Mircea Cantor

The first piece in the Mircea Cantor show at the Chapelle de l’Oratoire, part of the Nantes Museum of Arts, could almost singlehandedly sum up the artist’s praxis. It is a sentence in the form of an anti-slogan, uttered by one of his children, expressing the artist’s wish not to play at being a saviour of humankind, and not to overstep a role which he fondly intended to be a modest one. I Decided Not to Save the World is an example of ventriloquy. The artist got his child to utter it rather than doing so himself, favouring a distanced relation to the world. By highlighting the figure of a child going through many different situations with the same playful and somewhat mischievous smile, Mircea Cantor neutralizes the much-expected solemnity of right-thinking discourse. As part of the Romanian season initiated by the Institut Français, the invitation offered to this fleeting Nantes resident seemed a must: his visit to the city has been decisive for his career. The circuit round the show at the Chapelle is not exactly a step backward to the years of his training, but it does have a marked retrospective character where quasi-souvenir photos mingle with key features of his work. The place earmarked for the city is decisive, and this can be easily understood, because it reflects the years during which a very young artist matured.

Lost bearings

Mircea Cantor is a product of the fall of the Ceausescu dictatorship and his country’s sudden entry into the great European circus: remember the atrocious fate of that grim despot of the post-Stalin era, a persistent anachronism in the ashes of a USSR teetering prior to an unexpected revolution, which put a violent end to that chaotic dictatorship and then tipped the country over into the attraction zone of a then magnetic Europe. The unexpected invitation he received from Robert Fleck, director of postgraduate studies at the Nantes School of Fine Arts, when he had not yet graduated from his own academy, hastened the westernization of that young artist, helping him to hurry through the stages of recognition, and catapulting him to the summits of the Paris establishment (he then swiftly joined the Yvon Lambert gallery, one of France’s most influential galleries at the time). Even when Cantor’s work does not seem to be excessively affected by this (voluntary) exile, clues do nevertheless emerge, now and then, setting up a nostalgic vision: so we find the series Irréversible (1992), with all the attributes of amateur photography, which, in effect, corresponds to the pre-history of the artist’s activities, illustrating as it does his attachment to a period prior to Romania’s entry into the Europe which would usher in decisive changes to the organization of landscape, and in particular of small gardens around suburban homes—come to mind the words of Jacques Dutronc’s song, “please, Mr. Promoter, don’t damage these flowers.” In another series of photos where he is playing with his young girlfriend (Another Senseless Fight, 1999), we can make out his native town of Cluj: the atmosphere seems pretty much that of an Eden-like Heimat, just before the country was caught up in the harsh reality of economic priorities. Having lost his bearings, the young artist arriving in Nantes was undoubtedly disoriented. One of his earliest striking works, which in a way opens the exhibition, presents this “disorientation” (All the Directions/Toutes les directions, 2000), after his visa for the United States had been refused: the photo taken in the midst of his adopted city shows the artist hitch-hiking, holding a sign showing no destination: this is one of the first times that the artist presents this kind of absence of statement which we will subsequently find in his videos of demonstrations. Indifference towards the avenues opening up to him, acceptance of an essentially unpredictable fate, or quite simply an expression of a young man’s disillusionment, when he has been promised the world, and ends up a victim because he belongs to a country that is not yet taking part in the great concert of western nations: in a word, caught up with by his own past.

Wit as an antidote to bitterness

But the young artist already knew that it served no purpose to let bitterness invade him: at the same moment, or almost, he offered us a witty work making fun of the city by producing phony ‘twin towers’ using simple photoshop tinkering to duplicate the Tour de Bretagne/ Brittany Tower in Nantes, and making a premature fake representation of it: “I feel in Nantes like in New York” is a ‘lite’ criticism of the tendency of provincial cities to try and measure up to large international metropolises: the artist is relieved of all the weight of the city supporter who feels obliged to defend it, for he has the de facto ability to open the eyes of its inhabitants to what they are no longer managing to see, the excessiveness of architectural propositions which refer solely to the hubris of their promoters, without taking urban harmonies into account. With this modest but highly effective work, we feel the advent of the playful and subtly critical dimension that will be asserted throughout the years when the artist’s work was maturing. But Cantor’s art never lets itself be framed by a flattening reading: if most commentators on his œuvre tend to see in it a “poetic” dimension, this is because of a linguistic ease which shrouds the complexity of a work that cannot let itself be reduced to one interpretation or another. We certainly find recurrences, such as that of the “demonstration”, which has a major and nothing if not surprising place in his work: in the museum, the two “videos of demonstrations”, which are constructed on the same principle, respond to each other from one end of the chapel to the other; one filmed in Tokyo last year (Adjective to Your Presence, 2018), shows a group of young people brandishing transparent signs, walking through the city’s many districts before the eyes, by turns amused and incredulous, of passers-by wondering what is going on, while, opposite, a formally identical video follows the progress of another group of young people walking through Tirana, the capital of Albania (The Landscape is Changing, 2003). This time around, however, the signs are mirrors. Perhaps the ambient setting (the exhibition opened at the height of Frances’s Yellow Vest crisis) influenced the artist in the way he arranged the show, the fact remaining that it broadly echoed the social situation of the day in France, by adding a nothing if not surprising comment and response to it: what are we to think of such works? In them we can choose to see a criticism of the tools of democracy, and an illustration of the dead-ends of social struggle, but also, and in a deeper way, an ontological dimension, simply expressing the vacuousness of political discourse, watchwords and slogans, compared to the existence of a “demonstration”: it is the performative nature of this latter that provides its ultimate interest, the fact of simply marching through the city in the wake of the incredible permissiveness granted to art, which makes this march possible, when, in a “normal” situation involving making claims, it would have been very problematic to organize. This piece is doubly disquieting, questioning, as it does, one of the very foundations of democracy and highlighting its aesthetic and performative dimension, to the detriment of its social dimension.

Poetic resistance

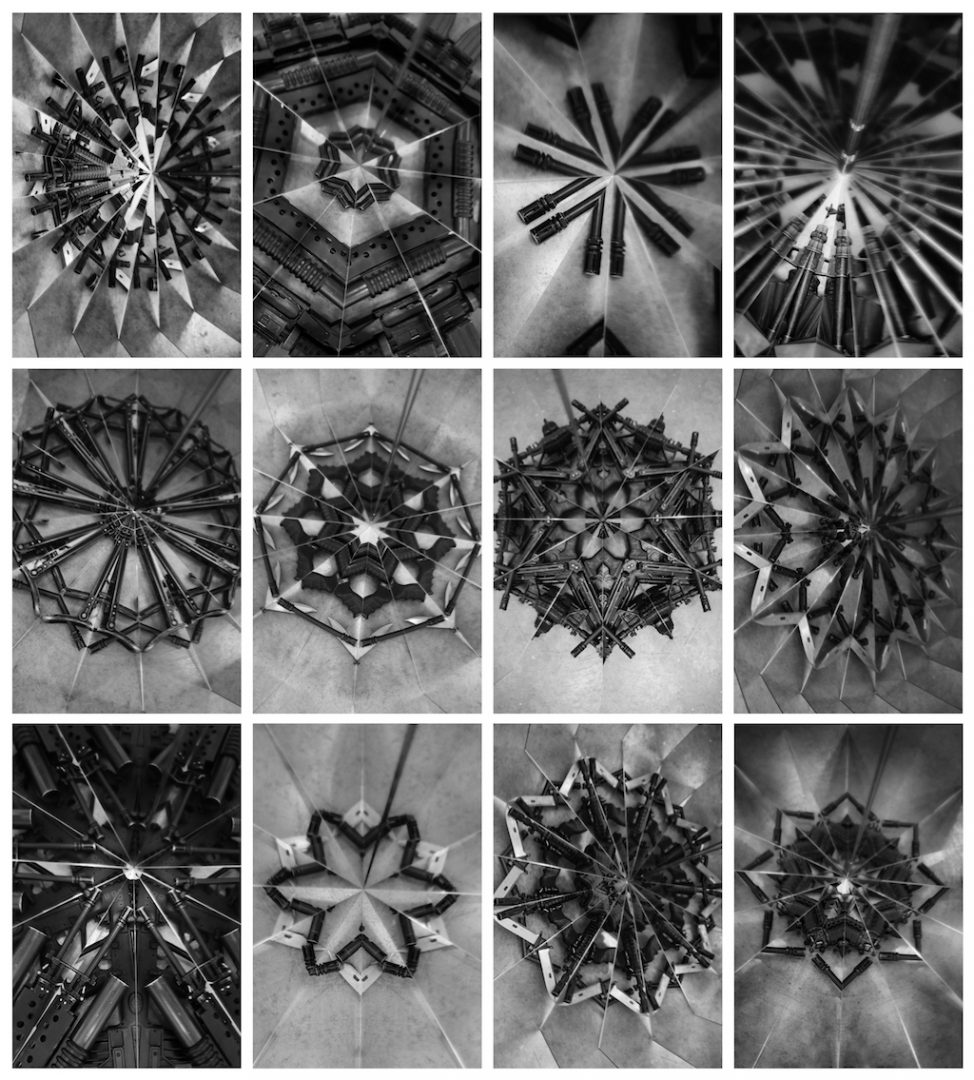

Mircea Cantor is suspicious of collective claims, as we have seen in the two just mentioned videos, but this does not mean that he is indifferent to political issues. Quite to the contrary, many works on view in the Nantes museum exhibition refer to this attentiveness to issues. But it is not part of the artist’s style to become involved in a head-on way. Rather he tries to bypass the issue, lending it an indirect sense, a way for him of displaying a suspicion instead of an art bearing overly precise missions and messages: the piece Holy Flower (2010) perfectly illustrates this “poetic” strategy and, rather than playing with the dramatization of scenes of conflict, the artist prefers to act on the manly representation of arms of war, transforming them into a floral kaleidoscope and riposting, some fifty years later, to the flower power of American hippies keen to put an end to the Vietnam war.

We know the outcome of that fight waged by those “visionaries”: even when they failed to bring an end to the war on the ground, it was by slowly infiltrating minds that they finally brought the hostilities to a close by demonizing the warmongering campaigns conducted by American hawks. Cantor’s work operates by way of this subtle transformation of canonical imagery, and by making an upsetting reversal. Another rather amazing video illustrates this aspect of his work: Aquila non capit musca (2018), where we see an eagle catching a drone. Contrary to the logic of history, which would have the machine getting the better of the bird of prey, the opposite happens, because we are dealing here with real war machines created out of these highly trained eagles: the allegory of the fight between technology and living things is above all suited to displaying the tremendous beauty of the creature which turns out to be infinitely swifter and more fearsome than the remote-controlled gadget. We may also think of the video that introduces a wolf and a doe in the same room, where we see the doe’s heart beat suddenly increase, while the wolf remains surprisingly calm (Departure, 2005). Julie Heintz1 uses the term oxymoron to describe the artist’s image system, but also all manner of literary figures of speech, metaphor, metonym, and the like, duly bringing Cantor’s work into the realm of poetry by way of various methods of activating language: appropriation, hijacking, misinterpretation, oxymorons, as already mentioned, paradoxes, and other forms of licence, which are usually the stuff of poetry. Rainbow (2011), consisting of a rainbow in the form of a barbed-wire fence is part and parcel of the same oxymoronic tension as the two above-mentioned works: if there is poetry in this work, it resides in these impossible encounters. This absolute symbol of freedom and escape represented by the rainbow, used willy-nilly by movements defending nature and travel agencies, to promote the desire for escape, is diverted from its primary symbolism by a violent return to reality; we once again find the artist’s praxis of dealing with “serious” issues by way of appropriation and oxymoron.

But there are images which sidestep any kind of political or other pigeon-holing: one piece in the Nantes show especially catches our attention, showing a clove of garlic dressed up as an onion (Garlic dressed as Onion, 2004): it is hard to see in this work anything other than a pure mental fantasy, something with real levity. Cantor excels in this nonsensical and purely “gratuitous” dimension, which gives free reign to the expression of an unrestricted subjectivity; Shortcuts (2004) can also meet this larksome dimension used by the artist, where we see him photographing short-cuts used by passers-by to shorten signposted routes: nothing less than advocating a “salutary bifurcation”.

The future of art belongs to (my) children

Somewhere between real-estate speculation, which would seem to be the most likely consequence of an attachment to the European Union for his country of origin, paths of peace and freedom barred by barbed wire, and demonstrations powerless to provide meanings other than tautological ones, the least we can say is that the artist does not display any extreme confidence in society-changing mechanisms: is this the same pessimism that has his elder saying in the video Regalo (2014): “I can’t give you anything” (Non posso darti nulla…), signifying the powerlessness of art to change the world? The laconic nature of this utterance refers to the words of the video, which, at the very beginning, alerted us to the artist’s stance and the fact that we should not muddle roles. Art is somewhere else. Perhaps this recourse to his offspring to utter such cumbersome sentences is a deliberate strategy for getting messages across which, if expressed by grown-ups, would have less impact? In Nantes, we find no less than six of these pieces in which boys appear, among them I Decided Not to Save the World (2011), whose title duly has the value of a manifesto; and the masterful Vertical Attempt (2009), which synchronizes the cutting of a trickle of water with a pair of scissors and the sudden interruption in the image flow. The metaphor of the perpetual “flux” of images is also present here and links up with the artist’s concerns about the over-production of imagery.2 But we are also entering the magic world of cinema and childhood, where the fiction of a filmed situation can burst upon reality by way of the action of magic scissors.

Another striking piece, which again presents one of his children, is the one where we see the young boy blowing on knives balanced on a table, and making them fall over like dominoes by producing some “music” (whence the piece’s title, Wind Orchestra, 2010). What is striking here is the gap between the threat represented by the knives, which we feel are sharp, the seeming ban on the child playing with these knives, and the “solution” found by the boy to produce something else, a tune, as it happens: this image is possibly the one we should take home from the exhibition, the mischievousness of childhood as an antidote to the seriousness of existence. Because the world still keeps going forward, “We are part of a universal respiration. When you visit an exhibition, you must be transported by the artist’s reality and not by his or her vision of the world. His or her aim is not to copy reality, but to o er a personal vision of it.”3 When you visit the Mircea Cantor show, you really do get the impression of being gripped by a playful, imaginative, dreamy and poetic breath, which appropriates all the world’s imperfections, and turns them into the raw material for his art, which is to say, just the imponderable: non posso darti nulla, as his child says.

1 “Cantor’s rhetorical forms hence veer more towards allusion and clue. They sometimes make use of metaphor (cutting water) and metonymy (setting fire, signs without names, Le Monde), sometimes of oxymoron (wolf/deer). A study into this aspect of his work would here open up a large number of extremely interesting finds”. Julie Heintz, “The Poiesis of Mircea Cantor”, Înainte, catalogue for the exhibition at the Musée d’art de Nantes, éditions Musée d’art, Nantes, Snoeck, Ghent, p. 30

2 “Then, towards 2005-06, I stopped making images. I’d reached a saturation point, having the feeling that the excess of images killed imagination. With the digital explosion, there were too many images. I said, ‘Enough is enough, I’m stopping, I’m picking up my notebook, I’m writing.’ That was a radical moment when I redirected myself towards drawing and other media”. Mircea Cantor interviewed by Katell Jaffrès, op.cit., p. 82.

3 Mircea Cantor interviewed by Katell Jaffrès, op.cit., p. 86.

Image on top: Mircea Cantor, All the directions, 2000. Inkjet print, plexiglass, 137 × 180 cm. Courtesy Mircea Cantor. Collection Yvon Lambert, Avignon. © Mircea Cantor.

Mircea Cantor, “Înainte”, Chapelle de l’Oratoire, Musée d’art de Nantes, 15.03—15.09.2019

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Jack Warne, Alun Williams, Ben Thorp Brown, David Horvitz, Olivier Mosset, Jean-Baptiste Sauvage,

Related articles

Gregory Sholette

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Vera Kox

by Mya Finbow

Fabrice Hyber

by Philippe Szechter