Même les trolls aiment le rock’N’roll

Please scroll down for english version

Depuis quelques années, un projet collaboratif d’édition réalise le BBB, le black book black, en intervenant dans des bibliothèques, de Rogues à Stockholm, de Lausanne à Saint Petersbourg, n’importe. Ils apportent leurs machines, presse et outils de reliures, sortent leurs affaires et fabriquent, page par page, cahier par cahier, un livre à l’impression nue, en noir seul. Très graphique, cette production du même ou presque, cette récurrence, fonctionne comme une sorte de performance, le livre fini est disposé dans la bibliothèque

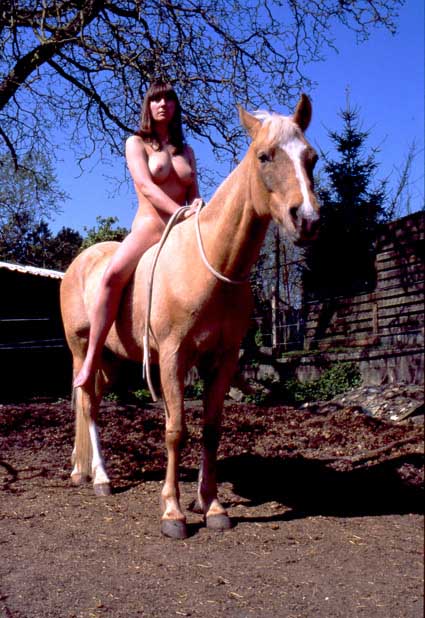

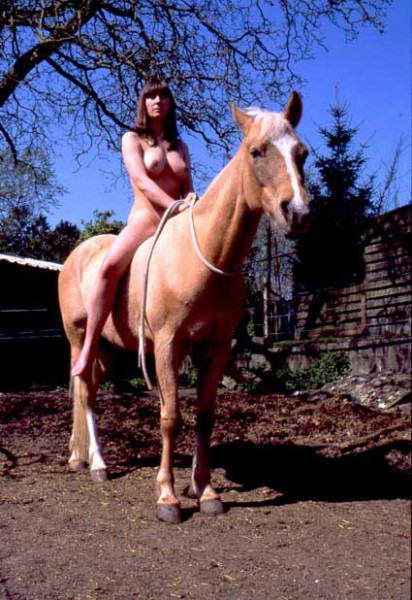

David Évrard, Lady, 2010. Photographie. Dimensions variables. Production Le Confort Moderne, Poitiers.

sans nomenclature, sans référence, le black book se situe dans les rayons au moment où le livre fait basculer l’étagère. Cette pratique de l’édition, qui renvoie au colportage, au conte, au Moyen-Âge de la copie d’une certaine manière est balancée par toute cette économie du noir. Primitif et gras, scénarisé en formats, qualités des papiers, utilisant parfois des références à des ouvrages plus ou moins célèbres, un atlas, un dictionnaire, quelques romans ou aux contextes, comme l’histoire ou la forme de la librairie dans laquelle la performance a lieu, ce sombre d’origine, le truc de l’intérieur, des yeux fermés, de la scriptoria, trouve dans sa réalisation, et à travers cette copie systématique, page noire, page noire, page noire, page noire, un rapport étrange avec, je sais pas… La bonne copie, le moment unique où cette copie là, ici, maintenant, va pouvoir se déployer.

Il y a deux, trois semaines, Benoit Platéus m’a donné son dernier livre paru, tiré à une douzaine d’exemplaires : Mémoires d’un névropathe, de Daniel Paul Schreber aux éditions du Seuil. Il n’y a pas de feinte. Il a « juste » tout décalé d’une page. C’est le même, simplement la page de droite est à gauche, la couverture est faite d’une copie de la première page intérieure. À photocopier un livre entier, le pli intérieur, de fait, est plus sombre (ben oui, sinon vous éclatez la reliure) et dans ce travail de Benoit, eh bien le noir se retrouve sur les bords extérieurs des pages et à la 192 on trouve ceci : « le dessiner (dans le sens de la langue des âmes) consiste en l’utilisation volontaire de la force de l’imagination humaine dans le but de susciter des images (essentiellement des images-souvenirs) en la tête, afin de les y donner à voir aux rayons. Par un effort d’évocation je peux, à partir de tous les souvenirs de mon existence, bêtes et gens, plantes, objets naturels ou usuels de toutes sortes créer des images avec pour effet qu’elles deviennent visibles… »

En 2006 alors que je tenais le JOE DALTON R HOUSE au centre Anspach à Bruxelles, Aline Bouvy me parlait de Lady Godiva, me disait « ce serait bien que je traverse le boulevard nue sur un cheval et que je rentre dans le bar, j’aurais des longs cheveux qui cacheraient mes seins, ce serait super beau ». Difficile d’avoir les autorisations pour qu’un cheval se promène sur les boulevards, à la place on a monté un match de catch dans la boue. Ça a pas mal marché (1). Et cette image m’est restée. D’autant qu’il s’agit d’une histoire à la fois romantique et communarde, puisant dans le Moyen-Âge avec un truc « presque » féministe et où apparaît Peeping Tom, le « regardeur », enfin, en tout cas, ça m’est resté. Ça m’est resté comme un truc dur. J’ai fini par produire cette image.

Robert Johnson a raconté jusqu’à sa mort en 1938 comment il avait vendu, à la croisée de deux sentiers et sous un arbre mort, son âme en échange d’un bon jeu de guitare. Il avait quitté son Juke Joint avec un jeu moyen pour y revenir, six mois plus tard, avec le même jeu, mais du diable. « Nous étions sur la route des jours et des jours, sans argent et parfois sans nourriture, cherchant un endroit décent pour passer la nuit. On jouait dans des rues poussiéreuses et des bars crasseux, et tandis que j’étais à bout de souffle et me voyais vivre comme un chien, il y avait Robert tout propre comme s’il sortait d’une église le dimanche ! » (2). Puis Robert Johnson, grand inspirateur, est rentré dans le cénacle des musiciens morts à 27 ans laissant derrière lui traîner la légende qu’il aurait fabriquée à la suite de quelques bons mots à une époque où le vaudou imprégnait bien les esprits.

With a black cat bone and a mojo tooth.

Il y a dans la production de copie l’idée d’épreuve, de calque, de double ou d’imitation, ce qui s’éloigne subtilement, sans s’en détacher véritablement, de la reproduction. Disons qu’il n’y a pas de copie sans œuvre alors que la reproduction ne subit pas l’original, vous me suivez ? Bon, je ne vais pas rentrer dans un truc sur le faux, l’imitation ou la nature, débat sur lequel je serais bien en peine de tenir une idée vaillante. Ce que je veux dire c’est qu’il y a dans la copie une idée de l’admiration quasi faustienne. Une réfection (3), un refaire.

Pour Lady Godiva, j’ai demandé à Aline si c’était okay pour elle que je fasse le truc, que je le mette à ma sauce. Bien sûr le mythe ne lui appartient pas et des mecs, peintres ou cinéastes, qui ont fait des Lady Godiva, il y en a cinquante. En fait ça n’avait pas de sens, mais je trouvais ça important de lui en parler. Ce n’était pourtant pas une idée originale et j’imagine souvent que les sujets appartiennent à tout le monde, que ce n’est pas ça qui vaut. Mais c’est sur ce principe d’« appropriation originale » – je veux dire, personne ne va plus aller rephotographier des pubs Marlboro, maintenant – que les notions de copie ont dévié. À dire vrai, ce rapport à l’original, au vieux morceau de « l’auteur » nous reste comme un reste d’éducation, une politesse. L’ère de la dimension critique ou célébrée d’images massives de bêtes et gens, plantes, objets naturels ou usuels de toutes sortes est passée. Nous sommes dans la reconsommation. Quelque gestuelle qui aille, et jusque dans l’image de, comment dire, l’expression de la profondeur des choses, de la noirceur ou de la joie, de la déliquescence intérieure, des craintes ou d’un ensemble de sentiments qui fleurent l’abstraction des humeurs et des interprétations, somme toute d’œuvres marquées du sceau de l’émotion (4) il n’y a plus de forme construite qui le soit hors de sa pose. Je veux dire, ça va, on sait ! La reconsommation n’est pas un thème.

C’est que l’emprunt d’un objet à copier ou d’une idée à refaire ou d’une affaire à remonter ne passe par l’utilisation mécanique de la copie comme écho aux industries de l’image que pour soutenir à l’inverse que celles-ci, qui agissent, seraient prêtes à se fendre d’une partition élégiaque et subjective de ce qui compose le geste et derrière, le gusse qui l’a sorti.

Mmmm, the sun goin’ down, boy, dark gon’ catch me here, Oooo, eeee, boy, dark gon’ catch me hère (5), et tout se verse dans un bain de sauces faites de mythes et de rumeurs, de restes, de croyances, de tentatives, plus ou moins frimées, plus ou moins conséquentes et qui pourraient faire voir. Faire voir des trucs, psscchiiii, c’est comme ça. La copie se substitue à la source. Elle est la preuve d’un vocabulaire qui est déjà le travail. C’est une construction générale, pas du sample, pas de la mécanique. La copie, ici, c’est une mixture.

Benoit ne s’est pas habillé de la peau du taré artificiel, dans le journal du névropathe, il en introduit le caractère, il l’exploite, le sort, pas comme un gimmick, mais comme le truc qui parle. Comme un truc qui vient de lui. La copie est autrement investie que la seule reproduction. Ça vous refait, c’est pas la même chose.

Making love to every poor daughter’s son

Isn’t it fun?

Now today, propping grace with envy

Lady Godiva peers to see if anyone’s there

And hasn’t a care. (6)

(1)« Ego devant la mort, ABJG vs SDIP », Joe Dalton n°3 « R House », 2006.

(2) Attribué à Johnny Shines in Robert Johnson, Samuel Charters, Oak Publications, 1963.

(3) En droit, une réfection consiste en le remplacement d’un acte antérieur, nul pour vice de forme, par un actevalable qui ne modifie ni la nature ni l’objet des conventions.

(4) Bruno Munari, cité in Munari – Carte du Ciel, Trinie Dalton, Particules n°27, mars 2010, p. 21.

(5) in Two Roads Blues, paroles de Robert Johnson.

(6) in Lady Godiva’s Operation, Velvet Underground, White Light/White Heat, 1968.

Even Trolls Dig Rock ‘n’ Roll

By David Evrard

For the past few years a collaborative publishing project has been producing the BBB—the black book black—working in libraries, from Rogues to Stockholm and Lausanne to St.Petersburg, wherever. They bring their machines, press and binding tools, get out their things and, page by page, gathering by gathering, manufacture a book that is bare-printed just in black. This very graphic production of the same, or as good as, this recurrence, works like a kind of performance; the finished book is placed in the library without any nomenclature or reference. The black book happens to be in the shelves just when the book makes the shelf tip. This publishing practice, which refers to peddling and hawking, to tales, to the Middle Ages of the copy is, in a certain way, offset by this whole economy of black. Primitive and thick, scripted in formats, and paper qualities, sometimes using references to more or less famous tomes, an atlas, a dictionary, a novel or two, and contexts, like history and the form of the bookshop in which the performance takes place, this original darkness, the thing within, the eyes shut thing, the scriptoria, finds in its execution, and through this systematic copy, black page, black page, black page, a strange relation with, I dunno… The right copy, the unique moment when this particular copy, here, now, will manage to unfurl.

Two or three weeks back, Benoit Platéus gave me his latest book to be published, in an edition of a dozen: Memoirs of a Neuropath, by Daniel Paul Schreber, with Le Seuil. There’s no pretence. He has “just” shifted it by a page. It’s the same, simply that the right page is on the left, the cover is made of a copy of the first inside page. By photocopying a whole book, the inside fold is, de facto, darker (that’s right, if not, you burst the binding) and in this work by Benoit, well, the black is on the outer edges of the pages and on page 192 you find this: “… drawing (in the sense of the language of souls) consists in the deliberate use of the power of the human imagination with the goal of stirring up images essentially memory-images in the head, so as to present them on the shelves”. Through an effort of evocation, based on all the memories of my existence, animals and people, natural and ordinary objects of all sorts, I can create images whose effect is that they become invisible…

In 2006, when I had the JOE DALTON R HOUSE at the Anspach Centrein Brussels, Aline Bouvy told me about Lady Godiva and said: “…it would be great if I crossed the boulevard naked on a horse and went into the bar, I’d have long hair hiding my breasts, it would be really beautiful”. Hard to get permits for a horse on boulevards, so instead we set up a wrestling match in the mud. It worked quite well1 And this image has stayed with me. All the more so because it involves a story that is at once romantic and Communard, drawing from the Middle Ages with an “almost” feminist thing where Peeping Tom appears, the “onlooker”, anyway, in the end, that stayed with me. It stayed with me like something hard. I ended up producing that image.

Right up to when he died in 1938, Robert Johnson told how, at the crossroads of two paths and beneath a dead tree, he had sold his soul in exchange for some good guitar riffs. He had left his Juke Joint playing it so-soand he returned six months later playing just the same, but in one helluva way. We were on the road for days and days, with no money and sometimes with no food, looking for a decent place to spend the night. We played in dusty streets and squalid bars, and while I was at the end of my tether and saw myself living like a dog, there was Robert all clean as if he’d just come out of Sunday church!”.2

Then Robert Johnson, great inspirer, entered the coterie of dead musicians at the age of 27, leaving behind him the legend that he manufactured with a few apt words at a time when minds were being well stacked with voodoo.

With a black cat bone and a mojo tooth

In the production of copies there is the idea of proof, tracing paper, duplicate and imitation, which subtly removes it from the reproduction, but without becoming truly separate. Let’s say that there’s no copy without a work, whereas the reproduction does not suffer the original, if you follow me? Okay, I’m not going to get into a thing about fakes, or imitation, or nature, a debate in which I’d be hard pushed to have any valiant ideas. What I mean is that there exists in the copy an idea of almost Faust-like admiration. A redoing3, a remaking.

For Lady Godiva, I asked Aline if it was okay with her for me to do the thing, make it in my own way. Needless to say, the myth doesn’t belong to her, and there must be 50 guys–painters and film-makers—who’ve made Lady Godivas. In fact it didn’t make sense, but I thought it important to talk to her about it. Yet it wasn’t an original idea and I often imagine that subjects belong to everyone, that that’s not what’s important. But it’s on the principle of “original appropriation”—I mean, no one is going to rephotograph Marlboro ads any more, now—that notions of copy have veered away. If the truth be told, this relation to the original, to the old“auteur” piece,is still with us like a remnant of upbringing, something polite. The age of the critical and celebrated dimension of massive images of animals and people, natural and ordinary objects of all sorts is over. We are in a state of re-consumption. Whatever body language there may be, and even in the image of, how shall I put it, the expression of the profundity of things, of blackness and joy, of inner deliquescence, fears and a set of feelings which skim the abstraction of moods and interpretations, when all is said and done works marked by the seal of emotion4, there is no longer any constructed form that is as much outside its pose. I mean, it’s okay, we know! Re-consumption is not a theme.

The fact is that borrowing an object to copy or an idea to rehash or a thing to put back together does not pass by way of the mechanical use of the copy as an echo of the image industries, except to uphold , conversely, that these latter, which act, are ready to split from an elegiac and subjective score of what composes the gesture and, behind, the bloke emerging from it.

Mmmm, he sun goin’ down, boy, dark gon’ catch me here, Oooo, eeee, boy, dark gon’ catch me here5, and everything pours into a tub of sauces made of myths and rumours, remains, beliefs, attempts, more or less showy, more or less consequential, which might show something. Show things, psscchiii, that’s how it is. The copy replaces the source. It is the proof of a vocabulary which is already the work. It’s a general construction, not of the sample, not of machinery. The copy, here, is a mixture.

Benoit didn’t wear the skin of the artificial nutcase, in the neuropath’s diary, he introduces the character, he exploits it, brings it out, not like a gimmick, but like the thing that talks. Like a thing that comes from him. The copy is used otherwise than mere reproduction. It remakes you, it’s not the same thing.

Making love to every poor daughter’s son

Isn’t it fun?

Now today, propping grace with envy

Lady Godiva peers to see if anyone’s there

And hasn’t a care.6

1“Ego devant la mort, ABJG Vs SDIP” Joe Dalton n°3 “R House”, 2006.

2Attributed to Johnny Shines in “Robert Johnson”, Samuel Charters, 1963, oak publications.

3 In law, a réfection consists in the replacement of a previous document, nul and void because of a legal technicality, by a valid document that modifies neither the nature nor the object of the agreements.

4 Bruno Munari, quoted in “Munari – Carte du Ciel”, Trinie Dalton, Partules N°27, March 2010 p.21.

5 In Two Roads Blues, words by Robert Johnson.

6 In Lady Godiva’s Operation, Velvet Underground, White Light/White Heat,1968.

articles liés

Anthropocenia

par Benedicte Ramade

Portfolio

par Geoffroy Mathieu et Bertrand Stofleth

Entretien avec Marc-Olivier Wahler

par Patrice Joly