Merlin Carpenter – “What’s so elastic about you ?”

archive élastique

Synagogue de Delme, 24.10.2020-29.09.2021

Curator : Benoît Lamy de la Chapelle

Heavy Burschi (Heavy Guy)

In 1989, Martin Kippenberger asked his then assistant, Merlin Carpenter, to produce around fifty paintings based on their reproductions in a catalog dedicated to his work. Kippenberger photographed all of the paintings produced by his assistant, printed them on a scale of 1 and hung them on the wall in an installation he called Heavy Burschi (Heavy Guy). The “originals” were partially destroyed and thrown into a dumpster in the middle of the room. Kippenberger, the employer, assumed the right to demolish the work of Carpenter, the assistant, while he simultaneously included him in his iconoclastic and conservative logic, which consisted in destroying in order to better regenerate and re-inject elasticity into a medium whose practice had been made impossible by too bulky a history. In 2006, Merlin Carpenter made a similar move by asking his gallery owners and collective of artists Reena Spaulings to work for him as assistants and to reproduce images of September 11 in the abstract style of another very bankable artist of their gallery, Josh Smith.

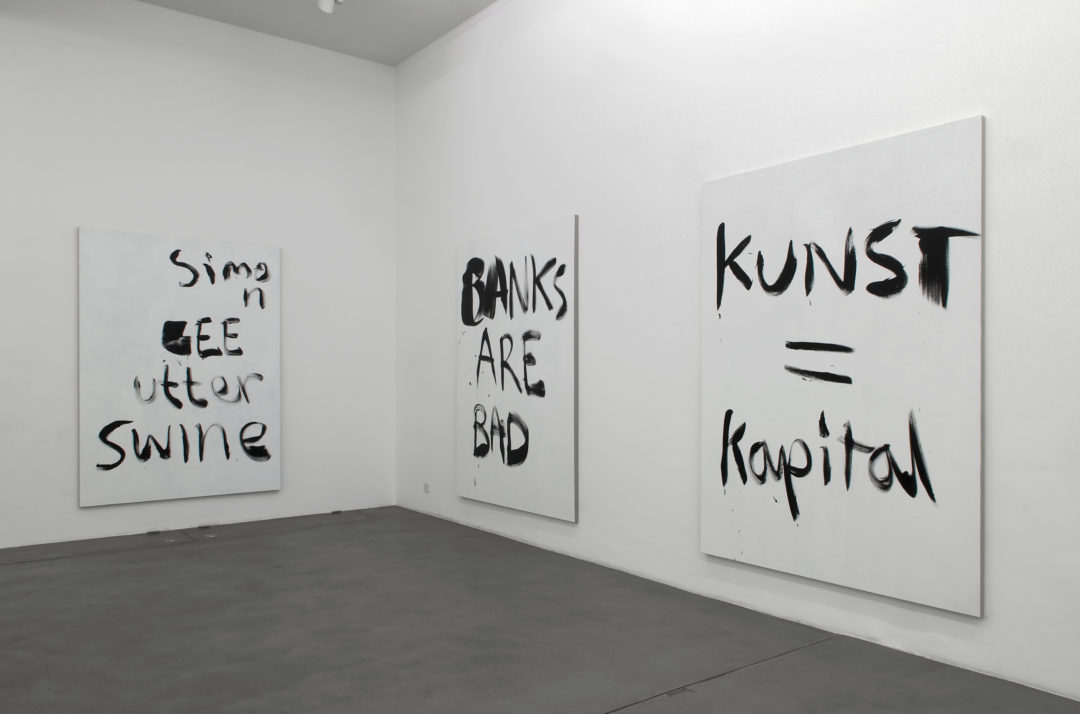

It is sat on this conceptual elastic – the work could be anything, made by anyone, shown or smashed to smithereens, necessarily kitsch in its attempt to be political – that Merlin Carpenter, who calls himself a “painter-artist”, has been working since the early 1990s. An elastic that allows him to either paint personalities and ducks with a certain figurative talent, or to exhibit paintings concealed by transport covers; to pick up a paintbrush the night of the opening to cover white canvases with insults against banks and his gallery owner, or to spend the production money on luxury products. As Isabelle Graw recalls in her interview with the artist,1 stretcher bar painting became established during the Renaissance due to its malleability and its capacity as a fluid commodity to be moved from one context to another. In this sense, Merlin Carpenter’s practice consists in fusing the painting as object with its commercial essence and resulting logistics: Long Title (2017) is a wooden storage pallet attached to the wall; Do Not Open Until 2081 (2017), a series of canvases sealed in their cardboard packaging; Circuits (2020), electrical circuits sketched in black paint on a white background. Accordingly, painting becomes sheer expenditure or consumption, where the financial meets the energizing and where the artist squanders (himself) away. In 2013, Merlin Carpenter transported his works himself – pieces of the iconic Burberry tartan mounted on stretcher bars – during the Burberry Propaganda Tour, a tour of the former Eastern bloc, whose sakes obviously did not lie in presenting the work but in testing the meaning of such a transposition to the land of Marxism.

Therefore, it is not surprising that in the French town of Delme, the artist focused on the regional road that runs along the art center and connects Metz to Strasbourg in a chorus of heavy trucks. Considering this merchandise distribution road link, Merlin Carpenter turned the art center into a warehouse for the storing of 700 empty cardboard boxes stacked on top of each other. A forklift, too big to fit into the old synagogue, was parked in front of the entrance. Far from any form of hyperrealism, the artist wasn’t seeking to render the illusion of a real warehouse, or suggesting such an activity by stacking immaculate boxes systematically taped the same way on intact pallets. This gesture revisits a certain minimal tradition and primitive forms of institutional criticism. In light of Michael Asher’s radical interventions conducted in the 1970s to take the institution apart, Merlin Carpenter rather sought to obstruct it or fill it in, to better materialize its available volume. Opened in October 2021, the exhibition was designed during the Covid-19 crisis, which, by modifying distribution channels, renewed storage needs as cultural venues were forced to remain closed. Carpenter feeds the absurdity of these injunctions by staging the transformation of the place into a functional space apparently optimized though empty and useless, housing one single commodity: the installation itself. He effectively questions the elasticity specific to this former synagogue, which became an art center that might actually be converted into a warehouse – if we are to believe the political maneuvers or the abolitionist tendencies that call for its closure. Merlin Carpenter’s installation poses an equation without resolution: that of the art center standing at the crossroads of a place of worship and a storage space. In other words, it oscillates between ritual logic and a market one – an already tense knot of contradictions that needs only to be pulled.

It is interesting to notice how Merlin Carpenter’s reflection and actions lean against the various crisis episodes of the early 21st century, and what the concept of storage embodies in relation to them. It is a good indicator of the conservation needs and priorities that are expressed at the time of a shift of paradigm that reconfigures the motions of capital. In that regard, Merlin Carpenter’s installation reminds me of the story told by the American artist Justin Lieberman in the afterword to his book The Corrector’s Custom Pre-Fab House. Shortly before the 2007 subprime mortgage crisis, while working on one of his most ambitious pieces, the artist took out a loan to buy a house in Upstate New York on the advice of his gallery owner. A complex financial logic of investment and debt was then set in motion around the production of this work – a metal igloo filled with consumer items that Lieberman listed in a software program. The artist completed it shortly after the onset of the crisis. The merchant who had offered the house for sale failed to make any successful transactions and stopped paying for its storage. Justin Lieberman then mortgaged his house and did not manage to find a way to store the artwork. The whole sculpture went to waste, except for the computer program that was used to browse the various items that make up the artwork and would allow it to be shown years later in a different form at Confort Moderne in Poitiers, France. There, an image of the original sculpture was printed on a tent that you would slip under in order to browse the work’s textual archive.

Economic austerity will therefore have reaffirmed an old dynamic: “the lower the percentage of material to dollars, the better, particularly in relation to moving and storage.”2 The logic of the art market crushes the cumbersome materiality of the pre-fab house without destroying it completely, compressing it and endowing it with a more competitive elasticity.

The Holzweg

Between the columns of cardboard boxes that recall the architecture of a data center, the title archive élastique gives us food for thought. The boxes retain nothing of the activity of the person who stored them there, except for the radical and disillusioned gesture of the artist, who is aware that the slightest of his provocations or evasions on his part will easily integrate the logics of the institutions and the art market channels. Simultaneously, these provocations and evasions continue to influence several generations of artists who reinterpret these gestures in the light of feminist issues and trans-identity positions, emphasizing the share of humor or avowed vulnerability that they contain. Thus, on her exhibition’s opening night at the Balice Hertling gallery, Jade Kuriki Olivo, alias Puppies Puppies, resumed the protocol of The Opening by inscribing the words “Anxiety” and “Depression” in black paint onto white canvases.3 As for Magasin (un opéra), a “pop-up store” selling navy blue and brown sweaters that Fabienne Audéoud intends to set up in all over France, it reinvests a similar logic to the Burberry Propangada Tour’s. It is then perhaps in its legacy that lies the elasticity of a practice which otherwise allows for little leeway of experimentation, given the allocated context and the fact that it is preconstrained by potential co-opting. Merlin Carpenter’s proposals test the possibility for actual unproductiveness in the attitude – which was, according to Josef Strau,4 the particularity of the Cologne scene from which Kippenberger and Carpenter came – as well as for institutional criticism of which he is the target in the first place, in that he is no longer that different from the institution. His forms of positioning are ready-made even before he performs them.

In a 2012 interview with Reena Spaulings, Merlin Carpenter brings up the idea of the “wrong turn”, of going the wrong way, which in German is often called “Holzweg”.5 This is an interesting metaphor when we consider the recurrence of a “circulating” feature in the artist’s practice as well as his experimentation with a form of negativity or dead end, a path that leads nowhere. In Delme, Merlin Carpenter does not really play along with the exhibition game, though neither does he suggest that something else should be happening there (which he could have done by collaborating with a carrier company and placing the art center on a new track). He submerges the building, but not quite all the way to the top, leaving some space under the dome; he blocks it, but not quite all the way to the end, thus preventing any conclusions or new productive leads from taking shape. Later on in the interview, Merlin Carpenter notes that “Holzweg” has another meaning: “to be lost in the woods.” And when one wanders through the aisles between stacks of empty boxes, the cardboard data center begins to look like a forest out of which no path seems to take shape – to reach the outside and do what anyway? Merlin Carpenter made it clear in his book “The Outside Can’t Go Outside”6: here below, the outside does not exist.

- “Painting as a cover story, a conversation with Merlin Carpenter”, in Isabelle Graw, The Love of Painting – Genealogy of a Success Medium, Berlin, Sternberg Press, 2018, p.183

- Justin Lieberman, The Corrector’s Custom Pre-Fab House 2009-2015, Poitiers, Le Confort Moderne, 2015, p.76

- Puppies Puppies, “Anxiety, Depression & Triggers” at the gallery Balice Hertling, Paris, 2019

- Josef Strau, “The Non-productive Attitude”, in Make your Own Life. Artists In and Out of Cologne, University of Pennsylvania, 2006

- “Welcome to the Tate Café. A conversation between Merlin Carpenter, Emily Sundblad and John Kelsey”, Paris, March 2012, http://www.merlincarpenter.com/TATECAFE.pdf

- Merlin Carpenter, The Outside Can’t Go Outside, Berlin, Sternberg Press, 2018

Image on top : Merlin Carpenter, Sans titre, 2020. Manitou 1440, chariot élévateur télescopique (14m), dimensions variables / Manitou 1440, telescopic forklift (14m) variable dimensions. Vue de l’exposition / Exhibition view of « archive élastique », Merlin Carpenter, CAC-La synagogue de Delme, 2020. Photo : OH Dancy.

- From the issue: 98

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Corentin Canesson, Jacqueline de Jong, Celia Hempton, Madison Bycroft, Charles Atlas,

Related articles

Performa Biennial, NYC

by Caroline Ferreira

Camille Llobet

by Guillaume Lasserre

Biennale Son

by Guillaume Lasserre