Claire Fontaine

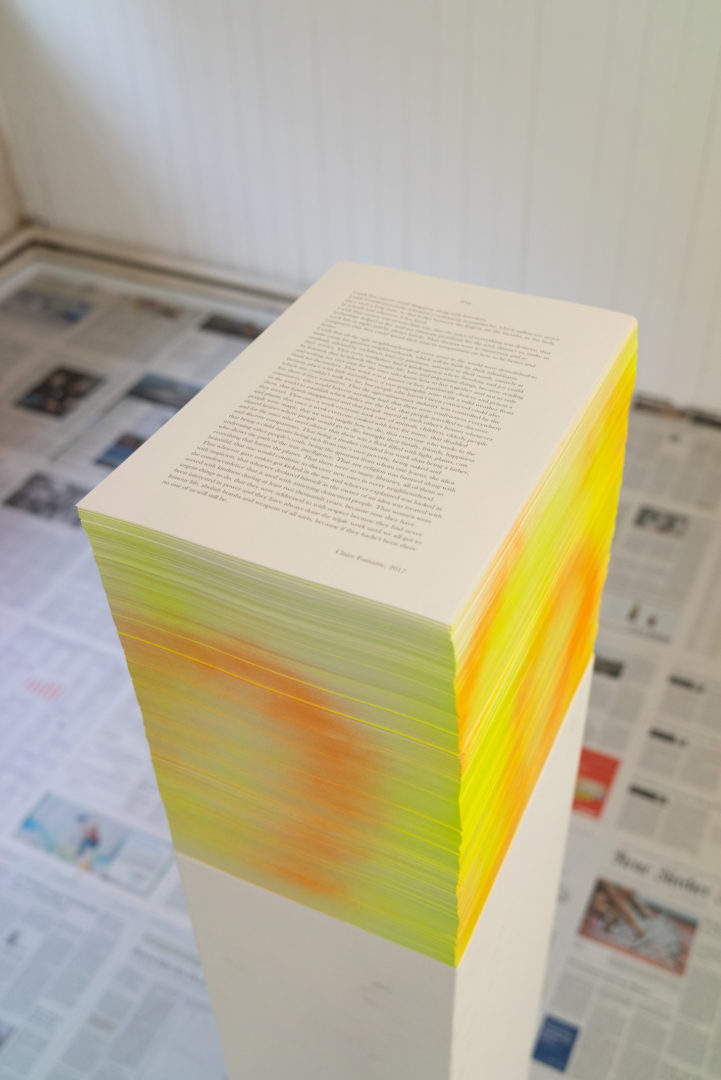

Artists’writings are certainly not rare but those by ready-made artist Claire Fontaine are particularly intriguing as they are spread over about fifteen years and they run aside her artistic practice at times going beyond it and extending the boundaries of its political ambition, while being somehow an essential part of her visual work. This anthology titled Human Strike and the Art of Creating Freedom, which we can certainly qualify as programmatic, was published last March in French by Diaphanes and last December in English by Semiotext€ 1.This enigmatic title that, all in all, resonates with the concept of general strike partially takes up concepts present in many of the texts, such as Ready-made Artists and Human Strike, a Few Clarifications, or Human Strike has Already Begun2. If Claire Fontaine defines herself as the umpteenth ready-made artist in a text offered to visitors in her exhibition at Reena Spaulings Fine Art in New York, she is formulating her programmatic project whose starting point would be to use political powerlessness as subject and means of her work3. This publication is therefore an opportunity for us to talk to the artist and to highlight her importance, by reviewing her artistic practice.

Philippe Szechter : My first encounter with your work took place at the Zoo Galerie in Nantes on the occasion of your exhibition Couvrir les feux, (Covering the Fires) in 20064. One work had struck me at the time as it had to be, if I may say so, “sought for” because it could go completely unnoticed in the exhibition space. The phrase “I HAVE NO WORDS TO TELL YOU HOW MUCH I HATE THE POLICE” was written on a beam on the ceiling above the heads of the visitors by candle flame. This graphic practice was in fact borrowed from the forms of vandalism found in public but enclosed spaces (toilets, elevators, stairwells). Also this game of moving a “vulgar” practice into a space dedicated to the arts seems to me to represent your work rather well, because it often functions as an oxymoron. But before I bounce back on my interpretation, I wanted to know for the umpteenth ready-made artist how do you view the exhibition space, is it a heterotopic space that should be abolished ?

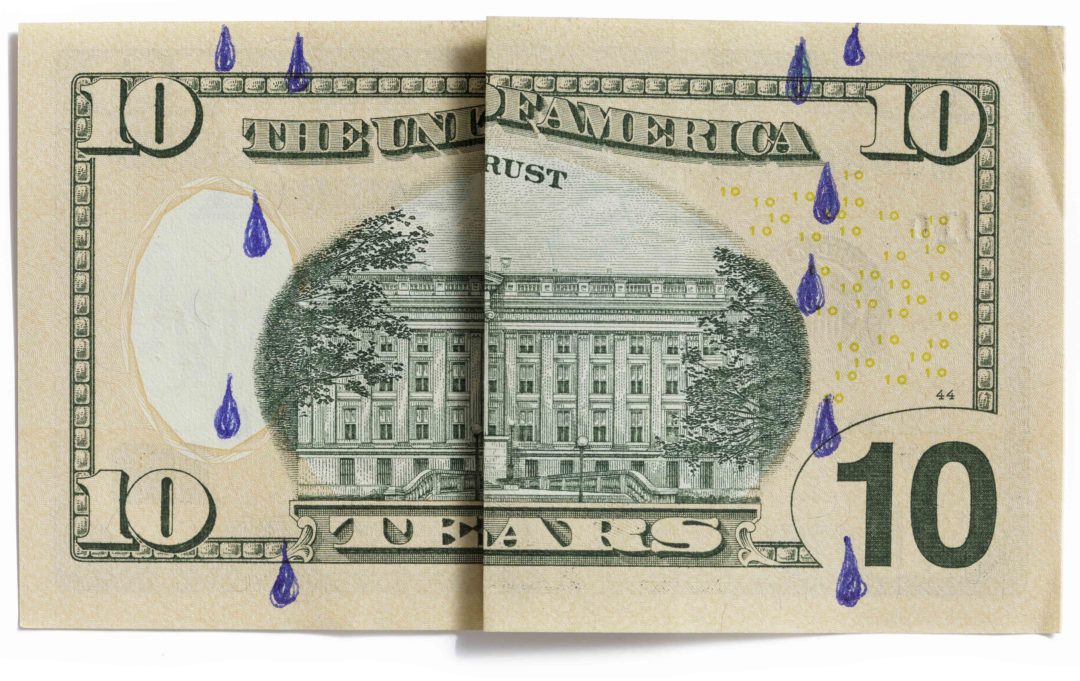

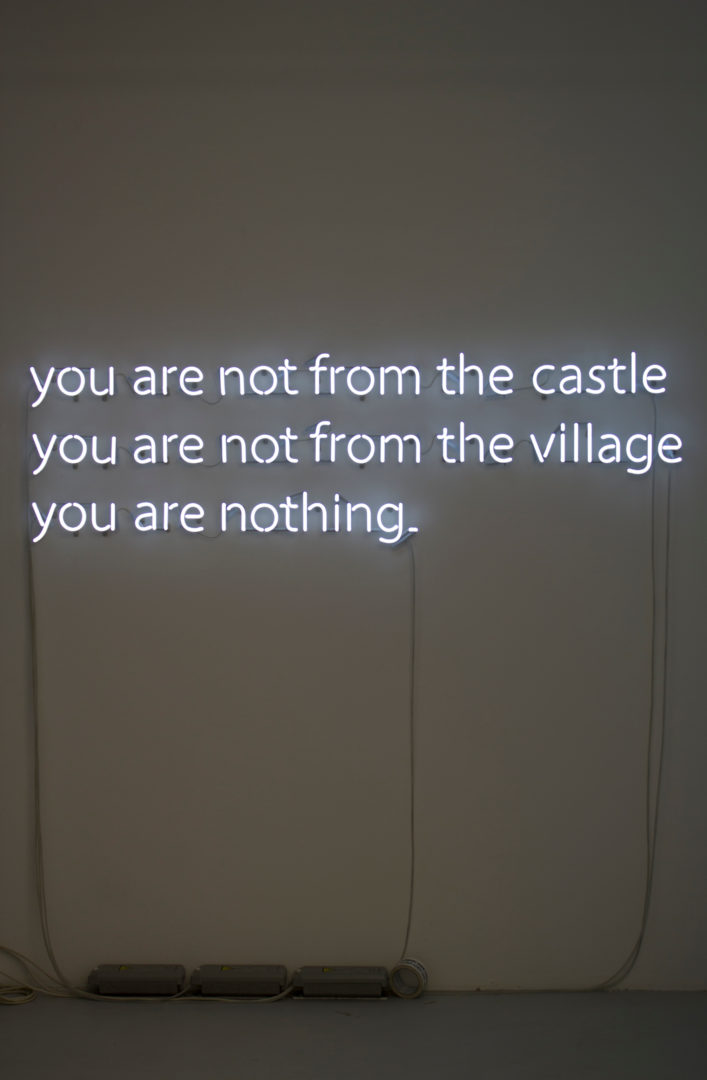

Claire Fontaine : The exhibition space is a place of contemplation. One wonders, as Nick Mirzoeff does, whether it would still be needed in this form in a society free from capitalism. Mirzoeff speaks of a museum which would not erase the use value of the objects presented – in the case of anthropological museums – and which would not have walls. Museums, as institutional critique has pointed out, are places of accumulation and attribution of value, of legitimization of the powers in place. It is the minimum to appropriate them, as artists, and to invest them with forms and contents that the visitor does not expect to encounter. There are no low and high forms of visual expression, as there are no lives that matter more than others, what matters is the use one makes of the forms and of one’s life. Couvrir les feux was an exhibition very strongly centered around the state of emergency and there was also a form of mourning for militant practices. The artwork burnt on the ceiling is a quote from Godard’s Made in USA, but there were also fires devouring their own image in a video projection, outdoor lamps mounted upside down that flashed in sequences, mural tags turned into neons. The idea was to transform Zoo Gallery into a dimly lit night, troubled by riots and pent-up conflicts, to look at all this closely and transform it into an object of reflection, free it from its mediatic image and do it at least visual justice.

To bounce back from your answer, I can’t resist asking you a question – which resonates with the text Invitation5 accompanying your installation which consisted in opening to the public a space, that you had squatted next to your apartment, between 5 p.m. and midnight during three days, this text quotes Michel Foucault’s “Des espaces autres” – that we read differently in respect to the current period where individuals have been put in a situation of voluntary confinement. How did you go through this time ? A period not unlike that of 2007 when in Footnotes on the State of Exception6 you invite us to find lines of flight to escape our “whatever singularities”.

The confinement due to the covid19 control measures has not been voluntary, all transgressions have been punished very severely, it has been the result of an unprecedented operation of mass control. It may be that our relationship to domestic space, which has become a prison, has been radically transformed by this, but what has changed most profoundly is certainly the relationship with the public space, because of our impossibility to meet there, to appropriate it. The whole of society revealed at that time its carceral character : the continuity between the bodies, made explicit by the contagion, also highlighted the continuity between the spaces. Inmates in covid19-infested prisons have infected workers and wardens who returned to their families on public transports, whose children went to school with all the others… Contagion proves that segregation is a mistake of logic before being a political error : we live together, we share a common biological fabric, even the air we breathe goes in and out of each other’s lungs, it can make us sick or allow our survival, we can breathe it through a mask, but this does not change : it is common. The Black Lives Matter slogan “I can’t breathe” has so many meanings and it evokes the sense of social, physiological and psychological oppression that comes from capitalism’s relentless denial of the vital necessity of human community. In the installation you speak of, which we opened to the public almost two decades ago, you couldn’t get inside the space, you could only see it through the bars of an open window ; the interior was a poorly lit ground floor room with peeling paint, a bare space with a toilet which neither curtains nor partitions separated from the rest, it was a kind of cell that we had found when we had occupied the place that used to be a former sweat shop. We had installed a small neon sign that was the size of those of the brands of beer that can be seen in the windows of cafes, the word Lager was written in a fluid and continuous way, but the glass tube had been painted in opaque black and only the electrodes could be seen glowing with their bluish light. Lager is indeed a kind of beer, but it also means “camp” in German, the installation insisted precisely on the continuity between spaces and beings, as did the mural newspaper that was pasted in the neighbourhood and reproduced in our anthology under the title Foreigners Everywhere. In hindsight this period is not that different from ours, the contradictions at work are the same, but today they are exacerbated. During the confinement we have lived as we used to do before, in self-sufficiency, in war, suffering of course the lack of sociability, children’s school and freedom.

In Towards a political imageless education, a rather long text from 20077, you quote Jacques Rancière who affirms that “before being the act of the teacher, the explanation is the myth of the pedagogy, the parable of a world divided into learned minds and ignorant minds”. Do you believe – but is this the right adjective to use – in an educational and emancipatory function of art ? Art as a form of scandalous rupture ?

Of course, art has no educational purpose, it is a wonderful tool for unlearning what we know and looking at the world with new eyes. Moreover, Rancière uses precisely the paradigm of the artist as living proof of the transformative power of the mirror neurons and of the human capacity to make animate and inanimate beings resonate: “Each one of us is an artist,” Rancière writes citing The Ignorant Schoolmaster, “to the extent that he carries out a double process ; he is not content to be a mere journeyman but wants to make all work a means of expression, and he is not content to feel something but tries to impart it to others. The artist […] therefore designs the model of a reasonable society where the very thing that is outside of reason – matter, linguistic signs – is traversed by reasonable will: that of telling the story and making others feel the ways in which we are similar to them.”8

Another text written in 2011 particularly interested me, in 1977: The Year that is Never Commemorated, a text that looks back on the years of lead in Italy. The conclusion, which is a quote from Bifo9, also seems to me to apply to the period we live in today when biopower imposes its security laws. What roles can artists play in these regressive times? Can works of art save us ?

In the conclusion of this text the quote from Bifo describes a crossing of the desert, a journey through inhumanity. In the eighties the historical conjuncture of repression of political movements was such that then began an effective campaign of disinformation (whose effects we are still inheriting) according to which capitalism would have brought not only material well-being but also was a form of progress with civilizing effects. Today we are undoubtedly at the end of this journey, in a totally different situation, because we clearly see how the operating mechanisms linked to a deregulated system, having only economic profit as a touchstone, cannot take into account the humanitarian and environmental impact and put the mere pursuit of life on earth in danger. It is only ourselves who can save ourselves. Art is not there to help people, it has no educational ambition, on the contrary it is made up of risky explorations in territories bordering on madness. If art can give us back the taste for freedom or inspire us in one way or another to act and create outside marked paths, in this case yes, it can give us hope while our freedom suffer from restrictions. It is superfluous to talk about how music, colors, thoughts affect us, each aesthetic experience is transformative, on the other hand we must be ready to open the channels that these sensations use in order to penetrate us. Whether we are in the museum, plunged into a book, at a concert, art is not recreational, it is not a form of nurishment, it is a substance that will react with the chemistry of who we are. This explains the prudence of the institutional programming of museums…

In your writings we meet many philosophers (Agamben, Benjamin, Deleuze and Guattari, Foucault, Lyotard, Rancière) who support your reflections, but also art historians (Arasse, Ginzburg, Warburg). You even sometimes criticize them. Also we would like you to explain to us how these philosophical reflections relate to your artistic practice. Are your aesthetic choices, which are akin to the ready- made – even if Duchamp affirms that “The ready-made is an aesthetic object which has no aesthetic”10 – only semantic ? Isn’t the ready-made artist doomed to wait for critical thinking to develop for the work to take on meaning ? Finally, we know that a work of art that claims to be political loses its subversive power over time – I am thinking, among other things, of this work by Manet, L’Evasion de Rochefort that no one could take for anything but a marine view if the title wasn’t there to suggest something more than a landscape painting. So shouldn’t Claire Fontaine burn her produced works as soon as the context changes and no longer repeat them ?

The work of art enjoys a certain amount of autonomy from its times, it is often in an eccentric position, not necessarily contemporary of its present, sometimes turned towards the past, sometimes prophetic and incomprehensible to its own contemporaries. What you describe in the last part of your question seems to me to apply to art as a monument: the celebration of the powerful – not of the oppressed people and the repressed feelings but of the heroes, of those who have a place in the official historical narrative – fortunately tends to age badly. The exciting debates over the elimination of the Monuments of Confederate Soldiers in the United States prove that these artifacts must go and that their expressive quality is too insulting to be considered an acceptable testimony to the distant past. The question of the interpretation of the contents of referential, historical or quite simply conceptual origin in a work is an entirely different one. The story of the forms and the forces that art captures through the ages is fascinating to everyone, as the research of Warburg and of so many others proves, there are survivals, ghosts, it is very exciting to recognize them if we can. Otherwise, the work of art can still benefit from an intuitive, immediate dialogue with its viewer. Its form, its composition, its energy touch those who meet it in ways that the artist cannot and should not control. The ready-made, by Duchamp’s own admission, and a number of art historians’, possesses an aura, it is of course not a purely conceptual operation, the infrathin exists, it’s up to us to recognize and grasp it. Our works are not leaflets, and even leaflets and posters, as they age, as the surrealists have explained, acquire powers similar to the ones of the works of art. Just look at the fate of the May ’68 posters.

Our art practice and our theoretical practice coexist, they do not complement each other, one neither illustrates nor explains the other, we think by concepts as we think by forms, everyone has a physiological life and an intellectual life, a sexual life and a social life, there is nothing surprising in exploring different registers of expression, it is the peculiarity of art, to exist by ignoring these conventions. There are so many artists who write, so many philosophers who paint or play music. Even advances in contemporary medicine tell us that the intestine is as important as the brain, that our emotional and physiological life heavily influences our intellectual capacities, and that our friendships affect our cognitive abilities. Everyone should have the freedom to be able to do everything while ignoring the hierarchies imposed on us. They perpetuate a dying society that thrives on the destruction of non-renewable resources and contempt for the living.

Another corpus appears in your texts around a certain number of artists, Marcel Duchamp, Jean-Luc Godard, Marcel Broodthaers, or even Philippe Thomas11. It reveals your interest in exhibition devices but it also highlights the relationship that artists have with curators12.

The artist is an ambiguous professional figure because his skills and excellence are judged on the basis of obscure criteria. The three artists you mention have all positioned themselves in an atypical way towards art history and the place they sought to occupy in it. Duchamp was fully aware that one could have created the most wonderful work of art imaginable while living deep in the jungle and that no one would have known of it, that therefore the narration of art history is, like any narration, extremely partial, tied to power relations (all the mentioned artists are white males). Broodthaers went so far as to create his own museum of the department of eagles, to make fun of the conventions which preside over the the attribution of value to the art object and he often made rather funny considerations about the figure of the artist and his opportunism, his complicity with a system that keeps him alive while at the same time degrading him. Philippe Thomas sold his copyright, he literally dissolved himself into his collectors to transform them into messengers of his works that have become theirs. As for Godard, he is an incredible border-line figure, who systematically pushes all certainty to a loss, I believe that his exhibition at the Pompidou in 2006 is one of the best shows of the last decades. The author-function is in crisis but the desire to be an author remains strong, it is interesting to desire something else and we can do it by opening ourselves to other narratives than the official ones. Recognition does not only come through the power that we have over others (less powerful than us), it is much more intense when it is the result of horizontal elective affinities. Curators are important figures because they can create and undo constellations ; catalogs and exhibitions are nothing else than activations of movements of thought which ask to become movements in real life, movements of passions, politics, aesthetics.In our book we are constantly constructing constellations, because the links between authors and ideas create a use value for references and we are very interested in the transformative power of concepts and images, affects and experiences. This is why feminism is for us both an epistemology and a form of life, an ethical tool and a way of relating to one’s body and one’s desires.

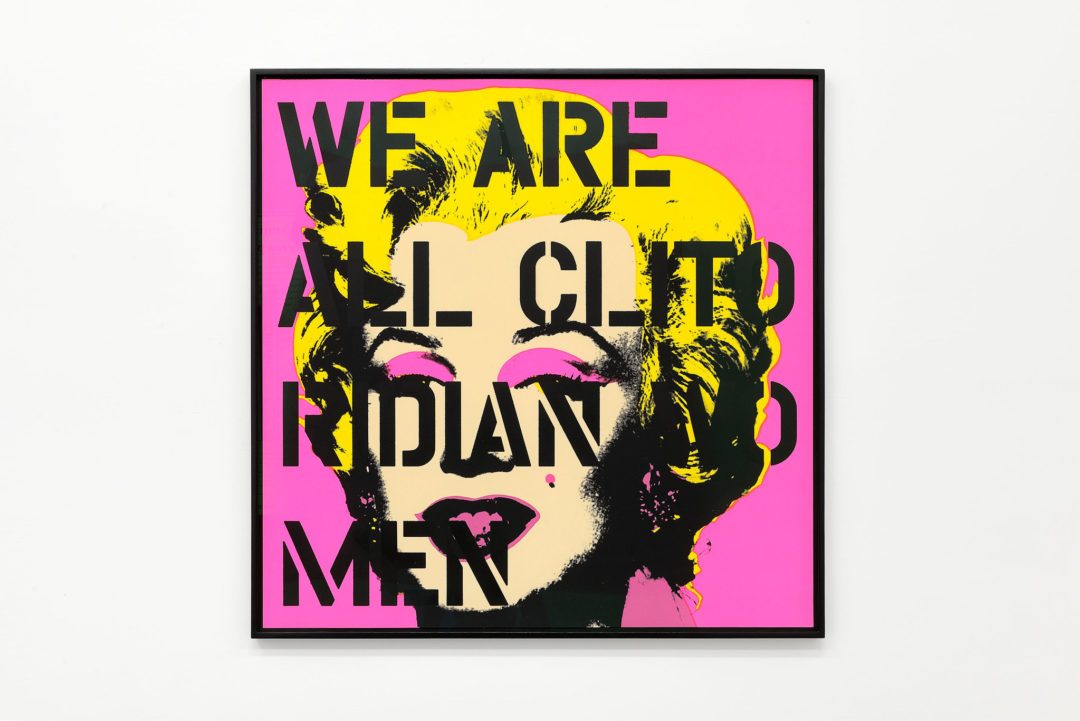

The question of women’s struggle for their emancipation is also very present in your texts. Which leads me to wonder if Claire Fontaine’s works are feminist ?

A. Absolutely yes. Claire Fontaine is an artist composed of a man and a woman but she is a woman artist. Feminism is a way of questioning the value normally attributed to things and people. Patriarchy thrives by degrading and devaluing the beings that it needs the most and that it exploits the most intensely, we must unmask this state of affairs which makes reproduction less important than production and the labor of care either an underpaid or an unpaid activity. The fate of devalued beings is of little concern to the general population, value is a form of occupation of space, economic but also mental and political. Lack of value corresponds to a lack of existence, this is how we understand the slogan black lives matter. There would be a lot to say about the term “emancipation”, we prefer the idea of the practice of freedom : women’s freedom is never thought of in the absolute sense, it is the freedom to choose not to get pregnant against their own will, not to be raped, not to be killed by a furious man, to be able to take part in the male world of work while experiencing motherhood in a schizophrenic way and their difference as shame. It is the freedom to suffer less or otherwise. This is why women’s pleasure is a wasteland yet to be explored, not only sexual pleasure, of which the generalized ignorance is grotesque, but also cultural and existential pleasure. Even products created for women are designed so that men can enjoy them better as objects, not so that they can enjoy life as sujects. This is why human relationships are desperate : men cannot bear to desire a strong, free, happy being. They are used to do so little to make themselves loved that they would live in fear of being abandoned. Let’s think about it.

Finally, for Claire Fontaine, how does the magic materialism that you theorized in your last text13 of 2019 apply, it’s a text that seems to me to be somewhat at odds with your previous political texts? What about Claire Fontaine’s artistic output today ? What artistic projects are you pursuing in this period of global epidemic, anti-racist struggles like Black Lives Matter, feminist movements like #MeToo and struggles against global warming ?

We have named ‘magic materialism’ the political sensibility that allows us to transvalue many skills and aptitudes presently relegated to a vague immaterial space, whose quality isn’t appreciated or remunerated adequately. Magic materialism, unlike historical materialism, is a tool to unmask real abstraction: the situation in which the commodity, and the relationships that revolve around it, are perceived as “materially real”, where we think that one hour of our work is worth 15 euros. Magic materialism is not irrational, the term “magic” applies to things that science can’t explain or can’t see but are there nevertheless. Remote work and enforced seclusion have relatively little effect on artists, who still live, no matter what, a very lonely life and travel only for work. Having received beautiful invitations during these strange times we have honored them: Hito Steyerl has asked us to contribute to Letters Against Separation14 last March, Texte zur Kunst has invited us shortly after to reflect on how the pandemic has transformed our vision of the world and the relationships between people, we wrote a text called The virus is our idea of ourselves15. Purple, who recently ran a special issue on love, asked us for a piece in which we focused on the paradoxes of heterosexual love ; in The 25th hour, we argue that the twenty- fifth hour would be the moment in which the love of women for men would become possible, after all the daily efforts that women must make and their systematic exploitation. We have also developed a local art project in a working- class neighborhood of Lecce with Studio Concreto16, which first took a virtual form with a video on the hallucinatory mental state of the confinement17 and then, when travel became easier, came back to its original form of street assembly. We have, among other things, a project that is close to our hearts with the Museo del Novecento in Florence, which will run over several months and which, since the museum is closed because of Covid, takes place on the pages of newspapers and in the public space – we have already intervened on the occasion of the day against violence on women with an online conversation as part of the museum’s program and we are going to install a work on the facade on the occasion of remembrance day in January – we will inaugurate this first part of the work on December 12th18. In general I would say that the virus has exacerbated almost all the contradictions of capitalism, the artistic practice of Claire Fontaine is always in evolution but to those and those who define it as radical we would like to recommend, in case their daily life does not seem to them much more brutal than our work, to read the newspapers and watch the news: reality is a thousand times more radical and disturbing than any of our works.

- Claire Fontaine, La Grève humaine et l’art de créer la liberté, 2020, Diaphanes éditions Zurich-Paris-Berlin

- Ibid., Artistes ready-made et grève humaine. Quelques précisions, texte de novembre 2005, pp. 24-44 / La grève humaine a déjà commencé, 2009, pp. 111-115 / La grève humaine dans le champ de l’économie, 2011, pp. 130-140 / Note méthodologique, 2012, pp. 200-203

- Claire Fontaine, La Grève humaine et l’art de créer la liberté, 2020, pp. 14-18 et p. 333

- Communiqué de presse, Exposition Claire Fontaine, Couvrir les feux, Zoo Galerie, http://www.zoogalerie.fr/wp-content/uploads/2009/04/cf_communique_de_presse.pdf

- Claire Fontaine, La Grève humaine et l’art de créer la liberté, 2020, pp. 7-8

- Ibid., pp. 49-56

- Ibid., pp. 72-90

- Jacques Rancière, The Ignorant Schoolmaster, Verso, 2011, pp. 70-71

- Claire Fontaine, La Grève humaine et l’art de créer la liberté, 2020, p. 167

- Ibid., pp. 220-231 (Ready-made, généalogie d’un concept, 2014)

- Ibid., pp. 173-193 (ACM, 2012)

- Ibid., pp. 194-199 (Curateurs invisibles, 2012)

- Ibid., pp. 323-332 (Vers une théorie du matérialisme magique, 2019)

- https://conversations.e-flux.com/t/letters-against-separation-claire-fontaine-in-italy/9701

- https://www.textezurkunst.de/articles/claire-fontaine-idea-ourselves/

- https://studioconcreto.net/en/claire-fontaine-la-fine-del-mondo/

- https://studioconcreto.net/en/claire-fontaine-i-we-yes/

- The artwork “Siamo con voi nella notte” in neon is installed from December 12th to March 11th, 2021. https://www.clairefontaine.ws/

Image on top : Installation view : Claire Fontaine, ‘I say I’, Dior Autumn/Winter Catwalk 2020/21, Jardin des Tuileries, Paris (25.02.2020) Courtesy of the artist and Dior. Photo credit : Daniel Salemi

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Jacques Lizène’s laugh echoes on in my mind.,

Related articles

Céline Poulin

by Clémence Agnez

Calla Henkel & Max Pitegoff

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Dena Yago

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad