Author as producer : Katia Kameli and her books of images for re-writing History

Elle a allumé le vif du passé

Frac Provence-Alpes Côte d’Azur, Marseille, 20.05-19.07.2021

As a possible heir to the thinking of Walter Benjamin who, caught up in the full rise of Nazism, laid claim to the need for the artist to assert his position in terms of class and organize his activities together with a materialist social line of thought by conceiving his work in “relation to the means of production and its technique”1, Katia Kameli is developing a body of work that deconstructs the clichés of History using a methodical analysis of what makes it: words and images. Like the development of a negative film, she reveals a postcolonial memory made up of manipulations, comparisons, and concealments. This Franco-Algerian artist sets herself in a research project situated somewhere between photographs, films and installations, which questions and spoils historical and cultural facts which have informed her daily round, constructed in the Mediterranean interstice. As part of Saison Africa 2020, held at the FRAC PACA, her exhibition titled “Elle a allumé le vif du passé/She has Ignited the Stuff of the Past”, curated by Eva Barois de Caevel, proposes a re-evaluation of History and its writings.

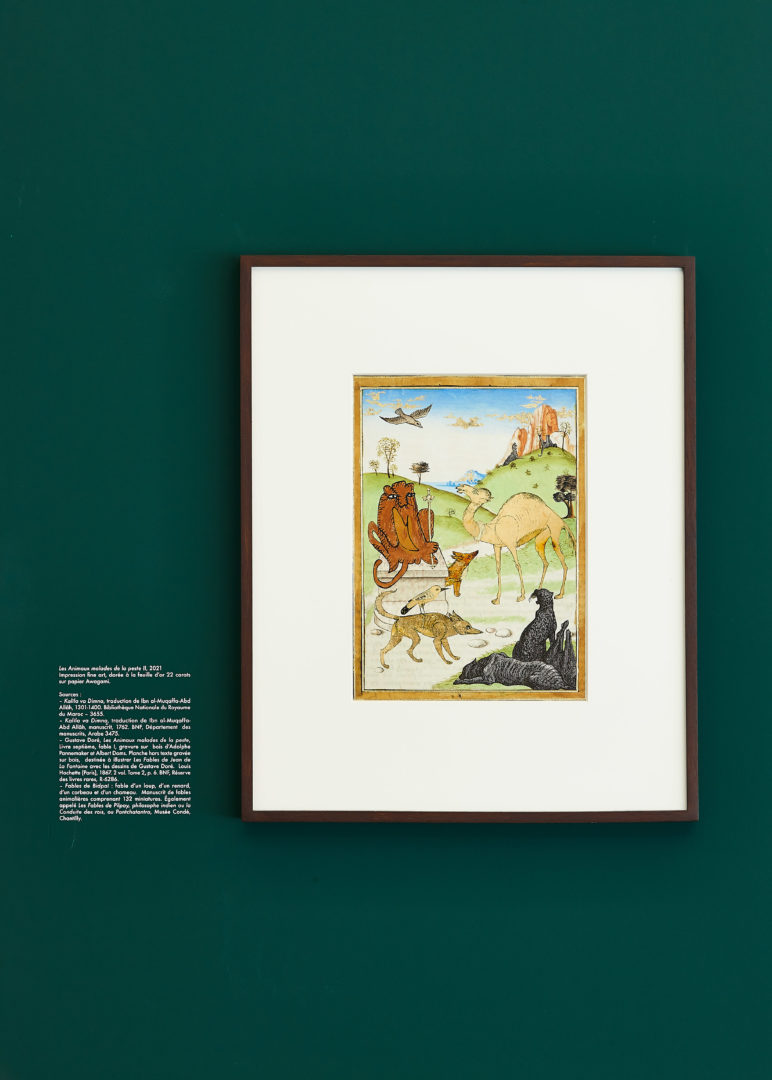

Filling the two levels of the Marseille venue, the exhibition brings together two proposals, titled Stream of stories and Le Roman algérien/The Algerian Novel, chap. 1, 2 and 3. The first is an installation devised specifically for the FRAC (Regional Contemporary Art Collection); it explores the oriental origins of fables, offering a wholesome counterpoint to the French representation of La Fontaine’s favourite genre. As a sculptural book opening onto space, like a point of intersection, and encounter, the installation, which is the green colour of a school (black)board, attempts to deconstruct the western canon of a fable which is merely the product of a Graeco-Latin culture, by way of the legacy of Aesop and Phaedra. Combining collages, silkscreen prints, facsimiles of original manuscripts held at the BNF and the Royal Library in Morocco, video, and a sound system, Stream of stories retraces the history of the genre with an emphasis on the circulation of texts based on the writing of the 3rd century BCE Pañchatantra, its translation into Pahlavi in the 6th century AD, and its version in Arabic, some 200 years later, under the title Kalila wa Dimna. While the work is ground-breaking and recognized in the mediaeval Arab world, the artist laments the erasure of this genealogy when the fable is taught in French schools.

The setting thus echoes the host of voices which inform La Fontaine’s œuvre, and which do not, however, feature in school textbooks: an impression of hubbub comes across amid the sound of the two videos presenting the actress Clara Chabalier and various researchers, and the voice of Chloé Delaume, that can be heard in the small space where the author’s words ring out as she reads a text written specially for the show: On nous l’a dit et on l’a cru/That’s what we were told and that’s what we believed. A busy cacophony which calls for off-centering and discrepancy, and for a de-hierachization of knowledge and works, as defined by Lionel Ruffel in his book Brouhaha. Les Mondes contemporains (Verdier, 2016)…, polyphony incarnates the essence of Katia Kameli’s installation : the idea that the plurality of voices, cultural transfers and translation lie at the root of all culture, but also all cultural politics. This thesis is incidentally championed in post-colonial studies by Franz Fanon, Edward Said, Gayatri Spivak and Homi Bhabah—whose Les Lieux de la culture. Une théorie postcoloniale appears to be a quintessential work for the artist.

The arbitrariness of literary history is thus duplicated by a policy of rendering the contributions of Indian, Persian and Arabic literature invisible to the 17th century classic fable. Like a palimpsest that has, in the end of the day, been more erased than planned to tally with a fantasized western canon, the fable is here reinstated from its many different origins, which would benefit from being discussed in the classroom in order to help new generations become aware of it… –and in particular those resulting from immigration–, the circulation of texts and the wealth of foreign cultures and of the “oriental world”, to borrow a term which can only be constructed in contrast with the West. So what Katia Kameli incarnates in her work is a whole line of thinking about translation: from the works of Emily Apter, and in particular Zones de traduction, to those of Tiphaine Samoyault, in the most recent Traduction et violence. If, for the artist, everything is translation and all creative people are merely the interpreters of something that already exists, this stance also takes into account the agonistic forces which shape the act of translating: as a process of domination consisting of appropriation, spoliation and reduction, translation may also become ethical, as positive openness which permits the construction of the common. Provided that (literary) imperialism is replaced by a transnationalism.

At the heart of Katia Kameli’s work we find her relation to the book, which is expounded in Stream of stories throughout an exploration encompassing words and imagery, videos, and illustration, and is carried on in the second installation of Elle a allumé le vif du passé. Starting with the title, Le Roman algérien comes across as the writing by the artist of another chapter of Algerian history: that dealing with the “unseen”, to borrow the notion adopted by that philosopher of images, Marie-José Mondzain, with whom Katia Kameli has worked in two of the installation’s films. The unseen, “that which is awaiting meaning in the debate over community”, is conceived throughout the three films based on an initial plunge into the life of Algiers and one of its main thoroughfares: Rue Larbi Ben M’Hibi, through the documentation of a nomadic kiosk that has been there for years. Le Roman algérien, chapitre 1 gravitates around this kiosk selling images whose owners, Farouk Azzoyug and his son, daily set up and display a new composition made up of old postcards and reproductions. These archives, which here, too, overlap original and copy, sketch an alternative history in a country where the image is hidden, and at times confiscated: this image factory re-composing a Warburg-like atlas, traces of a colonial past and documents about what has been, is exposed to the eyes of passers-by, young people, and intellectuals, in order to re-create the differing representations of memories of Algiers. This work on the shared image also gives priority to the development of a history as seen by women, a “herstory”, where the artist collects the words of militants, journalists, artists and philosophers. Marie-José Mondzain’s participation in chapters 2 and 3 is incidentally emblematic of this: first and foremost in the analysis of the rushes of chapter 1 and in the rekindling of archives and history through work involving looking at the images, then in the actual participation of the intellectual woman, who straightforwardly penetrates the space of the image and is no longer content to comment on the facts in order to bear witness. In this sense, like something haphazard that becomes organized, the images of the Hirak appear like a history in the process of being made, and which intermingles with, it just so happens, the absence of images of the dark decade which the photo-journalist Louiza Ammi comments on.

Exploring facts, inviting outside eyes, and sharing words to give a complex vision of culture and history represent Katia Kameli’s artistic and critical approach. This generous work will finally be taken up in Marseille in October 2021, as part of the exhibition “EUROPA, Oxalá” at the Mucem. This time around it is from the curating angle that the artist, together with Antonio Pinto Ribeiro and Aimé Mpane Enkobo, will question the colonial legacy, by broaching memorial and postcolonial studies, and bringing together various European artists whose parents and grandparents hail from former colonies.

- Walter Benjamin in his lecture “The Author as producer”, “Speech given at the Institute for the Study of Fascism in Paris, 27 April 1934”, in Letters to Brecht, pp, 147-164.

Image on top : Katia Kameli, « Elle a allumé le vif du passé », 2020. Vue du plateau 1 du Frac / View of the Frac’s stage 1, Le Roman Algérien, 2020. © Katia Kameli, ADAGP, Paris, 2020. Photo : Laurent Lecat / Frac Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur

Related articles

Performa Biennial, NYC

by Caroline Ferreira

Camille Llobet

by Guillaume Lasserre

Thomias Radin

by Caroline Ferreira