Zoe Leonard: Survey

The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, Los Angeles, 11.11.2018 – 25.03.2019

by Eliza Levinson

In Los Angeles, to age openly is considered shameful. The city, pockmarked with billboards of beaming doctors and Botox, gleefully encourages passing drivers to disguise their traitorous flesh with its skin folds and yellowed teeth, crows’ feet and stretch marks. Los Angeles itself is ever in the midst of its own face lift, knocking down scuffed bricks and dingy white stucco for crisp clear glass to rise, the lavish phoenix from the ashes. And what, then, becomes of the truth, bowled over with concrete wrecking ball?

As Zoe Leonard makes clear in her body of work, now in a retrospective entitled “Survey” at MOCA, Los Angeles, what has been zapped, plastered, and tucked from the annals of history is scarred nonetheless. In Leonard’s work, it is the concrete-covered window of the anonymous city or the yellowed postcard of the unnamed tourist that takes centre stage, lined up and framed in an unconventional ode to memory. While her specific projects consider a range of subjects—archives, literature, nature among them—Leonard returns over and over to the peculiar poetry of use: the employment of an object over time by the mobile, mysterious Owner.

Robert (2001) takes this concept literally. Here, Leonard stacks ten found suitcases, a visual motif she returns to throughout the exhibition. The suitcases are fairly unremarkable, if somewhat retro—boxy variations on brown, black, and beige; a sort of larger briefcase, with inflexible handles and gold or silver clasps. Each suitcase is unique, with dangling string remnants of long-lost luggage tags and rubbed-off fabric. One in particular stands out, right in the tower’s middle: the largest, squarest suitcase of the bunch, shiny black with brown trim and the initials M.M. carved dramatically into the object’s right side. The sharp, straight lines of the self-referential engraving embody both the specificity and the facelessness of the aged suitcase: a marker of memory, floating, only half-tethered to a still-elusive identity. By including this valise in a stack of nine others, Leonard folds the individualised object back into conversation with the multitude, an experiment in opposites the artist will explore throughout her body of work.

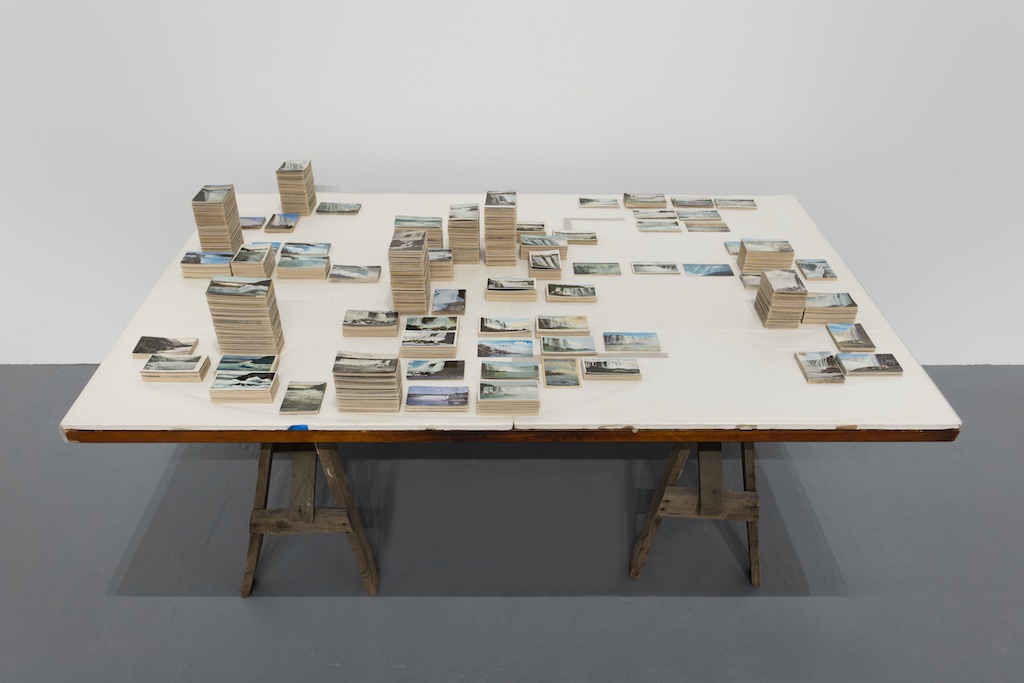

In a work entitled Survey (2009-2012), Leonard features 6,266 found vintage postcards from between 1900 and 1970, each a different depiction of the famous North American landmark Niagara Falls. In this iteration, Leonard’s postcards have been arranged in about 65 piles on a mid-size table cloaked in white wax paper. The cards range stylistically from pastel-hued, yellow-tinged watercolours to black-and-white photographs, some stamped at the front, some with type- or handwritten captions; all softened at the edges from time. The postcards, though with a shared subject, have been clustered based on vantage point, ultimately forming a shattered lens through which to see a kitsch mosaic of a distant place: from above, below, the side. The water crashes, distant, white foam churning, streaks of white clouds in clear blue skies.

As with Robert, Leonard uses time-worn relics of travel as a means of conjuring ideas of movement, ownership, and temporality. The postcard is a particularly fleeting possession, at least for the buyer, more often purchased for the sake of evoking an experience for someone else—that is to say, a gesture of see what I saw? for someone who was not there. With deceptive simplicity, the Niagara Falls postcard collection utilises the expanse of cheap touristic memorabilia of a singular location as a means of reinforcing the perceived value of its subject. Why else would so many visitors feel so inclined to purchase the waterfall’s likeness to pass along to their loved ones? As such, Leonard encourages the viewer to question why the falls receive such adulation, as well as, once again, the universal subject (the national monument; the mass-produced postcard) wrought personal (chosen, inscribed, sent).

Leonard takes her political inquiries further and more personal with one of her most iconic works, I want a president (1992). In this, the artist has typewritten an open letter on translucent onionskin paper wherein she envisions her ideal leader of the United States: “a dyke,” “a person with aids [sic],” “who has stood on line at the clinic, at the dmv, at the welfare office and has been unemployed and payed off [sic] and sexually harrassed [sic] and gaybashed and deported,” “who… had a cross burned on their lawn and survived rape,” “who has committed civil disobedience.” The artist concludes:

And I want to know why this isn’t possible. I want to know why we started learning somewhere down the line that a president is always a clown: always a john and never a hooker. Always a boss and never a worker, always a liar, always a thief and never caught.

These lines are, of course, particularly salient in 2019, lines this reviewer will read the day after a sardonic, white-suit-wearing Nancy Pelosi extends patronizing applause to our country’s latest clown-in-chief at the State of the Union. Though I want a president is less conceptually dense than the Niagara Falls photographs and less abstract than Robert, Leonard’s preserves her persistent question (“And I want to know why this isn’t possible. I want to know why we started learning somewhere down the line”)—her fascination with hegemony and pedagogy, her close scrutiny of that which undergirds our everyday lives. The staying power of I want a president is a testament to the consistency of Leonard’s artistic thesis: straddling the personal and the universal—the complaints of the invisible everyman, brought against the all-too-recognisable, ever-shifting Politician—, keeping her message evergreen; wrinkles, tears, and all.

All images: Zoe Leonard: Survey, The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. Courtesy MOCA, Los Angeles. Photos : Brian Forrest.

Related articles

Ho Tzu Nyen

by Gabriela Anco

Hilma af Klint

by Patrice Joly

Plaza Foundation

by Andrea Rodriguez