Craft is Back

Hardcore Décor: the Comeback of Craft as an Antidote to Cyberfatigue

The Post-Internet years are over, and the latest generation is acknowledging the success of neo-liberalism. By reconnecting hand and mind, craft is setting itself up as an antidote to cyberfatigue.

The troubled craftsman. A chapter so titled opens the book The Craftsman by the American sociologist Richard Sennett. Including himself in the pragmatist tradition, this former student of Hannah Arendt understands the consequences of the separation of head and hand during the evolution of Western civilization. He takes things up, so to speak, where Arendt left off. On the threshold of the 1960s, this latter made a distinction between tool and machine, turning the first term into a technical means at the service of man and the second into something external obliging the human body to adapt itself to its pace. When Sennett focuses on the situation of the world of labour at the end of the 2000s, the immaterial labour of post-capitalism had long since replaced the assembly line. If the craftsman is troubled, it is because the ethic underpinned by his discipline has been forgotten. “Technical skill has been removed from imagination, tangible reality doubted by religion, pride in one’s work treated as a luxury.”1 For Sennett, forgetting what the hand knows might well be the direct cause of the weariness of being oneself, as already diagnosed by the sociologist Alain Ehrenberg in the late 1990s. Lost in the flow, the neo-liberal individual is subject to an imperative of profitability, creativity and availability, even as the result of his labour eludes him.

The Craftsman appeared in 2008, the year of the Wall Street crash. In New York, the shock wave did not spare the creative industries. Among designers, fashion designers, artists and admen, now all at a loose end, a series of emails started to circulate. Two years later, it acquired a more tangible character by giving birth to the DIS Magazine platform. And the rest is history. By way of this rallying point was invented what might be more akin to a contemporary art movement: the Post-Internet phenomenon. Ten years later, this collective adventure is coming to an end. Two years ago, the 9th Berlin Biennial curated by the DIS collective fiercely resembled an early retrospective show, while the end of DIS Magazine’s activities this winter confirmed that that adventure would belong to history. In the shadow cast by it, artists who were affiliated with it are now each honing and specifying their solo careers. This is how things currently stand. So it is from the time-frame of this position, the one we are presently in, that we come back to the troubled craftsman, while the anxieties of the late 1990s are quietly coming back to the fore. In the present-day art world, the great comeback of the politics of identity and engaged art, focusing on “subverting” and “questioning” the hegemonies of race, gender (above all) and class (at times) is being more clearly identified. But craftsmanship, understood in the broad sense as a framework of thought, not to say as a practice of resistance, is also part and parcel of this, as is illustrated by the first portents which are seeing young artists putting traditional and even marginal techniques back at the centre of the artistic ecosystem.

Post-Internet and neo-Luddites

Renaud Jerez, View of the exhibition Miroir noir, Les Abattoirs musée – Frac Occitanie Toulouse © R. Jerez ; Photo : Sylvie Leonard.

Renaud Jerez, View of the exhibition Miroir noir, Les Abattoirs musée – Frac Occitanie Toulouse © R. Jerez ; Photo : Sylvie Leonard.

This switch of paradigm is attested to by two major events. This Spring saw the opening in New York of the latest New Museum Triennial, one of the best occasions for putting a finger on the trends exercising young artists the world over. We can still remember the previous Triennial, “Surround Audience”, curated in 2015 by Lauren Cornell and the artist Ryan Trecartin, an anthem to augmented subjectivities and empowerment by hybridization which brought together artists and collectives such as DIS, Aleksandra Domanović, Josh Kline, Oliver Laric and Avery K. Singer; it was extended by advertising campaigns signed K-HOLE and a web series piloted by Casey Jane Ellison, and was imprinted in our cortexes by the image of a triumphant Juliana Huxtable posing as an at once post-human and post-gender cyber-goddess. With “Songs for Sabotage” we change planets. Back to Earth, for a journey to the centre of the darker human impulses involving domination and oppression. For Alex Gartenfeld and Gary Carrion-Murayari, the “sabotage” in question must undermine the foundations of west- and white-dominated propaganda in which artistic infrastructures take part. The reproach about distributing artistic innovation along a New York-Berlin axis, which could be levelled at the last Triennial, is no longer valid this year. On the contrary, many of the works selected seem above all to have been chosen because they hail from a geographical region where neo-liberalism has more or less got a foothold, expressing through exhibitions the dream of a garden of Eden with a surprising primitive quality, to say the least. So there has been a major comeback of media such as figurative painting, but also, and above all, tapestry (with Zhenya Machneva), ceramics (Daniela Ortiz) and wood sculpture (Claudia Martínez Garay). Enough to cause Peter Schjeldahl, the New Yorker art critic, to observe that “handwork seems back in, for one striking thing, and innovation seems out”.2

With the 10th Berlin Biennial to come, the same shift seems to be being reproduced: this year it is titled “We Don’t Need Another Hero”, referring to the song sung by Tina Turner on the original sound track of the film Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome in 1985. What can the Mad Max franchises, chaotic dystopias set in a context of all-out war and natural resource shortages, have to say about our day and age? In their statement of intent, the curators—Gabi Ngobo assisted by Nomaduma Rosa Masilela, Serubiri Moses, Thiago de Paula Souza and Yvette Mutumba—referred to the backdrop being the present-day “collective psychosis”.3 So the 10th Berlin Biennial does not “provide a coherent reading of histories or the present of any kind”, but on the contrary “explores the political potential of the act of self-preservation”.4 This return to self, to the private and community sphere, thus points to a return to ‘care’, understood in its accepted restrictive sense. The invention of ways of existence is replaced by “preservation” in the face of contemporary subjectivities which, by dint of being entangled in the nets of technological totalitarianism, have become “toxic”—the words are again taken from the Biennial curators’ statement of intent.

The concrete utopia of craft

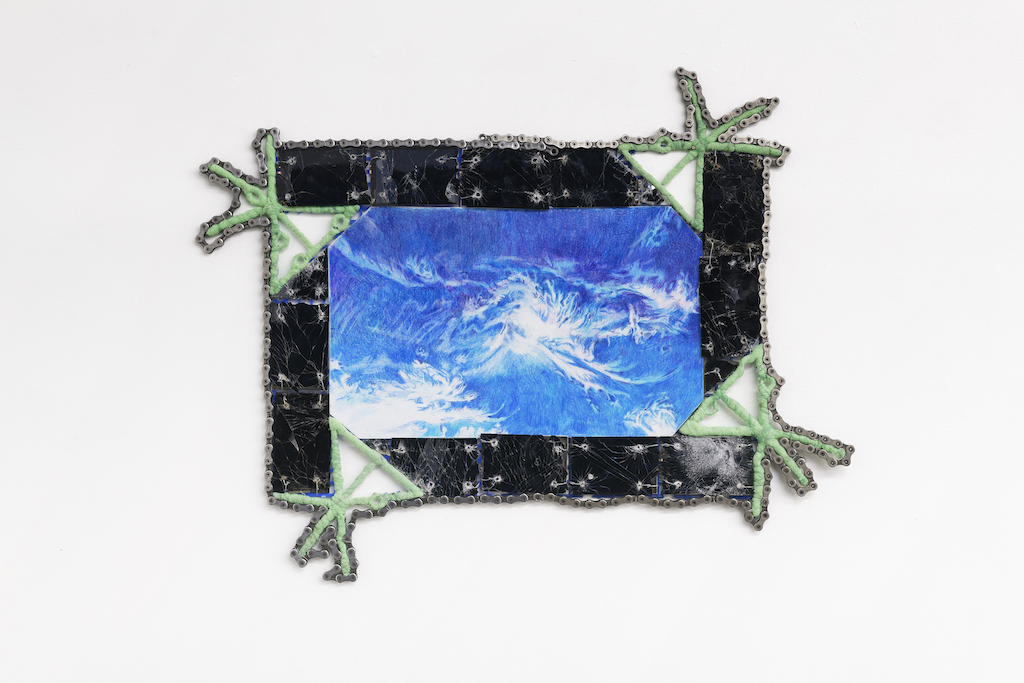

Anna Solal, AFTERNOON CLOUDS. Broken smartphone screens, bike chains, ropes, tulle, metal thread, colored pencil on paper, plexiglas, 64 × 50 × 1 cm. Courtesy New Galerie, Paris.

Without any higher authority, and making use of a tacit knowledge learned by trial, error and repetition, craft appears to be a refuge value. The model of this type of knowledge, which resounds with an infatuation with the feminist methodology of care and ‘situated knowledge’, does not so much draw from history as from an expanded geography of art, where we presuppose a flowering of alternatives to a Western system of contemporary art which, for its part, is irreversibly contaminated. The fact is that the phenomenon of this return to craft was already being sensed among many young artists who previously appropriated connected, accelerated and de-materialized life. In his show at Les Abattoirs in Toulouse, Renaud Jerez re-incorporated his mechanical dolls, like a post-human Hans Bellmer, in a household environment: lights cobbled together from Venetian masks and baroque pompons; benches covered with patchwork blankets surmounted by Tibetan turrets. Forms coming into being from manipulation and not planning, with the artist pointing out that he is not capable of drawing them before letting them spread during the act of their making.

With Anna Solal, the art of assemblage also presides over the birth of extremely detailed and painstaking compositions. Early in 2018, the New Galerie, epicentre of the introduction of Post-Internet artists in France, held a solo show of her work. In it, people discovered her marquetry works made by putting broken smartphone screens together, end to end and held in place without any glue, along with bicycle chains, hair slides and a host of other trifles made of plastic, scrap metal and any other kind of recycled material. If Richard Sennett extends his definition of craft to Linux exploitation systems,5 he installs the hand’s thinking actually within computer matrices. “Skill is a trained practice; modern technology is abused when it deprives its users precisely of that repetitive, concrete, hands-on training”,6 to borrow his own words. In Berlin this time, in late May at the Neu Gallery, Yngve Holen inaugurated an exhibition presenting the latest developments in his work, reproducing in sculpted wood the hubcaps of cars for which he was hitherto known. Without having himself had recourse to that “hand training”, the simple aesthetic conveyed the evolution of mentalities from a technological fetishism to a neo-bricolage. It is thus impossible not to think of the opening lines of Richard Sennett’s book describing the experience of looking through a window at a carpenter’s workshop: the order reigning therein, the smell of freshly sawn wood, the precision with which are inlaid the pieces of the marquetry he is at work on. An idyll as much as a concrete utopia, hewn like a tunnel in the heart of globalized neo-liberalism.

1 Richard Sennett, The Craftsman, Yale University Press, 2008, p. 21.

2 Peter Schjeldahl, “Aesthetics and Politics at the New Museum’s Triennial”, The New Yorker, 5 March 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/03/05/aesthetics-and-politics-at-the-new-museums-triennial

3 http://www.berlinbiennale.de/about

4 Ibid, “The 10th Berlin Biennale does not provide a coherent reading of histories or the present of any kind. Like the song, it rejects the desire for a savior. Instead, it explores the political potential of the act of self-preservation”.

5 Richard Sennett, op. cit., p. 51: “The smart machine can separate human mental understanding from repetitive, instructive, hands-on learning. When this occurs, conceptual human powers suffer”.

6 Richard Sennett, Op. Cit., p. 52.

(Image on top: Yngve Holen, Rose Painting, 2018. Installation view, Galerie Neu. © Y. Holen. Courtesy Galerie Neu, Berlin.)

- From the issue: 86

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Drifting all dressed up: portrait of the artist as a nomad, Art & Cultural Appropriation, TV Resists,

Related articles

Some white on the map

by Guillaume Gesvret

Toucher l’insensé

by Juliette Belleret

An exploration of Cnap’s recent acquisitions

by Vanessa Morisset