Die Welt als Labyrinth

Mamco, Genève, 28.02-06.05.2018

“An exhibition on the Situationist International, as a rule, means a lot of tracts and a lot of lousy paintings”. This is one of the pitfalls which Paul Bernard, the general curator of “Die Welt als Labyrinth” at the Mamco in Geneva, was keen to dodge. But it is not the only pitfall. Because the exhibition grants plenty of room to Lettrism, the International Movement for an Imaginist Bauhaus, the Alba Experimental Laboratory, the London Psychogeographical Committee, and the like, the figure of Guy Debord is not pivotal and Paris is not the capital of this constellation. This, incidentally, is what is indicated by its German title, which borrows the name of a Situationist International event. This latter should have taken place at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1960, had its members not refused any kind of compromise with the institution, which caused the show to be cancelled. A plan on view in the first room of the exhibition in Geneva reveals what this “World as a Labyrinth” might have been. Its entrance was to be created by the first visitor, and the exhibition was to have included an “annoying zone”, a “rain zone”, a diffusion of fog, a “Jack the Ripper street” and many other areas, most of which, somewhat surprisingly, conjure up contemporary practices. At the same time, drifts were to be held in the city of Amsterdam.

Gil Joseph Wolman, Écriture gestuelle sur fond bleu, 1962. Écriture et huile sur toile. Coll. part., courtesy Lionel Spiess, galerie Spiess Seconde Modernité, Paris.

The sheer negativeness with which the SI is often summed up thus appears simplistic. This is just one of the aspects of a bustling proliferation which is well described by the show. This profusion is picked up by the spectator merely by taking a close look at the small handful of Gil Joseph Wolman’s works that are on view. Among these latter there are Lettrist paintings (such as this Ecriture gestuelle of 1962 which stands out against a sumptuous blue cloud-like backdrop) and others (an almost white monochrome cut into irregular rectangles in which strange empty phylacteries appear). Some ten years earlier, the same Wolman produced L’Anti-concept (in 1951 or thereabouts), an anti-cinematographic “film”, with no apparent screenplay, projected onto a weather balloon and accompanied by a voiceover which, notably, includes the Mégapneumes, a Wolman brainchild (“poems made of expectoration”, we are told by the press release). The whole is accompanied by rare flashing effects announcing the flicker film, whose goal is to shatter the illusion of continuous movement caused by the 24 frames per second.

If the failure of the exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum is the consequence of a radical criticism of the museum as institution, the creation of the International Movement for an Imaginist Bauhaus (MIBI) and then that of the Alba Experimental Laboratory indicates a total rejection of the modernist school of art. The first resulted from Asger Jorn’s refusal to work with Max Bill on the creation of a “new Bauhaus”, i.e, the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm. As a reaction, Jorn launched the MIBI with Enrico Baj, which resulted, in 1954, in the organization of an “International Ceramics Meeting” in the small Italian town of Albisola, in which, in addition to the above-mentioned artists, such figures as Karel Appel, Roberto Matta and Sergio Dangelo, to name just them, took part. In the manufactory where they officiated, the person in charge of production first noted that many of them knew nothing whatsoever about ceramics, and duly handed out school notebooks to the participants, urging them to draw before they started to model. It is not insignificant that those who rejected Bill’s new Bauhaus, and were driven by revolutionary aims, covered the said notebooks (on view in the exhibition) with their drawings. Two years later, Jorn met Giuseppe Pinot-Gallizio, a fifty-something at the start of an artistic career (as we shall see), and the philosophy student Piero Simondo, whose 1956 picture Sans titre was a sort of shaped canvas that was both sublime and ridiculous.

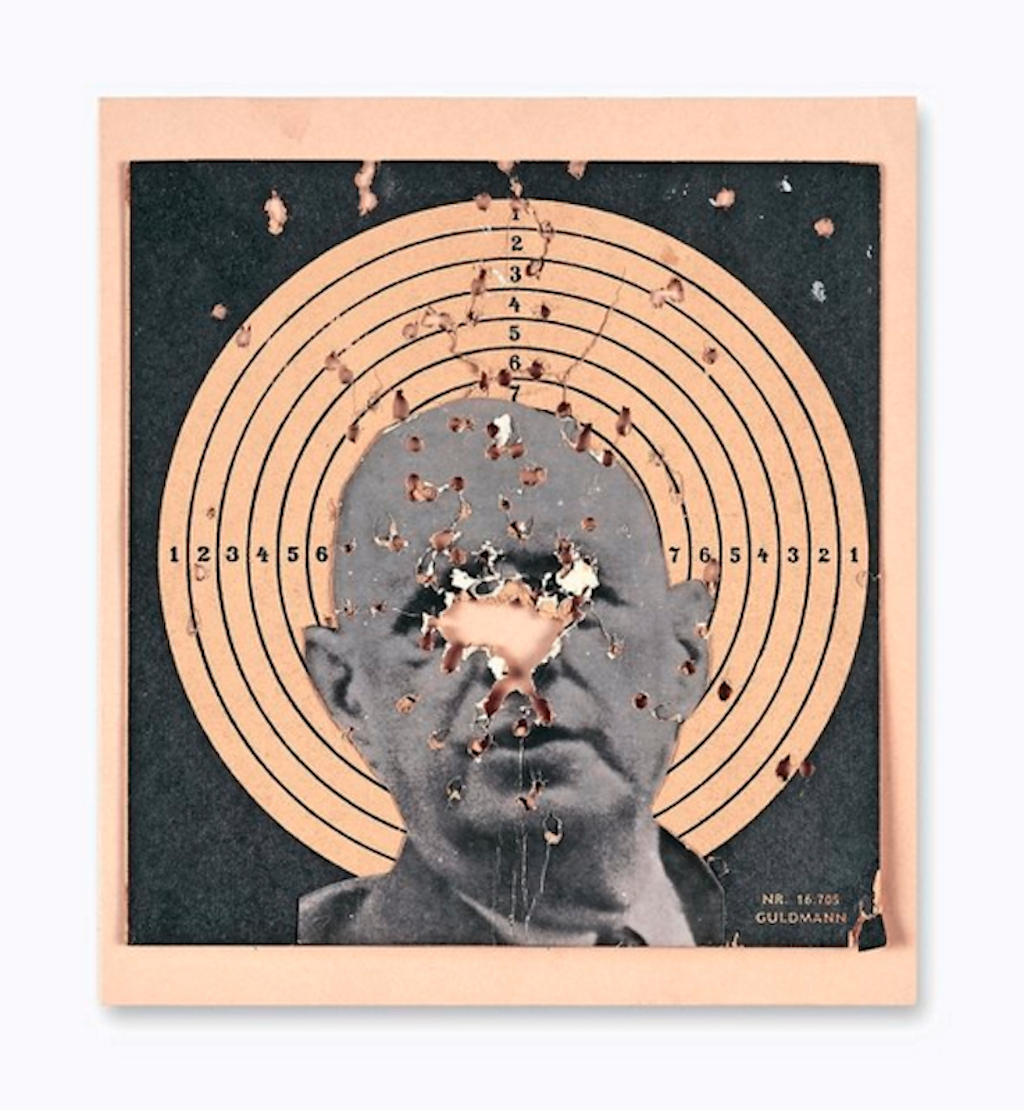

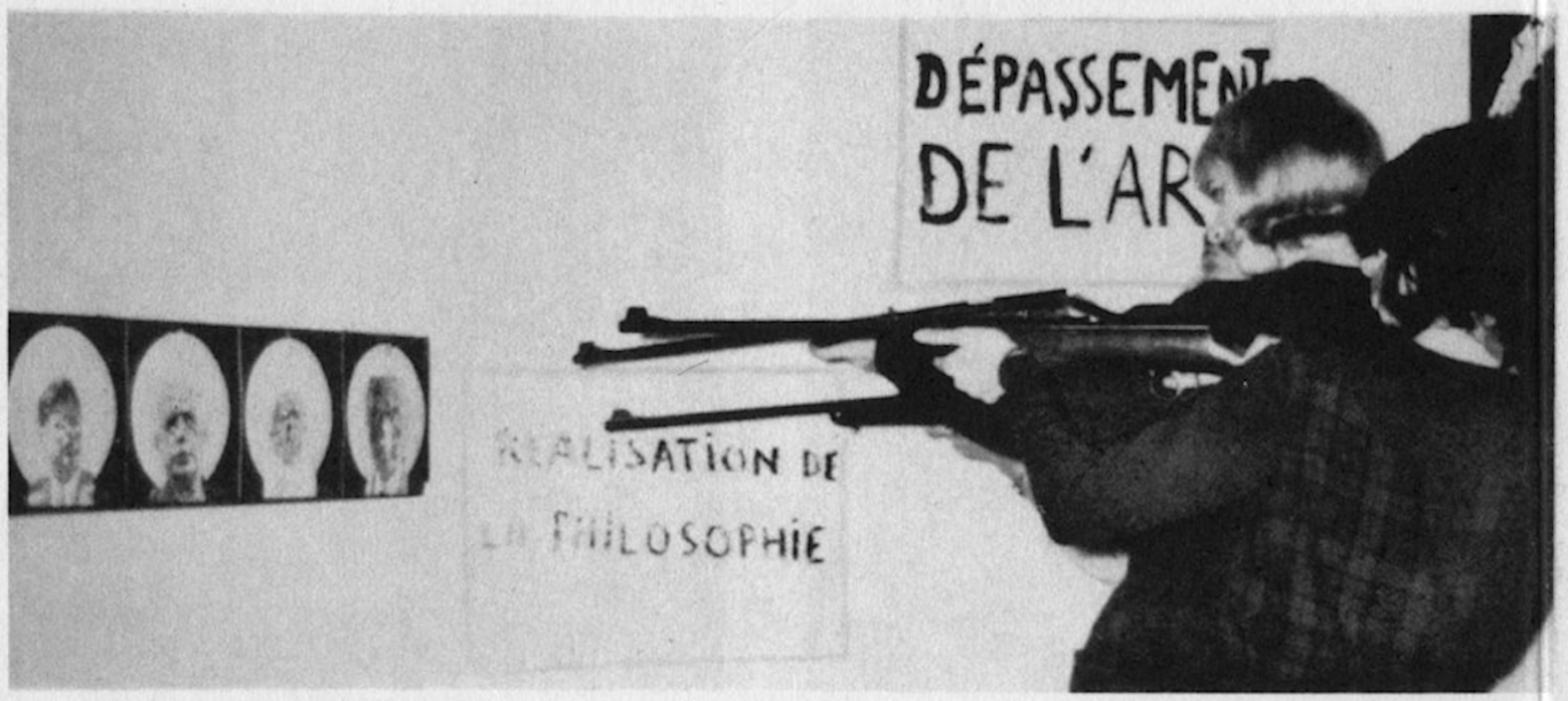

Less ridiculous, the only exhibition ever presented by the SI was held in 1963 at the EXI gallery in Odense, Denmark. The argument used by J.V. Martin, Guy Debord and Michèle Bernstein was the revelation, by the Spies for Peace collective, of the construction of atomic bomb shelters reserved for members of the British government. “Die Welt als Labyrinth” partly re-creates the atmosphere of that exhibition with its name that is at once coded and full of verve (“Destruction of the RSG-6”), in which the public was invited to fire rifles at the effigies of various pro-nuclear statesmen (De Gaulle, Kennedy, Franco, Khrushchev and Adenauer), and where Debord showed the four paintings that he had produced (with the instructions Dépassement de l’art, Réalisation de la philosophie, Tous contre le spectacle and Abolition du travail aliéné in black on a white ground).

In the largest exhibition room at the Mamco, the works of Pinot-Gallizio and Jorn refer, if you will, to a Debord proposal whereby “the suppression and making of art are the inseparable aspects of one and the same surpassment of art”.1 On the suppression side was Pinot-Gallizio with his “industrial” paintings, a mixture of oil paint and resin applied on rolls of canvas measuring up to 70 metres in length, before being sold by the yard, it just so happened. Where surpassment is concerned, Pinot-Gallizio stood out again with his Caverne de l’anti-matière (1959), an environment wallpapered with the said painting, seen by its maker as an “accelerator of olfactory and acoustic chromatic emotions”. But is it probably in Jorn’s Modifications (1959), pictures purchased in bric-à-brac shops before being partly repainted, that we find both the suppression and production of art. But there is no apparent surpassment to be indicated in these pieces. This would lend plausibility to the hypothesis whereby, for Jorn, the avant-garde remained revolutionary and was not to be resolved in philosophy—the avant-garde does not surrender, reads the grotesque title of a 1962 “disfigurement” (défiguration).

1 Guy Debord, La Société du spectacle, Paris, Gallimard, 1992, p. 185.

(Image on top: « Destruction of RSG-6 », Galerie Exi, Odense, 1963.)

Related articles

Performa Biennial, NYC

by Caroline Ferreira

Camille Llobet

by Guillaume Lasserre

Thomias Radin

by Caroline Ferreira