Nora Turato

A slender silhouette cuts through the crowd and becomes motionless. With her bleached hair, she is wearing a chic and eccentric outfit: a leopard-skin jacket and fluorescent green thigh boots—from Balenciaga, someone whispers in my ear. The people present have gathered around her, forming a perimeter which she starts to walk around. The situation might resemble a rap battle, but she remains on her own inside the circle. We realize that it is in reality the audience that she is preparing to challenge and provoke. Then begins a monologue with a crazy pace, from which springs a flow of words, spoken and sung turn by turn, launching us into an extremely intense acoustic experience.

The scene takes place in a Paris apartment during the International Contemporary Art Fair (FIAC), making the remake of I’m happy to own my implicit biases, a performance recently presented by Nora Turato, a Croatian artist born in 1991 and now living in Amsterdam, during Manifesta 12, in the Oratorio di San Lorenzo, in Rome. Whatever the context in which she intervenes, Turato wears the clothes (haute couture) of a persona on the verge of a nervous breakdown, a costume which seems to enable her to put herself at a remove or, conversely perhaps, have fun with an ego pushed to its extreme limit.

If the character obviously catches our attention and incorporates a part of the work in theatre, the performance resides, in other respects, in the conception of scripts which she interprets like songs. So we have a composition which does not separate words from writing, or text from music, and spreads outwards from a copy-and-paste of snippets taken from advertisements, everyday discussions, tweets, online forum comments, memes, and discussions about politics and literary works. In a compulsive consumerist gesture, she digs into the ongoing flow of data and information to find a scattered material which she de-contextualizes and re-arranges as she sees fit, lending her writings a déjà-vu aspect, without us really being in a position to identify the origin of this impression.

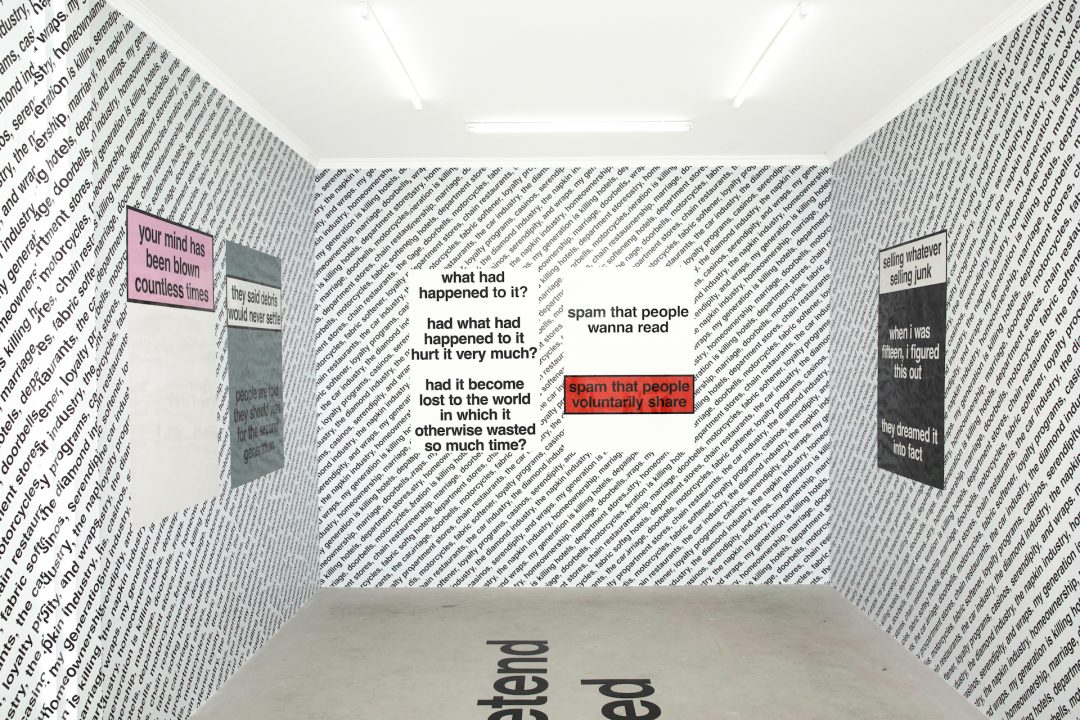

Here, clearly, we are dealing with appropriation and the literary readymade, questioning, in passing, the efficiency and scope of these terms in the digital age—do they still make sense, or, on the contrary, have they never made so much sense? The technique is not new. Let’s think of the cut-up invented by Brion Gysin and William Burroughs in the late 1950s, when they randomly cut up pieces of newspapers and put them together. In the end, however, the procedure of chaotic (re/de-)composition was more thoroughly experimented when using original literary material, produced by the authors themselves. Nora Turato’s “infospherical”1 writing is more akin to that of the American poets Tan Lin and Kenneth Goldsmith, with the latter championing a form of ‘uncreative writing’, a “writing without writing”.2 Noting the changes which the digital technology imposes on the text, they see popular culture and the web like an “ocean of language”,3 whose resources are shared and which it suffices to remove and sample like a DJ, thus, in passing, chipping away at highly serious notions to do with the auteur, intellectual property, and plagiarism. But Nora Turato contrasts an ‘ambient’ literature, as it is described by Tan Lin, echoing his musical antecedent, with a decidedly personified and situated version, a subjective posture giving rise to a winding and aggressive narrative in which private and public are merged, like on the Internet, along with personal declarations and the most varied of societal subjects, narcissism and self-devaluation, summoning sexist and cultural clichés, the better to defuse them. By accomodating a whole host of voices which she puts back into circulation by way of her own voice, her body simultaneously takes on the role of receiver and transmitter, as if she were constructing a personality based on the language of the other, while at the same time assuming and reinstating this latter through her own filters. How does language, as a common datum, act on identity and intimacy, and vice versa? What is produced by our ongoing immersion in the great media tank? Her diva figure might be described as an interface, like a kind of extremely incarnated, hypertextual palimpsest. In the ever-expanding flow of words which informs her texts and performances, Turato also draws on the material of a printed and published work. After graduating from the Gerrit Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam, she worked for several years as a graphic designer, and endows her ephemeral interpretations with an eye-catching visual counterpart, extending the principle of dissemination using distribution media such as posters, books, wall texts and videos. So the pages of the script of Where what happened to people happened in the head (2018), annotated by the artist and then scanned, are reproduced on ten posters to form the series “Scribbles & Gloss”. She also uses the graphic style of health warnings on cigarette packets. Their typical framed composition, intended to dissuade smokers, which she hijacks with catchy slogans, structures the composition of a set of posters and the two books produced in collaboration with the designer Sabo Day, Pool #1 and Pool #2, which register and arrange the mass of texts collected. This second publication lay at the heart of her show at the UKS in Oslo: still in blister packs, hundreds of copies of the book were piled up on the floor in such a way as to form a platform or stage, around and on which Nora Turato gave her performances, the length of which determined the place’s opening hours. The publication works all at once as archive, autonomous work, set and exhibition. She recently filled the window of the Parisian artist-run space La Plage with a typography overlaid, using a plane effect, on a cigarette box in which are written the words Not available in your country. This spatial arrangement of declarations calls to mind certain installations produced by Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger. This latter, who also started out as a graphic designer in advertising, once declared: “I’m not saying that my art has an effect on other people, but quite simply every day, in Los Angeles where I live, but also in Paris and London, on TV and in the street, I see images and words which strike people, and influence them. Ready-made expressions and opinions, commonplaces, fads. You have to be crazy not to believe in the power of language. We all experience it, day in day out.”4 Through the urgency of her argument and the exploration of many different forms of communication, but less overtly political than Barbara Kruger, Nora Turato still just as much conveys the symptoms of an ambivalent period, in which language oozes through every ‘port’.

1 The infosphere describes a global environment made up of information, as well as all types of data passing through it or stored in it. For the information philosopher Luciano Floridi, the digital upsets the concept of humanity by the same token as the Copernican, Darwinian and Freudian revolutions. According to him, the human being is henceforth above all defined by his ability to create and disseminate information.

See Luciano Floridi, The 4th Revolution: How the Infosphere is Reshaping Human Reality, Oxford University Press, 2014.

2 Kenneth Goldsmith, Uncreative Writing, Managing Language in the Digital Age, Columbia University Press, 2011.

3 www.youtube.com/watch?v=mvFifo4SQH4

4 Jean-Max Colard, “Barbara Kruger, Amour, dégoût et débats d’idées”, Les Inrockuptibles, January 1999.

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Julien Creuzet, Ismaïl Bahri, Flora Moscovici, Eva Barto,

Related articles

Shio Kusaka

by Sarah Matia Pasqualetti

Julian Charrière: Cultural Spaces

by Gabriela Anco

Céleste Richard Zimmermann

by Philippe Szechter