Nicolas Bourriaud

Late January saw the launch of MoCo which stands for Montpellier Contemporain. As the first stage of the project supervised by the curator Nicolas Bourriaud, the art centre La Panacée, formerly dedicated to digital cultures, welcomed the first exhibitions of its new programme. Three focal points—a group show, “Retour sur Mulholland Drive” ; a selection of works around the theme of employment, and a solo show for the young artist Tala Madani—in whose concomitance could already be read the direction being taken by the project as a whole—planned for completion in 2019 with a “collectionless museum” and a close partnership with the School of Fine Arts and the university—namely, the desire to ramify on the scale of the entire metropolis an artistic programme designed to re-position the south of France on the map of contemporary art. And in so doing, take cognizance of the situation of a globalized art world whose forms, logically enough, can only be understood in their plurality.

The Montpellier project is innovative because it immediately plays the card of subdivisions. Rather than a single statement-building, the MoCo is a three-headed hydra, consisting of the La Panacée art centre, a “collectionless museum” which will open its doors in the Montcalm mansion in 2019, and the School of Fine Arts. Likewise, at La Panacée which inaugurated its first exhibition cycle in late January, the programming is tripartite. Why did you opt for this poly-perspectival approach?

The commission made to me by the mayor of Montpellier, Philippe Saurel, consisted first of all in building an original institution and offering an artistic itinerary in the city. In the end, all I had to do was link these two requests together, knowing that what people wanted to avoid was a project of the Bilbao Guggenheim type. The time for that sort of intimidating logo-edifice seems over, to me. The idea was to incorporate this project within Montpellier’s urban fabric, espouse the city’s form and reflect its energy by renovating existing buildings. The three sites form a kind of triangle encompassing the downtown area. The project involves creating a functional complementarity, from training/education to exhibitions, by way of residencies, publishing, research and production. Why? Because contemporary art is not solely an object of expression, because challenges to do with knowledge, sociality, and education are also part of it. As far as the La Panacée programme is concerned, it is first of all split into three parts so as to comply with the architecture of the place, which does not make it possible to house an exhibition all in one block. I’ve preferred to play with the long ambulatory which the exhibition rooms give onto. In other respects, I have a certain soft spot for “short formats”, as opposed to those long-drawn-out shows, or exhibitions desperately trying to be comprehensive. It’s better to be succinct than talkative, or desperately looking for exhaustiveness. The programming for La Panacée, at least until 2019, will thus operate like a kaleidoscope of the mood of the times, with these smaller formats enabling me to look in more directions, and pinpoint more avenues.

Jonathas De Andrade, Zumbi encarnado, 2014. Fundacion Helga de Alvear, Caceres. La Panacée, “Retour sur Mulholland Drive”, 2017.

You’re keen to see an alternative scene in the south of France which would take up a stance in relation to Paris, the way Los Angeles has done in relation to New York. We know about the dynamism of Marseille, which is currently attracting lots of young artists fresh out of schools of Fine Arts, after playing host to a thriving scene in the 1990s, in particular around the gallery owner Roger Pailhas and the MAC, which has seen a succession of directors including Bernard Blistène, Philippe Vergne and Nathalie Ergino. What is that hallmarks the art scene in this “other south” called Montpellier?

In our heads France is Paris plus this huge half-wild territory which we call “the provinces”. This is colonial imagination stuff: the term, incidentally, comes from the Roman Empire; above all, though, it’s old-fashioned and insidious. In diplomatic language, people are now talking about “regions”: but as far as I know, Paris is also a city situated in a region, so the word means nothing… The Jacobin ideology is part and parcel of the language. This colonial-type centralization, so deep-rooted in French mentalities since Louis xiv, means that there is no real rivalry, no cultural polarity: this contributes to the national anaemia. Because, all of a sudden, there’s no tension, even though all polarization is advantageous, like Madrid/Barcelona, or New York/Los Angeles… And because France is historically North/South structured, langue d’oïl/langue d’oc, it is necessary to get this tension to exist, and give it clout. Bernard Blistène’s experience in Marseille, which I experienced at close quarters in the 1990s, has been a source of inspiration for this Montpellier project. All the more so because that moment has been and gone, because the city no longer has the same dynamism today: everything in it relies on artists and individual initiatives, here, there and everywhere. In Montpellier, on the other hand, there is team work. Historically speaking, it’s an irredentist, dissident city, on account of its Cathar past, the fact that it was part of the kingdom of Aragon, and its university founded in the 13th century. It also enjoys 300 days of sun a year, it’s a metropolis that extends from the mountains to the sea. Over and above its palm trees, it’s this horizontality which made me think straightaway of Los Angeles. But what is permitting the emergence of such an ambitious project is above all the existence of a political will. I do not however believe in an identity which would be a southern “essence”; the south has to be re-invented, a 21st century south, a Mediterranean of today.

How is this wager being expressed on a local scale, with a globalized art world from which it seems hard to extricate yourself, a world that has become as much context as infrastructure? Otherwise put, should we see in the wish to so closely associate art school and art centre —a not very common model in France, with the exception of the Villa Arson in Nice— a desire to create a super-breeding ground for young artists, who will then be summoned to go into orbit in the international network, or do you think that a more all-encompassing model might be possible?

It’s precisely because the art world is more and more globalized that a single city cannot suffice, either to make the French scene exist, or as a magnet of international attraction. Let’s take a look at the best French art centres, let’s take the Consortium in Dijon as an example: it’s not sufficiently surrounded by infrastructures on a par with it. And even if, incidentally, it gives rise to many projects in its region, we’re still this side of that threshold which makes it possible to carry on a “scene”. The idea of coordinating a museum, an art centre and an art school will enable Montpellier to become a force of training and practice, all of whose components will be heading in the same direction, with one and the same ambition, but with eclectic viewpoints. The difference with the Villa Arson in Nice is that these sites are distinct from one another, while the Villa is a school in which there is an art centre, or vice versa. The Montpellier Contemporain (MoCo) project is being constructed on the scale of a metropolis, it’s inseparable from its overall cultural policy. But the most important pointer, to my eye, is the fact that the graduates of an art school should stay in the region after their studies, and this means having an infrastructure. We are also nursing the project of setting up a post-graduate programme, a bit on the model of the Pavillon at the Palais de Tokyo, which has just closed. In other respects, the student residency with 60 rooms, located at La Panacée and jointly run with the CROUS [Centre Régional des Œuvres Universitaires et Scolaires], offers us other prospects.

We’re poised on a year with lots of biennials and other events summoning an international population lured by a promise of things local. In your view, what do these events contribute?

As events, not necessarily a great deal. We’re in a world of cultural tourism. But as exhibitions, they contribute what their content brings us. If we take the Kassel documenta, it’s always been a moment of taking sides and “taking a break”, like a freeze frame over the past five years. In 2002, with Enwezor, it was the high point of the documentarist momentum in art. In 2007, Buergel focused on a historian, not to say antiquarian model. In 2012, politics got the upper hand again, but, to my taste, in a not very clear way. In a nutshell, this is the moment to take a stance. And if there isn’t a stance, biennials in effect will represent nothing more than animation. There remains this “promise of things local” which you’ve mentioned, which mustn’t be overlooked either.

“Lighting by beams”, those were the words you used to explain the concomitance of several exhibitions, responding, in your view, to the situation of an “art world marked by hyper-production and the proliferation of signs”, in which it would be futile to postulate any kind of essence of art of the moment, and even more so to try and flatten out the specific features within a movement. How did you reach this conclusion?

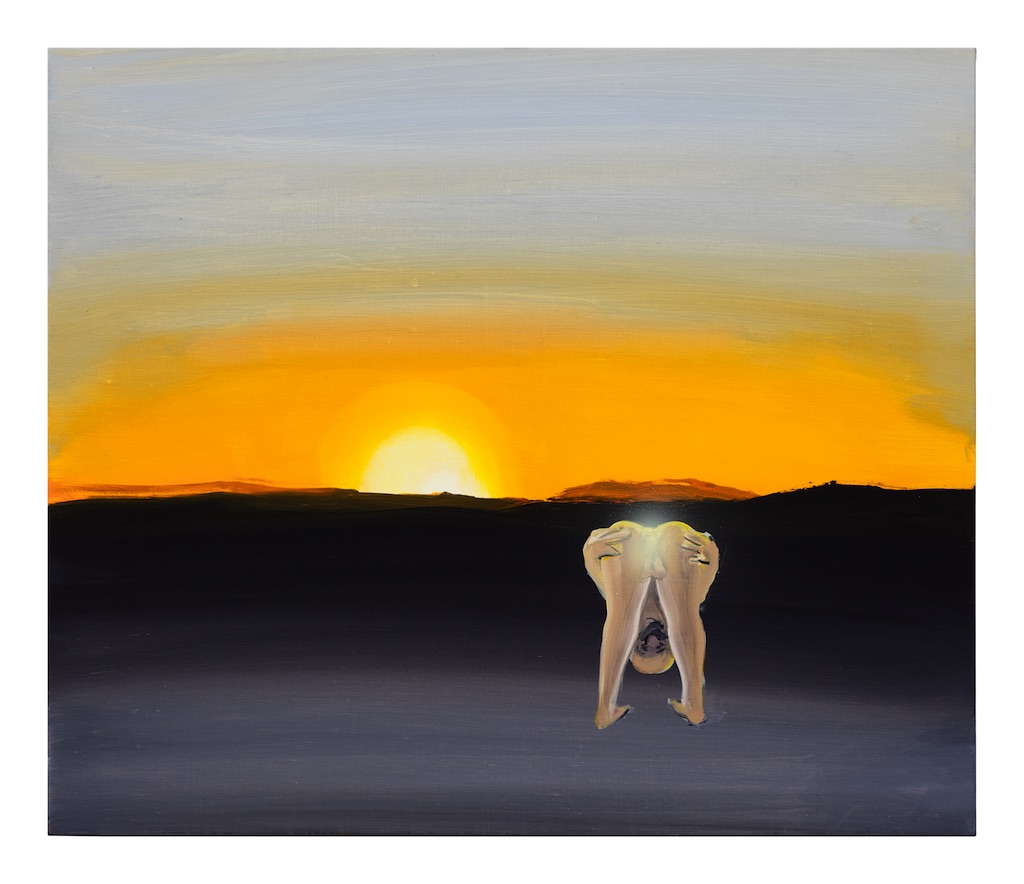

In the late 1990s, I’d developed the concept of the “semionaut-artist”. From semios meaning sign, and nautos meaning navigation. The arrival of the Internet then created a mental space favourable to new artistic practices, whose common denominator was the creation of meaningful itineraries within a host –or cloud–of data: the artist links together signs that are distant in time and space. So, in a way, this proliferation of signs also gives rise to “movements” and aesthetic decisions. But there is a real crisis of formal thinking which means that criticism is focused on large masses, on blocks of visibility, to the detriment of a more subtle analysis of visual movements, and of events which affect the way artists have of perceiving the world. In my view, why is it necessary to learn to look at several things at once in order to understand “what’s going on”? Because “what’s going on” is always “between” things. Real aesthetic events end up by becoming crystallized in works with a manifesto value, but they are presented in interstices, linking forms together. At La Panacée we thus have three exhibitions, three different lights… Incidentally, rather precise light spots are known as “brushes”. We’re reaching a moment in history when the media are not enough to define praxes, they are no longer mutually exclusive. It’s trajectories of thought that interest me, it doesn’t much matter about the nature of the materials that the artist uses. Between the painting of Tala Madani, an exhibition about job offers in art, and a visual essay about a David Lynch movie, there is on the face of it no connection. To my eye, however, these are three statements about the current situation.

In the face of this “hubbub” which Lionel Ruffel also talks about, extending your formulated observation on the scale of the art scene to being in the actual contemporary world, where do we identify the common base which makes it possible to create, if not movements, then at least ephemeral communities brought together for the time-frame of a show? The exhibition “Retour sur Mulholland Drive” seemed to suggest the track of shared imagination, of a community welded together by its narratives and myths…

These “shared imaginations” are nevertheless increasingly fragmentary. The issue of ephemeral communities already lay at the heart of the relational aesthetics that corresponded to this sense of a loss of sociality, to the disappearance of common bases. Today, these latter are being replaced by passwords: the theme of “Retour sur Mulholland Drive”, which takes Lynch’s film as its material, is probably that of the sign as password, or clue. Art history is one of the last bases from which it’s possible to envisage writing a common history. If we lose that reference, there’ll be nothing except the market like a public baths. Whence the importance of historicization: the historical narrative is the only one suitable for underwriting something contemporary, for guarding us against a version of things contemporary as handed over to the arbitrariness of commercial interests. Without historical discourse about the current situation, without words which may describe the strong points of our present state, and which derive prospects from it, we would be at the mercy of the volatile discourse of marketing. We have to stand up to the illusion that “there’s nothing to be seen in it”, that we are navigating as far as we can see, in the fog. Being a curator, nowadays, means striving to discern forms and ideas in the mists of our day and age.

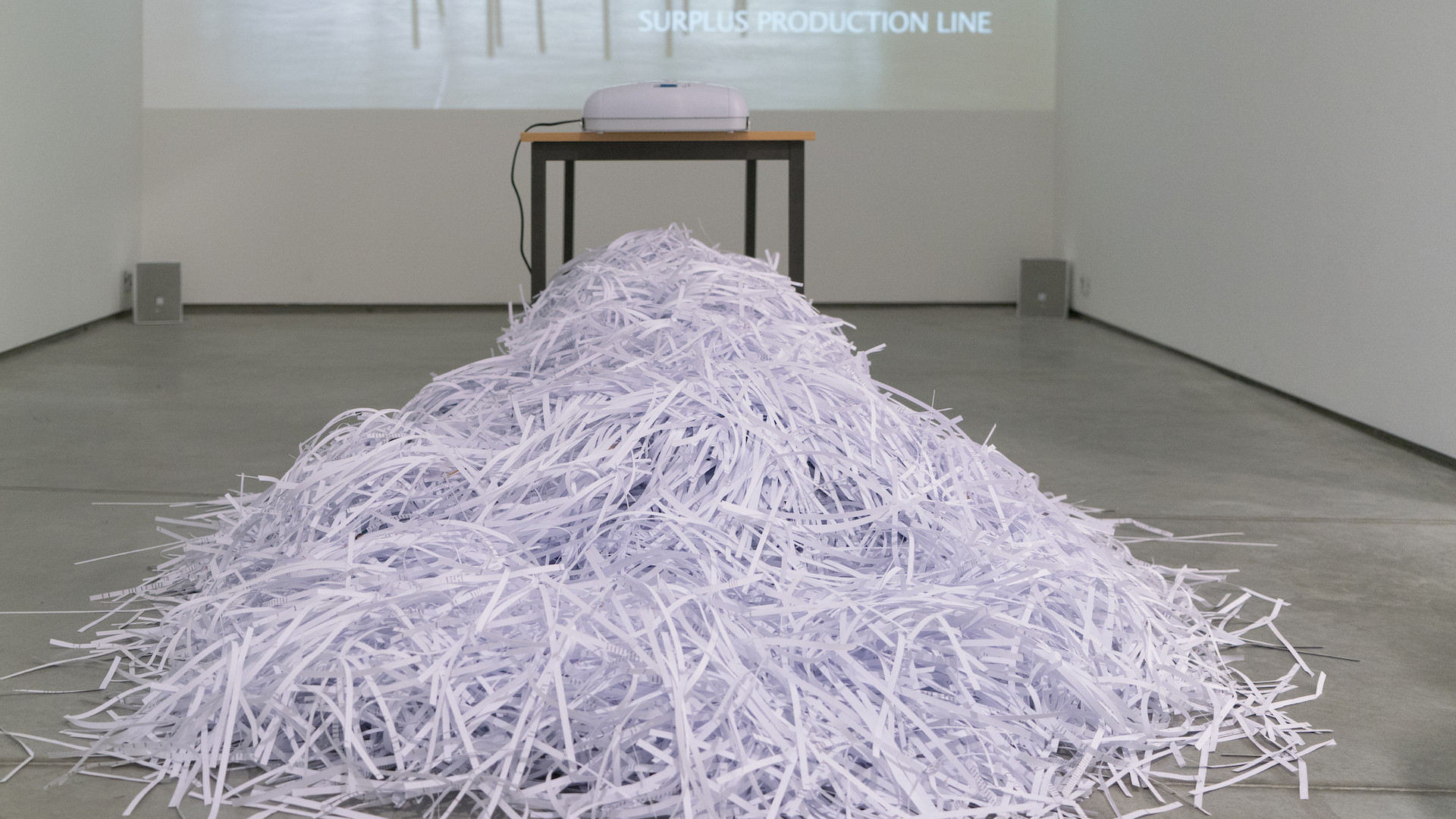

(Image on top: Adrian Melis, Surplus Production Line. Courtesy Adrian Melis.)

- From the issue: 81

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion, Hoël Duret, CLEARING, Hanne Lippard, Mark Alizart,

Related articles

Céline Poulin

by Andréanne Béguin

Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Interview with Warren Neidich

by Yves Citton