Some white on the map

The title of last year’s Venice Biennale, ‘Strangers Everywhere’, called for a literal reading. The Danish pavilion, crossed out by its Greenlandic name, indicated the way out and a more general reflection on the strangeness of the contemporary body. In the work of Pia Arke, Inuuteq Storch and Bouchra Khalili, the body is rendered alien to a landscape emptied of colonial picturesqueness, or reluctantly reduced to a map of the world drawn by others. These three artists erase the body from landscapes, even if it means doubling the spectral white or, on the contrary, tearing it apart to reincarnate the absent figures. A simple line also draws a path of pain suspended in the lead of a felt-tip pen.

White on the map

Anyone who has been to Uummannaq always ends up going back, because somewhere on the little island of cliffs, he lost his heart.

Greenlandic song

When we find our bearings on a map or in an exhibition, it’s not always easy to find our way back to external reality. There’s always the risk of misjudging distances, misidentifying places, losing sight of the relationship (of scale) between what was clearly delineated (a place, a theme) and our experience of reality, full of irregular reliefs in which to get lost. Does an exhibition still help us to read, in other words, to find our bearings in the unpredictable?

Calm scar

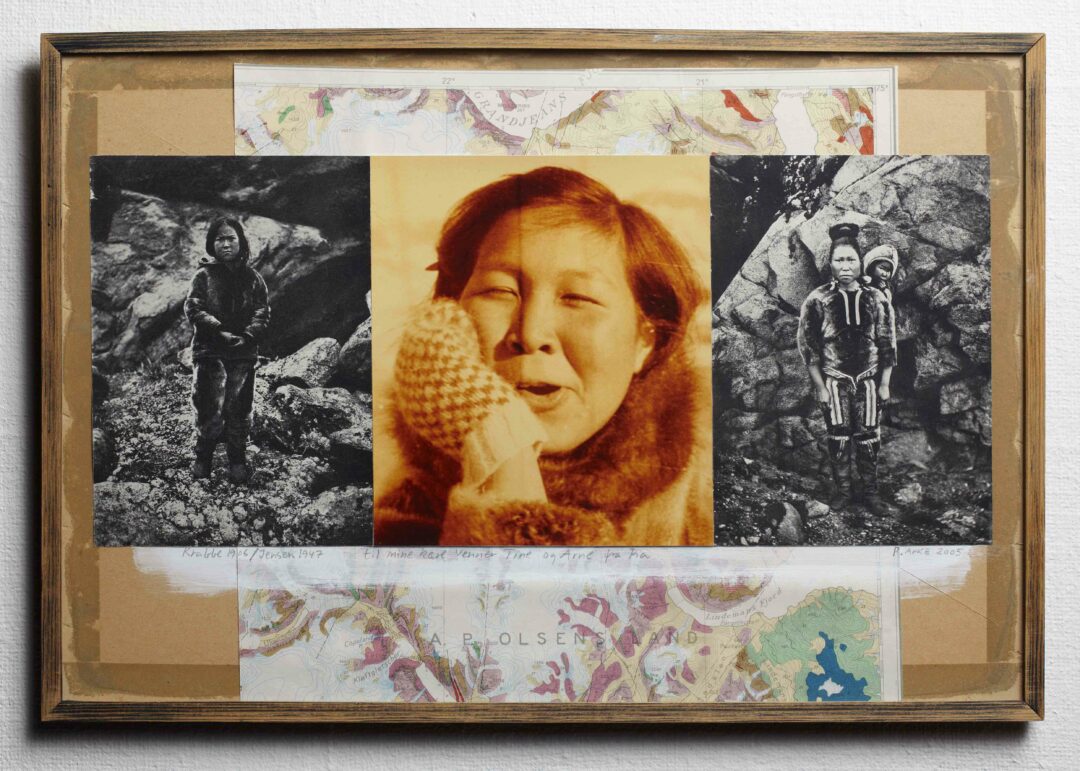

A body plunges into a landscape that it ends up tearing apart at the risk of tearing itself apart; it undergoes the landscape as much as it works it, crumpling it up, drawing other broken, indented lines. In the filmed performance Arctic Hysteria (1996), Pia Arke (1958-2007) swims naked in the middle of a large photograph of an Arctic landscape captured by a camera obscura of her own making, a small white cell on a human scale that can be moved, for example, to the edge of a cliff in Greenland. The artist was born to a Greenlandic mother (a more appropriate term than ‘Inuit’) and a Danish father. Her works evoke this family split, shrouded in a constant silence: a continual and conflicting issue in her performances, photographs and montages – no ‘stable belonging’, according to her – which brings this series to a close. Here, an artist, there, a coldly distanced ethnographer, we don’t know whether the neutrality of her face (in some of the photographs) bears the unspeakable violence that can’t find its way anywhere other than on the ridge or escarpment, on the cliff, on the recently detached iceberg, or on her own body, scarred by the removal of a breast.

In a filmed interview, Pia Arke talks about a white hut that can be visited in the exhibition, which reminds her as much of the huts of Greenlandic fishermen as of the small houses of European tourists – kitschy ersatz of the former. In another series of photographs, she appears among the Three Graces, this time dressed and with no other reference to the classical European motif than their frontal position, standing and facing backwards; these three women are each holding a Greenlandic ritual object. Emotion, almost absent, flees from Western references, the better to parody and criticise them. If the hysterical crisis ironically lends its title to the video performance and the exhibition (Arctic Hysteria), it is an echo of the Western imagination which, before Freud, identified the gestures of indigenous rituals as irrational and incomprehensible. For the exhibition, the large-format photograph torn during the performance has been patiently glued back together, in an ambiguous tension between tearing and healing – of the image, of colonial history and of the artist’s own body, all of which are profoundly linked.

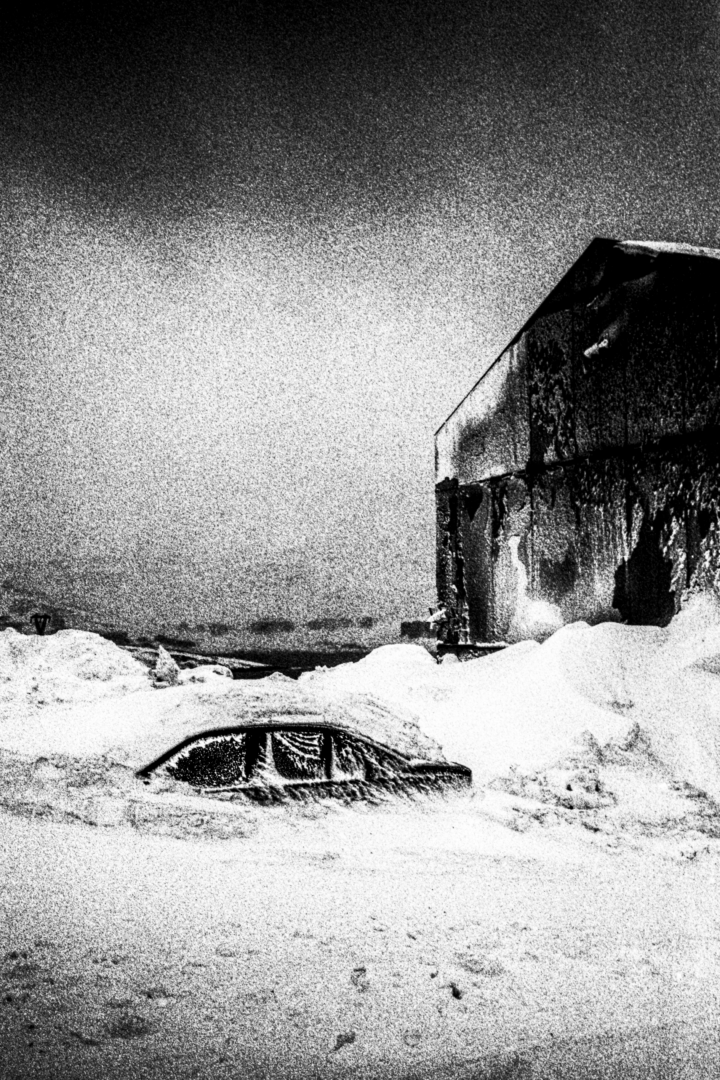

At the KW in Berlin, the artist’s first solo exhibition in a non-Nordic country, these few images of the Greenland coast are striking in their intensity of contrast, worthy of the craftsmanship of Nicéphore Niépce: is the snow white or black? Not to mention a summer without night and a winter without day – we’re already starting to forget that, but not the overexposed, hyper-contrasted void. The opposition of black and white can do nothing about it (one does not fill the other). There is no remedy for the emptiness that the artist seeks to dispel by plunging into photography, and before that into the camera obscura; entering this void, or one’s own skull, damages the body to some extent, whatever the surrounding exterior (museum or world). Is it to return ‘fortified by an irrecusable negative’ (Beckett)? Or fortified by the negativity of an early decolonial critique of such a romantic cliché, which Pia Arke was already talking about in her thesis ‘Ethno-Aesthetics/Etno’stetik’? It’s a classic depiction of the Far North, emptied of its thousands of inhabitants, and so it’s a question of inhabiting it in spite of everything – fighting with your body against the emptiness in the image.

Another exhibition, this time in the Danish pavilion in Venice, gives us a better understanding of the Berlin exhibition: Inuuteq Storch’s ‘Rise of the Sunken Sun’. As if in the middle of a navigation, with all geolocation out of order, a new landmark (an object visible on the horizon) helps to clarify a shifting and uncertain position on the map. As soon as you enter, Denmark is crossed by the word ‘Greenland’ in the Greenlandic language, Kalaallit Nunaat (Land of Humans). Inuuteq Storch’s intimate or more mysterious snapshots stand in stark contrast to the images created by the first Danish colonial expeditions. From 1721, for primarily economic and religious reasons, this colonisation – supposedly without direct oppression – was not without consequences, notably on the nomadic lifestyles of the populations, who became sedentary in order to be controlled. The immense whiteness on which to project dreams of adventure, like the perfectly blank page of a script to come, a terra incognita that covers the image of another, deleterious whiteness, the one dug into memories by the colonial process by dint of erasures, both real and symbolic. Crossing out Denmark may not be enough to recover the lost name: this ‘invasive white’ that obliterates memories, to use Karima Lazali’s expression in the specific context of post-colonial Algeria1, sometimes survives even in the silence that follows independence, or in this case relative autonomy. A blank space filled with idealisations that prevent any healing or words from being spoken.

In her montages, Pia Arke oscillates between the staged picturesque (Wonderland) and the quest for an elusive archive, both personal and collective. There is no avoiding the danger: by neutralising all speech, the silence imposed can freeze subsequent generations in a wordless haunting. It can also force us to retrace the threads of violence that have been knotted and woven together, such as the forced displacements (of Pia Arke’s grandparents in the 1920s) and other post-colonial sufferings, of which the many suicides are still the result today. To say, to show, or at least to mark out this silence – her camera obscura being a beacon like any other, capturing not so much the landscape as the possibility of beckoning back to it (Untitled [ Nuugaarsuk, with footprints]), including for the viewer.

Pia Arke’s work allows itself to be overwhelmed by our contemporary gaze. On a map, the variability of the thickness of the ice cap as a function of the seasons is represented on the edge of Greenland by diluted white, revealing the earth through transparency: a micro-detail on the edge of a map, a ready-made with no aesthetic intention, which we should nevertheless pay attention to, even though the theme of the ecological threat probably did not exist with the same gravity at the of the artist in activity and of most of the works or elements exhibited, including the map (the 1980s). Since then, melting ice has caused landslides and deadly tidal waves that bear no comparison with the period before 2000. Today, this melting is definitely underway, and it’s more than ambivalent: metaphorically, it’s bringing back memories that should have been frozen until now, but because of it, huge blocks of ice and stone are also collapsing. A contradictory melting pot, between emergence and tragedy, whose contradiction must continue to be expressed; for example, with the tranquil photographs of Danish settlers from the singular point of view of a Greenlandic photographer (Mirrored by Inuuteq Storch), while the removal of white in another series (Necromancer) still allows us to see… white, confirmed instead of evacuated, pushed to its point of haunting, disturbing irradiation.

One idea comes to mind: behind the pervasiveness of the themes in these two exhibitions (colonisation, feminism), an open-ended series would suggest ricochets that are otherwise unpredictable, no longer from theme to theme, but from term to term, each unstable, maintaining infinitely variable relationships (from the body to its history, from history to geography, from geography to the changing climatic era, or from recent technologies to non-Western mythologies2, from the uncertain present to developments that are impossible to predict). In a constant variation of scales, both temporal and spatial, where the world and the map affect each other.

Pavilion, La Biennale di Venezia. Photo : Ugo Carmeni.

Erasures

We keep reading around the edges, wandering and making mistakes. Nothing is ever certain – there are no other ways of reading or of creating margins. Where to make what resonate?

For reasons not communicated by Google, the digital map of Gaza, on Google Maps and Waze, has become partly white, emptied of information, such as real-time traffic; to prevent troop movements from being read on it, according to an express request from the Israeli army, but also and no doubt out of political and legal disempowerment3. As a result, there has been no route or commentary since then. The white areas on the map, hitherto reserved for terra incognita (from the point of view of the explorers-colonisers), here indicate areas of destruction that have been rendered mute and invisible. There was a rumour that Google had removed Palestine from the map. In fact, it had never appeared on the map other than surrounded by dotted lines. In Ukraine, public places and even the terrain had already disappeared from Google Maps at the start of the Russian invasion, to avoid making them targets, according to interpretations that again cannot be verified.

On eight screens set up in the Arsenale at the Venice Biennale 2024, Bouchra Khalili has projected eight videos, each featuring the hand of a migrant drawing on a map the different routes he or she has taken in exile, which he or she comments on simultaneously, off-camera (The Mapping Journey Project, 2008-2011). In one of the videos, the felt-tip pen no longer works during a journey between Libya and Algeria. The playback comes to a halt again, on an almost nothing that no label will mention. But it’s important, and the memory of that blank persists. The hand resumes and the path reappears in a rapid repentance. This invisible trace, for a time only, is the absent commentary on the map, whose functions have been suspended (of control, recognition, legal and political definition). An invisible form, the silence of the trace that continues to pierce the testimony. In Bouchra Khalili’s installation, each pause in the spoken word sometimes implies an imprisonment of several months. In their suspension, words and gestures deal with the impossibility of saying and showing, punctuating the voids that ultimately give their fragile syntax to sentences that are perhaps unaddressable in any other way.

A common silence for examples without common measure.

In the blank of the cards, oblivion is distilled little by little, wrapping itself up to play, to provoke itself, in a harmless representation of the world (a photograph, a map), but also to act, all at once, as a catalyst of memory, even in spite of itself: this tear, I remember now, is lodged in its voice.

You can tear up a map in a rage, because you’re looking in vain for what’s no longer there. Or you can observe its ongoing transformation, understand what moves it in spite of itself and expresses itself in silence, far from it, in the austere maturation of a search as long as life, or in a cry that will never finish resounding.

Courtesy of the artist © Inuuteq Storch.

Courtesy of the artist © Inuuteq Storch.

Courtesy of the artist © Inuuteq Storch.

Courtesy of the artist © Inuuteq Storch.

- Karima Lazali, Le trauma colonial. Une enquête sur les effets psychiques et politiques contemporains de l’oppression coloniale en Algérie, Paris, La Découverte, 2018.

- For another example of variation in scale, between the present of technology and non-Western mythologies, see CRO: Félicien Grand d’Esnon and Alexis Loisel-Montambaux, ‘La vague techno-vernaculaire’, in Zérodeux # 105 : https://www.zerodeux.fr/essais/daniel-pommereulle-et-mathis-altmann-a-pasquart-2/

- See Bloomberg, 23 October 2023: https: //www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-10-23/google-disables-live-traffic-in-israel-gaza-at-military-request

Head image : Bouchra Khalili, The Constellations series, 2011. 8 sérigraphies sur papier / 8 silkscreen prints on paper, 60 × 40 cm chacune / each.

The Mapping Journey Project, 2008-2011. Installation vidéo, 8 vidéos monocanal, couleur, son. Dimensions variables / Video installation, 8 single-channel videos, color, sound. Variable dimensions. Sea-Drift, 2024. Broderie sur lin naturel teint à l’indigo / Embroidery on natural indigo-dyed linen, 470 × 170 cm. 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere. Photo : MZO: Marco Zorzanello. Courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia and the artist.

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Matter in Suspense, New Enumerations, Describe, Lighten,

Related articles

Toucher l’insensé

by Juliette Belleret

An exploration of Cnap’s recent acquisitions

by Vanessa Morisset

Curator’s marathon : Frac Sud, Mucem, Mac Marseille

by Patrice Joly