An exploration of Cnap’s recent acquisitions

Where to see the works?

In the offices of Cnap, it is sometimes said that we are dealing with a ‘collection without walls (1). Among art institutions, this makes it a relatively unknown entity – to be honest, we know Cnap mainly for its missions to support creation, with its sessions and deadlines, placing it therefore exclusively at the level of current creation. So, to begin with, let’s recap: museums have collections – in the sense of conserving works of art – and places to exhibit them, whereas art centres are places of production.There are also the Fracs, which are funds whose purpose is to circulate their collections in the regions, primarily for educational purposes, while at the same time building up a heritage and supporting contemporary creation. Then there are institutions that are both museums and art centres (the Capc in Bordeaux) or both museums and Fracs (the Abattoirs in Toulouse). Cnap, for its part, discreetly, with its website almost as its sole showcase, is a bit of all these things at once, without being all of them.

In order to shed light on this galaxy which occupies a central place in French artistic life, and to gain a better understanding of it, this text proposes to draw on the corpus – a priori the most immediately tangible and which we imagine to still be somewhere near the meeting rooms, not yet stored in the reserves or so fresh that we only have to pull a grille or look in a half-open box to see them – of acquisitions made in 2023. More than 100 works have been chosen (to join the 107,000 or so in the collection, as we shall see later), and their variety will give us a better understanding of the intentions of Cnap when it buys from artists or their gallery owners. Let’s take a look at a few works (2) and follow their histories and destinations, before and after the acquisition committee says yes (3).

Political trajectories

Very often, it is the works themselves that draw our attention to their trajectory insofar as it is linked to a wider and more serious history. From this point of view, one series of photographs forcefully expresses its relationship with the times and is exemplary of what art’s commitment means: Gaza Walls (58.5 x 90 cm, 2001), by Taysir Batniji, made up of some sixty photographs, part of which were shown at the MAC VAL in 2021 during the monographic exhibition devoted to the artist. As a result, this is not a very recent work, nor does it comment directly on current events in Gaza. But therein lies its strength: it brings to life before our eyes the years of destruction of the Palestinian territory. As the artist explains, these photographs were taken during the second intifada, to save the messages written on the walls from oblivion, essentially wanted notices or accounts of disappearances. So the purchase of these photographs in 2023 is a powerful gesture that doubles down on the question of how the fate of Palestine is remembered. But it should perhaps be remembered here that Cnap is itself an institution with a long and politically charged relationship with history and the contemporary world, being the heir to the ‘Division des Beaux-Arts, des Sciences et des Spectacles’, created at the time of the French Revolution (4).

Antonio Negri (2019), shot in 35 mm by Marine Hugonnier in Paris, at the home of the philosopher (who died in December 2023, shortly after the film was acquired, is a portrait, a discussion, a thought in the process of being expressed, words and images in dialogue thanks to subtle editing. The film was shown in the monographic exhibition ‘Le Cinéma à l’estomac’ at the Jeu de Paume in 2022.

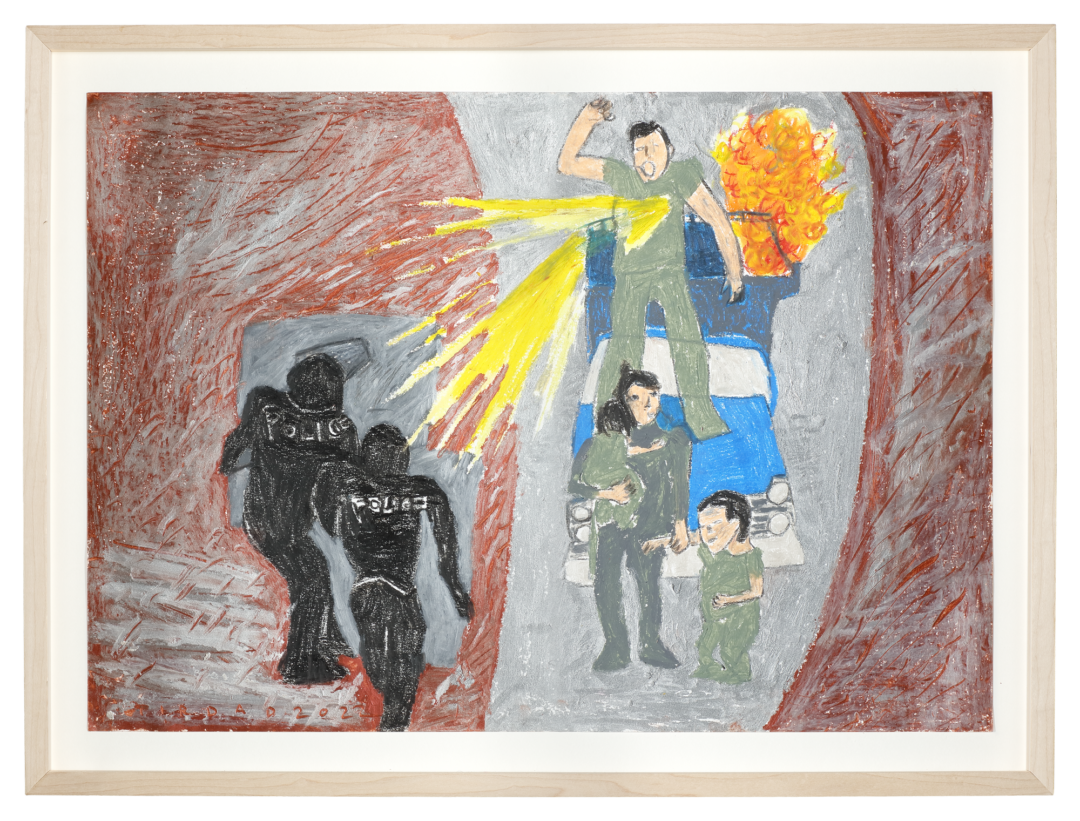

More recent works that comment more immediately on current events have also been acquired. These include a series of drawings by Tirdad Hashemi, a young artist of Iranian origin, one of which, Untitled, depicts a scene of police violence in oil pastel, paint and graphite. The word ‘police’, inscribed on oversized shields behind which helmeted figures hide, is striking; the artist has been tactful enough not to use it as the title, leaving it as an empty space. Made in reaction to the murder of Jina Mahsa Amini in September 2022 by the morality police, this drawing, like the others in the same series, transports us to Iran, but when viewed and interpreted more widely, it takes us back to France, where police violence has also caused deaths.

A photograph, at first sight rather sombre, may echo it. It is Tunnel (2017), by Julien Lombardi. It was taken in Mexico, an extremely violent country. In the foreground, we see a rock streaked with light, as if struck by lightning; a supernatural phenomenon seems to be taking place. Is it a destructive tremor? Is it the Earth’s response to human actions? Or, on the contrary, a healing light? In reality, the photograph shows a mineral extraction site, but it can also be seen as a metaphor for the current ecological and political situation, at a time when it is still possible to get out of the tunnel. ‘Where do we want to go,’ the work seems to ask, ‘into a better world, or not?

Beyond the screens

The 2023 acquisitions also include works that are intended to be presented on walls or on the floor, works that are more formally conceived but that are also inhabited by intense statements of position. Derrick Adams’ sculpture Fabrication station no 1 (2015) is a colourful, funny piece: in an imposing format (180 x 270 cm), it reproduces in fabric, vinyl and other soft materials an old-style television set, with its rounded-edge screen and its colourful pre-programme test pattern. This handmade television set makes you dream of a free, DIY, creative television channel – something that YouTube channels have all but ceased to be. In the United States, where the artist comes from, the visibility of minorities is still a battle. Adams is very active in associations and collectives working to support black artistic practices. He is represented by a French gallery, which explains why his work can be included in national collections, with the Cnap continuing the artistic tradition established at the beginning of the 20th century of a French scene made up of artists from all over the world.

This work can be compared with Plan d’évasion (vortex) from 2021, by a young artist, Lou Masduraud, who works in France and Switzerland. Modest in size (24 x 38 x 4 cm), this sculpture in brass, pearls and fabric also resembles a handmade screen, inspired by the window wells that can be seen at the bottom of houses and which are generally the only access to air and light in basement spaces. Cellars, workshops and sometimes even homes can be found behind these grilles. The title is an invitation to escape, as if from a prison, towards freedom.

La Planète close, a tapestry created in 2021 by Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, is another alternative escape, in contrast to the Internet and television. A recurring motif in the artist’s work, it is both an intellectual self-portrait and a celebration of the effect that these small, flexible, rectangular objects – books – have on us. Their cover is a promise. Once they are closed, we emerge transformed, richer and more open. Cnap has already acquired a number of works by Gonzalez-Foerster, which leads us to specify that purchases are not limited to one work per artist, nor only to young artists, as is often believed.

A real carpet, literally laid on the floor, is just as meaningful. The Mute Witness (2021), by Eva Barto and Sophie Bonnet-Pourpet, is a deliberately unattractive object that contains or reveals a secret. Here’s the secret: made by the factory that supplies the Élysée, it is largely produced at lower cost in Nepal, with finishing in the Creuse department to obtain a ‘made in France’ label and justify a high price tag. The carpet becomes the tangible proof of a front operation that hides the abuse of cheap labour and makes citizens pay a high price.

Finally, to conclude this exploration of works whose surfaces call us to see beyond themselves, we might mention the painting by Corentin Canesson, Untitled (203.2 x 198.12 cm, 2022). Composed of large swathes of colour applied with a broom, it is reminiscent of shop windows masked in Spanish white. What it shows is what it hides, in this case the emergency situation in which it was produced: just a few days before the opening of an exhibition in Austin, Texas, with his works held up at customs, the artist had to (re)produce all his works in a hurry, either by remaking them identically or, as in this case, by producing an original. As for its acquisition, it demonstrates the dynamism of painting on today’s art scene.

Healing social wounds

Until now, these works have not dealt explicitly with the body. This is not to say that the body is absent from contemporary art; on the contrary, it is very much present, but as a site of tension, stricken by conventions and obligations – in a word, biopolitics. Myriam Mihindou’s triptych Female (1999-2000), from her Sculptures de chair series – acquired by the Visual Arts Commission after the artist was awarded the Aware prize – is a powerful visual work, reminding us of our own sensations, amplified as they are. To take the photographs, Mihindou stuck needles into her fingers, as happens to seamstresses, fairy-tale princesses, people cursed by voodoo dolls, and acupuncture sessions. Carried out during a long stay in La Réunion, the gestures obey a ritual that the artist has initiated herself into. In any case, with her body, she expresses the pain that destroys or heals. A slightly different kind of intrusion is apparent in the more documentary-style photographs of young artist Nanténé Traoré. In the series Tu vas pas muter (2021-2022), he photographs the hormonal injections of people undergoing gender transition. The aim is not to glorify this moment, to make it spectacular or even to inform people who are unfamiliar with it, but quite simply to preserve traces of these decisive moments in life and intimacy. In an interview, the artist quotes Nan Goldin, indicating the way in which her images take us through a history of queer photography. The video by the duo Angélique Aubrit and Ludovic Beillard, Je veux que tu meures (2022), is very different, using fiction and the artifice of large wooden sculpted puppets to approach the representation of the body today from an opposite, slightly spectacular angle, referring to theatrical costumes and sets. Yet there is something of the order of vulnerability, of a threat hanging over a group of characters. Finally, vulnerability is at the heart of Benoît Piéron’s work and his sculpture Le Petit Prince (2022). Composed mainly of a serum holder and a uniform sewn from a green sheet, it is a direct reference to the world of hospitals and illness. Then, by means of a map centred on a location in South Kent in the UK, it pays homage to a therapeutic garden – both medicinal and aesthetic – created in the late 1980s by the English film-maker Derek Jarman, who was suffering from AIDS. The work was acquired by Cnap, and was exhibited at the Magasin in Grenoble as part of the ‘Étoiles ou tempêtes’ monographic exhibition as soon as it was purchased.

Some works in situ

The works acquired by the Cnap, which we have discussed so far, have been transferred to the reserves. There they wait to be selected, to be borrowed on a long or short term basis, placed on deposit in museums where they are made visible, or loaned for exhibitions. Fortunately, other works acquired in 2023 already have a destination. Among them, the installation by British artist Jesse Darling, Reliquary (for and after Felix Gonzalez-Torres, in loving memory), winner of the Turner Prize in 2023, conceived for the group exhibition ‘Exposé-es’ at the Palais de Tokyo, has been requested by the Capc, where it is currently on loan. For the institution that receives the work, the deposit allows it to be added to, to fill a gap or to give a new direction to its collections. Here, the work is directly in the wake of Felix Gonzalez-Torres and works on his ‘vestiges’, as the artist puts it, being made up of scraps from a curtain of pearls installed in the exhibition, burnt-out light bulbs and packaging from piles of sweets. It is a moving gesture of love towards a great figure in the history of contemporary art. The triptych, Arles – Nacht – Vincent (2015), by Sean Scully, an Irish artist based in the United States who recently fled the violence there to return to Europe, has been deposited with the Fondation Yvon Lambert in Avignon, the artist having donated the work to France. As an expression of the artist’s fascination with the landscapes of the South of France, it has been placed, as it were, in situ. But it is above all a monumental acquisition that best embodies the ideal destination for a Cnap acquisition. Sammy Baloji’s sculpture Johari Brass Band, originally created in 2020 to adorn the plinths on the façade of the Grand Palais, evokes American brass bands, but more specifically a brass band formed in the artist’s native Congo at the end of the 19th century. Given that the brass band was a reappropriation by the black American population of European instruments made of copper, which had long been mined in the Congo, Baloji’s monumental sculpture evokes a reversal of the situation through music and art. It will soon be on display at the entrance to the Cité de la Musique museum, in 2025. So at least one of the works acquired by Cnap in 2023 will be seen by a wide variety of people, whether they are attending a concert, going to a conference, or simply strolling through the park.

Let’s hope they are all taken up quickly, as works of art are made to be shown (5).

1. This is the title given by Aude Bodet, Director of the Collection Department, to her historical introduction to the catalogue La collection du Centre national des arts plastiques, published in 2023.

2. The selection is the author’s, all the works being listed on the Cnap website, in the ‘Latest Acquisitions’ section.

3. The commissions are set up for three years with, on the one hand, ex officio members who are directors and heads of institutional structures, first and foremost Béatrice Salmon, Director of Cnap since 2019, and on the other hand, leading figures from the art world ‘appointed for their expertise’. There are three of them, one for each of the ‘visual arts’, ‘photography and moving images’ and ‘decorative arts, design and crafts’ departments, and they sit from June to October. For the visual arts, the 2021-2024 commission is made up of Carole Douillard, artist, Paul Maheke, artist, Guillaume Désanges, curator, Nathalie Guiot, publisher and collector, Florence Ostende, art historian, Marie-Ann Yemsi, curator, Dorith Galuz, collector, and Cédric Fauq, curator. The ‘photography and moving images’ section includes Hannah Darabi, artist, Philippe Bazin, artist, Zeina Arida, director of the Sursock Museum in Beirut, Nathalie Gonthier, production manager at the Cité des arts de La Réunion, Christoph Wiesner, director of the Rencontres d’Arles, Audrey Illouz, art critic, Magali Nachtergael, art critic and Carles Guerra, curator. Finally, the ‘decorative arts, design and crafts’ section is represented by Constance Guisset, artist, Mathieu Peyroulet-Ghilini, designer, Gaëlle Gabillet, designer (studio GGSV), Joël Riff, exhibitions manager at the Moly-Sabata Foundation, Stanislas Colodiet, Director of the Centre international de recherche sur le verre et les arts plastiques (CIRVA), Alexandre Quoi, Scientific Director of the Musée de Saint-Étienne, Isabelle de Ponfilly, Director of Vitra, and Chantal Prod’hom, Director of the Musée de design et d’arts appliqués contemporains (MUDAC) in Lausanne.

It should be noted that in 2023, as the Cnap is moving its premises, it has replaced the transfer of acquisitions in this area with a call for applications for the ‘Create a vase’ commission, which is different in nature to acquisitions and will not be discussed in this text.

4. This makes it the oldest institution devoted to contemporary art in France, in the sense that since the end of the eighteenth century it has been acquiring works by artists of its time – and not in the sense of strictly current contemporary art. For example, its collections include nineteenth-century works purchased in the nineteenth century…

5. A website allows you to track the movement of works on loan, in France and abroad:

https://www.navigart.fr/fnac/movements/map

Head image : Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, La planète close, 2021. Tapestry, 300 x 400 cm. Courtesy Albarrán Bourdais.

Related articles

The World Through AI

by Warren Neidich

Paris noir

by Salomé Schlappi

Some white on the map

by Guillaume Gesvret