Hilma af Klint

Hilma af Klint

Guggenheim Museum Bilbao

October 18, 2024 – February 2, 2025

The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao is presenting a retrospective of Hilma af Klint from 18 October 2024 to 2 February 2025. Ever since her works were brought to public attention in the 1980s, the Swedish artist has been the subject of extreme attention, not to say a veritable cult, since her death in 1944. What accounts for this fervour? Certainly her artistic and sensitive itinerary has something to do with it, the native of Stockholm having demanded that her works not be divulged or exhibited for ten years after her death; this contributes to the establishment of a legend that has continued to grow with her successive rediscoveries and consecrations. But that would be to reduce the scope of his work to this anecdotal aspect, to say the least. Most of her admirers acknowledge that she played a major role in the invention of abstract art, on a par with her male contemporaries who, in their time, enjoyed international recognition, whereas af Klint reserved her discoveries for the chosen few who had access to her paintings. The other aspect of his work, which helped to make af Klint a universally acclaimed figure, is certainly the content of his paintings, which make explicit reference to his attachment to a spiritualism borrowing from various currents, including Rosicrucianism, theosophy and anthroposophy. However, we should not overlook the extreme formal inventiveness of an artist who was able to produce forms and formats that were resolutely disruptive for their time.

Af Klint began her career in a fairly classical manner, after attending the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts, where she learned to paint according to the prevailing canons. She began to produce figurative paintings, such as the one on display in the first room of the museum, which shows undeniable virtuosity and was inspired by French painters such as Corot (Summer Landscape, 1888). Her first forays into abstraction met with little success, and she decided to show them only to a small circle of friends who shared her scientific and spiritual visions. In 1906, she embarked on her greatest work, a series of large-format paintings intended to cover the walls of the temple dedicated to theosophical thought: Paintings for the Temple.

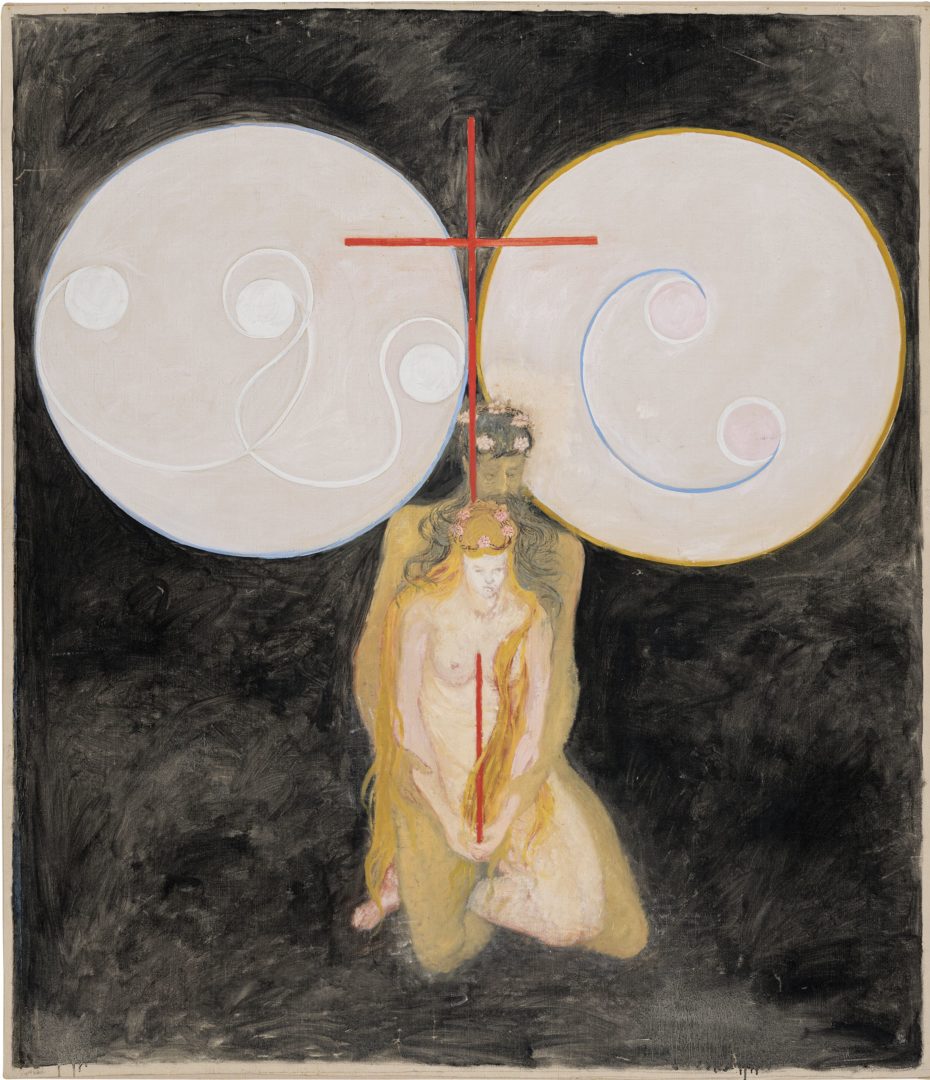

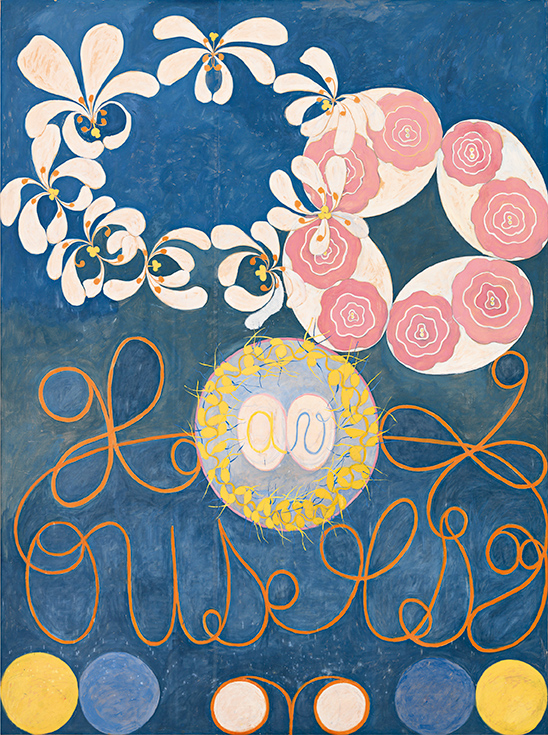

Starting from a fusion of figuration and abstraction, in her early experiments with non-representational art, over time the artist almost entirely discarded the figurative dimension, focusing solely on abstract productions. In particular, she favoured a geometric abstraction that encompassed the entire canvas, unlike Kandinsky, who at the same time was deploying geometric motifs in expressionist compositions based on the intensity of colour, whereas the Swedish artist used a resolutely more subdued palette. Like the Russian painter, however, af Klint tried to share her spiritual values, which, as she would find out to her cost, were not about to be accepted by a Swedish public still faithful to representation1.

Klint’s painting strongly reflected the intellectual and scientific influences that permeated society at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries, in particular Darwin’s theories on evolution, which continue to provoke much debate half a century after their publication, but also more esoteric thoughts such as Rosicrucianism, Anthroposophy, for which she decided to produce a series of large paintings to cover the walls of a temple dedicated to this discipline, the famous Paintings for the Temple, ‘the ambitious cycle that was to characterise her’, in the words of Tracey Bashkoff2, chief curator of the Guggenheim in New York. A temple that was never built. Throughout her life, however, she maintained a fairly close relationship with Rudolf Steiner, the founder of anthroposophy, although her encounter with Steiner left a mixed impression, due to his lack of enthusiasm for productions that he felt were too mediumistic in nature and not sufficiently oriented towards introspection. This reaction on the part of a respected outsider may have led her to restrict her presentations to her inner circle.

The exhibition at the Guggenheim traces an artistic itinerary intimately linked to the evolution of her spiritual influences, which were to assert themselves throughout her life. Organised chronologically, it presents the artist’s very academic beginnings, his influence on French Impressionist painting and, in the same room that opens the visit, shows ‘fusional’ paintings marked by the figure of the swan, an alchemical symbol but also of the ‘greatness of the spirit’, according to the founder of modern theosophy Helena Blavatsky. Af Klint’s spirituality began at the dawn of her career, marked by the spiritualist experiences she had as part of The Five, a group of women artists who had met at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts. The Five shared a vision of art designed to improve the lot of a humanity dislocated by initial chaos. The five young artists received messages during trance sessions, which were then transcribed into notebooks in the form of automatic drawings. It is clear that this decisive period in the young artist’s intellectual and emotional development, laden with mysticism and strongly tinged with the occult, was to mark the whole of her future artistic creation. Paintings for the Future clearly shows the stages in the development of a painting, giving broad access to all of af Klint’s major cycles, from Primordial Chaos Canvases to The Eros Series and The Large Figure Paintings, via her famous notebooks and ending with the dazzling series The Ten Largest, which only a few museums are able to stage: A scientifically accurate exhibition that allows us to reconsider the position of a woman artist who, despite being far removed from the main centres of artistic and intellectual life in the nascent 20th century, succeeded in imposing the revolutionary idea of pictorial abstraction against all the representational conventions in force in her native Sweden.

1 Andrea Kollnitz “Like Kandisnky, af Klint wanted her work to communicate spiritual values, even messages, and also like him, she didn’t expect her contemporary audience to understand this new approach to artistic expression.” Catalogue de l’exposition Paintings for the Future, p75. Museum Guggenheim Publications New York.

2 Tracey Bashkoff, « Temple for the Paintings », op. cit., p. 17.

Head image : Vue d’exposition Hilma af Klint, Musée Guggenheim Bilbao, 18.10.2024 — 02.02.2025.

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Playground, Lyon Biennial, Anozero' 24, Coimbra Biennal, Signs and Objects. Pop art from the Guggenheim Collection at Guggenheim Museum, Momentum 12 at Moss,

Related articles

Ralph Lemon

by Caroline Ferreira

Ho Tzu Nyen

by Gabriela Anco

Plaza Foundation

by Andrea Rodriguez