Laura Henno

Painting contemporary life: from marginal communities to strategies of resistance and survival

From the Comoros to California, from Reunion Island to Finland, from northern France to Rome, Laura Henno is both developing a seemingly documentary aesthetic which transcends genre codes, and working on deeply ethical research to do with lives which are marginal, isolated and peripheral. The photographer and filmmaker recently won the SAM prize for contemporary art—€20,000 and an exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo planned for 2021. The winning project is titled N’Dzuani, meaning Anjouan (island) in Shindzuani. What will thus be involved is overlapping the lifestyles and movements of different young people already met, be they Comoran or Mahorais (from Mayotte): Patron (Boss), who appears in the short film Koropa (2016), Smogi, in Djo (2018), and the “Boucheman”, illegal immigrants living in the heights of Mayotte, whom the artist has been following for several years, and who feature in the series Ge ouryao! Why are you afraid! (2018). Recapitulating research carried out over time, the project incarnates the themes that have been exercising Laura Henno, and which she has been at work on for more than a decade, and through which life narratives meet history with a capital H.

When she examines adolescence, in all its fragility, anxiety and expressiveness, especially in the series Land’s End (2001-2009), Laura Henno uses mise en scène presentation and non-professional models: as encounter follows encounter, she chooses young people by their looks, physique, and energy, with a view to getting them to pose using a process of waiting, right up to the shot itself, which tallies with the energy imagined by the artist. Then, after a residency in a medical psychology centre for teenagers in Dunkirk, the photographer tries out another way of going about things, starting from the narratives of the young people, their unusualness and specialness, their anxieties, their ailments and their relation to the body. This project was extended and became a permanent part and parcel of the work carried out on Reunion island, re-created in particular in La Cinquième Ile (2009-2012), with teenagers from Mayotte and the Comoro Islands in exile.

Laura Henno’s œuvre is developing within an incarnated vision of youth and interstice, through the figure of the young migrant, on the one hand, and makeshift communities on the other—teenagers, isolated minors, young illegal immigrants, squatters, and people living in wretched poverty, all represent the artist’s favourite subjects as she explores the notions of not-belonging, displacement, margins, and the strategies of resistance and survival which are constructed in such communities. But far from exploiting or commodifying the people photographed, each one of the works is developed based on a principle of dialogue, that of encounter and exchange. Each series is the outcome of an immersive project during which a link with the referent is developed: a relation of mutual trust, respect and hospitality, within the context of a real sharing of the daily round of the groups which will be the subject of the pictures. In this sense, in addition to a visuality inherent to photographic praxis, these latter acquire the visibility which is refused them in society. From now on, they no longer issue from a mass of excluded and dispossessed people, but from a set of existences and plural voices, all living together.

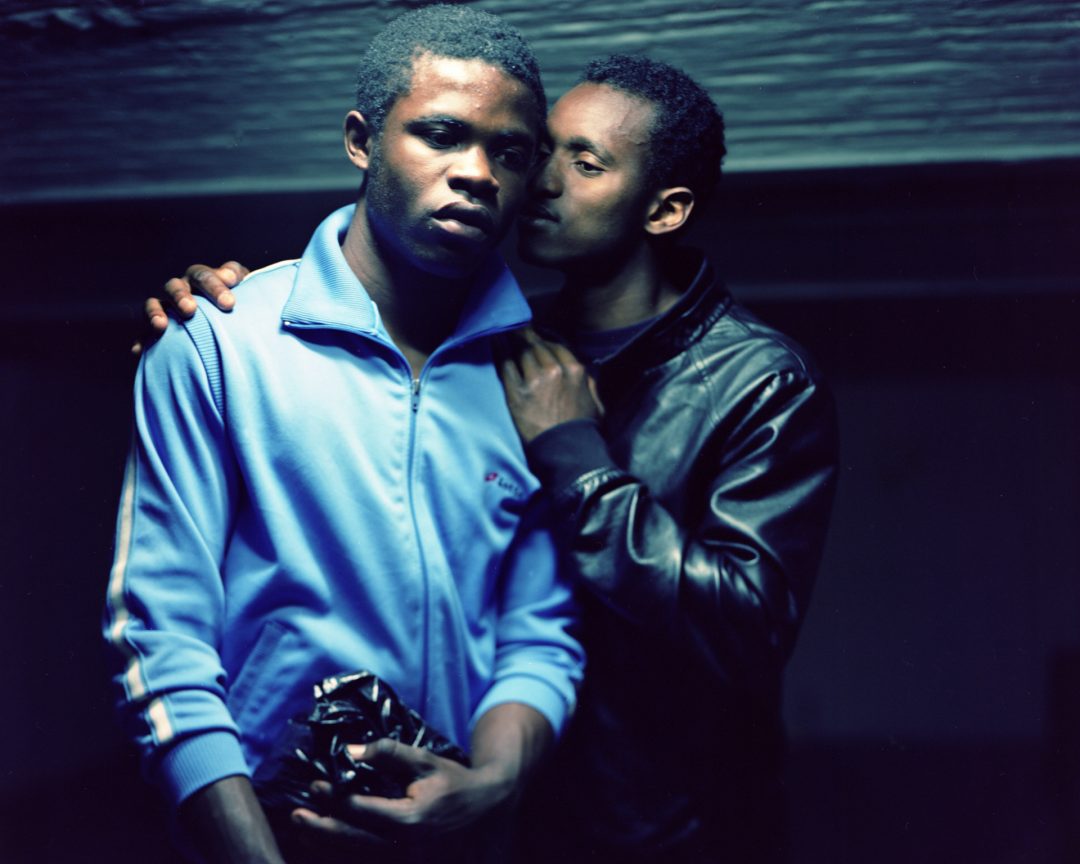

This is the case, for example, with Missing Stories (2012), which traces the artist’s cooperation with foreign isolated minors staying in the Maison de l’Enfance in Lille. Discussion is the fount of all creative work here: getting rid of their mistrust and anxiety, the young people interested in the project will shape the aesthetic approach, by sharing their experience. The documentary method is henceforth tinged with a fictional element, connected with the narratives collected. In fact, to assess their situation as minors unaccompanied by a legally responsible person, the administration asks the teenagers to provide a detailed essay in which they must describe their itinerary. The complexity of their condition corresponds to the complexity of narrating at times traumatic experiences: there must be a link with expectations, while at the same time presenting readers with a certain intimacy, somewhere between snippets, traumas, modesty, lies and grey areas. A fragile narrative thread appears, transcribed in the image and describing the encounter with these young people. The photo titled The Story Teller is, in this sense, emblematic as a result of the dovetailing of interpretations which it ushers in, and the formal beauty it gives off. Two young people are presented by the photographer, one facing the camera, staring into space, with an expression of doubt and expectation, the other whispering something into his ear. The composition of the image refers to a pictorial work, anchoring Laura Henno’s approach in a research that encompasses the arts: an affiliation with Baroque painting stands out through the contrasting interplay of light and shadow, veering towards chiaroscuro, the intensity of the differing shades of blue and the dramatic tension which conveys the mystery shrouding the secret handed on by one of the boys. Is this an invitation to lie? Is the whisperer playing the part of the prompter with regard to the intimate tale to be told? Or is it just a teenage secret? The presentation of the protagonists sublimates the stories and the visual approach gives rise to a poeticization which does not, however, spill over into indulgence or fascination with the tricky condition of exiled young people.

Just as the migratory itinerary may result from an experience of dispossession, the situation of the inhabitants of Slab City, to which Laura Henno devotes a project in progress, made up of a series, Outremonde (2017-2018) and a film, Haven, is akin to the experience of exile. The occupants of the place have in fact made the choice to move towards a no-man’s-land in southeast California, a desert area with no access to public services. The caravans, which are disembowelled and patched up, thus attest to the same roaming of this white community which has nevertheless become sedentarized. The extremely religious group, which appeared in Gianfranco Rosi’s Sea Level (2008), appears by way of contextual portraits in which landscape is as essential as people. In the images, the natural light and the use of pastel colours seem to soften the wretchedness, and the depiction of the characters seems to have acquired an aura akin to the sacred, calling to mind the significance of religion in this encampment where the State is totally absent.

By focusing on an isolated group of people, Laura Henno underscores the organization of a community based on forms of fellowship, which is exciting, alive, and creative. This shared life, on the sidelines, stems from a certain form of resistance, in the quest for autonomous survival. This strategy lies, incidentally, at the hub of the artist’s research in the Comoro archipelago, in the more anxious prospect of migration as contemporary marronnage (the state of escaped slaves or ‘marroons’). The time-related dialectic at work in Slab City, in the almost utopian representation of a community that is outside the world, becomes, in the Indian Ocean, a reading of history that is capable of grasping the identity-based complexity of these island territories.

As post-colonial territory, both the Comoro Islands and Reunion Island are marked by slavery. Marronnage—the phenomenon of runaway slaves—leaves traces, and has known different forms of updating, in the contemporary context, involving extreme poverty and an ongoing flow of migrants. The figure of the “nègre marron”—the ‘marroon’ or runaway negro slave—, the fugitive if ever there was, re-emerges in the idea of exile, where it may, in the same way, involve working out plans for rising up against domination and oppression.

The further development of this very varied reality, somewhere between crisis and survival, likens Laura Henno’s work to that of Mohamed Bourouissa in the way the two observe marginal spaces, and forms of resistance and transgression constructed in them. Two aspects which, on the face of it, seem to be opposed are represented thus: the image of the teenage smuggler in Koropa and M’Tsamboro, and the migrant, cut off from society, living in a community of men and dogs on the beach, a place duplicating the marginalization involved by the island context, especially in Ge ouryao! Less easy to broach than the image of the illegal immigrant, that of the young smugglers, who are supposed to run fewer risks with the border police because they are minors, illustrates a confinement in an endless cycle of exile: the teenagers are as if caught in the interstices between permanent comings and goings. The traffic created by the population movements is revealed, contrary to all expectations, as a survival strategy.

While emphasizing the distinctive and special features of the populations, narratives, fantasies and popular beliefs that are summoned, Laura Henno extracts the essence of the subjects she confronts and reminds us that, beyond all stereotypes, increasingly unstable situations are being erected, along with a very raw reality. Political subtlety also creates the strength of this work; if the images are not accompanied by a militant discourse, their agency is still of consequence. What is more, the large formats invite us not as much to contemplation as to develop a fiction around the images as well as an opinion about the situations pinpointed and literally enlightened by the artist.

1 Laura Henno incidentally took part in the exhibition “Désolé”, curated by Mohamed Bourouissa at the Galerie Edouard-Manet in Gennevilliers in 2019. With varying praxes, the exhibition encompassed a sort of ‘zeitgeist’ of our contemporary situation by dealing with issues of minorities and identities, migration, discrimination and otherness.

Image on top: Laura Henno, Sans-titre, « Ge ouryao ! Pourquoi t’as peur ! », Mayotte, 2017-2018. C-print, 120 × 155 cm. Courtesy Galerie Les Filles du calvaire, Paris.

Related articles

Shio Kusaka

by Sarah Matia Pasqualetti

Julian Charrière: Cultural Spaces

by Gabriela Anco

Céleste Richard Zimmermann

by Philippe Szechter