Bouchra Khalili

How can one not topple over into aestheticizing the struggle? How can one not serve as an alibi and mantle for the realities of the racialization, segregation and dross of a latent colonialism which is still working its way into all the layers of our western societies?

The issues raised by the Bouchra Khalili exhibition in Paris are questions which result from the hiatus between art and politics and the eternal risk of betraying the struggle and treating it euphemistically—or rather, struggles, plural, for the emancipation of peoples and people. Well before the impressive media output that came in its wake, The Mapping Journey Project already announced both the absurdity and the dramatic nature of wandering through a Europe endowed with human rights for people unlucky enough not to be born in the right place. Ten years have elapsed since the masterly and straightforward Mapping, ten years during which this same radical vein has given rise to a series of films linking up with an anti-colonialist and anti-segregationist tradition which, as a counterpoint to this wind of revolt, reveals our indifference and selfishness, at the same time as it questions the position of the artist, called upon more than ever to revitalize and rethink the figure of the witness, a figure such as Jean Genet who haunts the artist’s latest work, Twenty-Two Hours, with his inveighing against our policed and police societies. If Bouchra Khalili’s œuvre is at times nothing less than scathing, this is because what is involved is not letting oneself be lulled by the gentleness of projections which, once back amid the hurdy-gurdy of social life and fashionable gatherings, run the risk of being watered down in the comfort of our protected lives. Not that it is a matter of making the visitor feel guilty but, as such as Pasolini, Godard and Marker well knew how to do it, creating a real “politics of the eye” by way of viewing systems in which powerful images circulate which have a lasting effect on our retinas and, beyond our retinas, our consciences, by continuing to circulate beyond the, when all is said and done, restricted forums represented by art centres and auteur film festivals.

Bouchra Khalili, The Tempest Society, 2017.

Video 2K, 60’. Original languages: Greek, Arabic, Levantine Arabic (Syrian), French. Produced for documenta 14. Co-produced Ibsen Awards, with the support of FNAG, Paris ; Holland Festival, Amsterdam. Courtesy Bouchra Khalili.

Viewing the large number of videos you are screening at the Jeu de Paume, what emerges is a sort of indirect homage to those great film directors you highlight, the Godards, Pasolinis and Markers, who appear as emblematic figures to whom the cinema of the 1950s and 1960s could still offer a chance to express their revolt: that cinema now seems quite moribund, as Serge Daney observed back in the 1980s. Do you think that contemporary art can re-kindle the flame of that politically engaged art, while nevertheless remaining aware that, unlike film, contemporary art touches an infinitely smaller public, and concerns a cultivated, captive elite? Is it not indirectly the possibility of a popular art that is posited through this barely veiled nostalgia for that vanished cinema?

I wouldn’t use the word homage, and even less nostalgia; I’d rather talk about crossroads taking shape. If there’s a Pasolini image that lasts for a few minutes in The Tempest Society (60’, 2017), this is obviously because of the admiration I have for him, but above all because he came up with theories about this notion that I’m so fond of, the notion of the ‘civic poet’, which defines the members of the Al Assifa1 troupe who are the film’s starting point, as well as all the people who appear subsequently. It so happens that I’m extremely interested in a tradition that’s dying out in Morocco, the Halka, the art of the storyteller, so-named after the circle formed by the people listening—Al Halka meaning circle in Arabic. The first time I came across the notion of civic poet in a Pasolini text, I instantly thought about the Halka: the storyteller who takes over the public place to tell a tale which mixes vernacular and highbrow languages, and popular tales and classical poetry, to tell people’s stories and talk about their present state to those whose words have no public existence. It so happens that the Halka greatly influenced the members of Al Assifa for their performances, insomuch as several members of the troupe were Moroccan. Furthermore, The Tempest Society is set in Athens, with the film dealing equally with the birth place of the public word and its historical link with the birth of the notion of the “citizen” as a political subject. So this presence of Pasolini was not haphazard, but stemmed from the connection between a certain relation to the filmed word and representation, self-performance as both citizen and subject.

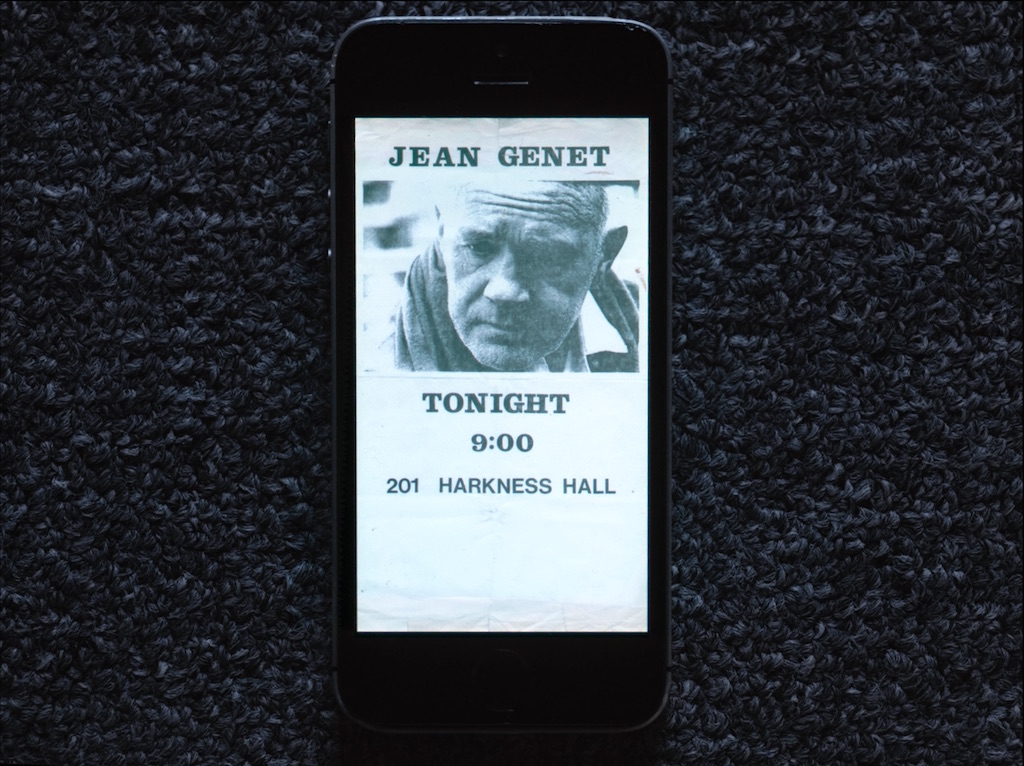

Likewise, the presence of Godard in Twenty-Two Hours (43’, 2018) is connected with the narrative by Quiana, Vanessa and Doug2 dealing with the presence of Jean Genet among the Black Panthers. While working on Genet’s stay in the United States for this film, I discovered that Godard and he were at Yale at the same time, Godard just returning from a Palestinian camp in Jordan, where Genet would go some months later. I found the coincidence surprising and I couldn’t just leave it at that. Whence the appearance of Godard in a short sequence which sets up the relation between “here and elsewhere”, linking Genet’s presence among the Black Panthers, and then among the Palestinians a few months later. It’s the reverse itinerary to Godard’s who, during his stay on the other side of the Atlantic, would also support the Black Panther Party with calls for solidarity and articles for the party’s paper. That “encounter” between Genet and Godard also enabled me to recall the films of the Dziga Vertov period and that conception of the film as “blackboards”, which everyone can appropriate individually and/or collectively to write their narrative, so that it can travel and be of use to others. I’ve obviously thought back to several of my films where people write and draw on flat surfaces, sometimes quite literally on blackboards. This became the title of the exhibition at the Jeu de Paume which, in a way, makes it possible to weave a link between the performance, the written word, the spoken word, what is filmed, the inscribed trace, and their movements, including in space.

Otherwise put, it made it possible to ask the question: can an exhibition space be a civic space, including in the poetic sense, the way the space of the Halka has been for me, for example?

And in your question there’s another one: how are we to connect the public with so-called elitist activities? This question is as old as the history of art as an area of knowledge. It also haunts the history of film. With one exception: Hollywood in the classical period when the avant-garde managed to be popular, thanks to strategies with a hitherto unheard-of sophistication. It was perhaps the death of that particular cinema that Daney was lamenting, and which Godard has forever paid tribute to: how to re-find the lost secret of that golden age? For my part, I feel no nostalgia for it, because the films are still there, they remain our contemporaries, provided that we show them, and people are still making superb films within the cinema, but also in art. It’s precisely for this reason that I helped found the Tangier film centre more than ten years ago: we did that for both the present and the future, thoroughly aware that, in a country where cinemas are closing one after the other, and where there is no public (thus free) film school, there was a pressing need to create a place where films can be shown and where young videomakers and filmmakers can meet, see films, show their own films, and use the facilities. So I’m an optimist who has chosen the arena of art precisely because, in terms of power, it’s a horizontal space, a civic space.

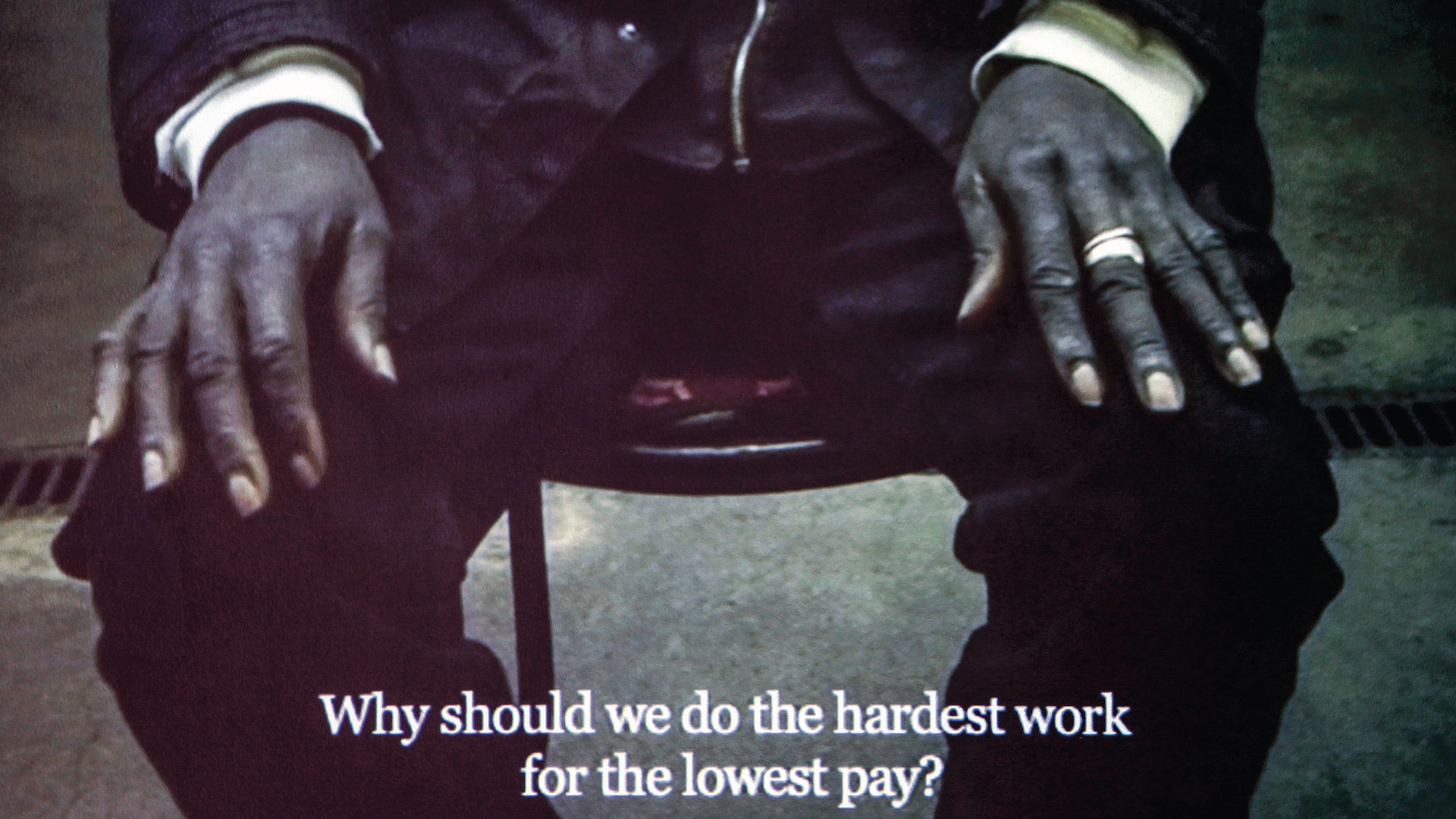

Bouchra Khalili, Twenty-Two Hours, 2018.

Video 4K, 43’. Original languages: English, French. Produced for Ruhrtriennale,

with the support of Oslo National Art Academy ; Harvard Film Study Center ; Secession, Vienne. Courtesy Bouchra Khalili.

In the essay you’re publishing in the catalogue for the Jeu de Paume show, you mention the figure of the “witness” who, for you, is fundamental, with, obviously enough, in the “title” role, Jean Genet who remains a (peerless) model, a witness who is not content with being a passive observer but who takes on the function in nothing less than a political commitment in which the whole scope of his talent as a poet is developed (commitment serving as a driving force for poetry, and vice versa). Do you think that a figure like him still exists? Wasn’t that figure associated with the powers (of subversion) of literature, which have perhaps disappeared today?

The figure of the witness is in fact important in my work, but it’s developed with that of the civic poet as a form of shift, so as to raise again and again the same question: when someone speaks, who is speaking and, above all, what is being “spoken” through that voice?

From this viewpoint, Genet is in effect an almost synthetic figure: a poet who gave up writing to become a sort of radical ally. He didn’t speak for the Black Panthers, he spoke in the terms that the Panthers deemed most useful for their cause. Incidentally, he said as much quite openly to an American journalist in a filmed interview that you can see in Twenty-Two Hours, when she asks him what he’s come to do in the United States, he answers: “I’ve come to bear witness to what I’ve seen, about the injustice and racism which exist here in the United States”.

Later, in my film, we see Quiana and Vanessa going back over Genet’s appearance during the 1970 May Day rally at Yale. He is there to address the crowd, but it’s not he who reads out his speech, it’s Big Man Howard who does so in front of the thousands of people occupying the university. Big Man was an important member of the Black Panther Party and a friend and comrade of Doug Miranda. In the previous sequence, Doug explains how he undertook his militant work at Yale and managed to mobilize most of the campus. So the witness question becomes more complicated. There’s Genet who defines himself as a witness. There’s Doug whom we can identify as a witness and who talks about his encounter with Genet, his own involvement in the party and his work as an activist. And there’s Quiana and Vanessa who take charge of the narrative in all its different dimensions.

Quiana and Vanessa raise the question that introduces the film’s final part: who is the witness? Is it the person who can still speak? Is it the person whom books speak about for him, beyond death? Or is it the person who speaks when nobody else is there to speak?

Then Doug appears with the two young women who ask him about the Black Panther Party’s legacy, but Doug doesn’t get into the party’s legend, he says that the party foundered but that the struggle goes on. In other words, he doesn’t talk about the past as much as the future. And this is perhaps the witness, in my work, in any event: the person who speaks about what is still to come. So, from this viewpoint, the witnesses in reality are Quiana and Vanessa.

Are there Genet-like figures today in the field of literature? History doesn’t repeat itself, so the question, for me, doesn’t apply. And I’d be more optimistic than you in saying that there are numerous witnesses and they are not necessarily to be looked for in the literary and cultural arena. They are there, all around us. All we have to do is lend them an ear.

Bouchra Khalili, Twenty-Two Hours, 2018.

Video 4K, 43’. Original languages: English, French. Produced for Ruhrtriennale, with the support of Oslo National Art Academy ; Harvard Film Study Center ; Secession, Vienne. Courtesy Bouchra Khalili.

I’d like to go back to that extraordinary anticipation (prophetization?) that you showed in the Mappings series: “This work, it should be noted, was completed several years before a whole string of later media contributions” as Elisabeth Lebovici phrases it so aptly (in the Blackboard catalogue).3 Although much comment has already been made about those videos, I’d like to emphasize that it’s rare for the absurdity of such situations to be pinpointed which such clarity, over and above their dramatic aspect, which is often underscored and which, incidentally, there is no question of downplaying: in those videos there’s a Buster Keaton-like dimension, people who are victims of futile suffering, and who remain thoroughly stoical, fighting against their suffering with the simple power of their dignity. At the same time, these witnesses turn their back on us and teach us a lesson, a bit like a teacher writing on a blackboard (that thing, again): don’t you think there may be a new way of writing geography at play here, no longer by the “victors” but by the humble, the victims, a reverse geography, redrawing maps, flows and boundaries, based on new factors and methods—an “alter-reality”?

I was a teenager when the Schengen Agreement was signed, but I remember its effects very clearly in Morocco. People often forget, but the abolition of borders for European citizens inside the EU meant, for Europe’s African neighbours, the introduction of visa regulations for travelling in Europe. In Morocco, up to the 1990s, getting a passport was a privilege. With Schengen, the visa privilege was added to the passport privilege. All of a sudden, the gates to Europe were closed with a double turn of the key for all Europe’s neighbours. And as a consequence, the gates to African countries were closed to their own nationals. So what I remember is the obsession about leaving home, which seized all Moroccan young people. The reason: those young people were not treated like citizens in their own land, which offered them no job or other prospects. Those young people didn’t set off in search of some Eldorado but rather just a place to live in as citizens like everyone else. You will note that most of the videos in this installation end with “I want to live like everyone else”, meaning “like people who have rights”.

The stories we hear in Mappings are those which I grew up with. And, as a French-Moroccan, I can also see a historical continuum: would several generations have been forced into exile if the independence struggles had not been suppressed by governments that swiftly became authoritarian?

If this work might seem to echo current goings-on in a particular way, this is possibly because it reflects the contemporary face of western nations, incapable of thinking up any kind of citizenship outside the framework of the nation-state with its borders erected like fences, and whose nationality, as the framework of citizenship, represents the final bolt. This is why I refuse to talk about “refugee crises”, and all the more so because the great majority of Syrians who’ve fled the war are now in Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey. What I see is a crisis of the western nation-state which is becoming less and less democratic, to the point of flouting its own laws about asylum and residence. So we mustn’t be surprised if overtly racist leaders are being elected here, there and everywhere in Europe, and if their rhetoric is being quietly taken up by other leaders, who are nevertheless daring to present themselves as a bulwark against the far right. The witch-hunt against citizens without the “right” papers and the criminalization of those coming to their aid is, in this respect, symptomatic.

The issue raised by this work, if you take a close look at it, is thus simple; why has an unalienable right, like that of freedom of movement, been elevated to the rank of a privilege? Because the model of the western nation-state with its heavy liabilities and colonial continuum proceeds by way of exclusion, in order to define citizen membership.

This is why I never talk about this work by bringing in terms like “migrants” and “refugees”: for me, they are citizens who’ve been stripped of their rights. This isn’t a humanitarian issue, but a political matter which, on the aesthetic level, can be formulated thus: up to what point are we ready to look at the person deprived of his rights as a peer? And if these narratives are recited with calm and precision, this is precisely because the people on whom the narratives are based are presented as people standing up to arbitrariness. They are political subjects who also have a “right to opaqueness” as Glissant put it. A right which the surveillance system of our societies, just like the media system, denies them. This is why faces don’t appear in these films. These people in fact turn their backs on us, but they do have something to show us: the “histories” and the geography they draw and perform implicitly present another map of the world, where history and geography are not the product of domination but acts of resistance produced by those deprived of all their rights. “Blackboards” or education on the sidelines: this is what creates the link between The Mapping Journey Project and the ensuing projects, all those works that can be understood as a meditation on equality, equality before the right of freedom of movement, civic equality, equality with regard to representation, and equality in relations.

Bouchra Khalili, The Mapping Journey Project, 2008-2011.

Video installation, 8 videoprojections, 4:3, color, sound, variable durations and dimensions. Courtesy Bouchra Khalili ; galerie Polaris, Paris.

Do you get the feeling, with this show, of having managed to thwart the phenomenon of “re-orientalization”, of “alibization” of the ‘dark-skinned’ artist , whom Nacira Guénif-Souilamas talks about, who, in her book, needs to “to make the demonstration of it an act of resistance in itself and thus break the codes of exhibition visiting.”4 Doesn’t exhibiting in an institution as hallowed as the Jeu de Paume tone down, in advance, any attempt to remove the aesthetics from a praxis in order to turn it into a quasi-political act?

Nacira Guénif-Souilamas writes as a sociologist and an anthropologist who analyzes situations from a systemic angle. The excerpt from her essay that you’re quoting defines my praxis in these terms in an exhibition context. From my stance as an artist, I would couch the question like this: how are we to turn an exhibition into a place where a community of equals gathers? This is how we may conceive of the exhibition space as a civic space. At this juncture, I must thank Marta Gili who, in terms of dialogue and trust, gave me carte blanche for the hanging. When she invited me in 2016 to show my work, I said yes without a moment’s hesitation, because of the admiration I have for her programming, which often veers away from the beaten track and shows artists who are little seen in France.

Despite the presence of fifteen video works, all the spaces are open. The exhibition works like a constellation that you can take any way you like, thus making it possible to highlight the links between the works, beyond the lens of chronology. So there is an invitation to visitors to move about and concentrate because what interests me above all else is the “politics of the eye”, to wit, the space earmarked for the viewer as subject. A place where questions are phrased and articulated, questions which may at times seem complex. But my viewers are patient. And I trust them. I can understand that people might say about this show that it calls for both time and involvement, but, in my opinion, what it calls for above all is looking at “the other”, the people who are “represented” in my work, as equals. So a space can be opened up for encounters on an equal footing, including in the institutional space, which can also be a space of beauty and, hopefully, poetry.

Bouchra Khalili, Foreign Office, 2015.

Video HD, 22′. Original languages: Algerian Arabic, Kabylian. Produced for Sam Art Prize 2014. Courtesy Bouchra Khalili.

1 Al Assifa was an agit-prop theatre troupe which was active in Paris between 1972 and 1978. It was made up of North African immigrant workers and French students. Their plays, based on experiences undergone by the troupe’s members, railed against the working and living conditions of immigrant works, and called for solidarity between immigrant and French workers.

2 Quiana and Vanessa are the two young protagonists of Twenty-Two Hours. Like all the protagonists in my works, they are not actresses, they are young women involved in movements struggling for equality, led by members of Boston’s African-American community. Doug Miranda was an important member of the Black Panther Party (BPP). First a captain in the Boston chapter, he then became a member of the national leadership. In 1970, as he explains in the film, the leadership gave him the job of organizing the campaign to free Bobby Seale, chairman of the BPP and behind bars in New Haven. Doug would take care of Genet during his visit to the East Coast, organizing his public appearances, the first of which took place in Boston, precisely where Twenty-Two Hours was filmed. Doug was also one of the brains behind the 1970 occupation of Yale University, which climaxed with the May Day Rally. That episode is recounted in my film.

3 Élisabeth Lebovici, “Radical equality”, Blackboard, exhibition catalogue, Jeu de Paume, 2018, p. 70.

4 Nacira Guénif-Souilamas, “Standing still looking over the artist’s shoulder”, op cit., p. 120.

(Image on top: Bouchra Khalili, Speeches – Chapter 1: Mother Tongue, 2012.

Video. Courtesy Bouchra Khalili ; Galerie Polaris, Paris. © Bouchra Khalili / ADAGP, Paris, 2018)

- From the issue: 87

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Claire Le Restif, Sophie Legrandjacques, Sophie Lévy, Christine Macel, Wilfried Huet / GAGARIN,

Related articles

Céline Poulin

by Andréanne Béguin

Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Interview with Warren Neidich

by Yves Citton