Tschabalala Self

Artworks by the Harlem-born artist Tschabalala Self (b. 1990) have now been included in roughly 60 public collections across the globe. The artist’s style has been considered as unapologetic or slapstick due to the content of some of her recycled fabric collages, which feature racialized and sexualized figures. Many of these figures are scantily dressed and boast prominent and ostentatious sexual organs while playfully engaging the viewer in an unexpected mise-en-scène involving stereotypes projected onto Black female bodies.

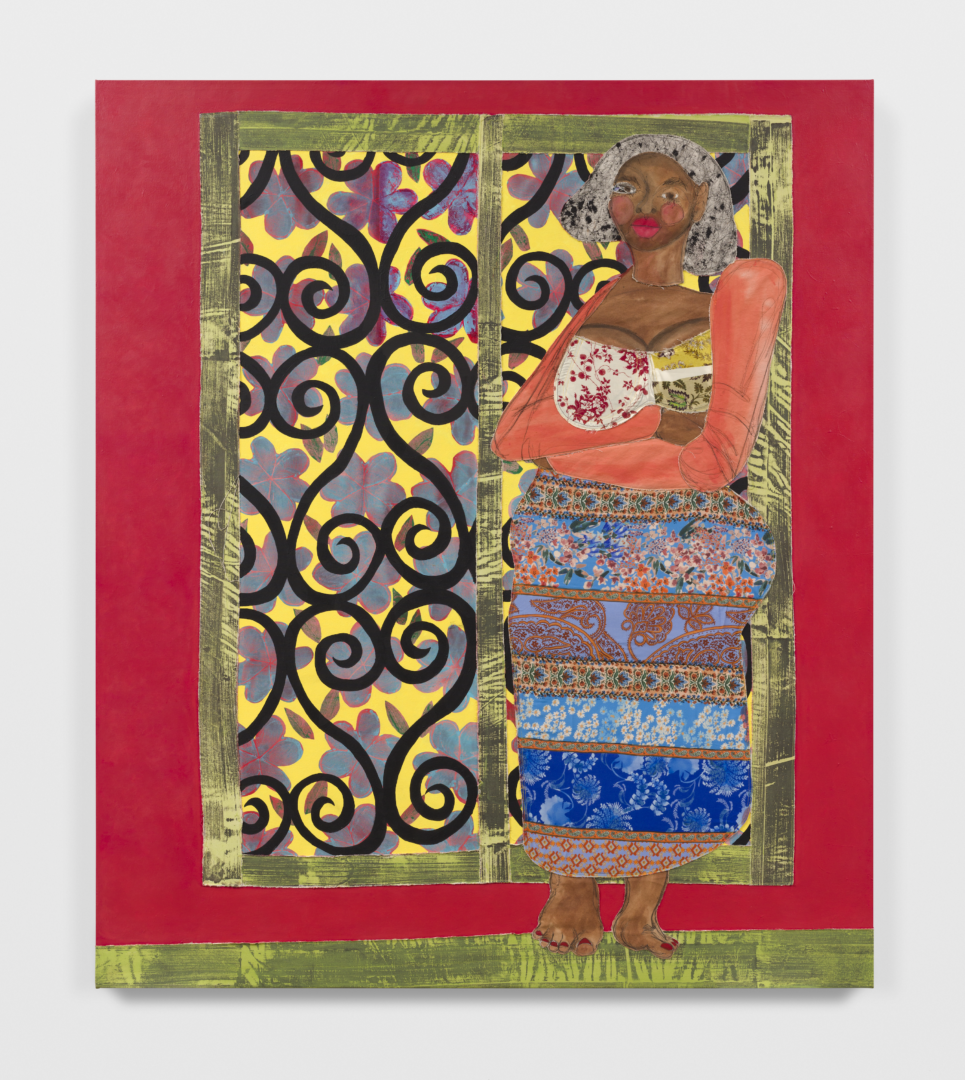

The complex psychological states of Self’s figures are reflected in the whirlwind of stitches, in the juxtaposition of varying structures and colourful motifs which make up Tschabalala Self’s vibrant silhouettes. Her sewn and painted “character-collages” are made up of several parts, signifying a fragmentary existence whose pieces are in a constant state of reconstitution; they are however not without visible fractures.

The artist has admitted to “cannibalizing”1 her own artwork and workshop: this due to a seeming tendency of making use of a kind of “iterability”, as nothing which is repeated is ever exactly the same, instead it becomes something entirely different. Certain works therefore bear the traits and motifs of other similar works, creating a common but discontinuous thread.

The use of traditional quilting techniques—which have been used by the Gees Bend community and Faith Ringgold, whom the artist has met several times—allows Self to experiment with “deconstructing painting” while also reconnecting with historical African-American artistic traditions. This allows her to “gain distance from certain negative or oppressive aspects of painting’s history, reinventing it through the use of the medium.” Indeed, historical representations of Black female bodies in the Western canon oscillate between invisibility and sexualisation. 19th century European painting developed the former example during the same period as the abolition of slavery, perpetuating this form of domination through representation.

Overexposure, eroticisation, sexualisation…Self’s female representations are fascinating and striking at the same time because of the very particular way in which they address these clichés by taking on their exaggerated physical characteristics without denouncing them outright. Depictions of lips, hips, breasts and buttocks expand into bulbous forms. Instead of reproducing racist stereotypes of the sexually-available Black woman, the artist is holding up a mirror to society in order to reflect these oversimplifications back at us.

For the artist, these tropes are “tools, or cultural markers, from which we can gather, visually or subliminally, that consumption and digestion are what is at stake. The idea is that they can be used as a construction or cultural or psychological material, that we can use them to work and to play with in order to create a consciously or unconsciously recognizable image for the audience.”

This type of discourse can also be interpreted as a strategy of reappropriation (one which has also been adopted by the Black Power movement and its use of the “N- word” as well as feminist groups such as the French Gouines rouges, “gouine” meaning “dyke”), which consists of the use of a term initially used as an insult. To use collective fantasies which have been projected onto racialized women’s bodies to serve one’s purposes does not equate the acceptance of them—instead, it can be a way of regaining power over these voyeuristic tendencies.

It is therefore with regard to the gaze that the full ambiguity of Self’s figures emerges—on the one hand, there is the gaze of the viewer, and on the other, there is the to-be-looked-at-ness of these women who seem entirely unconcerned by their visibility. The figures make no attempt at attracting our gaze or attention, and some are completely absorbed by themselves and their environment. They are always on the threshold, in a liminal zone between another person’s line of sight and a kind of private liberation.

These works give us some insight into the existences and private lives of the women. This is due to the domestic setting the artist chooses to feature in most of them. Home serves in this case as a metaphor for an inner psychology: “The home is the site of many foundational ideas, of many of the ideas we have about ourselves, about others. It is a psychologically, politically, and emotionally-charged place.”

In recent exhibitions—“Around the Way” (Helsinki, 2024), “Make Room” (Dijon, 2023), or “Home Body” (London, 2022)—Self explored themes related to interiority and interpersonal relationships in a domestic ambiance where race and gender-related identity politics play themselves out taking into account the fact that private settings can also reflect and amplify the violence experienced in public spaces. “Home is supposed to be a place where you can express yourself freely, or feel at liberty to act or behave however you want, but I think that often, and especially for women, the home can be yet another oppressive place.” This dichotomy between self-realization and confinement can be seen in works like The Thinker (2024), where an excessively high railing with Sankofa motifs belonging to a sliding door resemble prison doors.

Projections of femininity, Self’s characters refer both to the artist’s body and to that of the fictional or historic bodies which inspire her. These women are often depicted in comfortable, seated positions; they are enjoying a moment to themselves, allowing themselves to be idle. The epitome of the anti-heroine, their grandeur cannot be measured by their acts. Their existence is not dependent on their actions or level of productivity (capitalist, white and masculine)—it is based instead on care and inner life. Their confident poses are a demonstration of the art of sitting as political gesture, calling to mind the implications of the sit-in as well as the denunciation of the segregationist movement and the denial of fundamental human rights. To depict Black bodies in a sitting position in the context of a public space (in a museum, a town square, etc.) is a political statement, as the act of vandalism carried out on a sculpture dated 2022, Seated2 attests.

Beginning in 2021 with the performance Sounding Board, the artist’s practice began to take on elements of the Gesamtkunstwerk, or total artwork. Forays into different mediums—painting, sculpture, engraving, drawing—had heretofore not been organically linked to one another. Self wrote the script, designed all of the set pieces and the costumes for this experimental theatrical piece, which was also eventually made into a film. “From that moment on, I began thinking in terms of creating environments which were completely immersive and I transposed this desire to my painting exhibitions.” Indeed, set design pieces such as tables and chairs which seem to have been taken directly from the paintings can be found in recent exhibitions. Since the works can be used by visitors of the exhibition, they provide a way to come into physical contact with the atmosphere of the paintings, which have materialized in the exhibition space.

Sounding Board, 2021

In 2024 at Art Basel Paris, the same scenographic intentions were behind Self’s My House at the Eva Presenhuber booth, where the works were theatrically displayed across the entirety of the space. The installation features paintings, printed materials, sculptures, art and design objects, all of which project the viewer into a domestic space. Here, Self conjures the historical figure who has been present since the early stages of her practise: the Khoisan woman Saartjie Baartman3, also known as the “Hottentot Venus.” Baartman was reduced to slavery and exhibited across Europe because of her “atypical bodily features”, due to “steatopygia, a hypertrophy of the posterior chain, and macronympha, an elongation of the genital organs4.”

Self’s sculptures take on the traits of previous works (like Negligee, 2023) and suggest a variety of characters called upon by the artist depending on the cultural context for which the works are conceived. In Paris, Tschabalala Self tries to imagine what Baartman’s life might have been like had she been able to live freely, making decisions with regard to her environment and her body instead of having to exhibit herself to the voyeuristic ends of the organizers and spectators of human zoos, as well as other types of colonial ethnographical fairs. My House examines modern day as well as historical perceptions of Black female bodies in the Parisian cultural context, providing Baartman with another type of existence.

French colonialism—which had a direct impact on the history of the artist’s family, who hail from Louisiana—is symbolized by the fleur de lys, or lily flower, which is a reference to the practice of branding, a form of punishment which consisted of the “tattooing” of a symbol with a branding iron onto the bodies of recaptured runaway slaves, and was enforced by the Black laws.

In Sommeil Mielle (2024), fleurs de lys engravings are explicit references to burnt flesh, however Self is also alluding to associations of the symbol with the Virgin Mary. For the artist, to surround her female figures with depictions of lilies is a way of “transmitting an almost spiritual form of respect, in order to treat ordinary women with the same reverence which is usually strictly reserved for the only sacred figure of femininity which exists.”

In the French visual context, the artistic references made by Self include those of Fauvism and the cut-outs of Matisse (who was himself inspired by the Harlem Renaissance cultural movement), however the works of artists such as the French-Americans Niki de Saint Phalle and Louise Bourgeois, with their Nanas and “Femme Maison” also come to mind. A certain tendency toward abstraction is also notable. The entire stand is in fact immersed in a white and yellow checkerboard motif—one which has been present since 2017 in the artist’s works and installations—which can be interpreted through the symbolism of her studio, and refers to the wallpaper of a domestic space. It is “almost used as an abstract gesture, a way of labeling the entire environment as a home.”

In Le Festin (2024), the female figure’s skirt blends in with the wallpaper. Is she disappearing, collapsing, or is she trying to appear, to be reborn within herself?

“In all of the other works, the figure situates itself at different stages of its actualization or becoming. However, in the latter case, the figure almost disintegrates into abstraction. This means that it’s losing its singular identity. In my work. I’ve already talked a lot about the iconographical meaning of Black female bodies and now I’m starting to become more interested in the creation of symbols as opposed to individual characters.”

If Tschabalala Self’s characters manage to liberate themselves from the contradictions that the othering gaze7 has rooted in their existence, it will perhaps be due to this abstract turn. They just might be able to rid themselves at long last of the ultimate constraint which holds back their figure, that which has been imposed by the regime of representation—resemblance.

Notes :

1 All artist quotes date from an interview conducted on 16 October, 2024 at the Eva Presenhuber stand at Art Basel Paris, Grand Palais.

2 Installed in a park in Bexhill-on-Sea, England, this monumental sculpture, which depicts a seated Black woman, was covered in white paint following its

inauguration.

3 b.1789 in South Africa, died in 1815 in Paris.

4 https://memoire-esclavage.org/biographies/sarah-baartman

Head image : Tschabalala Self, My House, vue d’installation / installation view, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Grand Palais, Art Basel Paris, 2024. Photo : Annik Wetter.

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Bharti Kher, Agnieszka Kurant , Shio Kusaka, Jeanne Vicerial,

Related articles

Biennale Son

by Guillaume Lasserre

Lou Masduraud

by Vanessa Morisset

Bharti Kher

by Sarah Matia Pasqualetti