Hanne Lippard

KW, Berlin, 20.01—9.04.2017

“I’m certainly not a poet, I’m a meagre writer, which is probably why I talk about oral communication. I’m not a poet and I see oral communication like a sculpture”. This statement comes from an artist who has made discussion his favourite medium, focussing on creating situations which cannot be tested by proxy. In the mid-1960s, the South African Ian Wilson (because no, Tino Seghal does not have a monopoly on presence) decided once and for all to abandon the brushes and stretchers which had been part and parcel of his early years as an artist. Like the New York Conceptual artists, whom he was close to, hanging out with the Joseph Kosuth/Robert Barry/Lawrence Weiner gang, de-materialization would gradually get the better of any kind of attachment to form in his work. For him, even writing was still too dependent on a material wrapper, freezing it in a dissymetrical time-frame somewhere between the creation of a meaning and the way it would be well-received after the fact. His art, he declared at that time, would be “information and communication”, it would be dialogue and joint creation. In 1968, his work procedure was all set up. Evidence of this was Time (spoken), still to this day one of his best-known works. At openings for his shows, the œuvre was being constructed little by little as he moved among visitors, triggering their socialite twittering, systematically answering with the word “time”, when he was asked what the subject of the show was, or what research he was involved in . No physical trace of these exchanges remains, recording being formally banned, just mnemonic leftovers.

From left to right: Hanne Lippard, Flesh, 2016. Courtesy Hanne Lippard ; LambdaLambdaLambda, Prishtina. Ian Wilson, Time (spoken), 1982. Installation view KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, 2017. Photo: Frank Sperling.

Ian Wilson, we might say, is Tino Sehgal without the media hype. But what differentiates the scope of their works does not have to do so much with their intrinsic intentions and approaches, which are more or less identical, as with the cultural setting in which they took place, and which determines our understanding of them. Born respectively in 1940 and 1976, a generation divides them. In fact, through his “social sculptures”, Ian Wilson achieved an inclusive approach: from then on, the work could be made by anyone and everyone and, as a result, the very condition of its existence depended on that plurality. The ban on documenting the process thus seems simply to be a way of not carrying on the position of author, by transferring it to the person with the archive, be it an artist or an institution. When, on the other hand, Tino Sehgal started to produce his first situations in the early 2000s, he was seen as introducing an act of critical withdrawal, constructing his œuvre in a de facto state that has since become established, the disease of institutional ‘archiveness’ (‘archival impulse’, is how Hal Foster put it in a more sober way) and above all of the premises of frenzied documentation by a public which would, as we well know, change into homo instagramus.

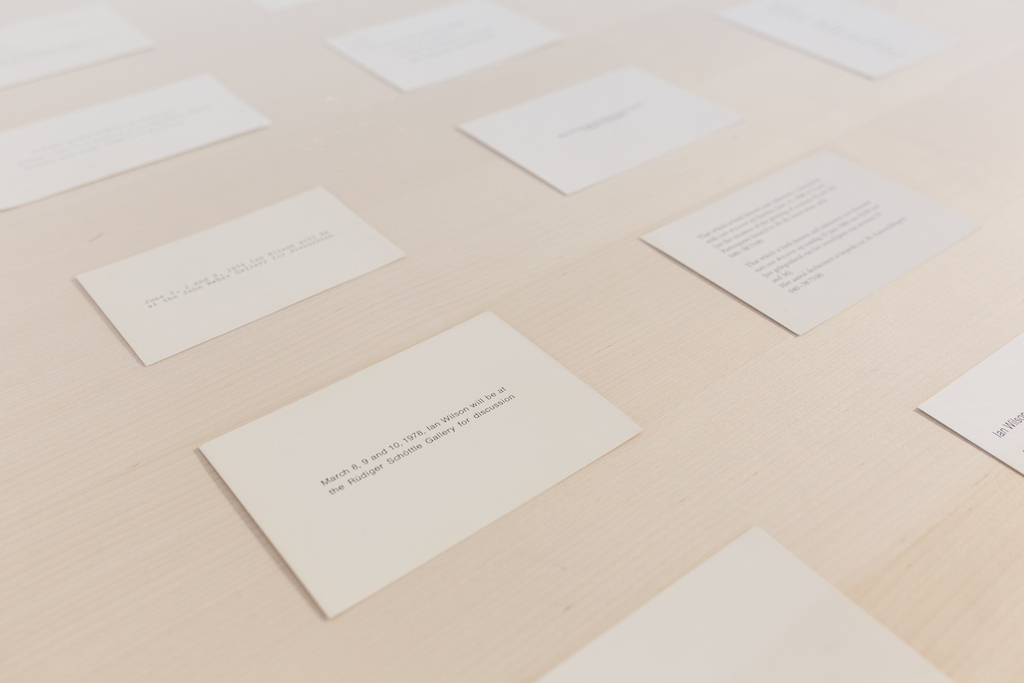

Ian Wilson, A discussion in context of an exhibition, March 8, 9 and 10, 1978, Galerie Rüdiger Schöttle, Munich. KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, 2017. Photo: Frank Sperling.

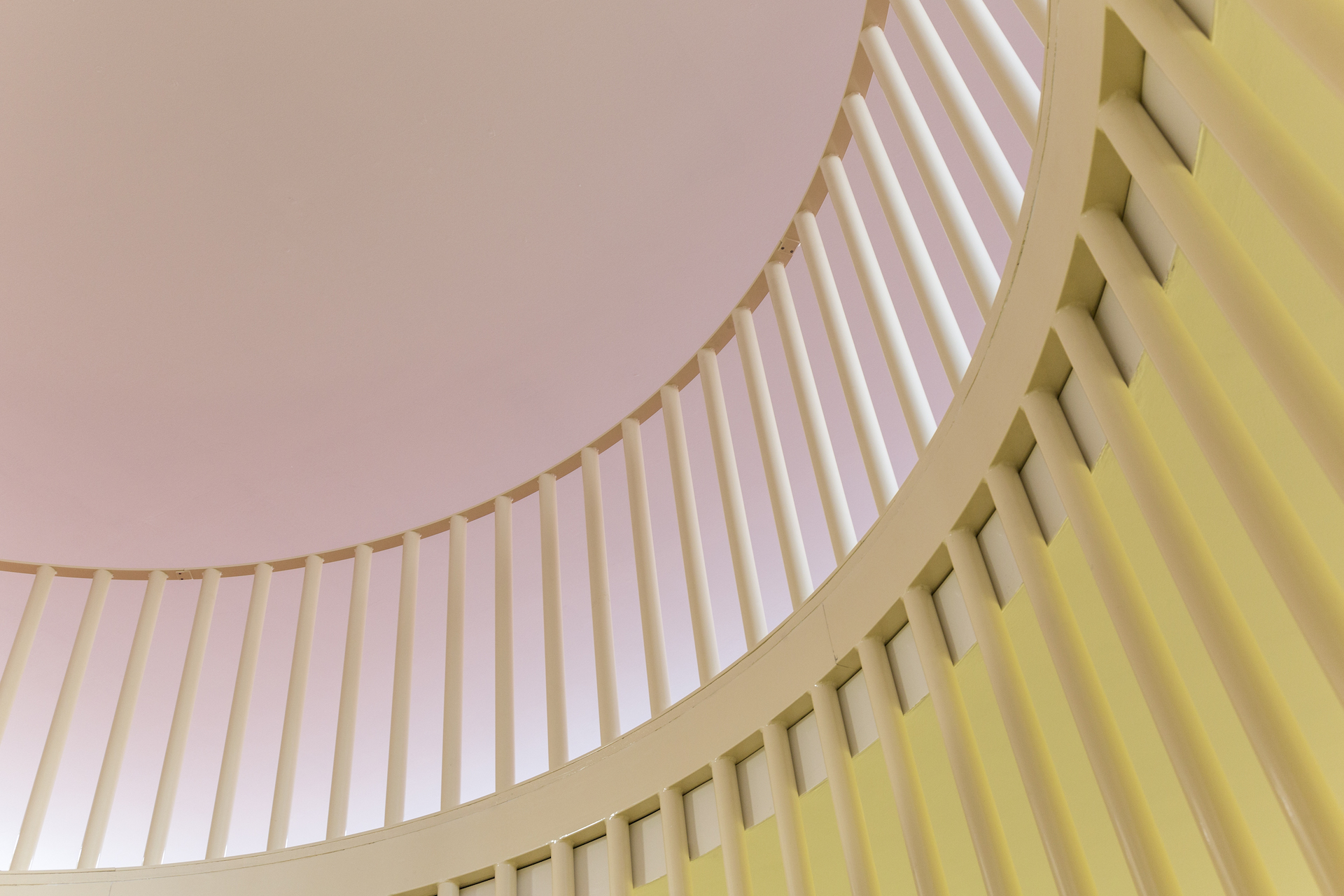

The voice, which is the most immediate medium given to the human being to do something with, is thus far from being devoid of history. We are reminded of this fact by the KW Berlin—and its new director Krist Gruijthuijsens—by getting a dialogue going between two artists each working from their media context on orality: Ian Wilson, and Hanne Lippard. For her first exhibition in an institution, the young Norwegian artist, born in 1984, is presenting Flesh, an immersive listening environment which wavers between the adjectives bureaucratic and uterine. Beneath a ceiling lowered to a mere 50 inches, with access by way of a yellowish beige spiral staircase, a cramped space with flesh-pink wallpaper houses two speakers. Wafting intermittently towards us comes the monotonous, hypnagogic and synthetic phrasing typical of the artist’s performances, declaiming a hyper-real poetry where just a handful of discordant elements—a whiff of a Nordic accent in internationalized airport English, a letter over-emphasized on purpose—tell us that we are not attending a Siri recital.

A graphic artist by training, Hanne Lippard has also decided to work exclusively with the voice–her own voice and no other–as a medium. With her, however, faced with the inevitability of the rogue recording, the matter of the voice is conceived, on the contrary, as a way of sidestepping the diktats of the new economy of presence, that “tyranny of being there”, aptly pinpointed by Hito Steyerl, identifying the authentic experience as the most sellable value of present-day contemporary art.1 For Lippard,2 orality is separate from presence and, conversely, through individual and on-the-move listening in earphones, makes it possible to re-introduce accessibility to the source of Ian Wilson’s experiments, but without toppling into the fetishization of joint presence which, as a last resort, is precisely tantamount to restoring to the institution the power of validation, from which it was a matter of escaping by doing away with the material content of the idea

You are one of those rare artists working with only one medium. How did you decide to focus on spoken language?

Hanne Lippard, Flesh, 2016. KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin. Courtesy Hanne Lippard ; LambdaLambdaLambda, Prishtina. Photo: Frank Sperling.

I’ve always been interested in writing. As a child, I always thought I would become an author or a journalist. Then I discovered there was also this interest in the visual aspect, and that I could combine both in graphic design so that’s what I went on to study. I studied at Gerrit Rietveld Academie in the Netherlands, which has a very conceptual approach about how you get the message accross. But what was most important for me, and also shaped my practice with voice today, is the physical aspect that exists in manipulating text, in an almost primitive way where you step back from the usual approach of written language. I got interested in the rhythmic aspect of the text, that I had previously interpretated as typography, but I was missing a more personal and physical aspect in the work. That’s where my first attempts with voice stem from: a need to step away from a predefined form and leave it to improvisation during the performance.

If speach becomes a shapeable matter, be it through typography or orality, thus transformed, to borrow Ferninand de Saussure’s terminology in “accoustic image”, what role does narration play in your pieces?

Hanne Lippard, Flesh, 2016. KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin. Courtesy Hanne Lippard ; LambdaLambdaLambda, Prishtina. Photo: Frank Sperling.

My writing process is almost always starting from a found element of language. It can be a sentence, an advertising slogan or a bit of writing that I see in my daily life. I’m always interested in standardized language and repetitions, where you have a series that is starting to build around variations of the same topic. One of the first real works I made is this video called Beige. For this piece, I started from general leads about this unspecific colour that permeates the whole society and is found in all globalized spaces replicated all over the world. This was seven years ago, I was twenty-five and I realized I was suddenly drawn to wearing this non-colour, this pleasing colour of the adult world by choosing chic, neutral and monotone tones for my clothing. Then, by chance I found an article at the same time saying that scientists had identified the unifying colour of the universe, and that it was this rather boring and deceptive bland beige called “Cosmic Latte”. This piece actually plays on most of the elements that you find in my work: a way of building echoes between the ideas and words, as well as the neutral tone I express them in. Since I am always the person who reads my pieces and because I use the first person narrative, almost everyone thinks there is a story. It’s also because of the female voice that you automatically feel drawn to and identify with, which is why you have so many programmes for personnal assistant apps or chatbots that are being made to resemble a female voice. Nowadays, I also take a lot of interest in voice command programmes like Siri, the voice being used by iPhones, or all the tutorials that you find on Youtube, which have developed their own distinctive way of speaking.

You always read your texts yourself. Have you already thought of having someone else do it?

At the beginning, I actually thought about having someone else read them. However, I felt it would be like leaving the sculpting or shaping process to someone else, which some artists do of course, but for me, the reading is as much an essential part of the work as the writing beforehand. Also, when I’m writing, there is this voice that is underlying in most pieces, and that also comes from the process of collecting and sampling existing language elements from everyday life and the Internet. Even when I show them in another country, my pieces are always in English. I grew up bilingual, speaking both English and Norwegian at home, and I now live in Berlin. But precisely because I have grown used to shifting between the two, I have developed a specific English that is not very advanced or academic, but more like a commercial language or the one you find in self-help manuals. Which I think everyone can understand and get something out of.

With the development of previously mentioned voice command programs, an evolution that French journalist Nicolas Santolaria recounts in his recent book Dis Siri, do you think that we could be witnessing a come-back of orality inside the “Gutenberg galaxy” that tried to do away with it?

Someone recently told me that most teenagers nowadays record their messages instead of writing them, because they’re going crazy with all those text messaging-apps. However, I don’t think we can really go back to a civilisation of orality. There is a media theorist, Walter J.Ong, who wrote a famous book called Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word, where he explains very clearly that unless a nuclear war destroys all life on earth, we’ll never go back to a primitive orality. However, it could very well be that we are going towards a secondary orality, one that is conscious of its written heritage. And that’s also where my work comes in, since it’s aware of the printed text – and even more so because I studied graphic design. I’m interested in the proccess of translating it back again, from written language to speech, and the part in orality where accidents and imperfections can interfere and break up a clear communication. There is one of my pieces called “The Ssecret to SsucceSs iSs in the Ss-eSs” that is about those interferences: it’s not really my text, since I only slightly modified a text from an American self-help book for start-up entrepreneurs, explaining what the steps to success are. Rut when I read it, I slightly overpronounce the “s”es, which in the long run creates a kind of discomfort in the audience even if the text itself is still very positive and encouraging.

How do you exhibit your performances in an institutional setting, especially on a large scale, like in the show that you are currently doing at KW in Berlin?

I started with performance in a very natural way – and also because for a young artist, it’s a cheap and easily transportable medium! It’s only in the last two or three years that I really started asking myself questions about the creation of the room where I was showing my works. For me, it’s also about how to master the attention, since people today are really distracted in general. Do you want to build something to go against that or do you just accept that as it is? At KW, only twenty people at a time can enter the space that has been built to present the recording. And at the same time, I also chose to leave quite a long moment of silence before one piece ends and the next one starts, so that I wouldn’t force people’s attention but keep it floating like in a natural environment, where you also hear other voices and sounds around you. Of course, at one point, I started asking myself how I was going to document or archive my works. But it quickly became clear to me that even if I worked with a time-based medium, I didn’t want to fetishize presence or be this artist you can only experience in reality. Looking at my pieces on a laptop is one possible way of experiencing them. I think this is the case with most artists of my generation, and one has to take into account that Tino Sehgal’s position of forbidding documentation is also that of someone from an older generation. When I started out, there was always someone already filming with their phone anyway. The reception of my works is very physical, it’s about making a body to body contact through the voice, and it’s walking the fine line between the literary quality of language and the sensory presence of the voice and all the imperfection. But I also think that we don’t really react differently yet to a real voice and a synthetic one, as there will always be this affective identification with the speaker, be it live, with good quality speakers in an institution or at home in front of one’s laptop. In the movie Her by Spike Jones the main character falls in love with the disembodied voice of a computer programme, so I think I can be totally satisfied with people watching my performances on their laptops!

1 Hito Steyerl, “The Terror of Total Dasein” http://dismagazine.com/discussion/78352/the-terror-of-total-dasein-hito-steyerl/ “the contemporary economy of art relies more on presence than on traditional ideas of labour power tied to the production of objects”.

2 … she would have fun sharing her last name with the high priestess of de-materialization, producing a piece titled Luci Lippard https://vimeo.com/149143638

(Image on top: Hanne Lippard, Flesh, 2016. KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin. Courtesy Hanne Lippard ; LambdaLambdaLambda, Prishtina. Photo: Frank Sperling.)

- From the issue: 81

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion, Hoël Duret, CLEARING, Nicolas Bourriaud, Mark Alizart,

Related articles

Céline Poulin

by Andréanne Béguin

Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Interview with Warren Neidich

by Yves Citton