Etienne Bernard & Céline Kopp

Like Ghassan J. Hage, an author whose book Is racism an environmental threat? features prominently in the library of this Ateliers de Rennes – Biennale d’art contemporain, and creates a link between fear of migrants and fear of rubbish, the works we come across in Rennes for the most part make the skilful wager interlinking several of today’s major topical themes, be it in the art world or the world of the more general media: racism, sexism, environmental crisis, capitalism, domination and colonization. Whereby this biennial talks about collectivity but without communitarianism, and lets the works exist without stifling them within a rigid thematic framework. How? Probably because each one of the artists presented talks above all about things that make them suffer, as singular people. The fact is, and this is the wager made by the two curators, Céline Kopp and Etienne Bernard, whom I met on a café terrace in Paris on a particularly warm October day, that this suffering may also be beautiful and terrible when it is shared, like the mythical cry of the singer Abbey Lincoln on Max Roach’s record We Insist:Freedom Now!, which is how our discussion started. First and foremost, there are those cries announced in the event’s title: “À Cris Ouverts”. But who is crying out in Rennes? Is it the artists, or is the whole world screaming?

Céline Kopp: This 6th version of the Ateliers de Rennes is opening ten years after the financial crisis of 2008. The world has changed, faith in the metrics of infinite growth has been shattered. There is the climatic emergency. We wanted to think about the way we are living in the world, from how we exploit resources, and relations of domination, to value-creation systems. Artists haven’t waited until today to raise these questions. For you, is this cry already a scream? There’s a bit of that going on, it’s obvious… But above all, what is a cry?

Etienne Bernard: A cry is a sound which bursts into reality. It’s a breach.

CK: Cries are not peculiar to human beings, by the way. They work beyond grammar, and they’re not always screams or shrieks. A cry can be a cry of joy. There’s the pitch, and the length. This is what Jean-Marc Ballée has managed to create for the graphics of the Biennale.

EB: It can be a cry of pain.

CK: It’s life, in fact. Life starts with a cry.

EB: A cry is also a supreme form of expression.

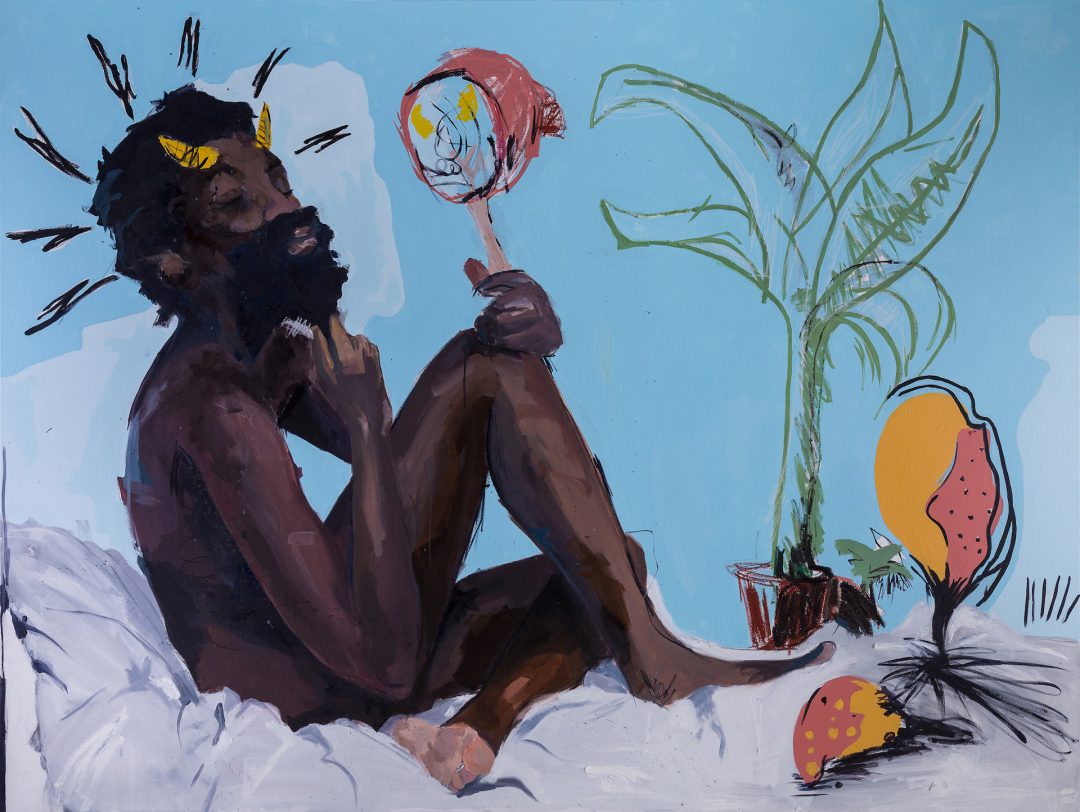

CK: A cry is often thought of in antithesis with language. There’s a “non-educated” aspect, contrasting with mastery of words and labels. Something that can rise up, unregulated and possibly disturbing. A cry, in fact, is the “other” whom one doesn’t control, and that can be frightening. It’s no coincidence that this is a subject for Black Studies, like improvisation. These notions are often racialized, as are the spheres of the unthought-out, the bodily, and disorder. We’re interested in the emancipating capacity and the power of the cry. We’ve listened a lot to Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite, an album that was released at the height of the civil rights struggles in 1960. There’s that cry—Abbey Lincoln’s. She whispers, she groans, weeps and starts to shout. She takes us from the heart of oppression towards an explosion of rage, painful, beautiful, dangerous and powerful, like an orgasm. We’re in the belly of anger. It’s disorienting. Incidentally, her vocal chords were damaged. That cry was very controversial. That freedom and that intensity—even in the suspensions—recur in the works in very different ways: with Senga Nengudi, Paul Maheke, Kudzanai Violet Hwami and Wu Tsang. His video We hold where study is a collaboration with Fred Moten, an author we went to meet. He sums it all up when he writes: It hurts so much that we have to celebrate. That we have to celebrate is what hurts so much.1

It’s a cry that also goes against the grain of artistic conventions?

CK: The theoretical and artistic world of the biennale is very sound-oriented. In In the Break, Moten starts with Frederick Douglass’s description of the cries of his aunt Hester being flogged by her master. He talks about their actual resonance and connects performance and blackness with object and objectification concepts. These texts have worked hand-in-hand with us, because they broach the issue of loss, by pushing thinking about performance as far as the possibility of the object’s resistance… How bodies are able to extract themselves from an imposed writing. Moten invariably comes back to sound: The unthinkable is a tone.2 The beginning of the title is linked to this idea of fugitivity, to those transgressive forms of resistance which fuel the radical black tradition. This rings out in the work of many artists today. We were also keen to show, through a wink at Edouard Glissant3, that these authors owe him a lot.

So who’s crying out?

CK: The artists all together? Even if it’s not literal and the radicalness involved can take on different forms. Like repeated gestures, or silence. There are also those almost invisible forms of resistance. This is quite clear in Mierle Laderman Ukeles’s work.

EB: Mierle Laderman Ukeles wrote the Manifesto for Maintenance in 1969, where she made the point that, as a woman and a mother, she was devoting all her time to household tasks. She declared that, as from that moment, everything she would do would be a form of art reconciling activities of necessity and art itself: ‘maintenance art’. Forty years later, this is still topical.

CK: Precisely, she shows that acts of resistance can be part and parcel of the circumstances of everyday life. On this subject, there’s a wonderful sentence uttered by Tina Campt, which says that daily life is a practice rather than an action. And that this practice is that of the dispossessed, in their struggle for what is possible within day-to-day constraints.4

Which leads us, it just so happens, to my next question: the question about this “we” or “us” which emerges from the writings of Jack Halberstam and Fred Moten. With these authors, we find the idea of grouping a certain number of people together, all of them connected by the fact of having been dispossessed: colonized peoples, queer people, afro people, working-class people. Does your project also draw the outlines of such a collective?

CK: This biennale is permeated by the presences which Fred Moten and Stefano Harney would call ‘the undercommons’. But yes and no, because as soon as you draw outlines to define a group, you confine it. The place for all this exists in the movement, and it’s true that the conversations with Jack Halberstam were important. Especially about the word ‘wildness’, decolonized, which he describes as “everything which resides beyond the current systems of the logic of regulation”.5 The artists we have brought together here all, in their own way, question the dominant vision at work in our society. The one that the anthropologist Ghassan J. Hage calls “generalized domestication”.6

EB: What we can say is that we wanted to introduce a more horizontal logic. We invited the artists to jointly construct the grammar of the event. Yes, we’re in a collective logic, but what best defines it is the fact that it is not locked into any definition. It’s rather a sort of shared, open platform, involving artists and thinkers, but also students and critics…

Can we consider the notion of decolonization as a main theme helping us to understand this biennale?

EB: Let’s say that the question of post-colonial studies, in France, is something that is at once being very worked on, and not worked on much at all, in relation to the Anglo-Saxon context. Taking the notion of decolonization in a French context as a main theme would also be like putting a frame around it. It would have been necessary to write the history of that de-colonization in France, and that isn’t what this show is about.

CK: Decolonization is not dealt with as a subject illustrated by artworks. This must become a practice in our professional field. We’ve been careful not to repeat hegemonic mechanisms, and habits. We’ve thought about addressing the other. In other respects, the fact that a list of less masculine and white artists is unusual… That says a whole lot.

EB: To put it crudely, a biennale is seen or regarded as a place of power. We’ve tried not to think like that. We’re showing bodies of more important work for each artist; we’ve refused to define them by their nationality…

CK: We’ve tried to create a dialogue. Six months before the opening, we brought together those taking part to look for a common vocabulary.

How did you work to arrange those encounters?

CK: Instead of being a letter of intent, we wrote a new year’s letter. The year 2017 was the most prosperous ever recorded by economic indicators, despite the conflicts and crises… We suggested bringing together the artists, the local teams and crews, authors, researchers, and performers… The idea being to create a ‘safe space’ without it being public or recorded. Everyone contributed the way they wanted to. Madison Bycroft, Julien Creuzet and Jean Charles de Quillacq all put on performances.

Do some of the productions for the biennale still show traces of it?

CK: It enabled us to raise real questions, especially about the economics of presence, mobility and production. Some artists didn’t come, out of choice, or because it wasn’t possible. Raymond Boisjoly, an artist with Haida ancestry (from Alaska), decided to take part from Vancouver, and that distance lay at the centre of his contributions. Jessie Darling didn’t come, because she was in a physical situation which restricted her mobility. K.V. Hwami, born in Zimbabwe, was waiting for her British residence permit to be renewed. Conversely, Erika Vogt thought that the show was important, but for ecological reasons, above all, she didn’t want her works to be transported. She herself came to the biennale to produce work on the spot. All this helped us to be aware of our choices.

In Sondra Perry’s video installation, we see her visiting the British Museum with her twin brother, who stopped at an Egyptian temple and exclaimed: “You mean to say that they dismantled this thing brick by brick and made it travel across the world to put it here? That’s totally fucked!” It’s seemed to me that some of the works carried within them this form of irreverence in their way of handling the artistic and cultural references, a “dovetailing” of identities, which happens, but in an unconventional way, with a form of joy and levity?

CK: She shows with a great deal of intelligence that the mechanisms of relinquishment are always at work. Her brother played basketball in a university team, and the whole team had its identity stolen by a video game. There was a trial. Sondra Perry traces a continuity between the confiscations of works to be found in the collections of western museums, the story of her brother, and the way in which technology goes on misusing visible minorities. The chroma key blue that’s in the video and on the walls of the installation is a blue that denies bodies. It makes it possible to bypass them and embed them in other contexts.

To wind things up, I’d like to ask you a question about optimism. It’s seemed to me that, in certain projects in particular, and especially in Meriem Bennani’s installation comparing two generations of aïta singers, but also in Sonia Boyce’s project involving students squatting the Museum of Fine Arts, and in the paintings of Kudzanai Violet Hwami, there was a sort of tenfold energy, a rather enjoyable sense of freedom, possibly connected with this position that you describe as being “in the cracks of the system”?

CK: This is precisely what the idea of fugitivity introduces in relation to afro-pessimism. The improvisation of alternatives. With Meriem Bennani’s work, we can clearly see the power of oralness, which makes it possible to hang on to this levity while dealing with hard issues at the same time.

EB: There’s also the desire to go towards the productive. Plato talked about this in The Republic. It’s through taking into account the organized system, and using it, that one attains freedom, and can make poetry. It’s when one understands the system that one understands its cracks, that one finds areas of tension which one can make even tenser, or less tense. I don’t know if this is necessarily optimism, but in any event it helps one to do things.

CK: I can also see Kenzi Shiokava’s smile, aged 80, and his work with its mind-blowing energy. Let’s end by talking about generosity: thanks to all the artists and authors… They are the voices of this biennale.

- In Fred Moten, Black and Blur, Durham, Duke University Press, 2017.

- In Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of A Black Radical Tradition, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2003.

- “La pensée du tremblement surgit de partout, musiques et formes suggérées par les peuples. Musiques douces et lentes, lourdes et battantes. Beautés à cri ouvert. Elle nous préserve des pensées de système et des systèmes de pensée…” [Thinking about trembling emerges from everywhere, music and forms suggested by peoples. Slow and gentle music, or heavy and rhythmic. Beauties with open cry. It preserves us from thinking about systems and from systems of thinking …”] in Edouard Glissant, La Cohée du lamentin, Paris, Gallimard, 2005.

- “The quotidian must be understood as a practice rather than an act or an action. It is a practice owned by the dispossessed in the struggle to create possibility within the constraint of everyday life”. Tina Campt, “Black Feminist Futures and the Practice of Fugitivity”, a lecture given at the Barnard Center for Research on Women, 7 October 2014. http://bcrw.barnard.edu/videos/tina-campt-black-feminist-futures-and-the-practice-of-fugitivity/

- Jack Halberstam, “Wildness, Loss, Death”, in Social Text 121, Duke University Press, winter 2014.

6 Ghassan J. Hage, Is racism an environmental threat?,Chicester,Wiley, 2017.

Image on top: Kenzi Shiokava, musée des Beaux-Arts de Rennes, for « À Cris Ouverts ». Photo : Aurélien Mole.

Related articles

Céline Poulin

by Andréanne Béguin

Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Interview with Warren Neidich

by Yves Citton