Gregory Sholette

« The artworld only functions thanks to its dark matter »

Currently, art, as well as its worlds, actors and networks are radically changing and thus remapping what is possible or not. These evolutions, while rooted in a techno-material process, only appear clearly to us once their description has itself been made possible. The words, concepts, and images through which we are thinking about art are indeed often perpetuated without prior examination in art’s historiography and through its critical habits. New York based artist, writer and activist Gregory Sholette undertakes the work of excavating and clarifying the hidden workings of the artworld. The aforementioned reasons make his task an invaluable contribution to anyone wishing to conceptually equip themselves to better reflect on the present in an emancipatory way. Sholette’s writings deal with questions of class, representation, workerism or collectivism in the arts by coining powerful and telling concepts, to which this interwiew hopes to provide a first approach in French. He has, amongst other, published the following books in English: Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture (2010); Delirium and Resistance: Activist Art and the Crisis of Capitalism (2016); The Art of Activism and the Activism of Art (2022) et co-édité avec Blake Stimson: Collectivism after Modernism: The Art of Social Imagination after 1945 (2007).

You have been active in the field of art, activism, and education since the 1980s. To start with your personal trajectory, how did you initially get involved with art and activism?

Gregory Sholette – I was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in the United States [in 1956]. I had very little in the way of professional role models. Nobody I knew was an artist; nobody was doing any kind of cultural work. Around me, people were either civil servants or getting jobs in factories, like my brothers for instance whom I later wrote about. (1) I used to work the late shift as a janitor at a computer mainframe fabricator. I would go there after I went to art classes at the local community college, a two-year college for working class people. There, I studied with sculptor Charlotte Schatz, who taught me about the Soviet Avant-Garde. (2) Ultimately, I decided to apply for a Bachelor’s degree in Fine Art (BFA), and wound up at The Cooper Union in New York City. I moved there in 1977 at a time when the city’s infrastructure was in shambles, but with a very lively, underground art scene.

You might say before I moved to NYC, that I was already an activist, but without truly understanding US Left politics. That changed once I arrived here. I rented a room from an 81-year-old woman who had been born in Ukraine before the 1917 Russian Revolution. Her name was Sophie Saroff, daughter of a progressive-minded Rabbi who sent her to school, and after arriving in the US she became active in labor unions, then joined the Socialist Party of America (SPA) around 1901. Sophie later left to join the Communist Party when the SPA splintered in 1919. She had an amazing life, and I was completely reeducated about the American Left and its labor history from her, something that was not taught at most schools in those days, any more than one would have learned about slavery, or the violence against Indigenous peoples, that are nevertheless so much a part of what the US is about.

What were some of the other historical figures that were important to you, and more importantly perhaps, how did you learn about them? I am asking about this specifically because of this other, more hidden and non canonical history that you are following in your scholarly work…

GS – I already mentioned Sophie Saroff, who was not an artist, but who was very important to me. I also had a wonderful art teacher when I was younger, as my parents had recognized my art tendencies and sent me to a local water colorist whose name was Jeanne Doan Burford. I bring her up not only because she helped point me towards a future outside of whatever I would have ended up doing, which would probably have been getting a job at the local post-office. And I am purposely naming these less “famous” influences because of the significance of what I call the “dark matter” of culture: the mass of producers who go unrecognized by the art world, but who nevertheless are essential to its maintenance and reproduction. Still, I have been shaped by other, better-known individuals including the German artist Hans Haacke who was my professor at The Cooper Union, the critic and activist Lucy Lippard who I met after graduating, and the Feminist Marxist art historian Carol Duncan who I credit with shaping my approach to writing in an accessible, and therefore not ultra-academic way.

Some of your key concepts were formulated in relation to the socio-economic context that led to the protests of Occupy Wall Street (OWS). I am thinking here about “dark matter”, “bare art” and the “missing mass”. To provide a short introduction to your thinking, what led you to conceptualize these notions at the time?

Actually, I first introduced the idea of artistic “dark matter” or art’s “missing mass” as early as 2000, and only fully developed this into the book Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture some eight years later before being published by Pluto Press in 2010. So it was completed just as the financial crash of 2008-2009 got underway (I discuss this in the introduction), and therefore before the so-called Arab Spring and OWS took place in 2010 and 2011 respectively. However, there is no doubt in my mind that the Dark Matter thesis was informed by many of the same sentiments of these movements, including the idea of the 99%. Which is to say that class has always been an important framing concept for me, and it runs like a red thread throughout my writings, organizing, teaching and artistic practice, along with a focus on issues of historical representation, artistic collectivism, and cultural labor emerging from within what I call the “Phantom Archive”.

What I sought to convey with my concept of artistic dark matter was an affirmative approach to dealing with class and other excluded practices and people left out of traditional historical narratives. Put in the form of a question: How does one articulate that which has been excluded or marginalized within the artworld but without reproducing its process of canonization of a select group of artists and movements? My argument was, and is, that the artworld only functions thanks to its dark matter. This missing mass is constituted by the many people who studied art and completed some type of professional degree, but who are now installing walls in the museum or art gallery, or who are transporting other artist’s paintings to and from exhibitions, or who make the lattes in the museum café. Nevertheless, many of these individuals are still trying to continue their art making, but in order to survive they carry out the type of work that makes the broader institutional artworld function. They are right there, you see them, but you don’t see them as artists. They are invisible in plain sight.

However, and most importantly, I added that thanks to these same changes in this dark matter’s visibility, there was the possibility for some factions of this missing mass – those unseen creative workers who embraced the need for progressive political change in particular – to develop new forms of collective agency. What made this hope even more realizable was the fact that most of this dark matter missing mass already operated within a gray or secondary economy of mutual assistance that had been developed out of necessity. This seemed to me to offer an alternative foundation for substantially changing culture more broadly.

Do these concepts describe a certain historical situation which would now be over, or can they still be applied to our current era?

Things have changed, yes, although in some ways these changes were already proposed by the book Dark Matter, and in other ways they were unforeseen. One of the book’s central themes in 2008-2010, was that this so-called missing artistic mass was already getting brighter. And this was taking place for two reasons, including the spread of networking communications media, primarily by way of the Internet, which was illuminating all kind of spaces, people, ideas, cultural formations that had been invisible before. Suddenly, almost anyone could share content and essentially stake out a claim within the cultural sphere more broadly. Importantly to me, the internet had a powerful role in drawing out forms of collective practice that were not visible or social bodies not previously connected, permitting them to recognize their own cooperative capacity. Of course, it still took some time before this self-affirmation would impact the sphere of fine art, but certainly that has now taken place some 15 years later.

The second reason I suggested that Dark Matter was getting brighter was due to the rapacious nature of neoliberalism which was quickly replacing the traditional welfare state. In brief, after a period of declining profits (as proposed by Marx) in the post-World War II era, capitalism was seeking new ways to extract value. Thus, we find it diving into all sorts of dark corners to mine previously invisible forms of social labor.

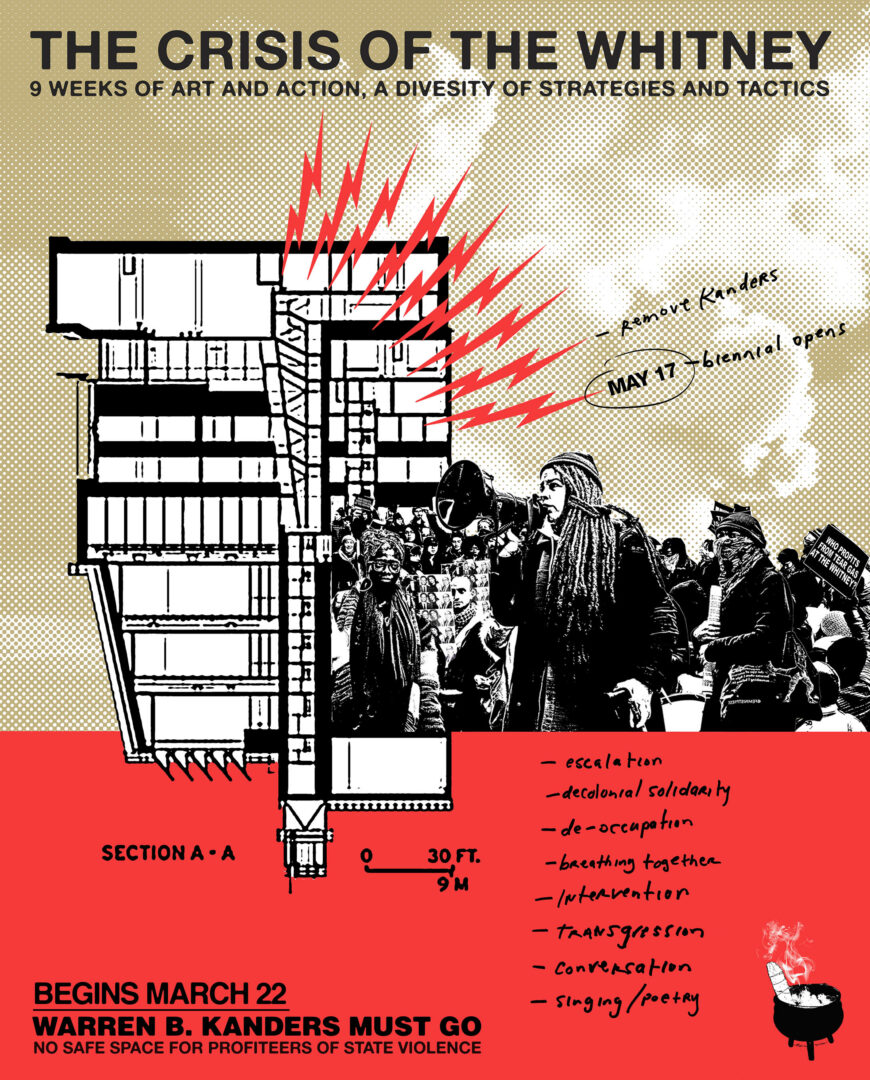

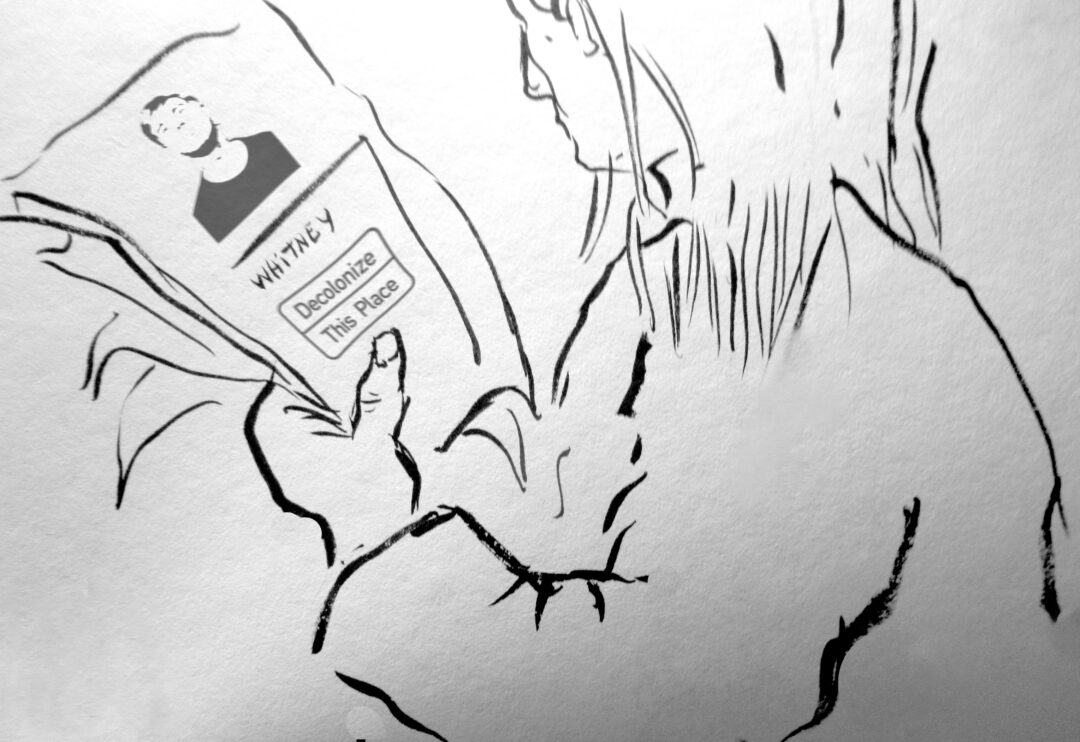

Whether actual value can be realized in this way is beside the point, but what is clear is the way a once invisible mass of production and producers has been illuminated. In the realm of art, we find museums, biennials, and even commercial galleries recognizing forms of collective and even politically activist art, as well as many artists previously spurned by the art world including people of color, women, Indigenous and LGBTQ communities. However, we also find disturbing networks of Alt-Right, ethno-nationalist and fascistic culture that are now brought into the light in ways unavailable to them before.

Let’s now speak about your last book The Art of Activism and the Activism of Art (2022). These past few years, artist groups and collective have been making a come-back. This is also one other of your key research topics since as early as the end of the 1990s, as exemplified for instance through the book that you co-directed with Blake Stimson, Collectivism after Modernism (2007). I feel that one of the main differences is that they are now celebrated by the mainstream artworld. Why are collectives so popular nowadays?

Yes, this helps make my last point. I start off the book The Art of Activism and the Activism of Art (Lund Humphries, 2022) talking about the questionnaire on the Tate’s website, “Quiz: Which art collective do you belong to?” In the past, a major art corporation like the Tate would have excluded many of these groups from recognition, let alone from entering its collection. Now, it is celebrating them and even offering a discount once you take the test so that you can go in their café and get that latte served by some unknown artist. But ironically, the Tate’s staff were on strike about one year after they created this website in 2019. Many employees were facing redundancy due to the COVID epidemic, so claimed the Museum’s administrators. So, you have this questionnaire, featuring these formerly ignored art collectives, some of whom were very politically activist, and yet all these workers were outside on the picket line protesting what the corporation was doing. I find that quite stunning: the Museum simply took in the idea of the collective and they made it part of their own narrative without acknowledging what these art collectives would have thought about the strike. I suspect that most of them would have left the museum to go out and protest.

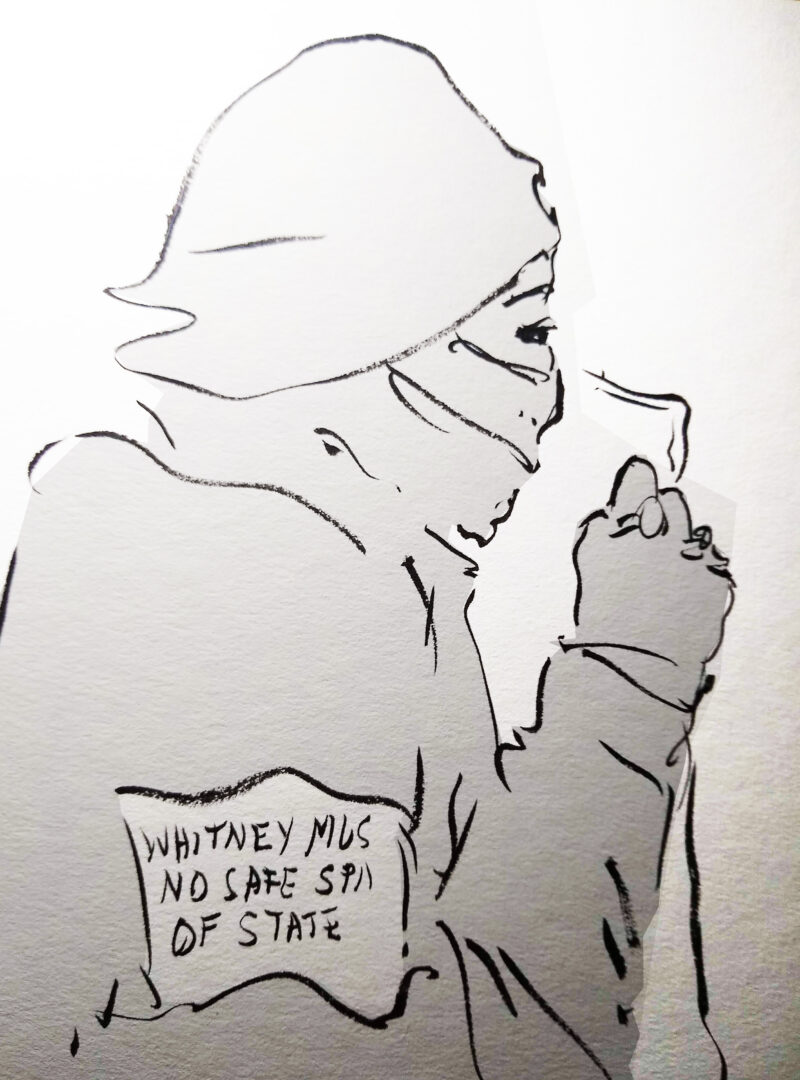

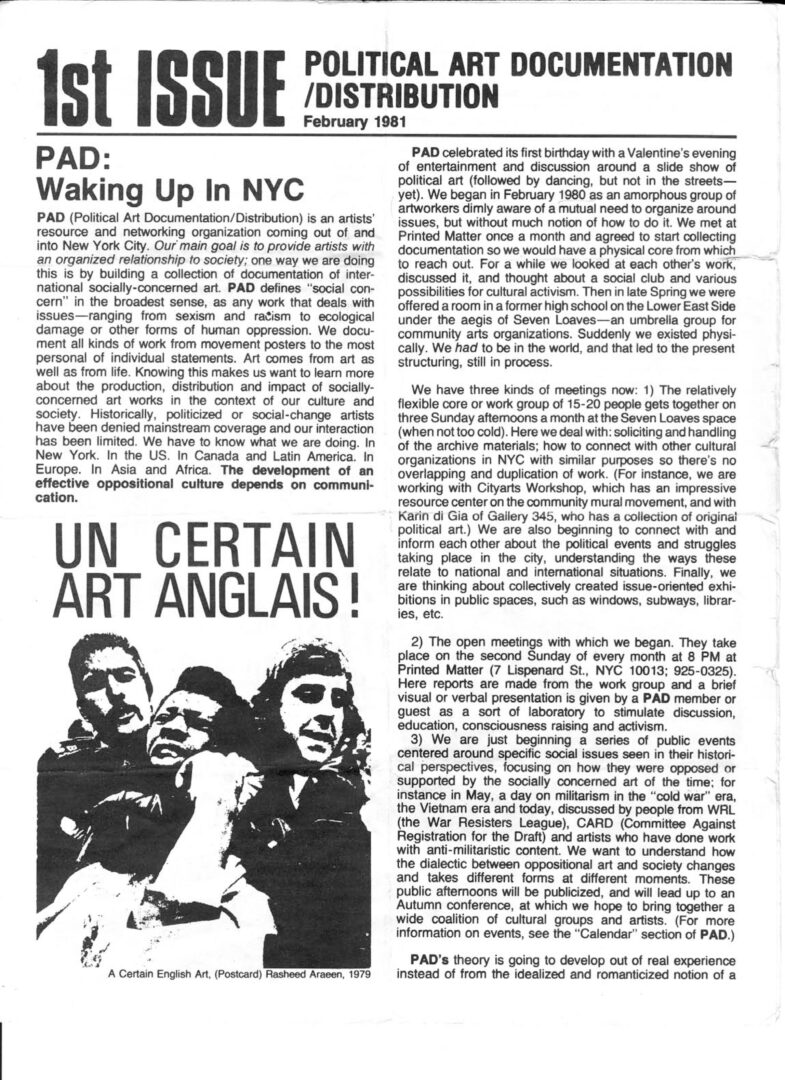

The other thing I pointed to was that Black Lives Matter was named as one of the top 5 art world influencers for 2020 in the magazine ArtReview. This is a phenomenal change: when I started doing activist work with Lucy Lippard and others, with whom I co-founded the organization PAD/D [Political Art Documentation/Distribution] in the beginning of the 1980s, we were really on the margins. Now, suddenly, the artworld wants to embrace to idea of activism, collectivism, and social practice. That does not mean the mainstream art world is not careful in these curatorial selections, but it definitely signals a significant change. But I also note that Black Lives Matter (BLM) is not really what you consider an art collective, so something else has taken place in which political activism (such as BLM) plays a notable role within the realm of aesthetics. That is curious. Something similar was proposed by theorist Yates McKee who, in 2017, described Occupy as a kind of art project or art work. (3) My last book seeks to expand on this ontological fluidity between art and activism suggesting that it is a result of the type of ravenous capitalism always in search of new sources of value and consumption. The result is that we live in an aesthetic of capitalism where the spectacle of commodities and the practice of politics are superimposed if not actually merged.

One last question concerns what you call “shadow archives” or “phantom archives”, another notion that is of particular importance in the last book. Can you elaborate on what this idea means to you, in terms of authorized narratives and writing art history?

The influence of the dark matter concept has exceeded my expectations, but the more trenchant question might be: Why do I even keep writing about these matters if dark matter is illuminated, if collectives are accepted by the art world, if activism is now a type of commodified culture? I don’t have a good answer to that, except that I am at a point now where my critical focus is turning to questions of time, or perhaps we could say temporal politics. For instance, for my next book, I will go back to reflect on the Federation of Artists that was founded during the Paris Commune of 1871. I am interested in the type of structures these socially-engaged artists were experimenting with, and how and in what ways these concerns have repeated throughout time on up to the present. And I hope to approach this history in a non-linear way using a concept I have been developing that I describe as a “Surplus Archive”, or simply a “Phantom Archive.”

Think of this Phantom Archive as a messy collection of social, political, economic, and cultural experiments, failures, dead-ends, as well as now and then a few successes. It is not a cannon of great names in the pages of art history nor even about a great march of historical progress or transformation, but seeks to replace these linear notions of time with a fragmented and boisterous “hauntology”, which is of course

Jacques Derrida’s neologism for an unsettled obligation that emanates from either the past or the future, or both simultaneously. This is why, I believe, many activist-artists today create work while not even being consciously aware of this past, whose off- screen presence nevertheless shapes what they do. If I have a hope, it is to focus on more conscious ways of repurposing and repairing aspects of this Phantom Archive as a way of holding the line against the types of anti-progressive authoritarianism we see across the globe (4).

- See : https://makingandbreaking.org/article/the-swampwall/

- See : https://michenerartmuseum.org/exhibition/charlotte-schatz-industrial-strength/

- Yates McKee, Strike Art: Contemporary Art and the Post-Occupy Condition, Verso, 2017.

- Greg Sholette travaille actuellement sur une nouvelle chronique à ce sujet pour la revue FIELD – Journal of Socially Engaged Art que publie Grant Kester et qui paraîtra en février. Voir : https://field-journal.com/

Head image : PAD/D « Image War on the Pentagon » placard protest march in New York City, 1981. Image: courtesy of the author’s archives, for first demonsatration see: https://research.moma.org/padd-archive.

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Dena Yago, Simon Fujiwara, Michael Rakowitz, Paul Maheke,

Related articles

Biennale Son

by Guillaume Lasserre

Lou Masduraud

by Vanessa Morisset

Bharti Kher

by Sarah Matia Pasqualetti