The Polyphonic History of Net Art, An Eternal Network?

“In our present era there can be no art that is not somehow connected to or reliant upon the Internet” writes Melanie Bühler in her introduction to No Internet, No Art,2 thus implyingthat even non-digital art per se—that is to say art not employing digital technologies as its “primary medium”, to follow her wording3—has recourse to the global network in a way or another. Would all art have become net art?

When the Canadian artist and writer Douglas Coupland famously said a few years ago: “I miss my pre-Internet brain”,4 it was surely true by then. But today? Would he still be able to precisely remember what his pre-Internet brain was?5

Interestingly enough, the youngest generation of artists to come up on the art scene today brings together people born in the nineties, that is to say too young to have a memory of this kind. As we know, the Internet became the official name of the existing computer networks in 1983, but it’s only during the nineties that its use became widespread in the average Western households. So what does it mean today to still talk of the Internet as a medium while it now informs almost every thing and every thought?

“Future art historians will mark the 1994–95 season as the year the art world went online.”6 “But what if we thought about the ‘on’ of ‘online’ not as a location but as a kind of being attuned, as in being turned on or being on trend? What if instead of an escape from being ‘in real life,’ we think of the internet as a genre or style? ‘Online’ can be seen as structuring an entire way of being in the world. Akin to goth or punk or any number of cultural identities, ‘online’ can be thought of as a way of doing things, not the place they are done. […] To imagine ‘online’ as a place we can go is also to indulge the fantasy that we can simply choose to leave it behind, or refuse to go there. But we are always in the midst of the ‘online’ way of being, whether we are looking at a screen or not.”7

The digital is our cultural condition, there is not much doubt about that. The question then is reduced to how you address it, how you choose to position yourself in relation to it.

“One might query any contemporary artist and, as a kind of litmus test, ask the following series of questions: Do you think of yourself as primarily working ‘on’ the digital or primarily ‘within’ it? Is the computer incidental to your work, a tool like any other? Or is the computer at the heart of what you do? Shall art orient itself toward the digital? Or shall art merely live inside the digital, while concerning itself with other topics entirely?”8

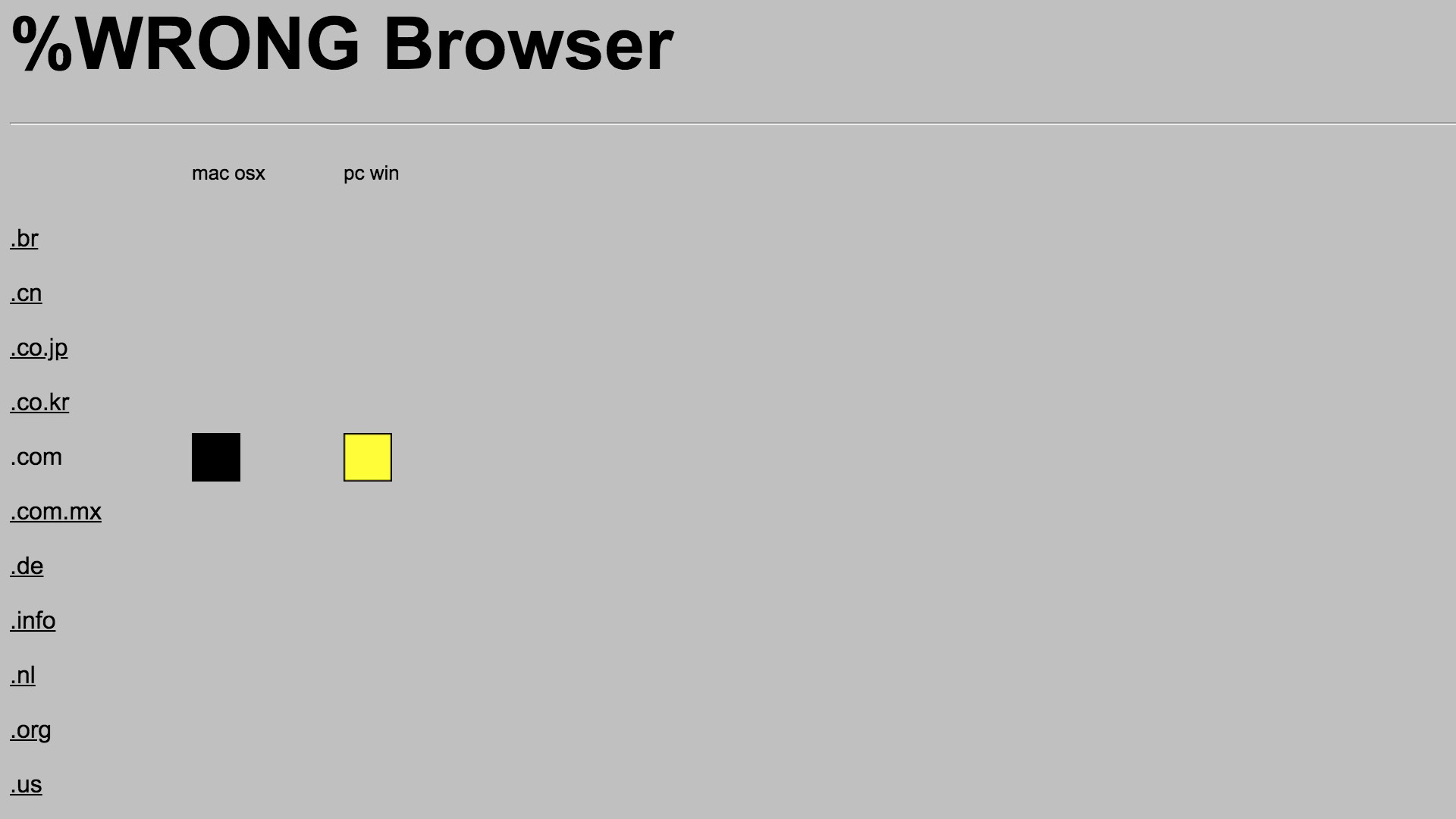

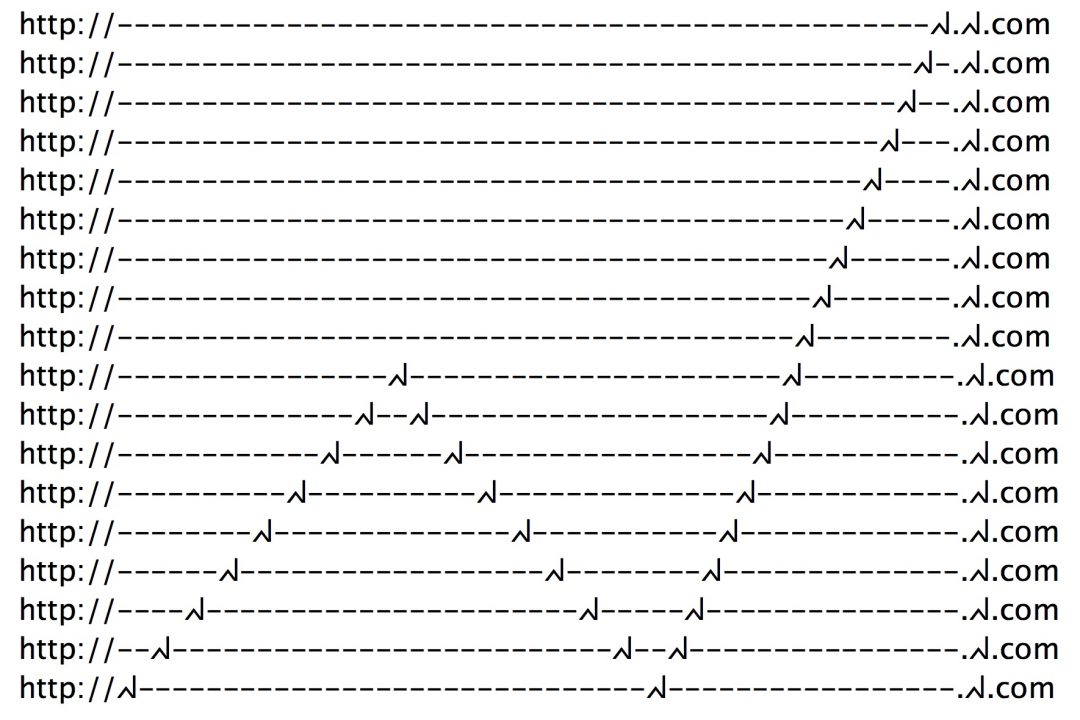

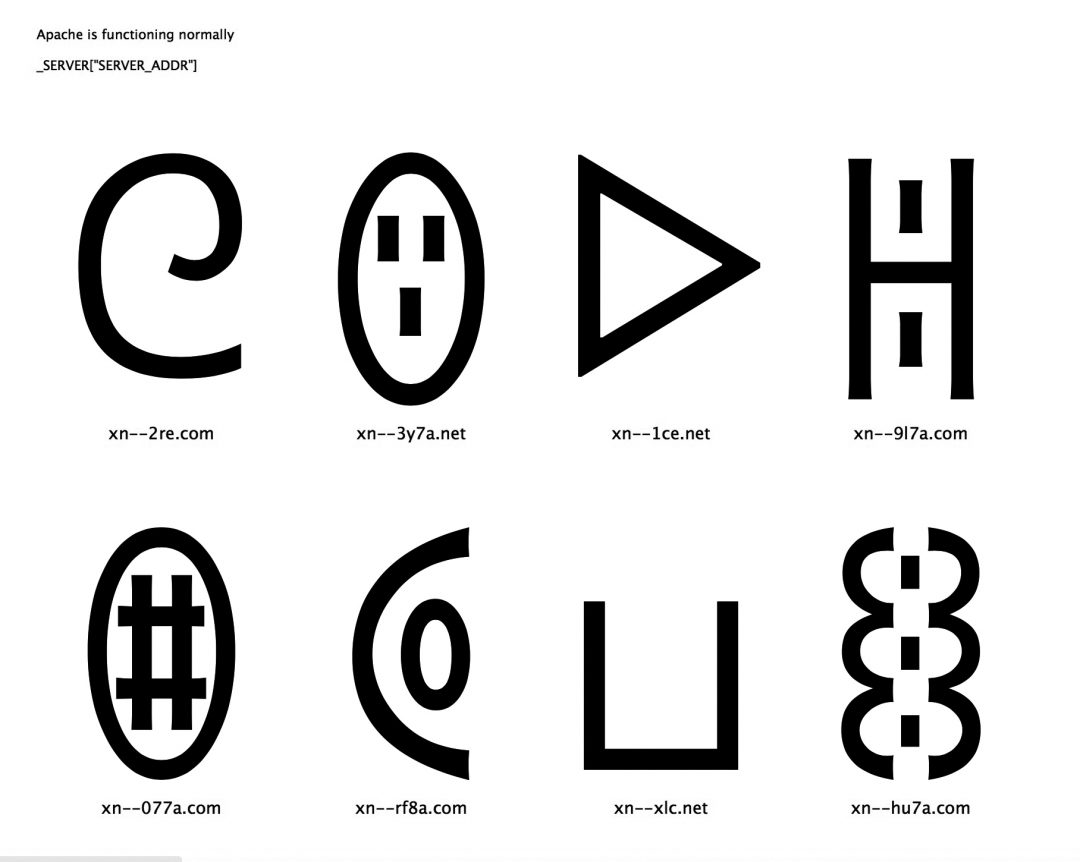

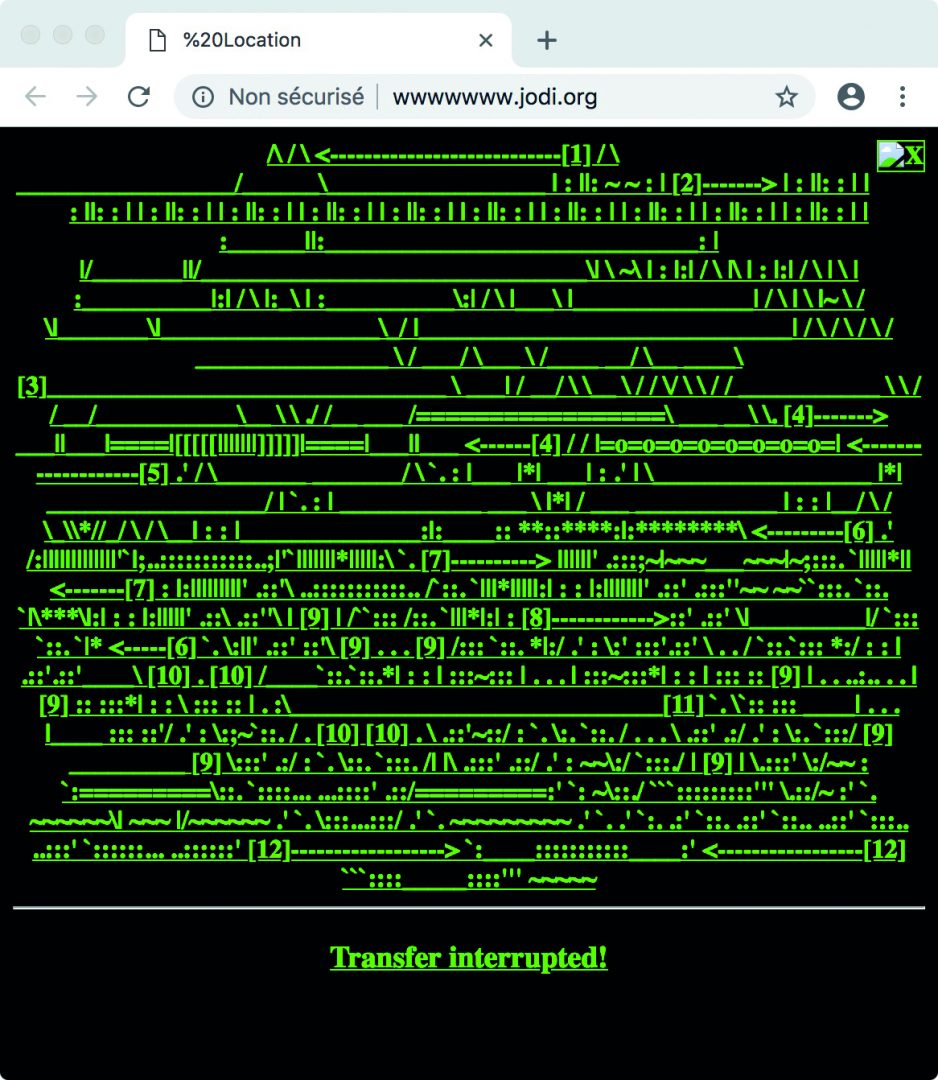

Following the thought Alexander R. Galloway developed through his study of JODI’s work, we can indeed consider the relation of art to the net as unfolding into two tendencies: the net as a medium, and the net as a context. There would thus be the modernist one, self-referential and at times even autotelic—that is to say the somewhat cliché idea one can have about net art being an appropriation or a misappropriation of the technical settings and possibilities of the web—offering a highly formalist reflection on its own matter, in both senses of the term. A reflection perfectly exemplified by the work of these aforementioned early net.artists. JODI started to work in 1991 on local computers through CD-ROMs before switching “to the distribution medium of the web”, “leaving the art system aside and learning from the local television a lesson taught by video artists from twenty years before that you could work against television by making alternative formats of television and broadcasting them on local channels”9 and applying it to the web, claiming the browser window as their canvas.

The second tendency, the “non-modern, be it premodern, postmodern, or some other alternative”10, in a reverse movement, takes itself as the point of departure and not as the end of the road, if we can say so, and the network it is interested in is not only the online one. As early as 1986, Gene Youngblood stated that “The only relevant strategy now is metadesign—the creation of context rather than content.”11 If the two tendencies coexisted from the beginnings of what had soon been called net art12, the second was, and still is, largely dominant in the field. As much as it is is easy to see JODI as a paradigm for the medium oriented one, it is sisyphean to look for one for the context oriented one, as diverse and immense it is, but if we really have to come up with a name, in a sort of historic equivalence to JODI, then we would mention Heath Bunting. HisLondon Pirate Listening Station (1999-2009), as an example, allowed to listen to all the pirate radio stations in London from everywhere in the world, remotely connecting people to very local and specific content, in an allegory of the very essence of the World Wide Web: “I have had two major threads in my work. One is communications or networking or whatever you want to call that. For years I have been doing things with sending things in the post or via fax or just somehow trying to create theatrical spaces in the street and then the other side to my work is creating meetings, where other people can do things together. […] In the city I used to live in, Bristol, I was well known there for many years for doing these things. But I wasn’t well known in Amsterdam then, for instance, where I am now. That is the power of the Internet.”13

“The art of networking goes beyond the idea of media as containers, and it should be interpreted as a conceptual work, in which what counts is connecting; subverting the idea of art that is created by a single person.”14 “Modern art created the aesthetic object as a closed system in reaction to the machine-based industrial revolution. Postmodernism created a form of art as an open system of signs and practices in reaction to the postindustrial revolution of the information society. At the moment, net art is the driving force most radically transforming the closed system of the aesthetic object of modernism into the open practices of postmodernism…”15 If “Net-based art is the ‘last avant-garde’ movement at this point in time, both in terms of the way it sees itself and with regard to its historical context”16 net art, as we saw, is not only a site specific form bound to the Internet. It expands from it. “My thesis is that the net was absorbing a collective desire which peaked between 1989 and 1991, and that very soon it became a everyday medium. The question is how to relate it to the ‘outside’ where times are definitely getting harder and more unequal. How to define the net as a political tool without neglecting its potential for polymorphous imagination and aesthetics, and so on…”17 “This development took place in an autonomous situation as unusual for the media as it was for the art world at the time; the frameworks were not only independent of any art institution, but also existed outside of state or commercial media control.”18 “Most of the net.art current was propagated through collective platforms. […] mailing lists such as <nettime> are a concrete example of this.”19 “It must be stressed that communication was always simultaneously conceived as art production. The idea was to contest the demagogic leveling function of the mass media with a utopian and anarchic principle of sharing and of collective, discursive, and participative design.”20 “This […] kind of autonomy—unstable and ephemeral—contradicts the ideal put forth in the history of modernism: that of an absolute, individualist, artistic-aesthetic autonomy, a bid for eternity made the leitmotiv of modern art by Charles Baudelaire, Clement Greenberg, and the art-market boom of the 1980s. It was precisely this kind of ‘art for art’s sake’ autonomy that the early Net-based art sought to overthrow or discredit in favor of a supra-individual, discursive, processual, networked, collective art that, like the notions of ‘metadesign’ or ‘social sculpture’, was not representable in the form of a simple, stable ‘work of art’.”21 “Net art activity is a composite phenomenon consisting of Net conditions (bandwidth and protocols), hardware conditions (computer, monitors, etc.), and software (server, script interpreter, etc.); furthermore it is based on dynamic exchange—on sharing—and hence on participation. It is essentially active, caught up in the process of (technological and social) exchange, and only materializes under specific Net conditions. A final and particular feature of Net art activity is that, in the process of its performance, it shares or is shared and multiplies, and because of its inherent presentational form, (i.e. the Net itself), it is always contextually enacted. ”22

“We should not be surprised that both trajectories — the development of modern media and the development of computers—begin around the same time. Both media machines and computing machines were absolutely necessary for the functionning of mass societies. The ability to disseminate the same texts, images, and sounds to millions of citizens—thus assuring the same ideological beliefs—was as essential as the ability to keep track of their birth records, employment records, medical records, and police records. Photography, film, the offset printing press, radio, and television made the former possible while computers made possible the latter. Mass media and data processing are complementary technologies; they appear together and develop side by side, making modern mass society possible.”23 “Social networks are reflections of social structures in software.”24 “In the 1990s, the term ‘network’ resonated with non-hierarchical communication, with distributed relationships that mysteriously interwove to create a tear-proof texture, nevertheless fluid and dynamic, and, if nothing else, with the ability to challenge and undermine rigid and hierarchical power structures. At the same time, it remained a form that was elusive and susceptible to obfuscation, which, in combination with political concerns, could feed suspicions. […]

Manuel Castells has suggested the term ‘networked individualism’ for an evolving social pattern that allowed individuals to form ‘virtual communities, online and offline,’ […]. What this term tries to grasp is more than just a way of getting organized. It is about dissolving the old dichotomy between the individual and the collective/community in order to bring about more than just a collection of isolated individuals. […] It was Rosie Braidotti who, as early as 1996, spoiled the party when she wrote that the large scale of the digitization of society would mainly lead to an increasing ‘gender gap’.” 25 “The acceleration in developments in science, technology, communication, and production that began in the second half of the twentieth century and that has condensed into the concept of the digital has resulted in what might be the most contradictory moment in human history. On the one hand, the advances in the productive forces of society have made it more possible than ever not only to imagine but to realize a world in which the tyranny of social inequality is brought to an end. On the other hand, despite the potential productivity of human labor, the reduction of these developments to an unprecedented level of accumulation of private profits means that rather than the end of social inequality we are witness to its global expansion. The digital world, in other words, is the site of class conflict.”26 “The network and the networked individual, once the embodiments of new forms of resistance, now have become the basis for new forms of exploitation and oppression.”27 “In general, now I am having mixed feelings about early net art because I see how the strategies developed by net artists are now used by corporations and in politics. But that’s the destiny of avantgarde art—developing communication and aesthetic tools for the future capitalists and politicians.”28

“The arbitrary relation of signifier to signified breaks down visibly in Net phenomena. Digital artifacts stand for nothing but themselves, because operations are conducted on and with them, and not with ‘originals’—the ‘sources.’ […] However, art forms whose reception can only occur against a certain event backdrop, as is the case with Net art, can only enter the institutional context as documentation. Precisely when the exhibiting institution successfully applies its systemic conditions and enforces requisite assimilation, the system’s constituent concepts no longer consistently hold—for neither work nor original is actually exhibited. Should institutions prove unable to resolve these paradoxes, the Internet will sooner or later assimilate them and write or enact its own history.”29

1 The Eternal Network is a concept developed byRobert Filliou and Georges Brecht in the early 60’s.

“The network is everlasting”, “there is no more art center now”, “the network works on his own” as Filliou often repeated.

2 No Internet, No Art, A Lunch Bytes Anthology, edited by Melanie Bühler, Onomatopee, 2015, p. 9.

3 We will refine the confusion between net art and digital art later on, see note 12 et sq for instance.

4 When he was asked to design a poster to advertise for an Internet-related event he was hosting in 2012, Douglas Coupland came up with this slogan that quickly became iconic.

5 The publication of an article by Coupland himself two days after I wrote this question, in which he stated: “to be honest, the truth now is: ‘I NO LONGER REMEMBER MY PRE-INTERNET BRAIN’. ”was a beautiful coincidence. https://edition.cnn.com/style/article/douglas-coupland-internet-brain/index.html

6 Dieter Daniels, “Reverse Engineering Modernism with the Last Avant-Garde” in Dieter Daniels, Gunther Reisinger ed., Net Pioneers 1.0, Contextualizing Early Net-Based Art, Sternberg Press, 2010, p. 19.

7 Nathan Jurgenson, Rob Horning, Alexandra Molotkow, and Soraya King, “Extremely Online”, Real Life, January 16, 2018, http://reallifemag.com/issue-extremely-online/

8 Alexander R.Galloway, “Jodi’s Infrastructure”, e-flux journal #74, June 2016, http://www.e-flux.com/journal/74/59810/jodi-s-infrastructure/

9 JODI in “Apache is functioning normally” a talk given at 33C3, Hamburg, December 29, 2016,

9.1 “on occasion artists are able to compete with computer researchers, rather than simply creating new demos for commercial software, thus functioning as ‘memes’ for computer industry.” Lev Manovitch, “The Death of Computer Art”, Rhizome, 1996, http://rhizome.org/community/41703/

10 Alexander R.Galloway, “Jodi’s Infrastructure”, art.cit.

11 Gene Youngblood, “Metadesign: Towards a Postmodernism of Reconstruction,” abstract for a lecture at Ars Electronica, 1986.

12 “Art created with the internet would simply be called media art, or electronic art, terms which don’t cover specific network issues as well as net.art does, with or without the dot.” Josephine Bosma, “The dot on a Velvet Pillow. Net.art Nostalgia and net art today” published in the catalogue of the exhibition “Written in Stone, a net.art archeology” held at the Oslo Museum of Contemporary Art in 2003. http://lists.artdesign.unsw.edu.au/pipermail/empyre/2003-April/msg00010.html

12.1 “The medium of net art, however, is simply the net: whichever particular form net art takes is irrelevant for its definition.” https://transmediale.de/content/webvideo-the-new-netart

12.2 The label “net.art” (with a dot) usually refers only to a small group of artists of a particular time (1995-1999) notably comprised of Heath Bunting, Vuk Cosic, Alexei Shulgin, JODI, and Olia Lialina.

12.3 “What is net art? Since the beginning of the net itself, there has been an intense discussion about this question. You will find definitions everywhere on the net, and even if there is some agreement, the definitions vary. […] The very strict definition is this: net art is art that cannot be experienced in any other medium or in any other way than by means of the network. […] And finally, the very loose definition: net art is art that deals with ‘the net’ and all that the net is about (chat, economics, distribution technology, copyrights, browsers, cookies, big-time corporate mergers, etc.), regardless of medium. In this sense William Gibson’s novels are net art.” Andreas Brogger, “Net art, web art, online art, net art?”, 2000, http://www.afsnitp.dk/onoff/Texts/broggernetart,we.html

13 Josephine Bosma, “Ljubljana Interview with Heath Bunting”, June 1997, http://www.josephinebosma.com/web/node/40

14 Tatiana Bazzichelli, Networking, The Net as Artwork, Digitial Aesthetics Research Center, Aarhus University, 2008, p. 29.

15 Peter Weibel inPeter Weibel, Timothy Druckrey, Net_condition, Art and Global Media, MIT Press, 2000.

16 Dieter Daniels, Net Pioneers, op. cit., p. 20.

17 Pit Schultz, October 8, 1996, http://neoscenes.net/projects/me/texts/schultz.html

18 Dieter Daniels, Net Pioneers, op. cit., p. 28.

19 Tatiana Bazzichelli, Networking, op. cit., p. 29.

20 Robert Sakrowski, “Net Art in the White Cube—A Fish on Dry Land”, Net Pioneers, op. cit., p. 220.

21 Dieter Daniels, Net Pioneers, op. cit., p. 29.

21.1 “Also most of the works are very, if not fully, dependent on the context in which they are viewed if they are to function as intended. Think of works in domain names, works that exist on video or blogging services, generative works etc. ” Constant Dullaart, 2012, https://www.net-art.org/netartdatabase

22 Robert Sakrowski, Net Pioneers, op. cit., p. 216.

23 Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media, MIT Press, 2001, p. 22.

24 Robert Sakrowski, “Identity and Social Networks”, Shirn Mag, 2005, http://www.schirn.de/en/magazine/context/identity_and_social_networks/

25 Cornelia Sollfrank, “on cyberfeminism then and now”, 2017, https://transmediale.de/content/revisiting-the-future

26 Rob Wilkie, The digital condition, Class and Culture in the Information Network, Fordham University Press, 2011, p. 2.

27 Cornelia Sollfrank, “on cyberfeminism…”, art.cit.

28 Alexei Shulgin and Josephine Bosma in Conversation, “A Net Artist Named Google”, Rhizome, January 12, 2017, http://rhizome.org/editorial/2017/jan/12/a-net-artist-named-google-1/

29 Robert Sakrowski, Net Pioneers, op. cit., p. 214-215-216.

29.1 “To draw the comparison with Performance Art again, I felt as if people were trying to archive the body of the performer to be able to archive the work. As if you would freeze Marina Abramovic. In collaboration with Robert Sakrowski, art historian, former head of the Netart-Datenbank.org at TU Berlin and currently running the initiative Curating YouTube, I am making a template for how to document your own private usage and viewing of Internet-based Art.” Constant Dullaart, 2012, https://www.net-art.org/netartdatabase

29.2 “As David Ross has noted (in a text attempting to establish ‘21 Distinctive Qualities of Net.Art’), there is often a high degree of intimacy between the user and the art on the web. We can view it, and use it, in our home.” Andreas Brogger, “Net art, web art, online art, net art?”, art.cit.

29.3 “rejection of Net-independent, real-space realization in the art world is often an integral and deliberate component of the works.” Robert Sakrowski, Net Pioneers, op. cit., p. 217.

Image on top: JODI, Wrong Browser, 2000. http://wrongbrowser.com/

- From the issue: 89

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Algocurating,

Related articles

Some white on the map

by Guillaume Gesvret

Toucher l’insensé

by Juliette Belleret

An exploration of Cnap’s recent acquisitions

by Vanessa Morisset