Mondes nouveaux

“Mondes Nouveaux” (New Worlds) is a programme developed by the French Culture Ministry in 2021 whose aim is to provide financial support for artists to carry out projects destined mainly toward the valorisation of national heritage (including outdoor sites and historical monuments). A spate of these projects were inaugurated during the summer of 2022, consisting mainly of subtle interventions which took the form of ephemeral in-situ works at open-air sites such as the Pointe du Raz, the coast of Normandy, Château d’If, and also include historical monuments. As for some of the other projects—more difficult to produce due to their complex logistical nature and lengthier installation time-frames (with additional film or literary elements, or where the works themselves are complex)—they will be carried out over the course of the coming year, giving us the opportunity to gather enough information to understand the overall project—grandiose in scale with its no less than 264 projects…

As Claire Moulène speculates in an editorial published last June in Libération, what sort of landscape will take shape through the “Mondes Nouveaux” projects? In her article the journalist points out that “Mondes Nouveaux” was created as another, already existing project was being lauded by the Culture Ministry—“Nouveaux Commanditaires,” New Sponsors, which is on the opposite end of the spectrum from “Mondes Nouveaux”. While this newer project has—perhaps a bit suddenly—appeared on the scene, “Nouveaux Commanditaires” is by contrast the product of numerous, in-depth dialogues with different actors involved in the process. More importantly, the Commanditaires projects are the outcome of desires expressed by the inhabitants of a given region, or at least by those directly linked to the inhabitants. This program allows them to participate directly in the process of sponsoring an artwork. If the “Mondes Nouveaux” projects are lacking in something it is this—a direct relationship with the local populations at each site. One of the collateral effects of this lack of local roots has been the difficulty the recipients of the bursary have had in establishing partners in the actual carrying out of the projects once on location. Performances, installations and concerts in particular have been affected by this aspect, as many of the outdoor sites are completely devoid of the type of logistical conditions necessary for these types of interventions. The same challenge applies to large-scale installations of which there are many in “Mondes Nouveaux”, and for which many of the sites are completely unprepared.

“Mondes Nouveaux” also raises a number of other no less fundamental questions; for example, should projects be held to a “citizen-oriented” standard which takes into account the wishes of local residents? Can they be expected to project a relatively collaborative and/or participatory image, leaving space for the opinions and tastes of the general public, outside of which the work may risk being perceived as an import project? Projects like that of Cyprien Gaillard, for example, run the risk of rubbing artists the wrong way who may be struggling to raise the funds to carry out their own projects…Is it really necessary to fly a Canadair to empty the fountains of Versailles in order to put out a fire in some undisclosed locale? In the midst of mega-wildfires and calls for economic sobriety, the project exudes a slightly out-of-step extravagance.

But let’s be frank— after a quick overview of this long list of projects, most of them are indeed dedicated to citizen-based, ecological-minded, landscape-informed preoccupations; they are concerned with issues related to the conservation and valorisation of industrial, coastal, mountainous and of course, cultural heritage sites including castles and other monumental sites. In addition to this and on an entirely different wavelength, many are concerned with issues related to language, local culture and decolonialisation, as several projects in Martinique, Guadeloupe, Réunion and Guyana attest. These projects focus their attention on the specific situations of regions which are far-removed from the urban centre and face crises of all sorts on a regular basis. The projects in these regions often deal with the singularities and difficulties experienced there.

Most of the “Mondes Nouveaux” projects have a particularly positive glow, giving prominence to more “sustainable” proposals which originated in lengthy relationships with the inhabitants of the neighbourhoods and surrounding districts. Others involve the participation of local actors, as is the case with Erwan Mahéo’s project, which attempts to restore the “voice” of a defunct “siren”—as refers to the seaside structures whose foghorn has been rendered obsolete by technological developments. This open installation calls for the awakening of the collective memory of the Belle Isle community with regard to rescue and safety techniques, while also participating in the restoration of emblematic coastal architectural forms in Brittany such as lighthouses and beacons (see detail). There are many examples of projects which focus on the restoration or revivification of singular projects; Théo Audoire’s project revisits a largely forgotten chapter in French industrial history that went flop—that of the industrial flamboyance of the 1970s as exemplified by the aérotrain (see detail). Élise Molinard, Antoine Gouachon and Giacomo Monari revisit with their projects a quintessentially Corsican structure, the pagliaghju—a sheepherders’ hut made with dry rocks and seen through a designer’s lens; the projects are also an opportunity to explore ancestral traditions while also potentially reconnecting inhabitants with a territory—Corsica—whose landscape has remained relatively untouched. Overall, there are untold numbers of projects linking heritage—whether industrial or simply architectural—with memory and revisitation/resurgence via design updates.

Not to mention the multitude of proposals featuring the coast as a backdrop; these projects make the most of the exceptional abundance existing in coastal regions in France, from Corsica to Normandy, including Brittany, which is particularly well-represented. One example is Hoël Duret’s project on the Pointe de Raz which channels Mad Max, bivouac-style (see detail).

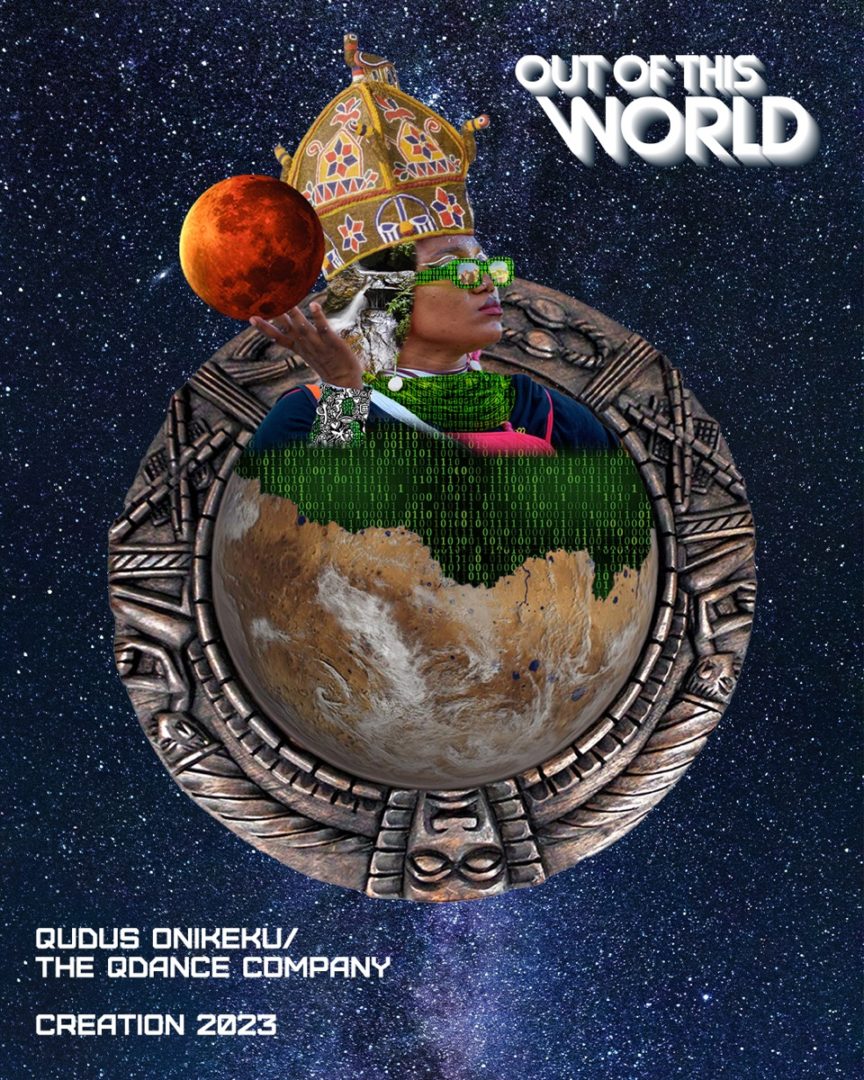

A particularly diverse variety of forms and the highlighting of transciplinary practices are both salient aspects of the “Mondes Nouveaux”initiative. It is especially refreshing to see so many instances of literary and poetic production (see detail Laura Vasquez and Laurent Derobert), as well as of dance, which has been given a prominent position (see detail Qudus Onikeku). However, more “cultural” issues have been far from ignored—in an Ernest Breleur and Stéphanie Brossard project, pre-eminence is given to language in order to express the consequences of the pandemic and globalisation on living things. Through the writings of Patrick Chamoiseau and Édouard Glissant, the artists promote a thoroughly renewed approach which addresses issues typically reserved for the scientific community (see detail).

Other more difficult-to-categorise projects as well as the more recent preoccupations of younger artists are also given pride of place. Léa Brudier’s project, for example, pays close attention to the olfactory sense, which is generally not given much prominence in the art world, dedicated as it is nearly exclusively to vision and audition. Also worth noting is the importance of science fiction and other progressive types of thought; one project in particular by Lucas Monjo focusses on these themes with the energy and enthusiasm of a new generation whose view on gender has become more nuanced. He revisits a Biblical theme in which two mythological figures named David and Jonathan are presumed to be homosexual—all against the background of an alien invasion—in a jubilatory way (see detail).

Yet another aspect of “Mondes Nouveaux” is one which provides the setting and occasion for the craziest ideas, while not necessarily requiring excessive expenditure. For Giraud and Siboni, this means the purchase of a stretch of land smack in the middle of the Millevaches plateau in order to carry out a collective, long-term (1000 years!) artwork, with the objective of uniting artists, scientists, poet-musicians, botanists, etc., bringing back to life an idea which has long been pronounced dead and whose name is quite simply “utopia” (see detail).

With regard to the question we posed at the outset regarding the landscape which would eventually emerge through “Mondes Nouveaux”, there is no doubt that it attempts to present a kind of overview of contemporary art today, with all of its flexibility and porosity between disciplines, giving new meaning to these terms. “Mondes Nouveaux” is remarkable in that it provides recognition for younger, emerging artists, who incontestably bring a breath of fresh air to the landscape of contemporary art. Nonetheless, at a time when art centres and associations encounter numerous difficulties in keeping their doors open with things running smoothly, the sudden influx of funding for projects which were put into place under rushed circumstances has inevitably raised a certain number of eyebrows. However, the 30 million euros earmarked for “Mondes Nouveaux” do make up a portion of the post- COVID-19 recovery package, having been attributed as a means of support for artists who found themselves in dire circumstances due to the pandemic. “Mondes Nouveaux” can be viewed as a representation of a kind of creative and imaginative utopia which allows for the existence of all types of multidisciplinary approaches, a kind of curatorial dream in which suddenly all possibilities become available as well as the funding to make projects—from the most deserving to the craziest—happen.

Head image : Erwan Maheo, la Sirène, Belle-Île.

- From the issue: 102

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Kristina Solomoukha, Jean-Pascal Flavien,

Related articles

The Round

by David Evrard

Lili Reynaud Dewar

by Dorothée Dupuis

Thomas Teurlai

by Marianne Derrien