Christopher Kulendran Thomas

Christopher Kulendran Thomas, New Eelam, 2016.

9th Berlin Biennale, featuring artworks by Asela Gunasekara,

Nuwan Nalaka, Muvindu Binoy (purchased from Artspace Sri Lanka) and furniture by NEW TENDENCY et e15.

Some would have certainly passed by, would have certainly passed through without even noticing it: the small lounge with a comfy sofa, thick carpet, paintings on the walls and bibelots without too much ostentation, relatively standardized international chic style,

was in fact Christopher Kulendran Thomas’installation for the last Berlin Biennale. There, a flat screen TV was broadcasting what looked like a docutainment: archive footage from news, science and history documentaries, 3D render and retouched images altogether put the setting up of the Tamil Eelam state in Sri Lanka and the later creation of the retail giant Amazon in perspective with the history of humanity and sedentary lifestyle, establishing extremely questionable links between marxism and global capitalism, even suggesting the abolition of their antagonism. The controversy then dissolved into a sort of promotional film for a new real estate offer, a new lifestyle, a new society, a new life.

Overpassing the immediate consumption of artworks into which biennales tend to lead their visitors, these latter passing through them very quickly just to glance at the latest trends, Christopher Kulendran Thomas is stepping out of this model with a long-term strategy that uses the art space as a test space for a project which takes place in a wider economic reality than the mere contemporary art market, while including it in his own work as a material. We discussed with him his understanding of the artworld as a space for efficiency.

I’d like to start this discussion coming back to the basics of your work, that is to say your ongoing project (since 2013) When Platitudes Become Form, for which you purchase contemporary artworks in galleries in Sri Lanka and “reconfigure them for the international (Western) contemporary art market”. You’ve already said a lot about that project over the last years, but I’d like to hear you more precisely on the way you operate the translation between the two meanings of the term contemporary, and especially on a visual level.

Is the manner you “re-configure” these artworks for Western eyes and Western markets purely empirical, that is to say based on the aesthetics of the artworks that sell well?

Well, by way of historical context: the artists whose work I buy – and then use as my materials, as components in my work – have become successful in the new regional market for contemporary art that has developed in Sri Lanka over the last five or six years following the brutal war crimes that ended the Sri Lankan civil war in 2009. The economic liberalisation that followed what many people call a genocide there brought with it the first generation of Western-style commercial galleries that are creating a new regional market for what is now called there contemporary art.

For example, in this work from a few years ago, I bought this painting by a young artist called Pramith Geekiyanage who had just started showing with the most influential new commercial gallery in Colombo. In this case, I simply added these vertical blinds. The translation is always based on the recurring memes that are in circulation amongst my peers in the context into which I’m working. But the original works that I’m purchasing in Sri Lanka are also the product of a slower flow of memes – from the Western art historical canon to Sri Lankan contemporary.

Christopher Kulendran Thomas, When Platitudes Become Form, 2013. Wood, acrylic, ‘Ganesh XII’ by Prageeth Manohansa (purchased from Saskia Fernando Gallery, Colombo, Sri Lanka) and Nike Pro Combat compression shirt.

The term ‘contemporary’ has been used throughout at least the last half-century to refer to art being made at the time. But I think it means something else now, in that I think Contemporary Art has become a genre – a historically specific genre which came about at a time of globalising economic liberalisation. And what ‘contemporary’ means now in Sri Lanka is perhaps what it actually means anywhere: it refers to a genre that is at least derived from the Western canon. So the translation in the work I’m doing is from what counts as contemporary in one market/context into what counts as contemporary in another – which is of course also the difference between where my parents are from and where I am now.

Adding economic value to an object by camouflaging it is a way of subverting not only the parameters of the global art market but also the essence of visual art, which is traditionally based on a one-to-one relation between the object and the viewer. In doing so, you act as a third party troubling centuries of aesthetic certainties. Does that mean that, according to you, this idea of art as a personal aesthetic relationship to an object is absolutely contingent?

Christopher Kulendran Thomas, When Platitudes Become Form, 2013.

Wood, acrylic, ‘Lion’ by Prageeth Manohansa (purchased from Saskia Fernando Gallery, Colombo, Sri Lanka) and Nike New Distance singlet.

I think that’s a really good way of putting it. It seems to me that this art historical paradigm – by which the viewer’s interpretation completes the artwork – may be unravelling in an age of increasing networked connectedness; an era in which it seems more and more relevant to understand art as being completed by circulation rather than spectatorship. Through the work that I’ve been doing, I’ve come to understand spectatorship as simply part of the process rather than the purpose of the work. But the trajectory of the process is what’s become most interesting to me: the more that the work I’m doing is taken up, the more I buy of these original artworks from Sri Lanka’s most promising young artists. For example, in some of the works that I started doing in 2013, drawings by the artist Prageeth Manohansa were purchased from Saskia Fernando Gallery in Colombo and ‘re-mounted’, you could say, on stretched Nike t-shirts (many of which are also made in Sri Lanka). So that artist is becoming a big deal in Sri Lanka but his work is also circulating internationally as materials in my work and in collections and museums where his work is not circulating on its own terms.

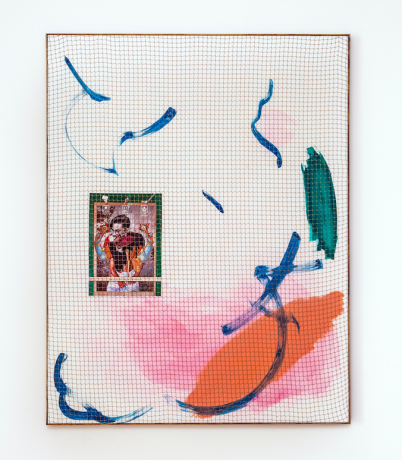

Christopher Kulendran Thomas, When Platitudes Become Form, 2016. Acrylic on canvas, wooden frame, net and ‘Humans are Spiritualy Confused’ (2014) by Muvindu Binoy (purchased from Art Space, Sri Lanka), 160 x 120 x 4 cm.

But rather than contemporary art’s usual projection of itself as a platform of equality (at least in theory), the more this work unfolds, the more it seems to be intensifying the structural assymetry between its materials. And just like the assymetry between my family’s origins and my current context, this is constituted through complex ecologies of globalisation – of military and economic violence. In Sri Lanka, the United Nation’s conception of human rights gave cover for the international community to avoid intervening to prevent what is coming to be more widely recognised now as a genocide. And that violence continues through ‘soft’ (economic) ethnic cleansing, with the spoils of new-found prosperity (like contemporary art) becoming a sort of retrospective justification for the violence which that prosperity is based on. In a way, the liberal humanist conception of universal rights could be seen as part of the problem. And I think it’s contemporary art’s aesthetic version of that juridical problem – what Boris Groys calls “equal aesthetic rights” – that the trajectory of this work confronts. Curator Victoria Ivanova introduced me to the idea of ‘posthuman rights’. And thinking about what that could be is perhaps a good way into the ethics of this work and the problems it comes from. And that’s the thing: it’s a way of having the problem rather than pointing to it from a safe critical distance. I think it’s the trajectory of the work as it unfolds that does the actual ‘work’ of the work. But this is a volatile trajectory. For example, Prageeth Manohansa’s prices have been increasing fast and if his career really takes off internationally then there could come a point when the components of my work might be worth more than the work itself. So it could economically rip itself apart.

But also it’s hard to calculate the consequences that the trajectory of this work could have on the emerging market for Sri Lankan contemporary art. For example, as the circulationary discrepancy between my work and the artworks I use as my materials has become increasingly extreme, one of the important galleries in Sri Lanka has taken on a new artist who is being billed as Sri Lanka’s ‘post-Internet’ artist. So buying his work has meant flipping the aesthetics of my work to make these abstract paintings on which to mount his digital collages, all of which is then wrapped in fishing net.

Christopher Kulendran Thomas, New Eelam, 2016. 9th Berlin Biennale, with artworks by Asela Gunasekara, Nuwan Nalaka, Muvindu Binoy (purchased from Art Space Sri Lanka). Photo : Laura Fiorio.

But you could see this type of painting that you’re doing as being very much in line with a return to more expressive ways of making art that has now become popular amongst your peers.

Absolutely; and I think that’s why I’m able to do it. But perhaps what “expressive” means is, in itself, pretty interesting. Maybe what’s being expressed is not a ‘self’ as much as a circulation of memes through which is co-constituted what it looks like and feels like to be human and to express oneself, like a sort of synthetic DNA. I guess my work operates a kind of machinic translation across these flows of bio-cultural data.

So, to push this reflection further — and here I’m anticipating a bit ahead of our time —could what you referred to as the “increasing networked connectedness” we’re facing be announcing the end of the autonomous individual subjectivity as we know it?

It seems to me that perhaps one of the most pervasive myths of our time is the idea that humans are categorically distinct to everything that’s not human; and the ecologically devastating consequences of these dillusions of superiority are now more widely recognised, giving way to an understanding of reality as not necessarily revolving around us. Today’s most ubiquitous digital platforms could be understood as sites of intersection between human and non-human materiality. And I think it’s unlikely that future generations of our species will understand the limits of their bodies in the same way we might have before our total immersion in networked technology. We are the medium more than the medium is for us. And I think art has to evolve in line with this shift in understanding.

Of course art has always been produced by (and helped produce) its contiguous reality. But art’s structural operations – for example on the front line of globalisation, prototyping immaterial labour, as part of the processes of gentrification by which cities around the world are remade – all these structural operations, at which art is actually incredibly effective, are typically disavowed in the era of contemporary art in favour of discussing art’s consequences primarily in terms of the viewer’s interpretation; as if reality revolves around our interpretation of it.

Christopher Kulendran Thomas, New Eelam, 2016. 9th Berlin Biennale, and ‘Skin Deep’ by Asela Gunasekara (purchased from Artspace, Sri Lanka). Photo : Laura Fiorio.

And, as it’s tempting when reading you considering “spectatorship as simply part of the process rather than the purpose of the work”, what would be the purpose of the work?

In Sri Lanka, over the last few years, you have this accelerated microcosm in which to see these structural operations play out quite vividly as a product of brutal violence and as a function of economic liberalisation. So I started doing this work to negotiate my distance from where my family is from and to come to terms with what I found difficult to face about that distance and what was going on in Sri Lanka at the time. But doing it has forced me to confront much simpler issues – about fitting in; or maybe wanting to fit in but not even believing in what I want to fit in with. Perhaps that’s a classic second generation immigrant story.

I guess for me the most valuable thing about doing art is to be able to externalise these inner conflicts or contradictions; and then by putting these problems out there and negotiating them I end up coming to a more sophisticated understanding about what’s at stake. I think that’s the clearest thing I can say about why I do art. But on a less personal scale, I think the work I’ve been doing has been a way of engaging what art actually does in the world. And that’s led me to a new phase of this work which is more about doing something constructive with art’s structural operations.

Christopher Kulendran Thomas, New Eelam, 2016. 9th Berlin Biennale. Graphic design: Manuel Bürger & Jan Gieseking, images: Joseph Kadow. Photo : Laura Fiorio.

New Eelam, yes, a long-term project, the branding for which I noticed was introduced subtly in the “Co-workers” exhibition at the Paris Musée d’Art moderne (Oct. 2015-Jan. 2016) and then launched more fully as part of the 9th Berlin Biennale and the 11th Gwangju Biennale, and of which When Platitudes Become Form is now part and parcel. The statement for it says it is “an alternative proposal for how a new economic system could evolve, without friction, out of the present one—through the luxury of communalism rather than private property” by way of a streaming system of housing to enable what the promotional film introduces as a “more liquid form of citizenship beyond borders”.

Could you specify what such a business project has to do with the art world?

I think art has always been good at prototyping new lifestyle formats, new ways of living. Loft living is an obvious example of something that the art world did more than half a century ago and that has since become a mainstream lifestyle aspiration. But the more jobs are automated, the more that what artists do becomes a way of prototyping the future of immaterial labour for a post-work economy, while the home (rather than the factory or office) becomes a primary site of production. So the company that I’m starting with colleagues is developing a flexible global housing subscription to take collective ownership of that means of production – the home. A flat-rate monthly subscription will give global citizens continual access to high-quality apartments around the world so you can move around freely between cities. And each of New Eelam’s subscribers will accumulate shares in the revolving portfolio of properties. So over time the growing value of each citizen’s stake could increasingly subside the cost of their subscription.

It’s an alternative to the defeated political strategy that was crushed so disastrously in Sri Lanka. Rather than a military revolution to establish a self-governing state, we want to make the home of the future part of a distributed network rather than part of a territorially bounded nation, by growing a new economic model instead of opposing the present one. We’re initially introducing this venture in the art field and, in collaboration with curator Annika Kuhlman, we’re interested in how the space of art could be used to do commercial or political communication with more depth and complexity than we could do in other contexts. So in making our current exhibitions, we’ve been asking ourselves: how could a brand communicate as an artist?

When I met Annika Kuhlman, she told me that New Eelam “is not something that looks like a start up, it is a start up. It is what it presents, it doesn’t represent”.

For the Gwangju Biennale, you developed images for New Eelam’s ad campaign, turning the space devoted to your solo show into a 360° branding space. So, could you say this merging of art and business you operate and the way you just described it saying your idea was “growing a new economic model instead of opposing the present one”, is an infiltration strategy set up as a self-willed choice or rather imposed by the economic system itself? Otherwise put, do you agree with the way Metahaven put it when writing: “Capitalist realism functions as a frameset which forces its political opponents to ‘speak the same language’. […] any alternative (by the oppressed) must first be rendered in the language and protocol of the oppressor”?1

I do entirely agree with that but I also think that real long-term political transformation is more likely to be achieved by making something that works better (by making something that people want) than by requiring a moral choice. So we want to enable greater freedom and flexibility through collective ownership than would be possible through individually owned private property, making housing function more like an information good. And for that to work, it need not feel like a political revolution; it just has to work better than what it’s an alternative to – which is real estate markets that concretise a fundamental antagonism between renting and owning.

Christopher Kulendran Thomas, advertising campaign for New Eelam, 2016. Graphic design and rendering: Manuel Bürger & Jan Gieseking, image: Joseph Kadow.

Precisely, you act in the wake of this awareness you evoke as part of your reflection, which is to envision “today’s most ubiquitous technology platforms — like Google, Amazon, Facebook or Apple — as transnational states”. Would you say you could envision New Eelam as a post-capitalist counterpoint of those platforms while using a somewhat similar conception?

And, as every utopia has proven to have a dark side, what would New Eelam’s be?

Despite the current resurgence of nationalist politics in certain parts of the world, more long-term I think the nation state is an organisational form that will become less and less significant. Meanwhile, as you say, global platforms are beginning to act like nation states, whilst actual governments (like Estonia’s) are understanding themselves as startups. Within this transnational extra-state landscape, my colleagues and I see the potential for New Eelam’s collective ownership model to potentially out-compete profit-making capitalist economies beyond national borders. But I don’t think we see this as a utopian endeavour because we don’t have a defined, idealised place to get to; rather the venture is grounded in a re-wiring of existing processes that can’t be imposed on anyone. So we can only be successful if we can give people what they want. I see this as a sort of proximal sci-fi, in that it proposes an alternate reality that’s very close to the reality that we would recognise but with a crucial part of its logic rewired, specifically the type of property relations that we are attempting to reformulate. The artistic excitement for me is in translating, over time, this imaginative proposition into a potentially transformational reality.

1 Metahaven, Can jokes bring down governments?, Strelka Press, 2013, p.14.

- From the issue: 79

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Paolo Cirio, Kate Crawford | Trevor Paglen, Sylvain Darrifourcq, Computer Grrrls, Franz Wanner,

Related articles

Shio Kusaka

by Sarah Matia Pasqualetti

Julian Charrière: Cultural Spaces

by Gabriela Anco

Céline Poulin

by Andréanne Béguin