Chantal Akerman

Chantal Akerman’s Truths

Jeu de Paume, Paris

23 September 2024 — 19 January 2025

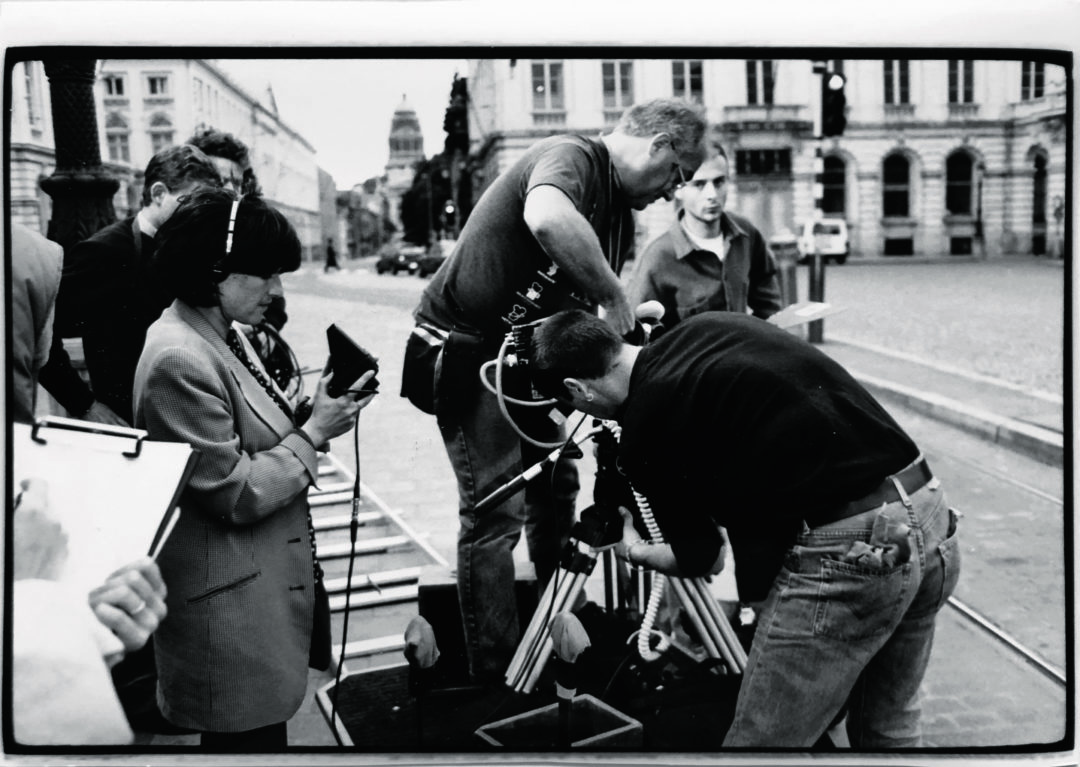

In memory of influential contemporary filmmaker Chantal Akerman (b. 1950 Etterbeek, Belgium, d. 2015, Paris), the Jeu de Paume has honored the Belgian artist’s œuvre a decade after her death by suicide. Entitled “Traveling”, the exhibition—which was developed in partnership with the Palais des Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles, the Fondation Chantal Akerman, and the cinémathèque royale de Belgique—establishes links between Akerman’s films, installations and text-based work (synopsis, voice overs, documentation, manuscripts) by opening up its archives. The exhibition is organized chronologically, beginning with the artist’s activities in Brussels, to on-set activities at the age of 18 during early forays in filmmaking, leading to Mexico by way of Paris and New York and the discovery of experimental cinema. “Traveling” explores the cartography of an œuvre which delves into notions of the female body as site of eternal struggle via the act of writing.

Through Language

Everything about Chantal Akerman has already been written. The fact that she was the first filmmaker to be exhibited in a museum context has already been established; this in fact is what confers on Akerman the status of artist. “Traveling” is nonetheless the exhibition of a writer’s work. Akerman’s words are present beginning with the introductory text, the exhibition’s language lays out the stakes through wall texts, reading tables with armchairs, explanatory texts are also displayed on the walls—not as museological paragon but rather as commentary. Akerman’s explanations give writing a central status within her œuvre. For her, fiction has a pivotal role within reality. As Marguerite Duras stated in response to criticism of changes made during the screen adaptation of The Sea Wall, “if it’s been written, then it must be true!” Chantal Akerman’s voice can be heard clearly in “Traveling;” here, film exists through the editing process.

Why an Akerman exhibition in 2024? Through which lens do we see her œuvre today? In the 1960s, Marshall McLuhan observed that, “We shape our tools, and thereafter our tools shape us.” The exhibition can also be interpreted through the ten years gap since the death of the artist: the rise of toxic masculinity on socials, in the media in general and in politics, the diminishing rights of women in a number of countries. Revisiting Akerman today means restating the obvious in contemporary society. Through text, the artist emancipates herself through writing from the normative and oppressive values of homemaking which has been assigned to women by default.

I Never Made It Out of My Night

The exhibition opens with the artist’s intent: her presence questions ours. Akerman speaks to us, she addresses us directly. The first video installation, Seated Woman Immediately After Having Killed reprises the final sequence of Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) by multiplying it, with Akerman within the frame. From the very beginning, the end is here. A projected excerpt of The Beloved Child, or I Play at Being a Married Woman is directly opposite, and shows a nude woman standing in front of a mirror on a pedestal. The subject is calm. In the second space, FROM THE EAST: Bordering on Fiction is about nomadism and cacophony. Here, Eastern European landscapes are seen, each with its own language. We travel across them, just as a life is crossed through.

In Akerman’s first short film, Blow Up My Town (1968), an isolated woman (played by the filmmaker herself) resists a domestic world where nothing works as it should (the elevator is broken, water boils over in the pot…). The film is clearly not headed toward a happy ending. The character, who has been sent to the kitchen (as a setting, which creates a context) could, with her robotic choreography, just as well feature in a Jacques Tati film. Similarly, the artist’s career would last another forty films, and end at the same time as her life.

“Traveling” raises the question of subjectivity through writing and filmed voice, it is about gazes, about journeys. Recurring themes throughout Akerman’s work—such as isolation, loss or exile provide a subtext for the exhibition. She once noted that she often discovered the intention of her “subjectless” films only once they had been completed. Is the documentary the only form capable of achieving enough distance in order to speak of that which cannot be spoken of? For Akerman, whose films are centred on her mother Natalia, a Holocaust survivor, the protagonist is truth. “I’m sometimes under the impression that I’m speaking for my mother, my sister, that I’m saying things they wouldn’t be able to say. In a way, my films and I exist to fill that role. The words my mother uses when talking about my work are always devastating. She’s always way ahead of my thought process, she sees things that I really don’t understand until after having finished a project. In One Day Pina (Bausch) Asked, there’s a pretty cruel scene, where a woman’s face is disfigured. She said, “You see, that’s how we felt in the camps. We were subjected to this.” Although not officially autobiographical, the stories I tell are related to the lives of the people I’m surrounded with and who have lived through certain things. One has been almost unable to speak, and the other speaks about it almost without noticing.” Perhaps cacophony is this as well—voices covering over the silence we expect to encounter when entering an exhibition space.

A Document as Opposed to Monument

The Jeu de Paume has chosen to situate the entire exhibition around a central archive which serves as reading room for visitors. In the space, screenplays, handwritten script annotations, notes and other preparatory drafts from films such as Jeanne Dielman, Golden Eighties, Meetings With Anna, A Couch in New York are on the walls and in the binders, available for consultation. Photographic prints, press clippings, daily rushes and letters are also available for visitors to peruse in what can be considered an extended exhibition, an exhibition with use value. It is through this room that the visitor enters into the space of Akerman’s writing, by engaging corporeally with it. According to Barthes, the body of the reader is affected by the text during the act of reading, the reader is shaken to their core. “Traveling” draws attention to the communal existence a text provides us with, to the effects this alterity has on our bodies; or, to quote Jean-Luc Nancy, otherwise leads us to think of the body as a form of openness to the Other.

The Third Text and the Female Gaze

The figure of the mother is present throughout Akerman’s œuvre. The artist also mines female representation in general: as flesh, a domesticated body (by the patriarchy, industry, film, and art). Akerman’s films do not create a Theatre of the Oppressed, however. Whether filmic, photographic or written, the works are a type of movement. In Hitchcock’s Vertigo, which the filmmaker watched in her formative years, the principal female character is reiterated, becomes doubled (Maddie becomes Judy). The truth is revealed much later, as the storyline progresses (when the woman kills herself a “second” time). The search for identity is a recurring theme in Akerman’s œuvre, in equal measure to the objectification of bodies as well as its reproducibility.

Cinema as a whole is inscribed in normative codes established in Hollywood over a century ago. The male gaze was transactional in nature: it perpetuated power dynamics which shaped society in order to ensure the success of its films within the system which produced it. Perhaps we could refer to a third text with regard to the archive, in the same way we refer to third places (common), third images (collected), or third spaces (places where individuality is called into question)? French landscape architect Gilles Clément refers to the notion of a third landscape, an “abandoned” which avoids capitalistic productivity standards. The exhibition revives Chantal Akerman’s repeated attempts at emancipation—it is within the realm of thirds that we are able to escape societal injunctions.

Endgame

The artist would make her last film in 2014, which corresponded with the death of her mother. No Home Movie was “about the world turning which my mother cannot see,” just before her passing. Her final piece was shown at the 2015 Venice Biennale, curated by Enwezor in the prophetic installation Now. According to Jankélévitch, a philosopher for whom the present is more than just an “almost already past”, adding that we should “not miss out on our early spring,” encouraging a permanent improvisational approach toward life. This dizziness is what emerges from this late-career work. In the final two exhibition spaces are a projection of A Voice in the Desert (2002) and the installation Autobiography/Selfportrait in Progress (1998), which was made by piecing together several films and a book, A Family in Brussels (1998): an attempt at a self-portrait in the form of final punctuation.

By creating a dialogue between techniques of objectivization which have been subverted and representational systems which subject and enclose (the film medium as political tool), Akerman has created a room of her own for herself, made up of montage and text, an infinitely open œuvre. Agnès Varda said that the ultimate feminist act, for a woman under observation, is to say “I observe, too.” “Traveling” is an invitation to expand upon the screenplays of Chantal Akerman through the writing of an existence of one’s own.

Head image : Chantal Akerman, Photogramme du film / Frame from the film Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, 1975. © Fondation Chantal Akerman / Capricci. © Adagp, Paris, 2024.

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Carole Douillard,

Related articles

Biennale Son

by Guillaume Lasserre

Lou Masduraud

by Vanessa Morisset

Bharti Kher

by Sarah Matia Pasqualetti