Fabrice Hyber

Air-conditioning the world

Born in 1961, Fabrice Hyber, an internationally renowned artist from the Vendée region, is being welcomed like a messiah at the Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain des Sables-d’Olonne (MASC) and the Abbaye Saint-Jean d’Orbestier. Conceived in close collaboration with exhibition curator Philippe Piguet, this summer exhibition, ‘La Fabrique du climat’, marks the end of the sixtieth anniversary of the MASC before it closes for restoration and expansion by architect Jean-Michel Wilmotte. Highlighting the artist’s pioneering interest in the various issues surrounding climate change, this event explores a topical theme that highlights the continuity of his approach, which began in the late 1980s at, when he was planting a forest on his family’s land. Here, the artist continues to build an artistic and cultural project that he calls La Vallée¹, conceived as a place of learning, experimentation and transmission of knowledge linked to ecology.

Trained at the Fine Arts School in Nantes and noticed at a very young age, Fabrice Hyber soon found himself supported – to name but a few – by gallery owner Didier Larnac, art critic Pierre Giquel and curator Henri-Claude Cousseau. His early works have become emblematic, including Un Mètre carré de rouge à lèvres (1981), L’Homme de Bessine (1989), his self-portrait Traduction (1991), which is the largest bar of soap in the world in the Guinness Book of Records, and Eau d’or, Eau dort, ODOR, a television studio created for the French Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1997, which, thanks to the award of the Lion d’Or, established the artist internationally. The ‘La Fabrique du climat’ exhibition is therefore an opportunity to take a fresh look at a body of work that, because of its prodigality, exuberance and entrepreneurial aspects, was able to destabilise an art world still attached to the aesthetic values of the past. It’s also an opportunity to explore related issues, such as landscape and the sciences in general – mathematics, biology, geology – which the artist tackles both in his pictorial practice and in his sculptural creations, such as his P.O.F.² (Prototypes d’Objets en Fonctionnement), poetic objects that invite singular and collective appropriations by spectators.

The introduction to this exhibition allows us to appreciate the artist’s provocative spirit, with two youthful drawings dated 1982 with satirical titles: L’Ombre du Roi-Soleil, a ‘granvillesque’ caricature depicting a paunchy character with a ‘potato’ nose whom the sun metamorphoses into a woman made visible by his cast shadow, or Années sombres du règne de Louis XIV (after Quicherat)³. This homage to a mischievous sun, creator of all things, is also found in the painting Cible jaune (1984), whose centre, occupied by a bedside lamp, extends in a linear concentric form, with a strong kineticism, radiating out into the frame to suggest infinity. With La plus belle d’Europe (1985), an eroticised postcard painting in the vein of the free figuration of the 1980s, concerns emerge about the influence of the weather on bodies. Depicted in the bay of Les Sables-d’Olonne, a pin-up – or rather a Venus – painted in reserve floats on the sea. But the artist ingeniously inscribes ‘ It’s raining in Les Sables-d’Olonne ’ vertically in charcoal, as if to counterbalance the fact that this nymph is basking in the sun. Fabrice Hyber ironically informs us that this figure is none other than his mother, which some might interpret as a homophone or tautological game: mother/sea. Meteorological preoccupations become even more evident in his painting Pluie II (1984), in which it is not so much bad weather that he seeks to represent as rain itself. The artist’s comments give us a better understanding of his creative process. Through a series of speculative reasonings and attitude sequences, Fabrice Hyber says that he has psychically metamorphosed into rain, and consequently discovered the spiral movement it describes as it falls. This painting, like many others, turns out to be a recording surface for thought and gesture, linked to the artist’s climatic state, and not a preconceived, premeditated image. This phenomenon was highlighted by the naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, the precursor of ecology, who defined climate as a ‘set of atmospheric variables that affect our organs in a sensitive manner […], the morale of man and the harmony of his faculties’⁴.

The scientific development of Fabrice Hyber’s work becomes more apparent in De fil en aiguille (1988), which sheds further light on his cultural, scientific and artistic influences. This painting plunges us into a scientific universe akin to that of a chemist grappling with experiments, setting in motion indeterminate fluids passing through test tubes, glass coils, funnels and flasks. Although the painting is an attempt by the artist to represent the way he thinks, it is more akin to a fanciful illustration of Kjeldahl’s method for determining the nitrogen content of a sample. We can’t help but see in it a reference to Marcel Duchamp’s The Bride. Later, meteorological phenomena came to occupy a prominent place in many of his paintings, such as Météo tous les temps (2009), in which suns, clouds, rain, rainbows, thunderstorms and snow accumulate. In the game of partitions in Géologie météo, questions of climate and landscape emerge. The ‘Hyberian’ plastic vocabulary is asserted here, with pictorial surfaces in white spirit-washed colours, typical of the topography of the Vendée, invaded by mathematical signs + and -, asterisks and charcoal arrows. Sibylline phrases like ‘ the climate/weather replaces the landscape “ are scattered alongside ” constructing the landscape ’ and ‘ signs revealed in climatic behaviour ’. The artist places us in front of a painting that evokes that of a university lecturer whose oral demonstration has been left behind to make way for fragments of a meteorology lecture. The viewer is invited to fill in the gaps in the reasoning. Mini-podcasts on the artist’s website provide access to a light-hearted commentary by the master himself on his paintings, as if they could not stand on their own. This didactic effort does not entirely dispel our questions. Fabrice Hyber arouses our desire to resolve them, even as he asserts that his paintings are part of his desire to know the world for its own sake, while ultimately leading us to re-evaluate and enrich our knowledge, including our scientific knowledge.

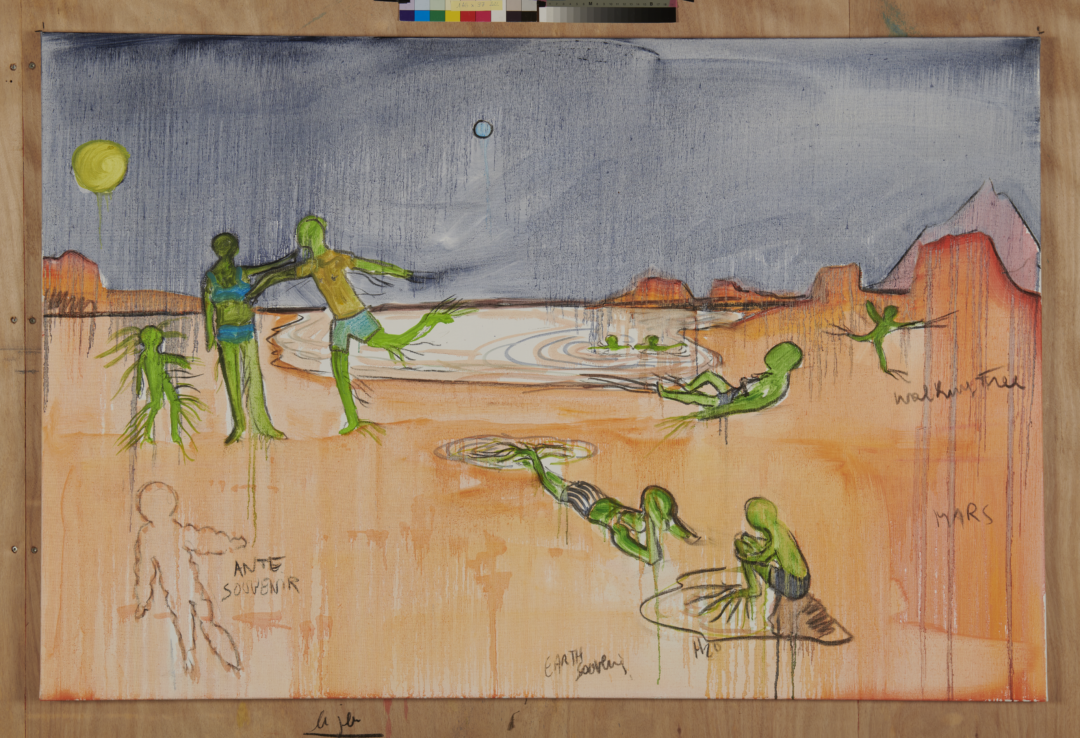

Since the early 2000s, Fabrice Hyber’s artistic concerns about the consequences of global warming, as highlighted by the IPCC, have become even more pressing. There is also the issue of landscape, a term he uses to describe both his paintings and the forest he planted on his family’s farm. We need to go back to the artist’s roots, to the land where he was born, the countryside, his parents’ land, to his interest in the plant world, to the seeds that are beginning to germinate. We are quick to see Fabrice Hyber as a budding botanist, following in the footsteps of the poet-botanist J. W. von Goethe, observing tree seeds as they germinate⁵. But this was not the scientific path he took, despite his interest in the mathematics of Poincaré and the chaos theorist Otto E. Rössler. Rössler. By entering the field of art, he sought to make visible not only what he felt and perceived about the ecological damage caused by the re-parcelling of agricultural plots in the Vendée bocage after 1968, but also other possibilities by flirting with science fiction. Her paintings, which are studio-based – or rather, the artist uses studios according to the season – shatter the idea of the ‘natural’ landscape, an archaic concept that some people are keen to brandish in the name of preserving it, conveyed by the cultural and artistic model inherited from the nineteenth century. With Muroute (2006), depicting a besieged citadel, a sort of hybrid of Fort Boyard and the Fiat Lingotto factory, with RISK (2006), a maritime shipwreck of migrants represented as giant pushahs, or with Martiens à la plage (2022), an extraterrestrial territory populated by green men, Fabrice Hyber invites us to re-evaluate our representations and to envisage other possibilities, other attitudes and other behaviours in our relationship with our environment, by working back and forth between the in situ and the in visu⁶.

His paintings, which are the result of a mental and organic process with multiple entanglements, are like palimpsests that need to be deciphered. They exude a pessimistic atmosphere, reinforced by the diluted colours, ‘dirtied’ by the dust of the charcoal. However, this pessimism is counterbalanced by the assertive positivism of Fabrice Hyber, whose approach can be likened to that of a precursor of ecological art such as Alan Sonfist⁷. This positivism, which reflects his belief in progress, rationality and the human capacity to improve things through action and science, is expressed in a whimsical way in Acid, where the artist proposes aeronautical solutions to escape the consequences of acid rain. In La Vallée (2022), he depicts a real place, illustrating the importance of trees in hydraulic regulation, the point of intercession between heaven and earth. This painting reflects the artist’s reflections on the evolution of his living and working environment, which he imagines as a cultural and ecological place of transmission, exchange, meetings with artists, scientists, philosophers, etc., as well as agrarian and animal husbandry experiments.

The other part of the exhibition, ‘La Fabrique du paysage’, is organised around installations and P.O.F. that illustrate the climatic theme. In the museum’s patio, we find Climat, an assembly of refrigerators with their doors open, supposed to act as air-conditioning for the site. It is a far cry from the conceptual subtlety of Art & Language’s Air-Conditioning Show. In the Abbaye Saint-Jean d’Orbestier, two constructions that need to be activated welcome spectators, who can experience the rain in an oversized beach hut (Untitled, 2012), or the wind by opening a kind of container (Maison des vents, 2012), a gag work that takes the wind out of your sails, but lacks the finesse of Ryan Gander’s I Need Some Meaning I Can Memorize (The Invisible Pull). More illustrative, the elegant inflatable sculpture of a half-cloud in the process of raining fits perfectly into the space of the nave. In the heart of the room, L’Homme de terre de 2023 (The Earthman, 2023), akin to his P.O.F.no 123, in a way sums up the artist’s universe, which is concerned with making nature’s capacity for regeneration visible, by entrusting the public with the responsibility of (re-)giving life to the seeds that might grow by watering this earthen bed. An ode to the life drive.

The multiplicity of paths taken by Fabrice Hyber may destabilise us, but it confirms that the vital force of the artist is the prerogative of geniuses. The diversity of his projects reinforces this observation: the installation of a fountain in the Jardin des Plantes in Nantes – based on his Bessine man, who has become a wooden Gulliver spitting from time to time – the project [E.F.1] project for a gigantic fresco for the Shanghai metro, a monumental fresco project for the neo-Gothic church in his village of Château-Guibert and the creation of stained glass windows using a complex technique developed by the artist, a remake of his forest in Chile, and so on. The fact remains that it is by creating La Vallée, his own remarkable ecological estate, following the example of the picturesque Italianate Garenne Lemot estate in Gétigné, that Fabrice Hyber is certainly working best for his posterity; sow and sower.

1. Fabrice Hyber, La Vallée, Paris, Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, 2022.

2. Alexandrine Dhainault, ‘Fabrice Hyber, Prototypes d’Objets en Fonctionnement’, Revue 02, 2012 [E. F.1].

3. See the caricatures of Jean-Jacques-Isidore Gérard, known as ‘Grandville’, or Honoré Daumier.

4. Alexander von Humboldt, Cosmos. Essai d’une description physique du monde, Paris, Gide and J. Baudry, 1855-1859, pp. 377-378.

5. Georges Didi-Huberman, Atlas ou le gai savoir inquiet. L’œil de l’histoire, 3, 2011, Paris, Les Éditions de Minuit, pp. 137-148; J. W. von Goethe, ‘Histoire de mes études botaniques’, 1831, p. 185 and ‘La Métamorphose des plantes’, 1790 , p. 209, in Court Œuvres d’histoire naturelle, Paris, AB. Cherbuliez et Cie, 1837.

6. On the concept of artialisation: Alain Roger, Court traité du paysage, Paris, Gallimard, 1997.

7. Bénédicte Ramade, Vers un art anthropocène. L’Art écologique américain pour prototype, Dijon, Les Presses du réel, 2022, pp. 58-60.

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Céleste Richard Zimmermann,

Related articles

Gregory Sholette

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Vera Kox

by Mya Finbow

Yoan Sorin

by Pierre Ruault