Derek Jarman

« Dead Souls Whisper (1986 – 1993) »

CREDAC

25.09.21-19.12.21

“Paradise haunts gardens and it haunts mine,” Derek Jarman wrote in his notebook.[1] His garden was truly unique: a huge expanse of pebbles by the sea, opposite the Dungeness nuclear power plant on the Kent coast in the south of England. Not exactly paradise. The artist purchased Prospect Cottage– a humble fisherman’s house– in 1986 when he tested HIV positive and lived there until his death at the age of 52 in 1994. A leading figure of the English Underground scene, Jarman did not consider himself a filmmaker, but rather a painter who made films.[2] His cinematographic legacy, however, is carried by the actress Tilda Swinton, to whom he offered her first film role and who was his favorite actress. This is manifested in the work of the director and visual artist Isaac Julien and the director Sally Potter. Artist, filmmaker, and gay rights activist, Derek Jarman, refused any hierarchy between the arts developing a work at the crossroads of the arts, activism and politics, inseparable from his private life.

Born on January 31, 1942 in Northwood, Middlesex, he began painting at boarding school. Following the advice of his father, he first studied history at the prestigious King’s College from 1960 to 1962, then enrolled in the Slade School of Fine Art (1963-1967). “In school, I won all the painting prizes and in Northwood, I was the young prodigy,” he said. “When I got to the Slade School of Fine Art, I suddenly realized that I wasn’t as good a painter as I thought I was.”[3] For Jarman, painting was a way to escape. His early paintings are portraits and abstract compositions that reflect the influences of the London School, pop and conceptual art. The quiet beauty of the geometric landscapes of Avebury Henge (1973) contrasts with the rich textures and warm colors of A journey to Avebury (1971), one of his first short films shot on Super 8, a romantic landscape film in which his pictorial eye is evident in almost every shot. After his studies, he worked as a set designer for several operas at the Royal Ballet. In 1970, he was invited to create the décor for the film The Devils by Ken Russell. Inspired by the demons of Loudun, the film addresses religious intolerance and preconceived ideas of sexuality. This was a turning point for Jarman, which led him away from painting and towards cinema. The film also proved to be very influential on his own work.[4]

Photo : Marc Dommage / Le Crédac

With little interest in scripted narratives, Derek Jarman favored a pictorial, organic approach, with editing that exalted visual plasticity. He made his first film in Sardinia in 1976 with a very modest budget. Entirely narrated in Latin, Sebastiane is a homoerotic and somewhat candid version of the life and martyrdom of Saint Sebastian. The following year, Jubilee portrayed the English punk scene. In 1979, The Tempest, an unconventional adaptation of Shakespeare’s play, stirred up controversy and established his work definitively in the field of counter-culture. His most revered film is undoubtedly Caravaggio, a fictionalized biography of Caravaggio, painter of the night and inventor of chiaroscuro at the dawn of the 17th century, and marked beginnings of Tilda Swinton’s acting career, who went on to become his muse.

During the seventies, between the shooting of his feature films and his work as a set designer, he made several Super 8 films with his friends that were not intended to be shown. The low resolution, the visible grain and the scratches on the film, often considered as deficiencies, were nevertheless for him a way to obtain a certain texture of painting through film. “The pleasure of Super-8 is the pleasure of seeing language pass through the magic lantern,” Derek Jarman wrote.[5] Sloane Square–, shot in 1974 and titled after the street of the apartment that the artist rented from a friend of his– showed the everyday life and a costume party organized for his departure after receiving an eviction notice. The soundtrack is by Simon Fisher Turner, who will sign almost twenty years later that of Blue. In addition to his films, in the 1980s he directed several music videos for the British music scene, working with The Smiths, Bryan Ferry, the Sex Pistols, Marianne Faithfull, Suede and the Pet Shop Boys. In these short films, we find some of the familiar motifs of Jarman’s universe, from the masks and mirrors of Marianne Faithfull’s “Broken English” video (1979), to the use of Super 8 film in fast motion for The Smith.

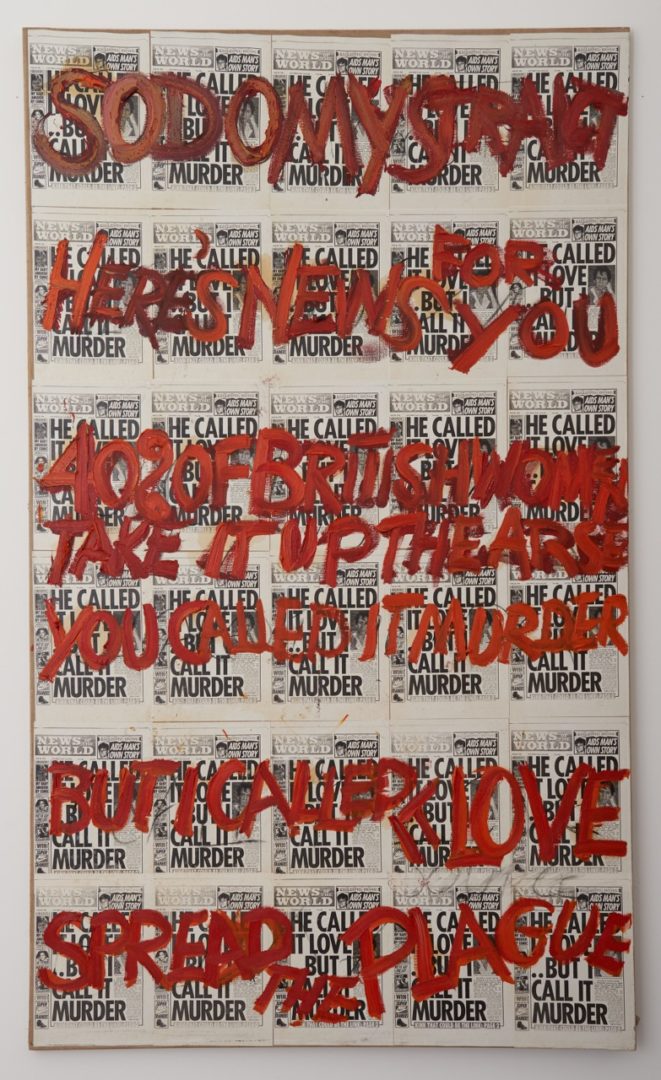

In 1986, Derek Jarman discovered he was HIV positive. He thus decided to leave London for Dungeness where he created the garden that took on a truly important place at the end of his life and where he returned to painting. As the first public figure to reveal his status at a time when the sick were vilified and considered as pestiferous, he became one of the main voices in the fight against AIDS, developing an activist art, an art of urgency in which visual creation and activism came together. “I have no words, my shaking hands cannot express my fury. All I have is my sadness,” says the narrator of The Garden directed by Jarman in 1990. This bitter anger is his own. The small paintings made in Dungeness (1989-91) are executed with tar. The black tarred background is itself a metaphor for the dark areas where the enemies stand. These black paintings with objects take on the form of ex-votos or vanities, establishing a mise en abime of human precariousness. “If you consider black as the negative, it is very, very important. That’s what Pasolini did: show people the negative… There are too many pretty images. It is not at all like in real life,” he stated.[6] In a kind of syncretism, a series of busts represents domestic gods. Jarman also invented a queer genealogical lineage from Shakespeare to Rimbaud via Caravaggio. In 1992, he was invited by his gallerist Richard Salmon to exhibit at the Manchester City Art Galleries (now Manchester Art Gallery). In just a few weeks he produced the Slogan Paintings series, also known as Queer Paintings after the title of the exhibition, some of which are the largest he has ever painted.[7] They were presented back to back. Each one consists of a grid of tabloids violently covered with thick impasto paint. On some of them, one can read the words “AIDS,” “BLOOD” or “PLAGUE.” The artist chose words and abstract colors rather than images to translate his experience of AIDS. Between language and abstraction, he subverted the way the media and government treated HIV positive people. If the body is failing it, is also because of inaction and homophobia. With this series, he used art as a public protest.

Courtesy : Keith Collins Will Trust et Amanda Wilkinson, Londres

Derek Jarman directed his last film Blue in 1993 when an infection temporarily blinded him. The film is devoid of images because they “hinder the imagination, require a narrative and suffocate with an arbitrary charm, the admirable austerity of the void,” according to its author. For one hour and fifteen minutes, viewers face a screen with the invariable color IKB, accompanied by an original soundtrack composed by Simon Fisher Turner. The film tells the story of the bodily transformations experienced as a result of contact with the AIDS virus, and invites the viewer to a somatic experience, a meditation on color and emptiness based on the perception of sounds and words extracted from poems and the artist’s hospital diaries read by actors Nigel Terry, John Quentin and Tilda Swinton.

A filmmaker by accident, a painter by necessity, Derek Jarman built a body of work that drew on philosophy and literature as much as on his personal life to critically question the world around him. “For him, creation was therapy and a metaphor of his own survival,” wrote Claire Le Restif. At once a painter and poet, director and writer, gardener and activist, Jarman has played a leading role in the global reclamation of the term queer, offering a possible alternative to rigid labels and categories of sexual and gender identities. The mirror is a recurring motif in his work. The question of reflections, of who is looking, functions as an allegory of society’s pretense. He imagined his garden and managed to make it grow and bloom in an arid region, but the debris transformed into relics contained in his tarred black paintings will remain powerless– a miracle was not born from the mud. Derek Jarman died on February 19, 1994 at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London. His work, with its abundant aesthetics, between darkness and grace, is like an immense self-portrait, a marker of his time, a history of humanity.

[1] Derek Jarman, Un dernier jardin, Thames & Hudson, 1996.

[2] Nicole Cloarec, « Derek Jarman : le peintre à la caméra », Itinéraires [online] 2014-2 | 2015, published 16 June 2015, accessed on 02 October 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/itineraires/ 2414

[3] Mark Rydel, Derek Jarman – A portrait, 1990, conversation in « Derek Jarman », Please to meet you, n° 11, September 2021, pp. 8-9.

[4] See Rowland Wymer, “Derek Jarman’s Renaissance and The Devils (1971).” Shakespeare Bulletin, vol. 32 no. 3, 2014, p. 337-357.

[5] Derek Jarman, Dancing ledge, Quarter Books Ltd, 1984, p. 129.

[6] Mark Rydel, op. cit.

[7] Derek Jarman Queer, Manchester City Galleries, 16 May – 28 June 1992.

. . .

Head image : Dereck Jarman – Dead Souls Whisper (1986-1993) Photo : Marc Domage / Le Crédac

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Camille Llobet, After the End. Maps for Another Future, Wolfgang Tillmans, Bergen Assembly, Aline Bouvy,

Related articles

Performa Biennial, NYC

by Caroline Ferreira

Camille Llobet

by Guillaume Lasserre

Thomias Radin

by Caroline Ferreira