Corentin Canesson

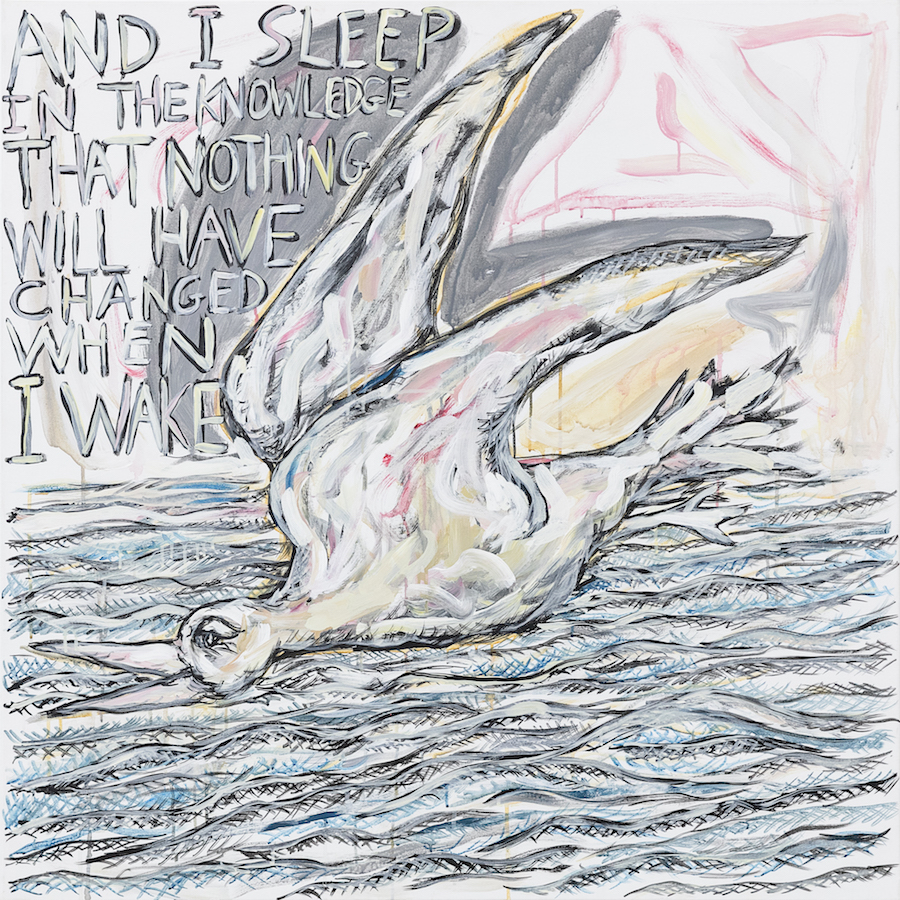

It looks like a set list: 1. What a night to be Born 2. Ultra Slave 3. Then Love takes us to faraway places. Titles of canvases which sound like a succession of alternative rock or post-punk songs. The pictures they describe1–large format works split between colourful abstract flat tints and figurative compositions–share this in common with the musical genres they involve as references that they are incorporated in a history which is always written with the prefix “re”. As at certain concerts, you have the impression of knowing the tune but you cannot precisely identify it. Is it the remake of a standard hit from the 1960s? Or else the spectre of a band from those times which is still haunting new productions? These things that people say about rock and its sub-genres have been said about Corentin Canesson’s painting, particularly in relation to his first two solo shows at Passerelle (2015)2 and at the Crédac (2017).3 A few years later, it is interesting to see how, within this abstract and figurative repertory that is being forever re-worked, the painter has developed a set of motifs and signs which are often borrowed, and nevertheless represent his hand. The bird–a long-billed wader with a twisted neck–has remained, just like the erotic scenes and the figures of naked painters standing in front of their easels. The snippets of writings, too, drawn in capital letters outlined in black, taken from songs and poems. Corentin Canesson develops these motifs in relation to the finances of the moment, often to do with the exhibition in the offing. The budget will determine the number and format of the canvases, which will in their turn define the scale of the motif. Some, what is more, display their subordination to the context, like wading birds contorting themselves to fit into the frame. There are a certain number of birds, painters and so on, but it is difficult to talk in terms of “series”, because Corentin Canesson does not necessarily paint them one after the other, nor does he always try to hang them side by side. On the other hand, his latest hangings at the DOC4 and at the Fondation d’entreprise Ricard did not appear to be trying to exhaust the motif (like Josh Smith and his successions of fish), but rather to surreptitiously preserve its comeback, the way one works in the interstices of chorus. At the DOC, out of two rows of ten pictures, Corentin Canesson composed a sequence that alternated abstract canvases–some Expressionist, others covered from top to bottom by oblong forms–with studio scenes. Letting your eye travel along the row of pictures, you could get the impression that the outlines of the figures in a canvas became unravelled in the nearby abstraction, as if, in the meantime, their lines had become blurred, taking on an identifiable form a few canvases further on. The hanging organized an equilibrium in saturation, with, in the middle, chorus and coloured Larsen effects. And you could see on the wall a projection of the mess in the artist’s studio, located a few floors up, where, on a daily basis, every manner of painting seems to need another to hold up both physically and conceptually.

The weight of acrylics

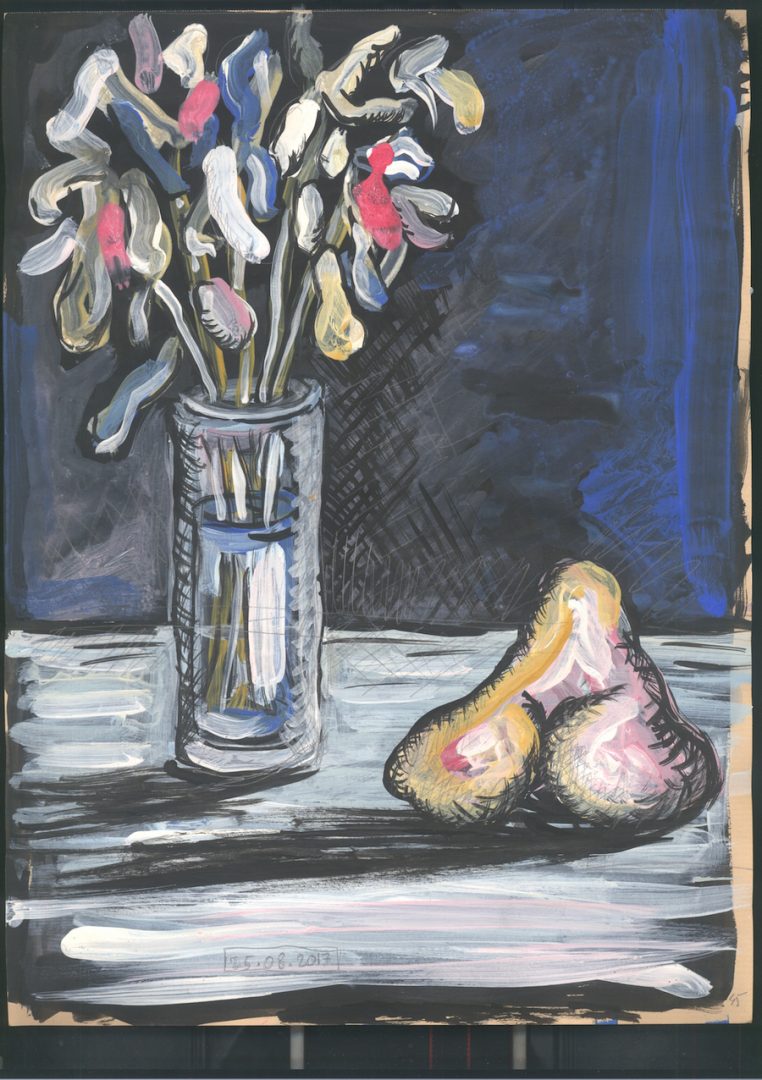

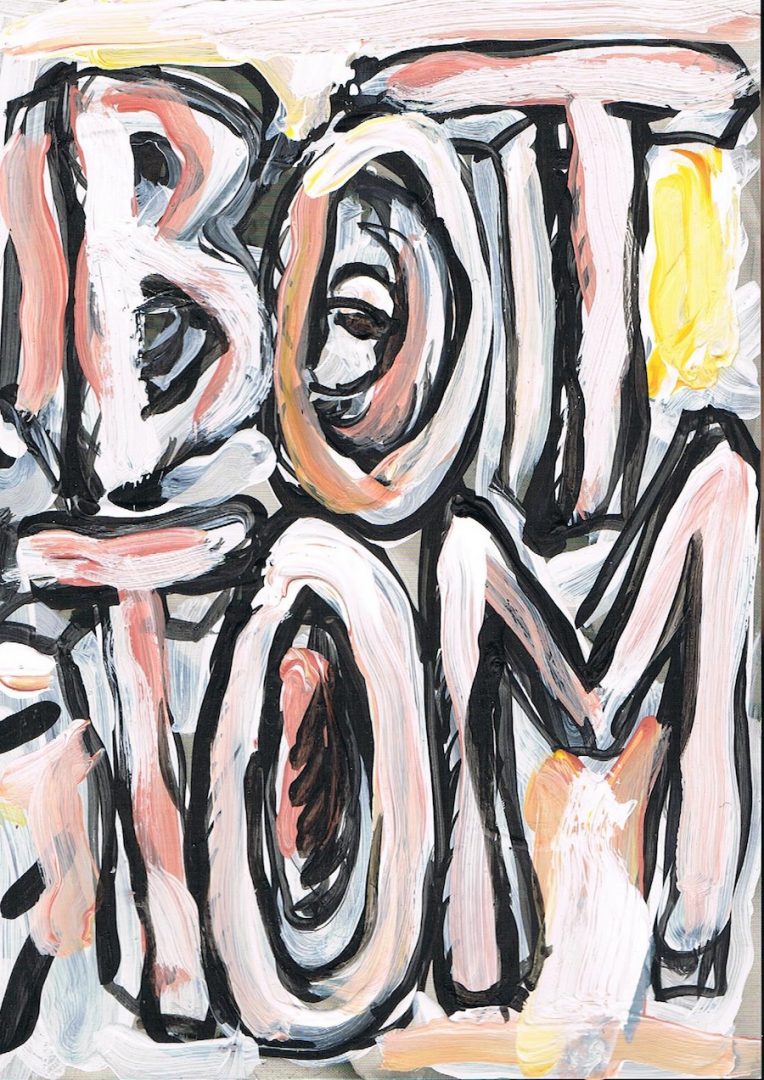

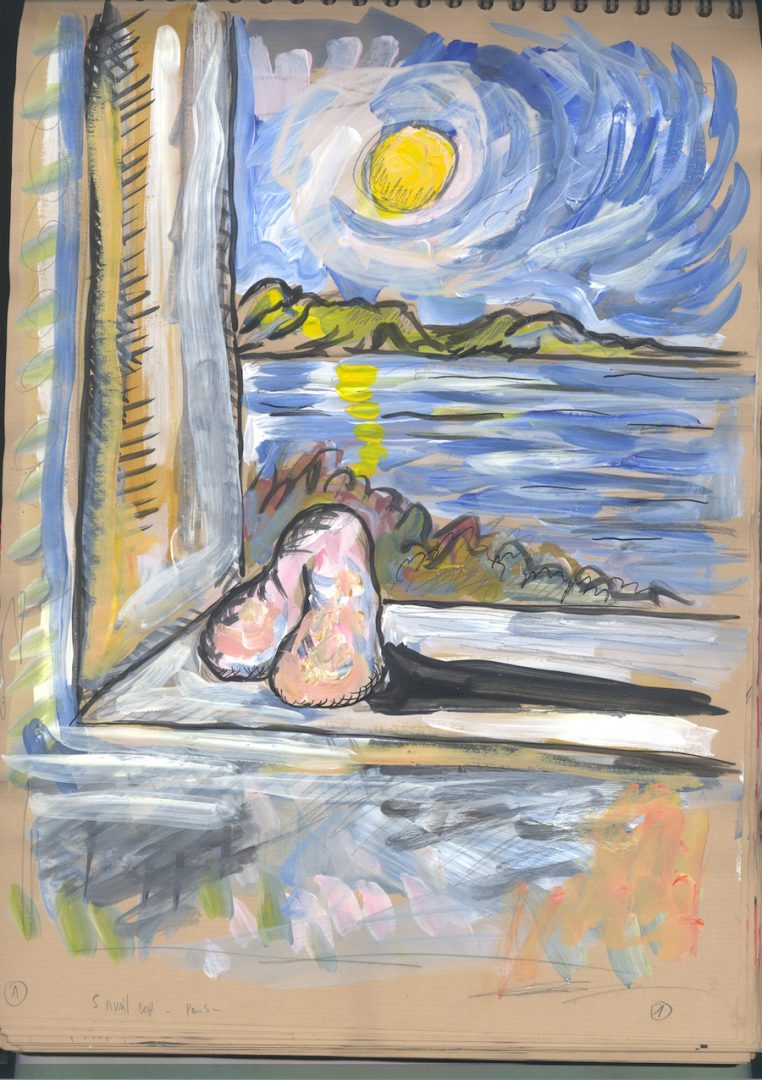

Corentin Canesson says that over these last few years of studio work, his figuration has become “heavier”. The–pre-constructed–drawing of his figures has gained in precision and, in a sort of permissive shift, the painter has left more room for flesh–colour and representation–, for figures and for the paste-like, not to say “crust-like” effect of the accumulation of layers of paint. At the same time as the painting becomes heavier, the term “Bottom” has become a passing emblem of the artist, who included it on his 2018 invitations to the show of the same name at the Nathalie Obadia gallery5, and wrote it in upper-case letters in a series of works. Over and above the reference to Robert Wyatt’s “Rock Bottom” album, it is as if the canvas were expressing its own heaviness, as if it were moved from the bottom–of the body or history. The series Les couilles d’Adam [Adam’s Balls] seems to insinuate the same thing.

The motif presented in twelve versions on paper is a pair of hanging testicles, avatar of a soft masculinity traversing the ages of painting. One pair is portrayed at the foot of a window opening onto a landscape in the Renaissance tradition; another swells with a post-Surrealist exhalation. Beside a bunch of flowers, they incorporate the still life status; they are derisory and starched, like the styles they borrow turn by turn. If Corentin Canesson’s painting has become so heavy, this is probably because it has increased its faculty of absorption; of styles, inevitably, to such a degree does he pursue the gestures and the chromatic range at work in the painting of Bram Van Velde or Philip Guston (among so many others), but also of influences outside the medium. In this way he incorporates in his canvases the anthems of post-punk songs and, more recently, fragments taken from René Ricard’s poetry. The snippets of texts painted in capital letters see their outlines duplicated, and their interiors weaving a mixture of colours. These canvases are probably the most “vitalist”–in the sense intended by Isabelle Graw–, because they are loaded with the writing of their creator, they betray his presence, a belief to which the theoretician attributes the unflagging success of the medium.6 Paradoxically, precisely where the brush strokes were undeniably meant to beckon towards the painter’s presence, the voices and the styles which this latter borrows help to better deform his own outlines. The persona behind the canvas is multiple and claimed, especially when Corentin Canesson invites his friend Damien Le Dévédec to draw what he will subsequently paint.

Depressive hedonia

Last September, Corentin Canesson exhibited at the Fondation d’entreprise Ricard a series of five large canvases in the midst of which pride of place was given to an orgiastic re-interpretation of Bosch’s Ship of Fools, all in flesh-hued figures. While a reddening Van Gogh-like sun sets over water treated with painstaking touches of colour, the ship has fun, singing and fucking. And nobody seems to notice that a man is drowning. Corentin Canesson here pushes the cursor of stylistic and historical compression to another level, treating the classic example of mediaeval painting in an Impressionist style steeped in Maria Lassnig’s pinks and greens. A “colourful painting of everything that has ever been believed”7—such is the definition that Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari give of capitalism, from which, according to Mark Fisher, a form of generational “depressive hedonia”8 results, in the face of the relentless end of history, which its economic and ideological logic has imposed. Beyond the facile link that can be established between the overall end of history and the end of a medium caught in a mechanism of re-appearance and flattening, this affection peculiar to a condition that is constituted “by an inability to do anything else except pursue pleasure”9, driven by the perpetual impression that “something is missing”10, is released from Corentin Canesson’s praxis. The painter asserts that the quest for pleasure is a driving force for painting and re-painting canvases which he says he laughs at in his studio, while at the same time making room for a form of melancholy, for rock music and René Ricard’s poetry. “I just want you to stay”, we can read beneath a motif in the process of vanishing behind a coat of white paint. In a small acrylic painting on paper, titled Le modèle et son peintre [The model and their painter] (2018), a feeling of the end of a game and a pleasure in painting are married in the blissful and disconcerting smile of the artist who, in front of his gaping canvas, seems to be enjoying his stereotypical posture. Like Kurt Cobain, Corentin Canesson’s “first artistic commotion”, whose portrait he painted at the Tôlerie in early 201911, the artist is aware that “his slightest gesture [is] a cliché written in advance, that even such an awareness stems from cliché”.12 Instead of disarming him, this observation seems to bestir him. He choses to let himself be eternally haunted and to enjoy haunting his predecessors. In the picture, Kurt Cobain wears the T-shirt of Corentin Canesson’s rock band. He and his friends have named it The Night he came home.

1 Paintings shown at the Fondation d’entreprise Ricard as part of the group show “Le Fil d’Alerte”, 21st prize of the Fondation Ricard, 10 September – 26 October 2019.

2 “Samson et Dalila”, Passerelle, Brest, 7 February – 2 May 2015.

3 “Retrospective my eye”, Crédac, Ivry-sur-Seine, 20 January – 2 April 2017.

4-“DOC Printemps 2019”, DOC, 7-12 May 2019.

5 “BOTTOM”, galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris, 12 January – 24 February 2018.

6 Isabelle Graw, The Love of Painting, Genealogy of a Success Medium, Berlin, Sternberg Press, 2018, p. 20.

7 Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, L’Anti-Œdipe. Capitalisme et schizophrénie, Paris, Minuit, 1972-1973, p. 319.

8 Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?, 2009, John Hunt Publishing, Zer0 Books, p. 21.

9 Mark Fisher, op. cit., p. 22.

10 Ibid.

11 “Après Jacques Michell…”, La Tôlerie, Clermont-Ferrand, 21 February-12 April 2019.

12 Mark Fisher, op. cit., p. 9.

Image on top: Corentin Canesson, DOC Printemps 2019, with Juliette Roche, DOC, Paris. Photo : Paul Nicoué.

- From the issue: 92

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Merlin Carpenter - "What’s so elastic about you ?", Jacqueline de Jong, Celia Hempton, Madison Bycroft, Charles Atlas,

Related articles

Biennale Son

by Guillaume Lasserre

Lou Masduraud

by Vanessa Morisset

Bharti Kher

by Sarah Matia Pasqualetti