-américains contemporains depuis 1974 au LACMA, si on ignore les graffitis revendiqués en 1972 par Asco à l’entrée du Musée.

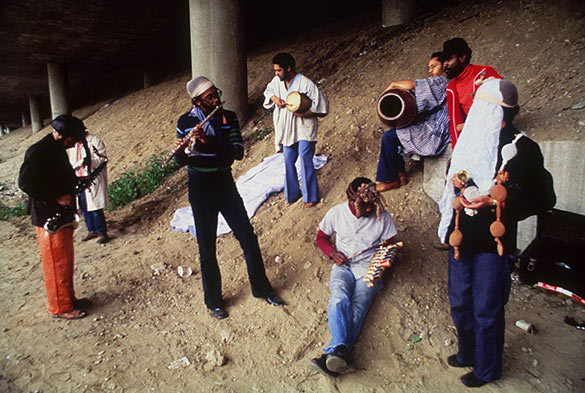

Senga Nengudi Freeway Fets, 1978. C-print, 30 × 45 cm, edition of 5 (+1 AP). Photo : Quaku/Roderick Young, courtesy the artist and Thomas Erben Gallery, New York.

Avec Pacific Standard Time, le Getty inaugurait une révolution copernicienne de l’art américain d’après-guerre. Plus de soixante-dix lieux se sont acharnés à combler les lacunes de l’histoire et à présenter la complexité de l’art produit à Los Angeles et en Californie du Sud de 1945 à 1980. Asco a été présenté dans cinq expositions et analysé selon des contextes et angles critiques divers. Au lieu de créer un effet de canonisation, Pacific Standard Time ébranle les repères chronologiques et révèle la face cachée de l’iceberg : il y a toujours eu plusieurs scènes à LA. Les quelques moments où celles-ci se rencontrent doivent être mis en valeur. Le lieu alternatif LACE était, par exemple, un des points de contact entre la sensibilité CalArts, East LA et la scène punk d’Hollywood. Gronk y était associé depuis le début et inaugura le lieu avec Dreva, en 1978, dans une soirée mémorable intitulée Art Meets Punk. Pour East LA, les cinq expositions organisées par le UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center sous le nom de LA Xicano sont édifiantes. L’une d’entre elles retrace les activités et liens dynamiques entre neuf collectifs, studios et lieux alternatifs de East LA, pour la plupart encore actifs aujourd’hui. Parmi eux, le premier centre d’art Chicano à LA Goez Art Studio (1969), Self Help Graphics (1971), SPARC (Social and Public Art Resource Center (1976), Los Dos Streetscapers (1975-1980) et Mechicano Art Center (1969-1978). Tout comme Asco, ces groupes s’inspiraient souvent des conditions de vie mexicaines-américaines à LA. D’autant que cette réalité était violente, ponctuée par le racisme et la brutalité policière. Pour « First Supper (After a Major Riot) », Asco retourne à Whittier Blv et Arizona St en 1974 et plante une scène de dîner festif entre deux voies routières. Il s’agit du lieu de l’assassinat du journaliste Ruben Salazar par la police trois ans plus tôt pendant le Chicano Moratorium. Dans ce contexte de tension et de répression, les actions d’Asco sont rapides et quasiment invisibles. Elle sont souvent conçues comme des « No Movies » : une image extraite d’un film non existant. La pratique de la fresque y rejoint celle de la performance, de la photographie et du film, tout en mettant l’accent sur une célébration identitaire s’appropriant avec désinvolture le glam hollywoodien.

Le journalisme de Salazar comparait souvent l’esprit identitaire Chicano à celui de la lutte pour les droits civiques des Africains Americains. La révolte de Watts Tower en 1965 avait révélé des revendications qui ne se limitaient pas à South LA. Le fameux projet de Noah Purifoy « 66 Signs of Neon » en 1966 avait d’ailleurs dépassé les lignes raciales. Comme l’a montré l’exposition du Hammer « Now Dig This ! Art and Black Los Angeles 1960-1980 », les artistes chicano et africains américains partageaient une même invisibilité et étaient, pour beaucoup d’entre eux, engagés dans une forme d’activisme politique qui favorisait les rencontres. Quelle que fût leur situation géographique, les centres d’art alternatifs partageaient une réalité. Dans les années soixante-dix, l’artiste Andrew Zermeño de Mechicano Art Center collabore par exemple avec l’artiste africain américain John Outterbridge qui, à partir de 1975, devient le premier directeur de Watts Art Center. La nature underground et les processus de travail collaboratifs et quasi rituels d’Asco pourraient être mis en parallèle avec les expérimentations du collectif Studio Z qui rassemble notamment David Hammons, Maren Hassinger, Ulysses Jenkins et Senga Nengudi. En 1978, avec « Ceremony for Freeway Fets », cette dernière organise et documente, elle aussi, une cérémonie sur le bord d’une route, ou plus précisément sous un pont de freeway. Malgré quelques images d’archives, la mémoire de cette performance improvisée sous forme de rituel collectif, avec musique et costumes, vit surtout dans la tradition orale.

« Los Angeles existe dans un environnement désertique hautement volatil qui a généré des mirages et des mythes absolument séduisants. Mais les freeways créent un effet de spirale étourdissant, où il est encore possible d’entrevoir une vue non stéréotypée » [2]

- ↑ Titre © Hugo Hopping, 2009.

- ↑ Harry Gamboa Jr., in « L.A Stories, A roundtable discussion », Artforum, Octobre 2011, p .242.

L.A : …This song makes me want to rob a liquor store*

(L.A : …*) [1]

I did not see the exhibition “Los Angeles 1955-1985” at the Centre Georges Pompidou in 2006. I was in London, as it happens in the process of finalizing my departure for L.A., with the landmarks of a European vision of the city and its recent artistic history in my pocket. L.A. is also Anaïs Nin’s adopted home. She was there in 1956 for the reading of Howl, when Allen Ginsberg took his clothes off to challenge an unhappy spectator: poetry is better read naked. A nakedness that became legendary and kicked off the rumour that that “performance” would be repeated at each one of his university appearances. Los Angeles and the Beat Generation, one of the hubs of the first major movement of the American counter-culture. A liking for experimentation, excess, subversion, immediacy, theatricality, and fiction, which recur like a thread from year to year. How could anyone dream of a more ideal destination for embarking on a career as a young curator? I am using the “I” here for two reasons. Firstly because, between the postwar period and the present-day, the history of artistic production in Los Angeles has been so dense and so complex that it would be quite impossible to propose a general and critical view of it in a short essay. Secondly, because Los Angeles is often talked about as a dream factory.

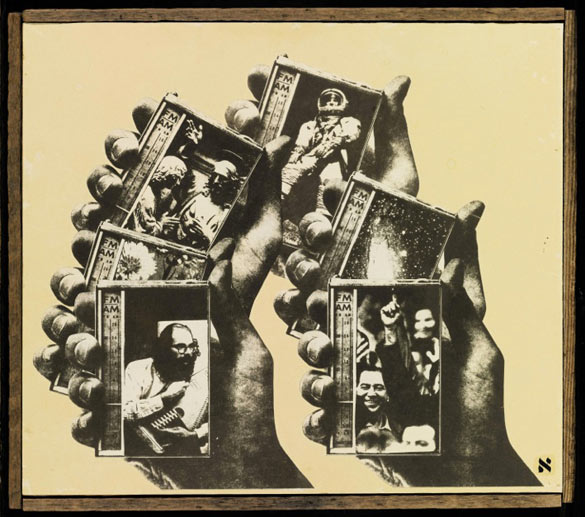

Wallace Berman Untitled (Shuffle piece), 1960. Verifax collage, 29 × 33 cm, pièce unique. Courtesy The estate of the artist and galerie Frank Elbaz, Paris.

This city’s capacity to make people dream goes hand in hand with many stereotypes and fantasies which, over the years, have fuelled the vision of this art scene in critical argument, in exhibitions, and on the market. L.A. is often depicted as an extreme duality somewhere between exotic paradise and nightmare. Hollywood, Disneyland,… The Californian myth of a laboratory where everything is possible: a desert turned into an oasis, an overall promise of economic prosperity and individual freedoms. A mind-blowing city, liberated from traditions, which achieves mythical status in Reyner Banham’s description of it in 1971. A fantasy which swiftly finds its aggressive response in “Los Angeles: Ecology of Evil”, published by Peter Plagens in Artforum in 1972. To add to this evocative title and not waste words, it will suffice to quote Plagens’s conclusion: « the trouble with Reyner Banham is that the fashionable sonofabitch doesn’t have to live here. » Plagens talks about boredom and depression. One thinks of Bukowski. Images of a hell made up of congested freeways, racial tensions, criminality, and imminent catastrophes, natural and ecological alike, all recur in Mike Davis’s books published in the 1990s and 2000s. This duality has gone hand in hand with the major exhibitions which have staked out the definition of a specific artistic factor in Los Angeles: “L.A., Hot and Cool, the Eighties” at the MIT List Visual Arts Center in 1987, then, in 1992, “Helter Skelter: LA Art in the 1990s”, organized by Paul Schimmel. This latter show borrowed the title of the Beatles’ song which Charles Manson used as a reference for his definition of apocalyptic race war, justifying his campaign of crimes. And, in 1997, “Sunshine & Noir: Art in L.A. 1960-1997” at the Louisiana Modern Art Museum. If it is hard to define anything, this is all the more so with Los Angeles. One consequently becomes part of the simplification and distortion of a reality and a history which are constructed in diversity.

Discussions about the art produced in Los Angeles have also had to do with an East Coast/West Coast rivalry, itself rooted in an obsolete discourse contrasting centre and periphery. L.A. was for a long time described as a regional school, where the orthodoxy of the New York avant-garde became bleached out with bouts of Californian sun stroke, and a general teenage and dilettante spirit. The stereotype was one of a lack of intellectual seriousness and an intuitive approach to creation. The video East Coast-West Coast (1969) by Robert Smithson and Nancy Holt is a good example of this. In it we see Smithson playing the role of the Californian artist: “I never read books; I just go out and look at the clouds. (He is talking to Holt, playing the New York artist). Why don’t you stop thinking and start feeling?”

This stereotype came into being with the myth of the Cool School defined by Philip Leider in Artforum in the summer of 1964. It is connected with the stereotype of the Ferus studs which, between 1957 and 1966, more or less personified the narrative of the transformation of an art scene in its infancy into an epicentre (« studs », , meaning stallions… Jay DeFeo being the only woman officially associated with the group).In it Ed Kienholz rubbed shoulders with, among others, Craig Kauffman, John Altoon, Billy Al Bengston, Ed Moses, Robert Irwin, John Mason, Kenneth Price, Llyn Foulkes, Larry Bell, and the curator-cum-father figure of Walter Hopps. Ferus was the site of Wallace Berman’s only solo show, held in 1957, and the place of his legendary arrest for obscenity. The gallery was also the venue for Ed Ruscha’s first solo exhibition in 1963. With Irving Blum, from 1958 on, the programme spread to the East coast with Frank Stella, Joseph Cornell, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, and, in 1962, Andy Warhol’s first solo Californian show, at which he unveiled his Campbell’s Soup Cans. An effervescence chronicled by the young magazine Artforum which set up shop above the Ferus gallery in 1965. If the Ferus artists represented a diversity of voices and symbolized the beginnings of the emergence of an art scene, the critics reduced the LA Look to the Minimalist movement Light and Space and to what New York critics derogatorily called the Finish Fetish : Kauffman, Al Bengston, Bell, Irwin, John McCracken, DeWain Valentine, and Doug Wheeler, but also, if rarely mentioned, Judy Chicago, Maria Nordman, and Mary Corse. The term “fetishist” referred to the geometric sculptures with their polished and colourful surfaces, made of materials coming from local state-of-the-art industry (among others, the aerospace and entertainment sectors). The use of Plexiglas, polyurethane resins, fibre glass and plastic tallied with an investigation into techniques, compounded by a pronounced interest in the vernacular culture of Hot Rods, customization, and surfing. The superficial character and attraction to glitz are probably among the most snide stereotypes associated with Los Angeles art. People have forgotten to think about the complexity of this movement in its entirety, as they have neglected to think that what was involved was intentions which had no connection with the regional development of a referent model. The experimental use of materials was aimed at an exploration of light and perception associated with the quest for a tangible experience of reality, be it everyday or metaphysical.

Oscar Castillo Shrine to the Virgin of Guadalupe at Maravilla Housing Projects, Mednik Avenue and Brooklyn Avenue, East Los Angeles, early 1970s. Photographie couleur / Color photograph. © The artist. Courtesy UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center, Los Angeles.

Let us come back for a moment to the exhibition at the Centre Georges Pompidou. In Los Angeles, opinions were divided: on the one hand, an acknowledgement of the historical support of European curators in the face of the absence of any local and national evaluation, and, on the other hand, a frustration caused by the gaps in a presentation definitely focused on works of great quality, but also on the usual stars. People also noted the absence of any clear contextualization revealing the links between artists, micro-scenes, venues, and the city’s cultural and ethnic diversity. And even by sticking with known figures, how were activities which resisted pigeonholing to be classified? What is the link between the Otis ceramicists and the Art and Space movement? How were people to understand the transition of the Venice generation towards a more conceptual approach to mass entertainment, typifying certain artists belonging to the following generation, such as Bas Jan Ader and Ger van Elk? What was the real influence of Sister Corita on these artists and on the Mike Kelley generation? Where are we to situate the complex activities of Judy Chicago, Jack Goldstein, and Bill Leavitt? The 1970s saw the booming development of CalArts and Irvine, and the influence of the teaching of Kaprow, Antin and Baldessari. This second wave of development took the art scene towards its status as an international reference in the 1980s. However, this history was still being written in a incomplete and blank way. These , then, were the foundations of the European vision that I had in my pocket.

In 2006-2007, I spent a lot of time downtown, and in particular at 727 Spring Street, where Adrian Rivas had set up an alternative venue. At it, I met the intellectual and artistic community coming from East L.A. The building belonged to Gronk, a man of about 50 who seemed to have outrageous street creds. “He is one of the founders of Asco”, I was told. Founder of what? I then repeatedly, but without ever seeing a work, listened to the story of that collective (whose Spanish name means “nausea”) founded in 1972 by Harry Gamboa Jr., Gronk, Willie Herrón and Patssi Valdez, when they were still in high school. It was the story of an at once glam and punk attitude, a tale of urban activities and performances… USomewhere, it came from myth and urban legend, taking the form of an oral tradition in the words of young artists.

Having missed the LACMA show “Phantom Sightings: Art After the Chicano Movement”, organized in 2008 by Rita Gonzalez, I had to wait until 2011 and the Pacific Standard Time programme organized by the Getty and including the first Asco retrospective at the LACMA: “Asco: Elite of the Obscure, A Retrospective, 1972-1987”. It finally showed me certain works which had been so often described to me. Let us bear in mind that “Phantom Sightings” had been the first exhibition of contemporary Mexican-American artists since 1974 at the LACMA, if we disregard the graffiti at the museum entrance, which Asco claimed to have done in 1972.

Senga Nengudi Freeway Fets, 1978. C-print, 30 × 45 cm, edition of 5 (+1 AP). Photo : Quaku/Roderick Young, courtesy the artist and Thomas Erben Gallery, New York.

With Pacific Standard Time, the Getty ushered in a Copernican revolution in postwar American art. More than 70 venues rushed to fill the gaps of history and show the complexity of the art produced in Los Angeles and southern California between 1945 and 1980. Asco was presented in five shows, and analyzed in different contexts and from different critical angles. Instead of creating an effect of canonization, Pacific Standard Time upset the chronological landmarks and revealed the hidden face of the iceberg: there have always been several scenes in L.A. The few moments when these scenes meet need to be highlighted. The alternative place known as LACE was, for example, one of the points of contact between the CalArts sensibility, East L.A., and the Hollywood punk scene. Gronk was associated with it from the start and inaugurated the venue with Dreva, in 1978, in a memorable evening titled Art Meets Punk. For East L.A., the five exhibitions put on by the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center, under the name of LA Xicano were instructive. One of them traced the activities and dynamic links between nine collectives, studios and alternative venues in East L.A., most of which are still active today. Among them were the first Chicano art centre in L.A., Goez Art Studio (1969), Self Help Graphics (1971), SPARC (Social and Public Art Resource Center) (1976), Los Dos Streetscapers (1975-1980) and Mechicano Art Center (1969-1978). Just like Asco, these groups often drew their inspiration from Mexican-American living conditions in L.A. And that reality was a violent one, punctuated by racism and police brutality. For First Supper (After a Major Riot), Asco went back to Whittier Boulevard and Arizona Street in 1974 and set up a festive dinner scene between two thoroughfares. This was the place where Ruben Salazar was murdered by the police three years earlier during the Chicano Moratorium. In a context of tension and repression, Asco’s actions were quick and almost invisible. They were often devised like “No Movies”: an image which seems taken from a film which does not exist. Fresco activity links up here with performance, photography and film, while at the same time emphasizing an identity-based celebration which nonchalantly appropriates Hollywood glam.

Salazar’s journalism often compared the spirit of Chicano identity with that of the civil rights struggle waged by African-Americans. The Watts riots in 1965 had pointed to claims that were not just limited to South L.A. Noah Purifoy’s famous 66 Signs of Neon project in 1966 had also gone beyond racial lines. As shown by the Hammer Museum’s show “Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles 1960-1980”, Chicano and African-American artists shared the same kind of invisibility and many of them were involved in a kind of activism that encouraged meetings. Whatever their geographical location, alternative art centres had one reality in common. In the 1970s, for example, the artist Andrew Zermeño of the Mechicano Art Center worked with the African-American artist John Outterbridge who, in 1975, became the first director of the Watts Art Center. Asco’s underground nature and collaborative and almost ritual work processes might be aligned with the experiments conducted by the Studio Z collective, which included, in particular, David Hammons, Maren Hassinger, Ulysses Jenkins and Senga Nengudi. In 1978, with Ceremony for Freeway Fets, this latter also organized and recorded a roadside ceremony, or, more precisely, a ceremony under a freeway bridge. Despite a few archival pictures, memories of that off-the-cuff performance in the form of a collective ritual, with music and costumes, lives on above all in the oral tradition.

« Los Angeles coexists as a highly volatile desert environment that has produced globally seductive mirages and myths. All the freeways lead to a dizzying spiral effect where it is still possible to catch a glimpse of a non-stereotypical view. » [2]

- ↑ Titre © Hugo Hopping, 2009.

- ↑ Harry Gamboa Jr., in « L.A Stories, A roundtable discussion », Artforum, Octobre 2011, p .242.

articles liés

Anthropocenia

par Benedicte Ramade

Portfolio

par Geoffroy Mathieu et Bertrand Stofleth

Entretien avec Marc-Olivier Wahler

par Patrice Joly