Curator’s marathon : Frac Sud, Mucem, Mac Marseille

Being as consumed as possible within your individual limits is the fundamental principle of running, and it’s also a metaphor for life – and, for me, a metaphor for writing. I think many runners would agree with that definition.

Haruki Murakami, Self-portrait of the author as a long-distance runner

For the writer, no other subject is as intensely personal as boxing. To write about boxing is to write about oneself – however elliptically and unintentionally. To write about boxing is also to be forced to reflect, not just on boxing, but above all on the limits of civilisation – on what being ‘human’ means or should mean.

Joyce Carol Oates, On Boxing

2024, the year of the Olympics… it’s hard to escape the media maelstrom that is invading the airwaves and screens, sparking as many critical debates about the demands made by employees who, for once, are in a position of strength, as it does considerations about the ability of the “ville lumière” to make the many long-awaited trans-regional connections and ensure the safety of the crowds of panicked visitors. Far from the organisational headache of the world’s biggest event in terms of audience numbers, the artistic events on offer at the Paris Olympic Games are an opportunity to revisit the long-standing relationship between art and sport: While sport has attracted a great deal of attention from artists (particularly painters) since the early days of the Olympics, it is only more recently that sport has become a major source of inspiration for many contemporary artists, who have engaged in profound reflections on an essential dimension of human activity, which they are able to sublimate, transcend, divert at will and, of course, criticise through the whole range of their practices. In Marseilles, the three main venues for contemporary art – the Frac Sud, the Mucem and the Musée d’Art Contemporain – have come together to create an event of varying degrees of sensitivity, under the leadership of Jean-Marc Huitorel, general curator of this tripartite event, an eminent connoisseur of the game and a true marathon runner in the field.

As the same Huitorel writes in the preamble to the catalogue Des exploits, des chefs-d’œuvre, the question of sport in art goes much further than a banal theme that should be treated like any other opportunistic subject, because, according to him: “Art takes sport into account because it occupies a considerable area of contemporary reality. Sport says as much, and probably more, about art than art says about sport”. Moreover, while he tries to find similarities between the two activities, he is careful not to compare them: “art is not sport and sport is not art”, he declares a little further on. While he is also careful not to make hasty comparisons with the original Olympic Games, those of ancient Greece, which were part of a societal continuum in which the exaltation of the warrior merged with that of the athlete, the reference to calcio fiorentina seems more relevant because it refers to a dimension already present in antiquity, that of the game (rather than sport), and which can be seen as heralding the whole festive and celebratory apparatus that accompanies our modern Olympic Games. Jean-Marc Huitorel goes on to demonstrate the crossover between art and sport (the term first appeared in the nineteenth century), foreshadowing the increasingly close interweaving between the realm of pure competition and that of its representations and other instrumentalisations. It was nothing less than modernity taking hold of sport and all that it offered in terms of inspiration to artists of all disciplines, but also of course to photographers and other film-makers for whom sport was an infinite repertoire for capturing movement, not to say an acceleration of things that was already well underway at the beginning of the 20th century. But it was not until the end of the century that artists’ treatment of sport reached a truly reflexive maturity and, like other areas of human activity such as business, acted as a veritable representational engine, with all that this implies in terms of anthropological and societal considerations, more or less consciously on the part of their authors.

Tableaux d’une exposition au Mac Marseille

It was in Marseilles that the Olympic flame took off on 9 May, entrusted to Florent Manaudou, a fact that was hard to ignore in such an undertaking, which is as much a matter of nationalist chest-thumping as of the spirit of Coubertin, to whom the organisation of the Games refers. It was only logical that the City of Marseille should make a similar show of strength in (contemporary) art, even if we are entitled to wonder how much of the promotional mass that the Olympic Games have become over the years is attributed to the media coverage of these exhibitions. The most notable achievement of this trilogy certainly goes to the curator of these exhibitions, who has succeeded in bringing together three venues with very different vocations in terms of art in Marseille: the Frac Sud, the Musée d’Art Contemporain and the Mucem.

Laurent Perbos, Invert Pyramid #2, 2022. Footballs, aluminium frame, sheathed wires. Conseil départemental des Bouches-du-Rhône, Marseille, France. Camille Holtz, Série « Tennis Forever », 2023. Balle signée. Diana et Gaia. Gloriana. Isabella. Juliette. Lucie.

Sac avec signatures. Trois Copines (Mariam, Jermine et Jana). Trophée. Prints on Canson paper, collage on dibond. Production Frac Sud – Cité de l’art contemporain, Marseille, France. Courtesy of the artist.

Trophies are precisely what the Mucem is all about, and it has placed its part of the exhibition under the aegis of those objects that come to symbolise the victory of sportsmen and women, sealing it in more or less precious metals. For artists of all stripes, this production is an absolute godsend, offering them an incomparable opportunity for playful diversions and other excesses. More to the point, the exhibition, curated by Jean-Marc Huitorel, is not just a display of trophies that could be summed up as banal cups and medals whose design has not always demonstrated enormous formal inventiveness. Entitled “Trophies and relics”, the first section is more concerned with the diversion of accessories essential to the practice of a particular sport, the tennis ball or the pétanque ball, with the round ball remaining the great favourite of artists who have taken great pleasure in diverting its form. While Fabrice Hyber turns it into an impractical cubic object, Laurent Perbos stretches it out like a giant capsule, and Yoan Sorin peels off its leather casing to make astonishing bouquets of flowers, an iconoclasm that has more to do with poetic gestures than outright irreverence. Johanna Cartier manages to worm her way into this still very masculine history of the round ball by pimping it up with a host of rubies, sapphires and other cheap pearls… The presentation in the form of a museum showcase accentuates the reliquary effect: it was difficult, within such a sub-theme, to allow great plastic gestures to express themselves, as is the case at the Frac or the museum; a trophy inevitably means reducing the artistic gesture to the scale of the latter. But the curator’s intention was also to create a relationship, if not a tension, between the media treatment of the feat and its artistic resolution, namely the trophy. All the front pages of L’Équipe, a medium that it would have seemed unseemly not to include in an exhibition of this kind, bear witness to the real popular fervour that this staple of the daily press both records and sustains. The critical and gestural deployment on a larger scale is not entirely absent from an exhibition that gives pride of place to artistic dribbling, but also to the celebratory dimension: the installation by Ferruel & Guédon, as well as revealing an unexpected fan attitude on the part of the duo, reinforces the feeling expressed above of the incomparable potential of sport to produce completely new repertoires of forms. Jeremy John Kaplan’s suspension, for its part, takes up the incomparable challenge of verticalizing a practice that is absolutely horizontal, that of pétanque, while at the same time paying tribute to a discipline that is eminently Marseilles-based. The same goes for Neal Beggs’ brilliant video Expressway, which stages a fictional competition between the (lateral) climbing of a cautiously slow mountaineer and the flow of cars on the motorway going in the opposite direction. An almost metaphysical reflection on the beauty of gratuitous effort by a climbing enthusiast seemingly oblivious to the mad acceleration of human activity. Marseillaise artist Fatima Mazmouz’s beautiful installation (Que reste-t-il de nos amours?) introduces a bit of critical distancing by showing the pitfalls of practising a beloved sport when you find yourself in the clutches of ordinary racism in 1960s France.

Jeremy John Kaplan, Crossings (Intersection en suspension), 2017. Metal, wood, magnets, fishing line. Courtesy of the artist.

The Musée d’Art Contemporain recently reopened its doors, after a welcome reconfiguration that saw it gain new spaces previously dedicated to the museum’s reserves. Its new director, Stéphanie Ayrault, generously welcomed Jean-Marc Huitorel’s proposal, allowing him to take over the MAC’s first three galleries, as well as its newly recovered storerooms. Unlike the exhibition at the Mucem, which focuses on small-scale works, here at the museum, the spaces and picture rails allow for large lateral ensembles and voluminous displays: Julien Beneyton’s work, for example, dedicated to boxer Jean-Marc Mormeck, takes up a large part of the new spaces. A total work, combining drawing, painting, video and sculpture, L’Œil du tigre is a powerful tribute to a shock sportsman, a portrait of this latest giant of French boxing from every angle and with every injury; it also makes us reflect on the fascination that many artists feel towards the ‘noble art’, which could perhaps be explained by a desire to stick as close as possible to reality by moving away from the aporias of representation. “Tableaux d’une exposition”, as its name suggests, expresses his love of painting in all its forms, in the sense of the tableau format, as Jean-François Chevrier put it. In fact, the MAC’s exhibition catalogues all the aspects mentioned above, everything that sport does for art, and how artists draw on this incomparable register to draw inspiration from it and integrate it into their visual universe. From abstract motifs (Raoul De Keyser, Frédéric Lefever) to portrait series (Pierre Gonnord), from caricature (Guillaume Pinard) to allegory (Jean Bedez), from feminist and committed painting (Johanna Cartier, Noel W. Anderson) to the attempt to exhaust points of view (Guillaume Bresson), from basketball (Antonio Recalcati, Noel W. Anderson), shot-putting (Jérémie Setton), athletics (Christian Babou), Basque pelota (Frédéric Lefever), derision (Alain Séchas), hagiography (Julien Beneyton), synecdoche (Christian Babou), oxymoron (Jef Geys), there is a clear desire to list all the ways in which artists look at sport, perhaps the effect of cataloguing is a little too pronounced, and there is a lack of rupture in the way the works are exhibited, more wisely juxtaposed than intermingled, more “individual swimming lane” than “rugby scrum”, even though, to the credit of the curators, the museum’s layout in bays makes it difficult for the works to interpenetrate and engage in dialogue with each other.

In center : Gethan & Myles, Icare / Mont, Ventoux 80 km/h, 2017. Mixed media. At the back : Lieven de Boeck, The World Unmade #5, 2015. Paint, 40 basketballs. Courtesy of the artist and Meessen De Clercq, Bruxelles.

The Frac Sud, for its part, opened all its spaces, including the project room and the documentation centre, to the exhibition entitled “L’Heure de gloire”, again curated by Jean-Marc Huitorel, but with the complicity of its director Muriel Enjalran, who initiated the Marseilles project. The exhibition takes up the same issues as the Mac, but occupies a more ‘uneven’ space than the museum, and takes a more ‘deconstructed’ approach, giving pride of place to artists who do not fit neatly into the image of the sportsman or sportswoman, These include Louka Anargyros’s floor sculptures, which deal head-on with the issue of homophobia in sport; Estelle Hanania’s series of photos of the wrestler Cassandro el Exótico, who openly displays his gay orientation in what is presumably a very unwelcoming environment; and Noel W. Anderson’s wall hangings, which make reference to the gay and lesbian image of the sportsman or woman. Anderson’s wall hangings, which refer to the situation of black sportsmen and women, whose omnipresence on basketball courts in the United States and elsewhere does not seem to be bringing about any major changes in the situation of racialised people… Alongside the question of the representation of women, raised again in a more than allusive way by the work of Johanna Cartier, or by that of Lea Guldditte Hesterlund’s Discobolus, which confronts the canons of beauty in sculpture, these themes are more than present in the exhibition, without it becoming a platform for the defence of minorities: many of the works have an absurd, zany dimension, such as that by the Japanese artist Taro Izumi, who reproduces in sculpture the figure of the ‘football backflip’, allowing the viewer to potentially adopt the acrobatic position of a footballer. Then there’s Thomas Wattebled’s unclassifiable work, which explores all the possible ways of using the famous podium, which has become the real hero of these Olympics, instead of the medallists; not forgetting Delphine Reist and her strange grouping of tricoloured sports bags animated by almost indistinguishable movements. Gilles Mahé joue au golf en pensant à Rudy Ricciotti (1993-1996) is an emblematic work by the artist from Saint-Malo, part of a series of exchanges with his collector that go well beyond the production of a banal artefact to express the intensity of the bonds of friendship and intelligence that can exist between the two protagonists. It’s a humorous work that resonates perfectly with the reflective framework of the exhibition.

Color video, 9 min. RING III, 2001-15. Ring corners, ropes. Courtesy of the artist.

And there’s always boxing: two works in the exhibition are dedicated to this fighting sport, which is a firm favourite with artists. The first is a video by the artist Zuzanna Janin, who is engaged in a seemingly unequal combat with a famous boxer from her country, a veritable icon, who ‘dominates’ her with his tall stature and broad shoulders. Here, the fight evolves from roughness to closeness, becoming more and more like a game between two dancers who observe and befriend each other, like a metaphor for love relationships. And once again Yoan Sorin beckons us from a plaster punching bag – methodically destroyed by his own hands equipped with brass knuckles – with only traces of the ‘fight’ remaining. Why is boxing so prominent? Certainly because it’s the sport that harbours the most violence, tension, apprehension and physical commitment, to the extreme, but which also allows us, as in Sorin’s performance, to express buried emotions and family histories in a liberating catharsis(1).

1 The artist is the grandson of François Pavilla, the first boxer from Martinique to become champion of France.

Mixed media : double video projection. Courtesy of the artist and galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois, Paris, France.

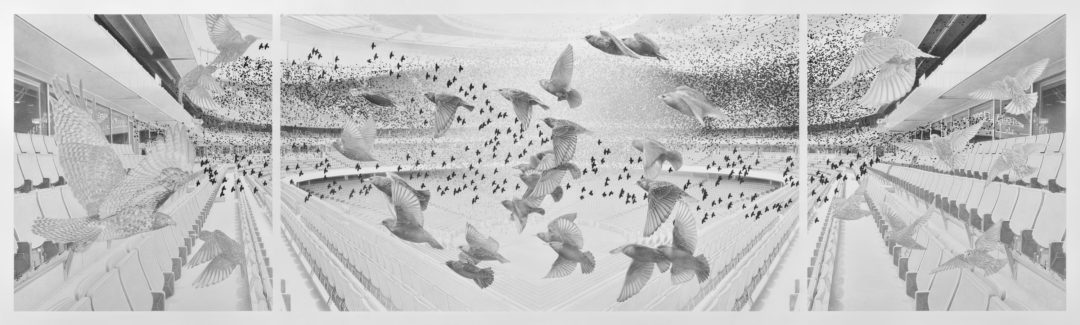

Head image : Johanna Cartier, ce n’est pas forcément un but en soie, 2022.

Football goal, polyester voile, rhinestones, artificial turf, jerrycans, adhesive, baby bottle nipple. Courtesy of the artist.

- From the issue: 108

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Where have all those reviews gone?, Are We All Migrants?,

Related articles

The World Through AI

by Warren Neidich

Paris noir

by Salomé Schlappi

Some white on the map

by Guillaume Gesvret