Nathalie Ergino

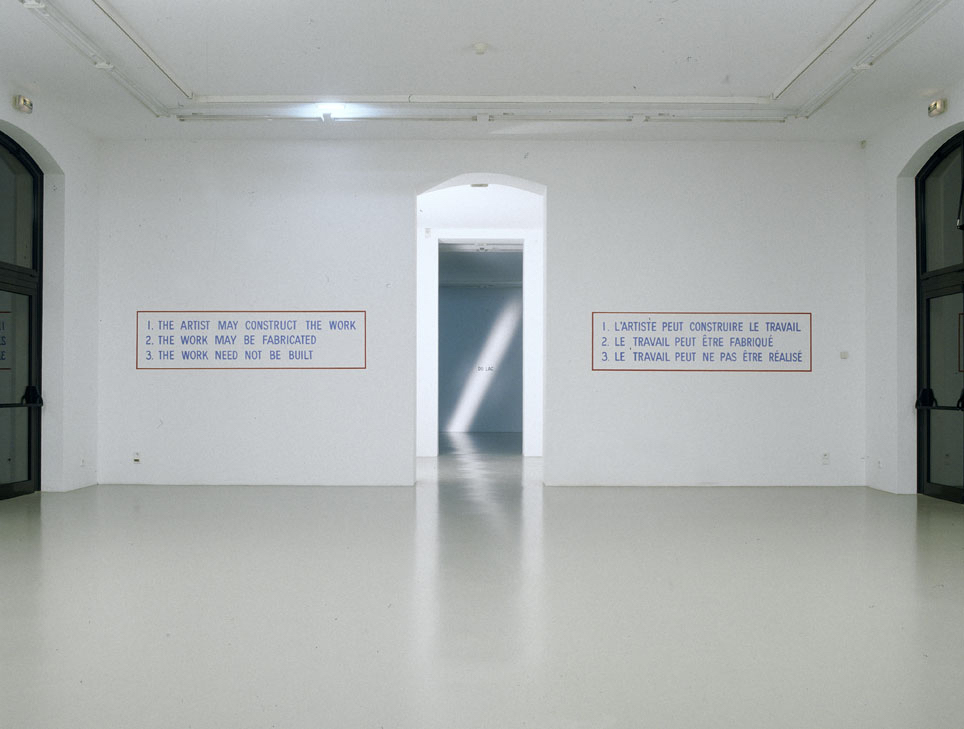

The Institute of Contemporary Art (IAC) in Villeurbanne celebrated its 40th anniversary in 2018. From the creation of the Nouveau Musée [i.e. New Museum] by Jean-Louis Maubant in 1978 (as a reference to the New Museum in New York) to the birth of the IAC following the association’s merger with the Rhône-Alpes Regional Contemporary Art Collection (FRAC) in 1998, the art centre was one of a handful of pioneers in France, alongside the CAPC in Bordeaux and Le Consortium in Dijon.

In no time, it stood out for exhibiting international artists. As a museum with neither walls nor a collection, created on the basis of corporate patronage, it set up shop in 1982 in an old Jules Ferry-type primary school made available by Villeurbanne’s socialist mayor, Charles Hernu. In those days, the art centre, devised as a place for both creation and training, was a documentation centre accessible to researchers, while at the same time developing an important publishing policy. That spirit of research was rekindled by Nathalie Ergino, when she became the IAC’s director in 2006, who made actually experiencing the artwork a special area of study. Since 2009 she has been working on these issues in a more precise way in the Laboratoire espace cerveau [space brain laboratory], a platform which she ushered in together with the artist Ann Veronica Janssens, and which brings together artists and scientific researchers.

Ilan Michel: The IAC’s activities range from producing works to putting together a collection boasting 1,900 pieces, directly associated with the research projects undertaken at the Institute. Would you please describe the historical features of this art centre and the artistic choices that you have made in it? What are the principles which you call the “IAC’s DNA”?

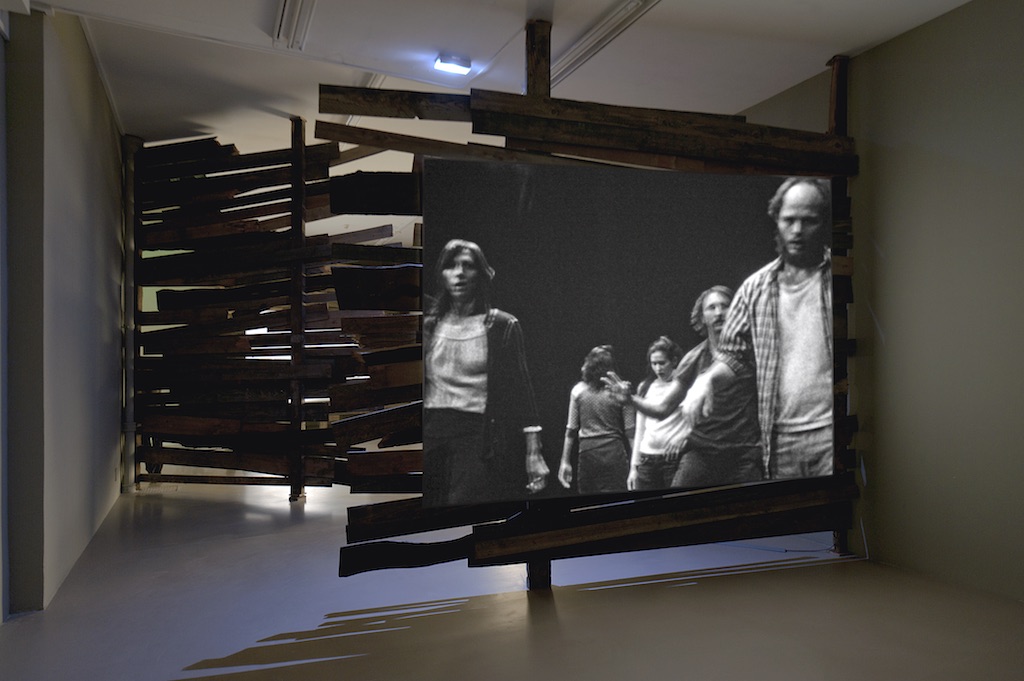

Nathalie Ergino: Given the IAC’s history, I have taken up a stance that is more structural than artistic. Jean-Louis Maubant’s legacy is an intellectual legacy. The word “Institute” is important for me: the fact of taking time, and researching. I’ve tried to reinstate this dimension by relying on an earlier experience. The long-term artists’ residencies which existed at the start of the Nouveau Musée’s history (including in particular Tony Cragg and Daniel Buren) represented, for example, formulae which I would like to re-inject into the future. Since my arrival, the IAC’s DNA has become more assertively creation-and-research, with no distinction between these two themes, in a relation of real synergy. Up until 2016, our artistic identity was associated with perception and space, understood as material. It’s in proceeding by way of these issues of spatialization, loss of landmarks, and altered states of consciousness that we have managed to single out new approaches which go beyond the binary contrasts of body/mind and intuition/rationality, and aim at a research which leads to the merger between man and his environment.

By becoming the “Institute” of contemporary art, the art centre effectively asserts its experimental dimension, underpinned by the idea whereby art is an object of study making it possible to read our world in a new light. What lines of thinking have you introduced and how do they operate?

Jean-Louis Maubant launched the word Institute in 1992, keen to include this notion of in-depth development and also to make the art centre a place for training young artists. This training principle, this Institute of the institute, has really been operating since my arrival with, for example, the “Galeries Nomades” programme, and the exhibition-curating master-class conducted with the ENS in Lyon. Then the space brain laboratory has made it possible to give shape to research since 2009. This research is organized in stations, which is to say public study days, in situ or ex situ, depending on the works chosen. Guests vary with each research theme, and all those registered become potential participants. With the new cycle, there is a desire to broaden this “sharing of imaginations”: everyone receives documentation ahead of time and archives at a later stage, and a Facebook Live is systematically set up. There is also a sort of “Lab School” for young artists, taking the form of three-year cycles, with the idea that contact with researchers may offer them additional tools. These questions lead to our mediation tools, in particular the way of exhibiting our collection in situ since 2014, the “Studied Collection”, the “experiencing the work” visits, and the “body-space” workshop which we are starting this year.

The space brain laboratory has long been questioning the relations between space, time, body and cognitive psychology, based on the experience of perception. Since 2016, a cycle of reflection has begun, questioning what the human being shares with matter. Could you tell us something about your research themes and the links with the contemporary art scene?

The laboratory has in fact started a new research cycle which is exploring the links connecting the human to the cosmos, and trying to get beyond an anthropocentric vision of the world in the Anthropocene age: “Towards a cosmomorphic world”. When I use the word ‘cosmomorphic’, to espouse the notion used by the philosopher Pierre Montebello, in turn borrowed from the anthropologist Maurice Leenhardt, who coined it in the context of animist Melanesian societies, this is a working objective, not a definition. It’s up to us to invent definitions. It’s invariably a matter of developing a broader perception, but by freeing ourselves from the boundaries between body and mind, nature and space, human and non-human. The works which are part of this line of thinking no longer make reference to the subject conceiving them, but become direct captures of the world.

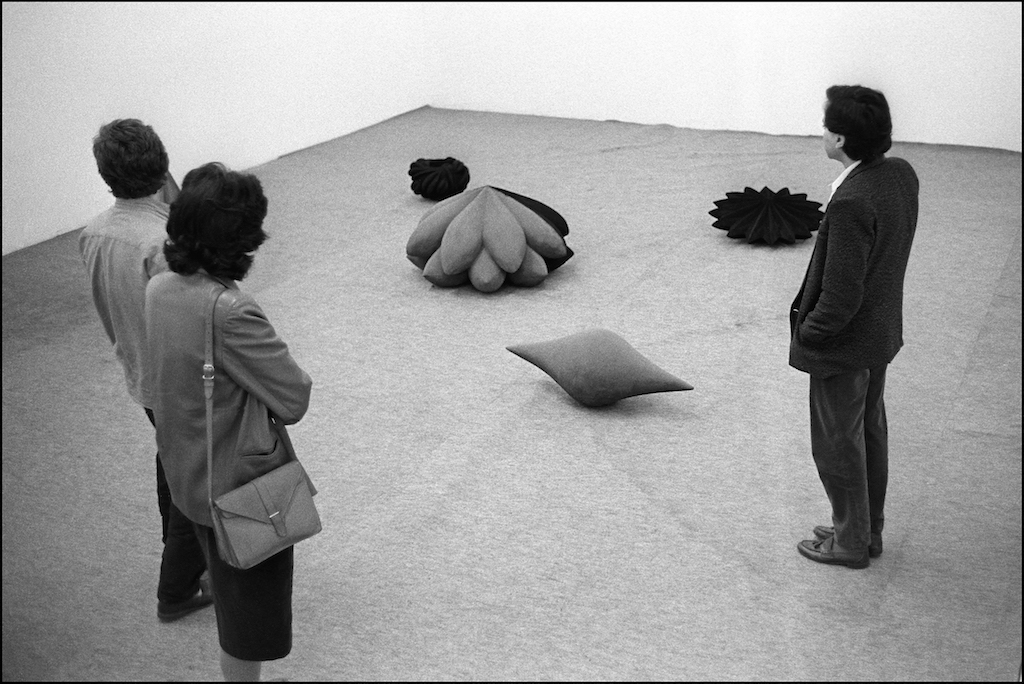

These questions came to the fore with the “Kata Tjuta” exhibition (2015) which explored the physical and metaphysical links between the mineral world and the cosmos, including, for example, the research undertaken by James Turrell, Walter de Maria, Hamish Fulton and the more contemporary Hicham Berrada. This research has been continued with the work of Charwei Tsai and her relation to oriental philosophy, Jef Geys’s work dealing with the borderline between urban and organic using medicinal plants, Katinka Bock’s work, as well as Daniel Steegmann Mangrané’s, whose works offer visitors a chance to be both the object and subject of experience: “If there are no more subjects and objects, there are no more visitors or artworks, but just processes involving relations of mutual transformations”, in his own words. This year, the invitation from the FRAC Ile-de-France to the Château de Rentilly can, in a way, be regarded as an extension of the IAC’s forty years, because this project is enabling us to shed light on our own at once structural and artistic DNA. With “From Immersion to Osmosis, Chaosmosis #2”, we can more clearly explain the synergy between the lab, the exhibitions and the collection, and elucidate the previous programme, very focused on issues of perception and space. As if the immersive process were becoming a tool of osmosis with the cosmos.

If the Institutes spaces are suitable places for carrying out such experiences, how do you connect them with the Villeurbanne area and the wider region? Does your artistic line differ depending on exhibition formats and the host venues?

The ex situ projects are really specific in their challenges and, even if I’m trying to turn them into an extension of our research method, they respond more to a deliberately educational objective which, with regard to the highlights of the collection, proceeds by way of a trans-historical approach undertaken by an artist. This year, Katinka Bock, who has just produced a personal in situ project, will propose a show at two venues in Bourg-en-Bresse, H2M and the Royal Monastery of Brou. In 2017, Evariste Richer held an exhibition at the Theatre in Privas, associated with the Le Partage des Eaux in the Ardeche region. This is why I also talk about long-term relationship with artists. This ranges from in situ exhibition projects, then ex situ to acquisition and/or publication, like a thread getting ever longer.

This approach is, of course, different from the “Nomad Galleries” whose brief is to enable young artists coming from Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes art schools to have a formative experience in the region.

How do you see the place of contemporary art and the predominant place of Lyon in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region? Have you re-defined some of your missions, or developed new partnerships after the merger of these two regions in 2015?

The issue of dissemination doesn’t seem to me to be first and foremost a curatorial one: it is above all connected with the educational question. The area is large, it’s true, but there are two of us to share it: the FRAC Auvergne and the IAC. In recent years, we have embarked on a relation of exchange with successive presentations of our collections. From now on, we’ll be getting into a phase where we share out our respective roles over the region. For example, one of our projects is to move the “Nomad Galleries 2020” to Auvergne. Furthermore, faced with the issue of remote areas, we are preparing a system titled “A territory in three tempos”, which will unfold over a lengthy period, somewhere between 18 months and three years, in a territory known as a “white zone”. By way of a gradual process, via the collection, we are inviting young artists to take up production residencies in connection with the inhabitants of this “zone”. Here, above all, it is a matter of human adventure and time. In due course, we imagine that these artists will also be able to devise a project for an ephemeral work in Villeurbanne’s urban space. To be in this relation between near and far, it is more important than ever to be rooted somewhere, and in this instance, here, in Villeurbanne.

In 2016 the IAC Foundation was created, under the aegis of the Bullukian Foundation. Why did you feel a need to create this organization? Can you tell us how it operates and about its links with the IAC’s activities?

This foundation works like an endowment fund and its brief is to associate patrons and sponsors with our programmes, both companies (BREMENS | ASSOCIES | NOTAIRES in 2017) and private individuals. For example, the IAC is proposing once a year to hold an exhibition within a business. The liaison with corporate publics and the expression of civil society are part of the IAC’s DNA.

Does this anniversary mark a turning point in your programming? How does taking the IAC’s history into account help you to think about the present? You’ve just organized the Katinka Bock show titled “Radio”, the third part of the cycle Tomorrow’s Sculpture, in collaboration with the Mudam Luxembourg and the Kunst Museum Winterthur. Are your upcoming projects being planned, like this one, on an international scale?

Celebrating the IAC’s 40th anniversary involves a desire to remind younger generations about the art centre’s history, pioneer that it is, and cousin of Le Consortium and the CAPC. I simply suggested that we take an instant photograph, without changing our programming. The past is a basis, one that is always active, but our challenge is nevertheless to be always in a process of moving forward. It’s a way of remembering the empirical dimension of situations at that time, the fragility of these art centres, and questioning their permanence. As far as international programming is concerned, the Daniel Steegmann Mangrané show this year will give rise to a joint publication with Hangar Bicocca of Milan, and “Rendez-vous” still exists within the Lyon Contemporary Art Biennial, with artists from the Rhône-Alpes region and international artists, but in a more concentrated and more substantial form.

This year’s main project is to give material form to the Lab by offering it premises in the heart of the IAC’s exhibition rooms, except during the period (first semester) devoted to a project involving all the spaces, with activation times, and use times. In tandem, the satellite Rendez-vous will work more on the issue of the urban territory under construction with Villeurbanne.

Not many solo shows were devoted to women artists at the IAC for ten years. But more recently you’ve organized several, starting with the Ann Veronica Janssens exhibition in 2017. Why’s this?

Until recently, you could be proactive and assert the principle of exhibiting women artists, or you could choose to be above all involved in artistic demand. Well it seems to me that, nowadays, the question is no longer being raised in these terms, at least that’s what I hope. Women artists are finally here, and really here. However, we must obviously remain alert. It’s true that in immersive systems and systems involving relations to space, which I used to be interested in, we find many more male activities, to such an extent that Ann Veronica Janssens was, for a long time, an unusual figure, but this is finally changing.

How do you imagine the IAC in ten years? What developments would you like to introduce?

For me, it’s not quite right to talk in terms of this time-frame. That’s even a choice: we are in a phase of change. Predetermining things beyond five years seems risky to me and contrary to our quintessence: we are not a museum. To start with, I’d like to enlarge the Lab and increase its international relations with, for example, the ZKM [Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie Karlsruhe], and MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology], and set up residencies for artists and researchers at the IAC.

Image on top: Ann Veronica Janssens, « mars », 03 – 05.2017. © Photo : Blaise Adilon.

Related articles

Céline Poulin

by Andréanne Béguin

Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Interview with Warren Neidich

by Yves Citton