Alun Williams

It is hard to grasp a painting that does not let you grasp it using the usual approaches, which are the relation to modernism and postmodernism, going beyond figuration, and the return of the latter, that is being endlessly postponed, announced, vilified, and foiled. As a rule, to broach a pictorial work, one attempts to make ever more subtle classifications which try to pin the painter down within one category or another, rather in the way that people have always tried to classify animals in order to objectify them and make them subjects for study. So, in painting, there are two great reigns, that of abstraction and that of figuration, which have been violently clashing for more than a century and a half, ever since Manet, Cézanne, and Kandinsky. Alun Williams’s painting seems to thwart this kind of slightly cursory classification, not because his paintings are revolutionary in the sense that they mix figuration with abstraction, which has become a rather commonplace position in the postmodern era, but because they borrow from both these systems, while at the same time pushing back, a little bit further, the boundary of their conflicting coexistence inside the picture.

Everyone is now at liberty to add figuration in the midst of flat tints, and go beyond the edges of the picture: the all-over style has been broadly incorporated in pictorial practices which now play with all these limits, and all these taboos. Greenberg is dead and his orphans are doing quite well, which does not stop us from questioning his prescriptions, because the pictorial principle is still there, whatever we might say and think, subject to the application of colourful substrata with all the possible variations and all the means imaginable, from Niele Toroni’s good old brush no. 50, to Richard Jackson’s whacky painting machines. The spectrum has been radically enlarged in a medium that is indefinitely pushing back its boundaries and endlessly inventing new tools. The subject of painting is no longer painting: the line of thinking pushed to the limit over the generic qualities of the medium that informed painting up until the end of the 1960s is no longer the only fodder for discussion, although it has not totally vanished. In a somewhat enlightening essay on the subject, Dominique Abensour, talking about Richter, shows that he is searching for the boundarybetween a consideration of worldly concerns and the desire to conserve the specific nature of the medium, a narrow avenue between transitiveness and autonomy: for Richter, incidentally, realism is situated more on the side of abstraction than in photographic realism applied to painting.1

Alun Williams’s painting slightly touches all these component elements. In it, narrative rubs shoulders with the most basic abstraction in the form of incongruous splotches, while art history and reflexivity appear in the form of an ongoing revisitation of genres and periods. Let’s take the narrative: with Williams, the narrative is at once instant and impossible, everything is given right away, everything is available for the reading of pictures which respond perfectly to the definition of pictures, setting up situations in which side-by-side figures seem to be the protagonists in stories which it is hard to reconcile. Most of the time, recognizable figures are painted without any displayed virtuosity, in an identical or almost identical reuse of pictorial referents: in his large canvases like Six Fornarinas, on view in the Villa Tamaris, the artist arranges a series of portraits of La Fornarina, the “baker’s daughter” muse whom Raphael plentifully portrayed, before Ingres drew his inspiration and Picasso in his turn participated in this tribute-like reuse, to the point where Williams includes himself in this succession, by way of the famous splotch which is his trademark. The artist does not hesitate to thus “do a cover version of” illustrious pictures like Goya’s Portrait of Charles IV of Spain and his Family in his The Good the Bad and the Ugly, where he replaces the members of the Spanish royal family with his creations, just as he adds “self-portraits” of 20th century painters such as Mark Wallinger, Jeff Koons, Dana Schutz and Warhol, dressed up as Mao, in an impossible merger (we can even make out Jeff Koons doing his business withLaCicciolina in the upper part of the picture, in such deep shadow that she is barely discernible—a rascally wink at the American artist); and, needless to say, the whole family of his splotches, abstracted personifications of historical characters. These latter slip into the compositions, interfering with them, and thus rearranging the history of art in order to tone it down, and take it to an accessible, human dimension, which the mythologization of these great works had put out of reach for us contemporaries. At times you might think you are in Woody Allen’s Zelig, where the ubiquity of the hero shatters, with ineffable wit, the serious nature of great narratives, which, incidentally, we know to be just as subject to falsification… What is there to say? Pure iconoclasm, or a homage to the old masters? Reflexivity well understood and exceeded, or mere observation of a permanent development of style? By bringing together these key figures in the history of painting, William’s gesture is part and parcel of a desire to reassess the portrait, which forms a not inconsiderable part of this history. A straightforward, postmodern way of rewriting history.

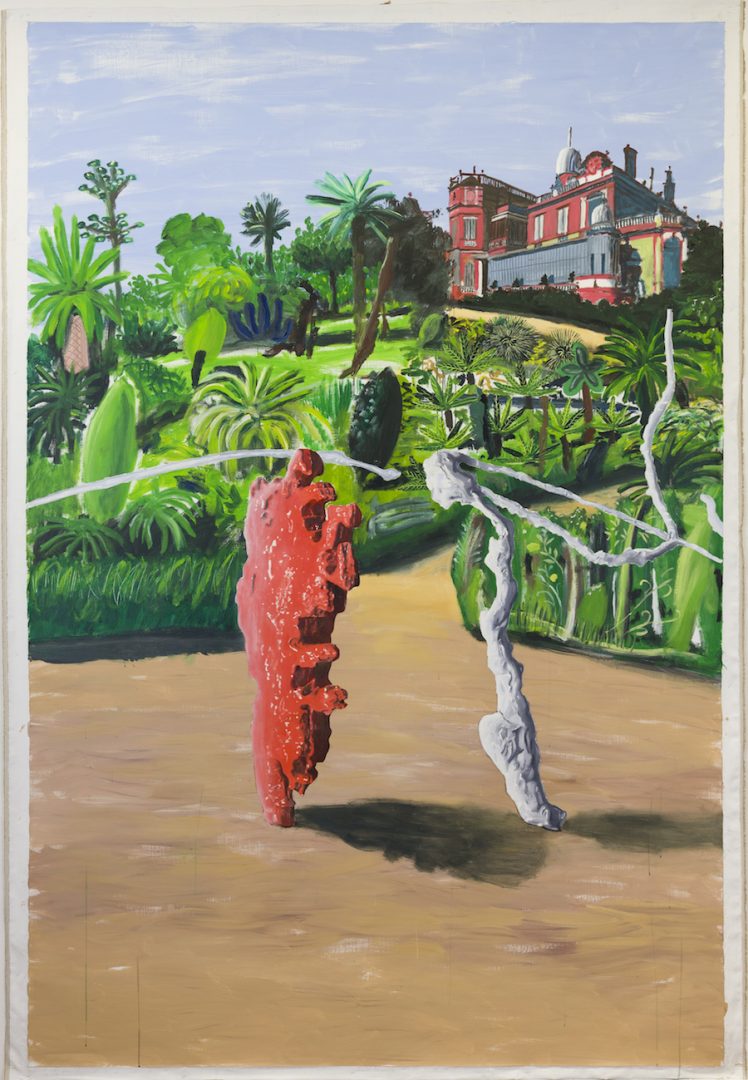

But things become more complicated when one tries to analyze what, for want of any other element of interpretation, we must call splotches. These latter are in fact present in most of Williams’s canvases, where they even manage to occupy the foreground. They merrily find their way into the arrangement of the picture, like characters whose attributes they seem to have, with the shadow in which they are attired making it impossible, de facto, to regard them as simple unpainted areas, or as a purely abstract delimitation inside the picture. A splotch represents the zero degree of abstraction, a sort of pictorial object that is poorly managed in its form, whether it be ‘dripped’ or whether it refers to an assertive desire for non-representation, as a symbol of the specificity of painting (cf. again, Greenberg). But Williams’s splotches are not exactly this, they are both, they represent and they are abstract, they are clues and they are autonomous. These splotches are anything but random forms, they owe nothing to chance. According to the artist, they are actually the traces of the terrestrial passage of these figures, whiffs of their activity, accidental or otherwise, which he unquestioningly attributes to their “author” and which will recur inside a series of pictures and sculptures that will be dedicated to them. Whether thoroughly real or fantasized, these found traces are presented in the pictures in the form of clues, like for example the ink stain from a fountain pen that has leaked, become solidified over the years, and which the artist came upon, abandoned under the desk of a country house-turned-museum… This invisible part of the work is broadly as important as the visible part, the picture, because weeks and even months can pass before the artist is quite sure that the splotch in question does indeed belong to the character he is trying to mark in this way.2 With these splotches, Williams is actually identifying historical characters whom he chooses on the basis of his affinities, and chance. This is the case with Thomas Paine, who is not that well-known in France, even though he played a not inconsiderable role during the revolution of 1789. In North America, he took an active part in the process involving the independence of the thirteen British colonies and, even if he died an isolated death, he has been celebrated ever since for his influence among revolutionaries. So Williams is interested in the character and, in the wake of an investigation that took him from the United Kingdom to the United States, which are the countries—together with France—for which the theoretician become deeply involved, he tracked down and rediscovered a splotch which, for him, can be attributed to Paine, without any hesitation. How did he become so persuaded?3 It does not really matter; the fact is that it is a trace which, for Williams, indisputably identifies the character, and which, from that moment on, would be included in the many pictures devoted to the figure in question. In fact this splash in which this invisible narrative is incarnated is objectively a formal abstraction, while at the same time being the clue to a presence in the world, the clue to a life. A kind of representative abstraction, in a way, so a nice, big oxymoron…

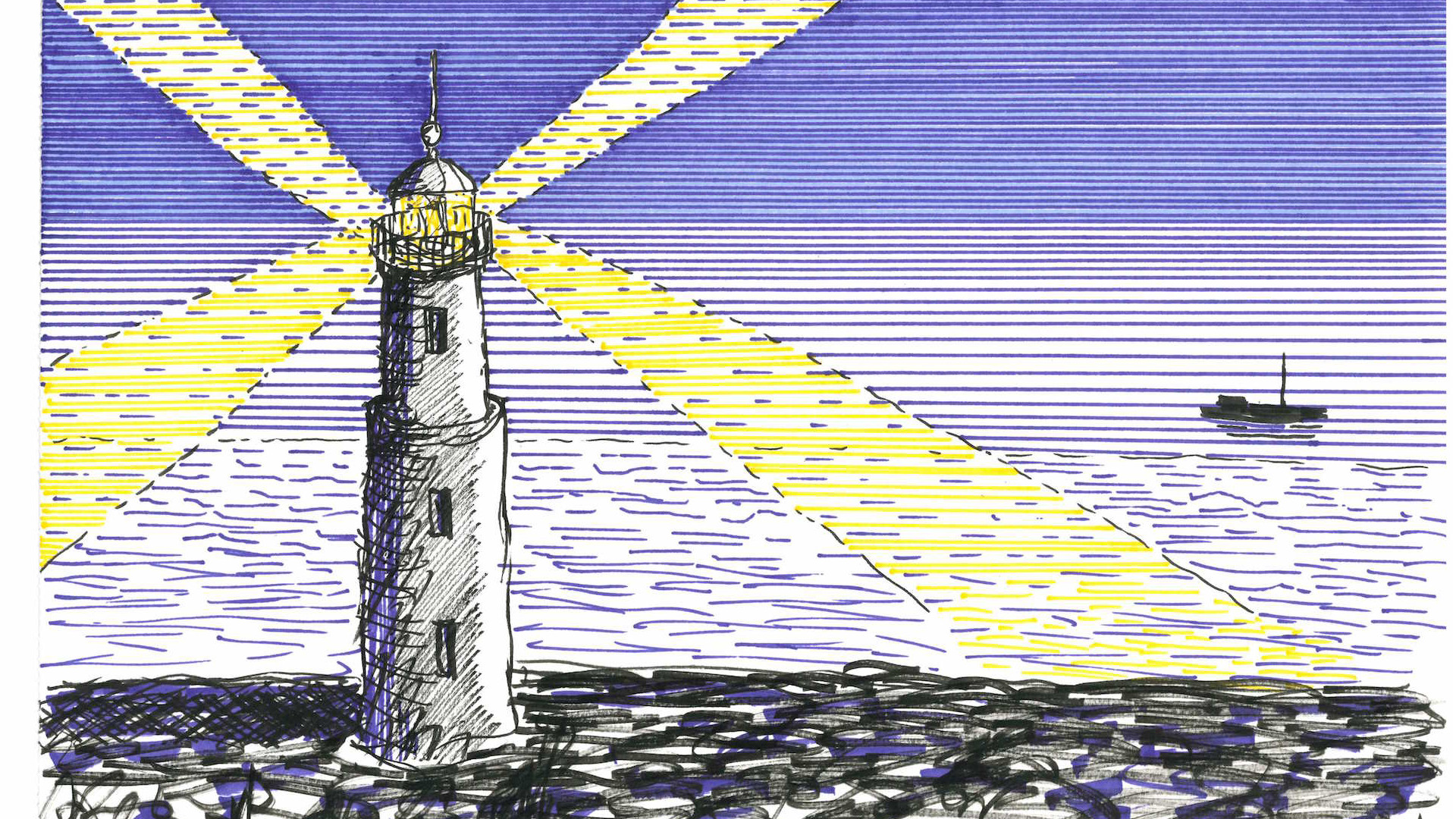

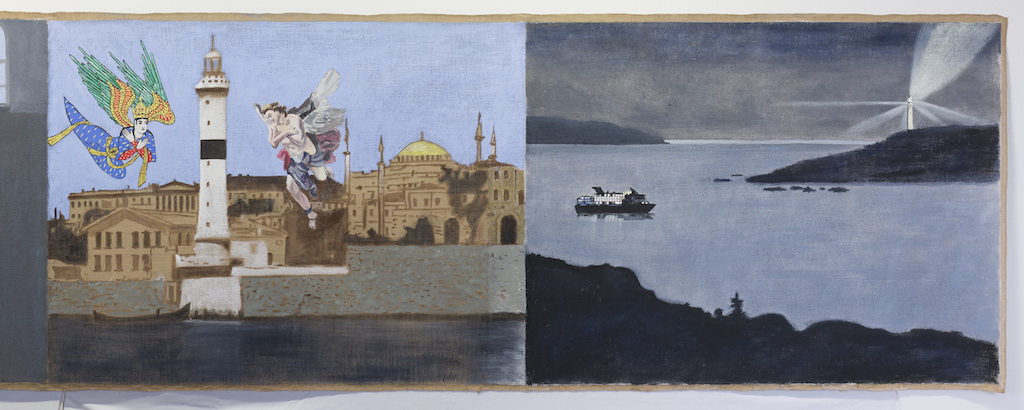

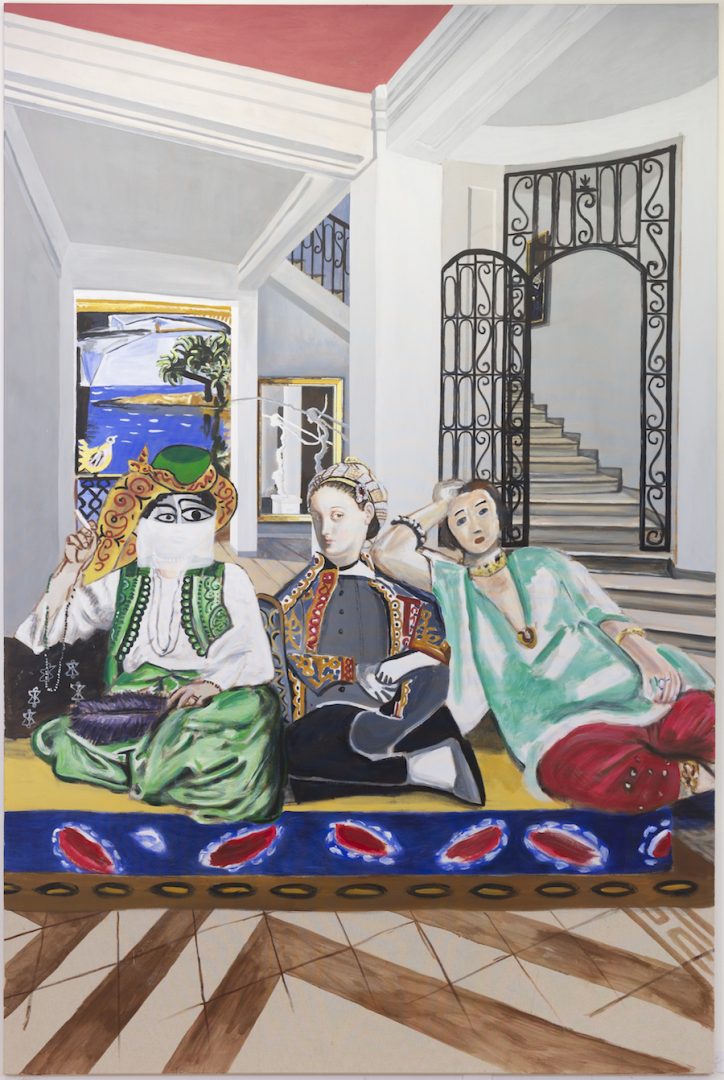

At the Villa Tamaris, Alun Williams, who had not started out with the idea of “tagging” the creator of the said villa, was unable to stop himself doing so when he read the narrative of this person’s life who, during the 19th century, built most of the lighthouses, beacons and buoys which have ever since guided ships crossing the Mediterranean. Lux fecit, the exhibition’s title, makes reference to that prolific builder who lit up the route of navigators and helped to save the lives of hundreds of sailors. Because his life also has novelistic ingredients, it fits perfectly in the logic adopted by the painter, who seems rather to be seeking out extraordinary characters. At La Seyne-sur-Mer, however, Williams has not totally subscribed to his usual method, which is to track down the famous splotch and dedicate the entirety of his pictures to it. The artist did of course find a splotch tallying with that enigmatic Michel Pacha, but he executed a slight shift which means that, through the splotch, which usually hallmarks his manner, this personification has moved towards the motif of the lighthouse, which corresponds to Pacha’s life, but also refers to the growth in trans-Mediterranean trade and the early days of globalization. In one of the pictures on view in the Villa Tamaris (Hommage à la ténacité des femmes: Marie-Rose, Amélie et Élodie Michel), Pacha’s family appears painted in the oriental décor of the mansion he had built for himself in Istanbul, where he spent part of his life—his patronym comes, incidentally, from his ennoblement in Turkey by the Sultan. The picture brings together Pacha’s daughter and two wives, each one depicted in the manner of a clearly identified painter—Picasso, Ingres, Matisse—and, in the background, there appears the Pacha splotch, in a discreet way, embedded in a frame in the sitting room, in a mise en abyme with which the artist is familiar. The most striking work in the show is the series of paintings that the artist produced during his residence, a series of 26 works produced in less than two months. Using the method that he regularly employs, which is to work “in the manner of”, Williams painted nothing less than a medley of canvases whose references range from the end of the 19th century to our current day and age, bringing together the great names of the period, from Picasso to De Staël, and from Turner to Magritte, in the midst of which are incongruously included canvases without any referent, just like the sudden appearance of the representation of a selfie, a contribution and concession to modernity that obliges the painter to espouse the format of the camera, and reverse the reading of the pictures, which, hitherto, was panoramic. The artist thus permits himself a new pirouette which breaks the listing of the great names. But the lighthouse remains the central motif of all these canvases: brought together in a single burlap roll, they summon another iconoclastic aspect which is that of the singleness of a surface on which there is a merry mixture of those masters and their styles, referring to the famous rolls of Chinese painting.

Alun Williams’s paintings make it possible to set up stories that are incompatible and mutually exclusive, like science-fiction scenarios in which characters hailing from parallel worlds and times rub shoulders in unthinkable situations: it is the magic of painting that makes it possible to give plausibility to these heterogeneous factors when the other arts of the image, like film and video, fail to immediately reflect the depth of the cultural and historical challenges referred to. As the critic and artist David Humphrey puts it: “Williams’ paintings conjure unconsidered possibilities and illuminate obscure areas of the collective imagination”.”4 So it is no coincidence that the character of Jules Verne reappears in one of the latest paintings in the exhibition (Aux visionnaires modernes: Jules Verne et Michel Pacha (Tamaris, circa 1888), causing him to meet that other pathfinder in the darkness, called Michel Pacha. If official history has never confirmed any such encounter, it was up to an artist with the power to adapt to factual truths to organize that imaginary meeting between two creatures who both illuminated the burgeoning 20th century…

1 “Contradiction has always been a driving force in Richter’s approach. In his painted photographs, he is not content to transgress the separation between abstraction and figuration, but rather executes a reversal: his works reveal both the figurative capacities of abstract painting and the abstract dimension of photography”. Dominique Abensour, “Peinture et photographie” in La Peinture, Ecole Supérieure des Beaux-arts de Bretagne, edited by Christophe Viart, 2019, p. 85.

2 In the monographic catalogue devoted to him (Lest, Manuela éditions, 2019), Alun Williams returns at length to the identifying conditions of the owners of these splotches. This publication involves the Jules Verne-like narrative of the journey—and he is an ardent admirer of Jules Verne, whose trace he also discovered)—more than the classical exercise of defining an art praxis, which is, moreover, completely absent from the catalogue.

3 “Soon after arriving we were all strolling down John Adams Way, looking once again in every nook and cranny for the elusive trace, usually, preferably, a completely accidental paint mark that could enthusiastically be recognised as being perfectly emblematic of the character in question!”, Alun Williams, Lest, op. cit, p. 27.

4 David Humphrey, brochure for the exhibition “Lux fecit” at Villa Tamaris, Toulon, 17.11.2019 – 9.02.2020.

Image on top: Alun Williams, Phare#39 (4 faisceaux jaunes et un bateau de pêche), 2019. Ink on paper.

- From the issue: 93

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Jack Warne, Ben Thorp Brown, Mircea Cantor, David Horvitz, Olivier Mosset, Jean-Baptiste Sauvage,

Related articles

Gregory Sholette

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Vera Kox

by Mya Finbow

Fabrice Hyber

by Philippe Szechter