NN-A NN-A NN-A

“NN-A NN-A NN-A” borrows its manner from concrete poetry to evoke what its three curators—Gunnar B. Kvaran, Therese Möllenhoff and Hanne Beate Ueland—working at the Astrup Fearnley Museet in Oslo call the new Norwegian abstraction.

Exactly a hundred years after the official arrival of abstract painting, by way of the hanging of a certain Black Square high up on a wall in a gallery in St. Petersburg, they are taking a close look at its topicality in the work of young artists from their country, with all the ambiguities that this implies. If there is in fact a connection, today’s abstraction has nevertheless passed through the filter of a century of modern art before being rekindled by the yardstick of contemporary concepts in artworks, some of which Therese Möllenhoff describes as neo-modernist. Whereas postmodern de-hierarchization and levelling have successfully relieved it of its ideals, not to say the theories which underpinned it, is abstraction now no more than a reference, a purely visual category? The question was put to Gunnar B. Kvaran and Olve Sande, one of the artists supposedly representing this new abstraction. Their two relatively contrasting viewpoints do in any event trace the space for a line of thinking which we might sum up as follows: does the abstraction that we are nowadays encountering in the work of young artists resemble abstraction?

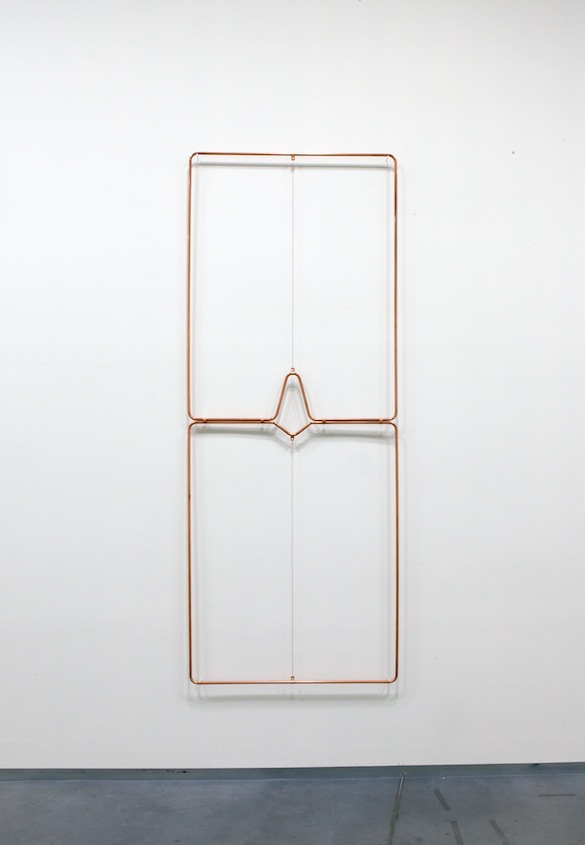

Johanne Hestvold, EV VU, 2014. Copper, 230 × 90 cm.

Courtesy Johanne Hestvold. Photo : Astrup Fearnley Museet.

Interview with Gunnar B. Kvaran

Since 2005, with “Uncertain States of America”, together with Hans Ulrich Obrist and other curators, you have organized a certain number of shows focusing on young art scenes in specific regions such as the United States, China, India, Brazil and, most recently, Europe1. Based on your experience, what are we to understand now by the term “art scene”, knowing that artists are more mobile than ever ?

In the last decades, the western notion of art has become a universal language. But despite the ever increasing globalization, the world and different civilizations and cultures have not yet become one thing. Even though artists in different parts of the world adopt similar ways of art making, they are still rooted in the geo-cultural environment by their language, their history, their culture in a broad sense and even the climate. This is of course more visible when we compare Chinese, Japanese and Indian artists to European and American artists. It’s clear that a great artist like Huang Yong Ping has important “Chinese-ness” in his works. The “art scenes” are not only where art works are being produced but a place in a certain time and space, where you have different kinds of ingredients that condition the art making. And then it’s also the question about the local artistic and cultural infrastructure—art schools, museum, galleries— which are not the same in these different parts of the world. No, I think we are still far away from the “one global art scene”.

This matter of artists’ mobility within a territory is actually being raised with a greater keenness and intensity where Europe is concerned. So is the term “European art scene” really possible and relevant with regard to what is asserted by the press release for the show “Europe-Europe” where you were one of the curators, to wit: “Europe is a territory that is more polycentric than ever before, where artists come and go from one city to another, without any longer being attached to their home countries or determined by the canons and rules that have long defined and structured the various European Art Nations until now”?

The question of art scenes in Europe is of course a more subtle question. In the last years we have witnessed greater mobility of artists within Europe in terms of physical travelling but also in terms of virtual travelling. The access, through Internet, to information and the possibility of informing the other has become overwhelming. This is especially visible in central and Northern Europe. There is a remarkable flow of artist travellers between cities like Berlin, Brussels, Paris, London and Scandinavia in general. This means that there is no longer one city, one art scene dominating the rest of Europe. In Europe today there are many art scenes which are anchored in their cultural history and environment, but at the same time they are communicating between each other. In terms of modern and contemporary art, the European continent is exceptionally rich and multiple when it comes to culture and artistic production shaped by local traditions, history and languages. In fact in Europe we have many strong art scenes, which are stable and solid but moving, and then we have individual artists who travel from one art scene to another bringing with them new influences, to a certain degree, and of course absorbing other kinds of new possibilities. But beyond the question of art scenes one could say that European contemporary artists are less concerned by their “national identity” than before. They are not really representing a nation.

Exhibition view of «NN-A NN-A NN-A», Astrup Fearnley Museet, Oslo. On the wall, from left: Fredrik Værslev, Ivan Galuzin; on the floor: Tiril Hasselknippe. Photo : Astrup Fearnley Museet.

After “ Lights on Norwegian Contemporary Art” in 2008, you have just opened “NN-A NN-A NN-A2 » for “New Norwegian Abstraction” ; talking about “Europe-Europe”, you say: “… we had to give up some of our power of definition in order to achieve that and to uncover the true nature of the European art scene3”. What curatorial decision did you take with your associates for this new exhibition ?

The European art scene is perhaps even more rich and multiple than those already mentioned, since Europe is a continent composed of many different nations, languages and cultures. Because of the complexity of these different artistic scenes, and due to the scale of the project, the curatorial team decided to work with an ‘organic curatorial model’, creating an exhibition that can change and develop over time. From the beginning, the exhibition “EUROPE EUROPE” has been conceived to take place in different museums over the years to come. The ‘rule of the game’ was that the curators would choose two artists and one correspondent (a local art expert) from each of the cities. The correspondent was invited to contribute to the exhibition by suggesting two additional artists from that city to be included in the selection, and by contributing to the catalogue with an introduction about the art scene in which he or she currently works. For the duration of the exhibition, eight artist-run-spaces from the eight cities, chosen in dialogue with the correspondents, were invited to present a week-long special project in a separate space within the show. The intention of this rule of the game was to penetrate the different layers of artistic production within these different art scenes to get as close as we could to the emerging artists and the real nature of the art scene in question.

“NN-A NN-A NN-A” is a different exhibition project and the curatorial model is more traditional. Over the last few years we had noticed that more and more emerging Norwegian artists were working around the notion of abstraction. We did our research and discovered quite a lot of young artists revisiting the possibilities of a new abstraction. We choose 17 artists, 6 men and 11 women. Quite early on in our research, we understood that most of them were concerned with experimenting with materials and materiality, using unusual equipment and inventing or appropriating tools to create new possibilities of writing and expression. Others are more interested in the construction and deconstruction of forms related to space and the notion of time.

“NN-A NN-A NN-A” seems to be based on the fact that you use abstraction as one form among others, like an archive from which to draw references that are more formal than conceptual, before filling them with new contents. From now on, in your book, is this new abstraction just a visual scheme ?

On the first level of our reading, the works of these artists seem to confirm that they are the great-grand-children of modernism, a vision of the world that gained its position during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It is quite obvious, however, that it is not only historical abstraction that has a presence within the works of these young artists. Minimalism and Conceptualism are obviously also factors. One can see and understand this more clearly within their working process, and expressed through their texts, than in the final works themselves. And more than ever before, the titles of the works play an interesting role, revealing the artists’ intentions and the close connection between language and abstraction, a connection that is of course intellectual and rational, underlying and fundamental, language being a symbolic system. One can also see in these works the shadow of postmodernism, which has been extremely influential in the last few decades. Of course, this is in a way a contradiction, but one that demonstrates the strangeness of the situation for many international artists, including Norwegians, when it comes to their relationship with historical references. Is it about finding new means of expression, inventing and opening up new possibilities, rather than working with displaced and eternally returning references, ideas as images, where the origins are often long gone or have ceased to matter? But their paintings are not born from the same intentions as those of fifty or sixty years ago. The recitation of history and its successive ruptures have seen to that. In the last ten years, young artists have included art-historical references in their flow of found objects without any qualms, seeing them simply as raw materials for the making of art. Often this brings their works close to the “image-as-abstraction” approach, in which images are considered as excerpts of a whole, which raises the question of representation and abstraction, or simply the representation of abstraction. The widespread and ongoing recapitulation of abstract forms in sculptures and paintings that frequently reveals itself in the new media means that disrupting the linearity of history becomes the inherent subject of these works. The artists’ relationship with history is quite relaxed, and they have no problem in acknowledging their art-historical references or influences. In fact, as children of the Internet (and not only the great-grand-children of modernism), they have broken away from the linearity of history, and are simultaneously in the past and the present, helping themselves to art-historical imagery from the abundant sources of information on the Internet, without passing judgment and simply creating their own work and space.

1 “China Power Station”, “Indian Highway”, “Imagine Brazil”, “Europe-Europe”…

2 “NN-A NN-A NN-A”, Astrup Fearnley Museet, Oslo, from 13.02. to 3.05.2015. Curated by: Gunnar B. Kvaran, Therese Möllenhoff and Hanne Beate Ueland. With : Ann Iren Buan, Petter Buhagen, Marie Buskov, Ida Ekblad, Ivan Galuzin, Tiril Hasselknippe, Johanne Hestvold, Marianne Hurum, Marte Johnslien, Henrik Olai Kaarstein, Camilla Løw, Anders Sletvold Moe, Magnhild Øen Nordahl, Aurora Passero, Olve Sande, Fredrik Værslev, and Emma Ilja Wyller.

3 Cf. André Gali, “The Energy Within the Crisis”, in Kunstforum n°4, 2014, p. 72.

Interview with Olve Sande

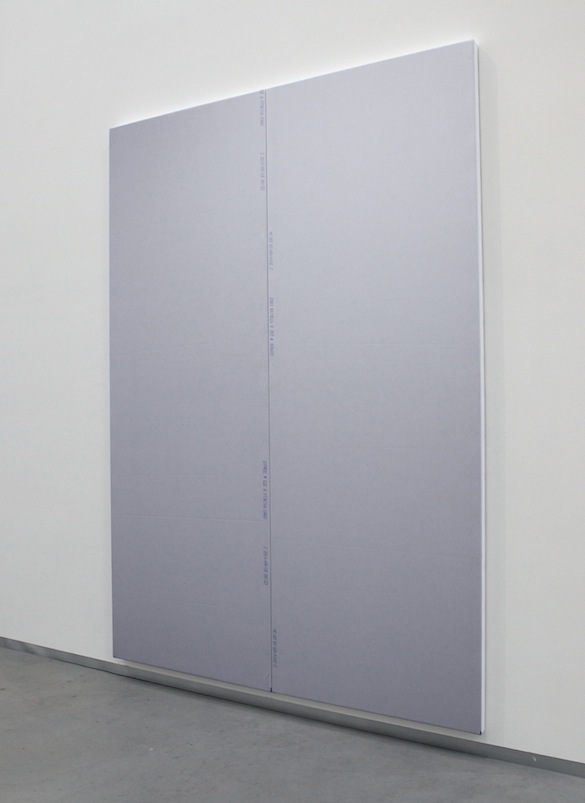

Olve Sande, Plasterboard Flats (detail), 2015. Exhibition view of « NN-A NN-A NN-A », Astrup Fearnley Museet, Oslo. Photo : Astrup Fearnley Museet. Courtesy Olve Sande ; Galerie Antoine Levi, Paris.

As an artist, what are your thoughts about appearing in a group show titled “New Norwegian Abstraction” ?

My participation in this show and the whole process leading up to it has of course made me more conscious of what role abstraction plays in my practice, and how my idea of abstraction relates to other ideas of abstraction. I think one of the important aspects of the show is the discussion it has triggered about the term abstraction. Since the museum curators started their research for the show, there’s been a lot of talk between artists about what abstraction actually means. It turns out very few actually know what is meant by this term… There is a huge difference between abstraction as a style and movement and abstraction as an idea. It’s quite easy to define it as a style, but it gets more tricky when you see it as a concept.

To many people, abstract art is a term you use when you are not able to recognize the subject matter of a painting. But actually, when you think about it, abstract expressionist painting is less about abstraction than a photo realist portrait would be, because it is not an abstraction of anything. Action painting is in the end a very concrete act with no referent.

It is a term that constantly contradicts itself, and the more you talk about it, the more difficult it becomes to define. An abstraction could both be an abstract of a situation, of the essential qualities of a thing, it could be whatever is not representational, but it could also be very concrete. The word “chair” is an abstraction of the chair itself, but it is also very concrete. Most of the works in the show are non-representational, but then again, you have works like my own that is hyper representational and has very little to do with abstract painting.

What does the term “New abstraction” mean to you ?

I don’t put too much in that phrase and I tend to forget that the word “new” is in the title. For me, this is a show about abstraction. It is new because the artists are young and the artworks are new, but I’m not sure if the interest in abstraction is any more present now than ten years ago… If you reduce the idea of abstraction to a painterly style or fashion, then perhaps, but this is the least interesting use of the term. To me, abstraction is more about an artistic approach than it is about figurative or non-figurative works of art; it stands as an opposition to the conceptual, synthetic work of art. It’s a way of insisting on the importance of something that is impossible to describe, or rather something that would be broken the moment you try to describe it. Abstraction takes time. It’s about getting to the core of things, and has a lot to do with repetition and failure. It is about finding a way of communicating something that would seem dull and lifeless if you were to explain it. It is about living with something and spending time with it, not to pick it apart, but to gradually understand what it is about, and to slowly realize how to express it without describing it. To me, it has a lot to do with the way poetry works.

Olve Sande, Correspondence (280 x 115 cm), 2014. Paint absorbent felt on stretcher, 280 x 115 cm. Installation view, Bikini, Lyon. Courtesy Olve Sande ; Galerie Antoine Levi, Paris.

Sixty years ago, Clement Greenberg famously wrote that : “From Giotto to Courbet, the painter’s first task had been to hollow out an illusion of three-dimensional space on a flat surface. One looked through this surface as through a proscenium onto a stage. Modernism has rendered this stage shallower and shallower until now its backdrop has become the same as its curtain, which has now become all the painter has left to work on. […] The picture has now become an entity belonging to the same order of space as our bodies ; it is no longer the vehicle of an imagined equivalent of that order.”1 It’s difficult not to see your work, and especially the piece you produced for NN-A NN-A NN-A, as a direct answer to that statement… Could you tell me more about the way this particular work seems to be a cornerstone in your way of thinking about the relation you set up between architecture and literature ?

It is definitely important to me that the artwork is of the same order as the things normally surrounding us.

For the Plasterboard Flats piece shown in the Astrup Fearnley Museet, I would like each panel to be treated as if it were actual plasterboard, taken from a stack of sheets of plasterboard, all apparently similar but also obviously individual objects. The work is neither seven artworks nor one artwork; it is neither unique works nor a definite series.

That said, what interests me in plasterboard is not its material qualities, but the plasterboard as an idea: the idea of building, the act of constructing, new spaces, potential narratives, etc. I don’t want the works to be specific objects, but I want them to function as placeholders for a general situation, so in a way, these works are not in the realm of ordinary things.

I wanted to make a representation of the plasterboard rather than to use actual sheets of plasterboard, like you would on a theatre stage, hoping this could make the idea of the plasterboard clearer. I don’t want the artwork to be supported by or depending on its material qualities.

A while back I did a project where I worked with the painters in a painters’ workshop of a theatre. When I asked them why they painted the stage floors instead of using actual materials, they told me that, from a distance, a stage floor painted like linoleum looks more like linoleum than if you use the actual linoleum. This made total sense to me. Why use the real material if it is the idea about the material you’re interested in? So, as I realized what interested me in this project was the idea of the plasterboards and not the plasterboards as a material, I decided to present them as you would do it in the theatre. I wanted to make them look more like plasterboards than actual plasterboards.

What interests me in building materials is the idea of spaces and their potential for narrative. Perhaps potential “situations” would be more precise. I’m interested in the idea of a narrative in the same way as I’m interested in the idea of architecture rather than making actual buildings. The moment you finish constructing a room, when you have painted all the walls and put in all your furniture, the imaginative potential of that space would be lost to me. This is why I’ve been working with raw plasterboard and paint absorbent felt, because these materials are only visible in the imaginative process of renovating a room. In this process, you’re setting up the structural conditions for a series of specific situations. When you start painting your walls, you gradually understand how it will turn out and the narrative potential of that space decreases the way Greenberg’s stage gets shallower and shallower.

So I want my works to be both the stage curtain and the backdrop. The empty stage is an open-ended architecture, a general situation that could contain any specific situation. If modernist painting was reduced to the curtain of the stage, I want to separate the backdrop from the curtain, to pull it back to open up the empty stage again. Still, I would like the curtain to be there, so I would cut out window sized apertures from the stage curtain and pin them to the back wall, as a backdrop. This opens up a space between the pierced curtain and the blind windows in the back.

I’ve always been more interested in the literary potential of architecture and the architectural potential of literature; I find the empty stage much more interesting than any actual play; I find a closed window more interesting than a window with a view.

1 Clement Greenberg, “Abstract, Representational, and so forth” (1954), in Art and Culture, critical essays, Boston, Beacon Press, 1961.

(Image on top: Magnhild Øen Nordhal, Seksagesimal, 2015. Courtesy Magnhild Øen Nordhal. Photo: Astrup Fearnley Museet.)

- From the issue: 73

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Paolo Cirio, Sylvain Darrifourcq, Computer Grrrls, Franz Wanner, Jonas Lund,

Related articles

Céline Poulin

by Andréanne Béguin

Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Interview with Warren Neidich

by Yves Citton