Interview Anne Bonnin

Anne Bonnin has just opened two major exhibitions—one at the Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine, La MÉCA, “Les Péninsules démarrées” (Untied Peninsulas), followed by another at the Grand Café, Saint-Nazaire, with the Portuguese artist Mattias Dennis. She is currently preparing another large-scale exhibition at the Grand Café, “Souvenir nouveau” (New Memory). The titles as well as the artists selected for the exhibitions are equally as surprising as they are unexpected in today’s contemporary art scene where the overarching themes of the day are favoured. The curator’s statements do not, however, in any way overlook today’s major issues. If there were a message to deliver, it is precisely that exhibitions do not contain any particular message, but rather exist to promote the intensity and singularity of the artworks, transcending their supposed obsolescence, through a dissonance and atemporality which allow them to avoid trends and age favoritism.

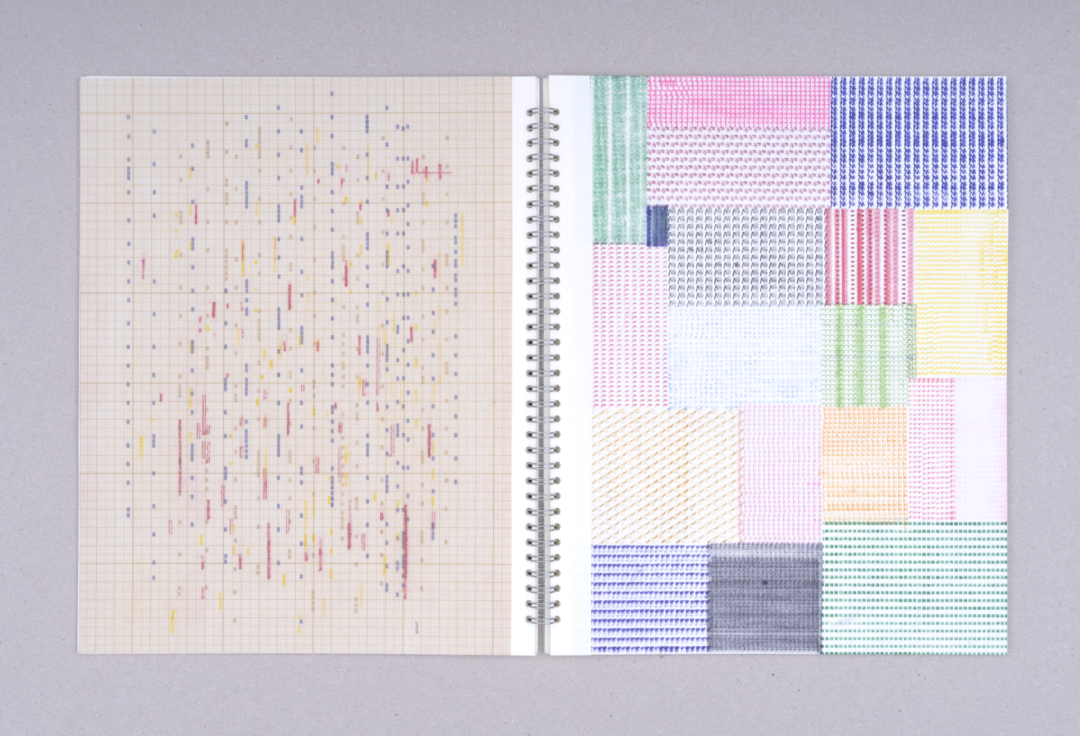

(De gauche à droite) Avec les œuvres de Nina Childress (Courtesy de l’artiste et Art : Concept, Paris © ADAGP, Paris, 2023), Ethan Assouline et Jean-Pierre Allain (© ADAGP, Paris, 2023)

02 “Les Péninsules démarrées”, Mattia Denisse, “Souvenir nouveau”. In the year following the relative lull due to Covid, with the resulting slow-down of the public health crisis, it would seem as if the career path of the curator is one which follows an accordion-like pattern, with periods of down time punctuated by sudden accelerations. How has it been for you professionally, and how are you dealing with these changes of pace?

Those changes of pace always become enmeshed, being that assignments or invitations determine these cycles, and research topics are what give rise to the invitations. Each project has its own temporality, generates its own method. For example, “my” Portuguese exhibitions (2022), which each had their own catalogue, required long periods of both historic and contemporary research, conducted on-site. I worked on those for something like three years straight. Their conception and format were adapted to the content and museographical in nature, with many loans from Portuguese museums. The art centre exhibitions are more straightforward: the two exhibitions I curated at the Grand Café were prepared over a far shorter period of time; the first one, a solo show, was a direct result of the different encounters I had in Portugal, while the second, a group show, “Souvenir nouveau”, which just opened, aims to be a subtle record of the present. The next project (April 2024) uses an entirely different approach. The Zlotowski and Catherine Issert galleries invited me to create a double exhibition and catalogue around Pierrette Bloch and the theme of the stain, which was a classic modern art theme in the period following the Second World War. And, by the way, it was due to the concomitance of this project and the “Souvenir nouveau” exhibition that I got the idea to show Pierrette Bloch’s works in a heterogeneous context, except for one artist -Raffaella della Olga; this idea surprised and then convinced me. To provoke and work with temporal discordance is stimulating. Offbeat, or off-tempo encounters between the works, without creating a spectacle, open up new, unexpected possibilities which allow us to see current events from another perspective, outside the norm. This discord is also in line with a current renewal of our perception of time and of history, which is partially due to the dismantling of our notion of modernity. Art is obviously an ideal space to experiment with things which are offbeat, this can take on subtle forms, such as for example in Bloch’s work—her sober monochromes knitted out of fishing line are contradictory as they evade the dictates of the all-black monochrome. Her repetitive and dirty drawings of circles give a keen sense of time moving forwards while also moving backwards, forming stains which resist the line and are also a precondition of it. The idea of cyclical time, which is non-linear, is prevalent in art, of course, but also in our current political and social climate, which is fairly disastrous.

Vue de l’exposition Hápax au Grand Café, 2023. Photographie Marc Domage.

02 How do you explain this particular notion of curating, out-of-synch with the dominant practise of the exhibition, which is focussed on contemporary, emergent and/or thematic situations?

Actually, I’ve always practised this type of temporal gymnastics and had the urge to think of current artistic practise in offbeat terms. I think this is perhaps because I am, or was, out of synch with my generation (Claude Closky, Dominique Gonzalez-Foester, Pierre Huyghe, Philippe Parreno, etc.) because I got a late start, in 2000—although since childhood art has always been one of my passions, I was lucky in that my mother began taking my sister and I from Niort where I grew up to Paris and Bordeaux from the age of four. I have always had the impression of living out-of-synch from the present. What I love about, what we love about contemporary art, is an intensification of the present, which is sometimes tiring and anxiety-inducing, but this artistic present also invents itself and is created collectively. It is supported and sustained by a dialogue between living artists from all generations.

I like to create spontaneous, “off the cuff” exhibitions, when artists show up with their works—which is what young artists do, by the way—it is lightweight, like the first conceptual artists. The staggering costs of transport, insurance fees, security regulations all put the brakes on the inspiration and spontaneity of the moment, the kairos, which is of course important in contemporary art. At a time when there is an impression of needing to pare things back, in a political, social and ecological time of urgency—in the context of what is happening in the majority of the domains of our political, social and ecological lives—the commodification of art is following an opposing curve. The market is of course, only one aspect of art; it has become, or has once again become, dominant, powerful, violent. It has won many over—institutions are in need of funds. This paring down is in tune with the nomadic conditions of freelance curators who, lacking a permanent exhibition space, wait too long to mount an exhibition, to concretise an idea. The nomadic lifestyle, which is financially unstable, means having to navigate things as they pop onto one’s radar, which means being willing to leave oneself at the mercy of unpredictable weather conditions, sometimes choppy waters, without ever letting go of the stern, to the point where one can run the risk of sinking; it is menacing and dizzying. It is a question of temperament—not everyone likes this feeling. Personally, I do.

02 “Les Péninsules démarrées” (Untied Peninsulas), which was at the Frac MÉCA in Bordeaux last fall and whose title quotes a Rimbaud poem, Le Bateau ivre (The Drunken Boat) was a retrospective exhibition of 135 works. Did you have any prior knowledge of the scene? How did you manage to gather so many artists from a foreign country? I would imagine you must have made a certain number of trips to Portugal in order to hunt down emerging artists, as well as more established ones. How did you approach the selection process?

My interest in Portuguese artists has many sources, with the art itself being the driving force behind it, and the discovery of the artists (Lourdes Castro, Álvaro Lapa, Ana Hatherly, Salette Tavares, Ana Jotta, João Alves, PO.EX…), instead of the country itself, beautiful and pleasant though it may be. My interest came about in an organic way, through conversations with artists I’ve known for over ten years and with whom I spend time whenever I am in Portugal: Pedro Barateiro, Isabel Carvalho, Armanda Duarte, Carla Filipe, Jorge Queiroz, Ana Jotta, Thierry Simões, Francisco Tropa, and others. Ricardo Nicoleau, curator at the Serralves museum introduced me to Portugal while I was conducting research for the Rennes Biennale (2012). Our discussions led me to discover the history, the artists, the artistic and social genealogies. Meeting Lourdes Castro (1930-2022) was a determining factor; she was at the origin of my Lusitanian adventure. Her work, which is equally fascinating and streamlined, as well as her life, were a part of the 1970s. She had such a lightweight and simple way about her—in her work and in her lifestyle as well, which was reflected in her Shadows and her books. She personifies—as did many artists in the 1960s, 70s and even 80s, as well as Ana Jotta, Esther Ferrer, who I hope to work with sometime in the future—is the personification of a formal simplicity in life as in art. So I put together the first Lourdes Castro restrospective in France (2019, Mrac Sérignan), keeping in mind that she made the majority of her work in Paris, where she lived from 1958 to 1983. As I listened to this storyteller, an entire panorama of the European avant-garde emerged, from Vieira da Silva and Árpád Szenes to Tropa, with whom she worked at the São Paulo Biennale organised by curator João Fernandes. This prolifically social woman introduced me to an extensive international network of friends and artistic relationships which spanned over 70 years. She weaved a living history out of stories and anecdotes which progressively took on the form of a project, in various forms. Then, Claire Jacquet asked me to put together an exhibition. I began with the present and went back in time, and then I extended the trip even further—there was another exhibition on Portuguese modernisms at the Maison Caillebotte.

I was also keen to project an image of the international geography of Portuguese art under the Salazar dictatorship—whether abroad in Paris or London especially, or in Portugal, like Helena Almeida, Álavro Lapa, Ângelo de Sousa, all of the artists selected for “Les Péninsules démarrées” had their eyes on the avant-gardes. This geography includes the colonial empire and the war. I translated the relationship between Portugal and its colonial history by showing the painters Álvaro Lapa (1939-2006) and Malangatana (1936-2011)—an internationally recognised artist from Mozambique who is practically unheard of in France—side-by-side. A baroque axis emerged, with the experimental poetry group PO.EX (Ana Hatherly, Salette Tavares, E.M. Melo e Castro, among others), which had a truly avant-garde approach and organised performances, appearing in the orbit of the Brazilian poetry group Noigrandes, in 1964. PO.EX created an essential link, a bridge between the Portuguese baroque movement and experimental poetry, by highlighting the experimentation characteristic of the baroque as expressed through word games, enigmas, metamorphoses. PO.EX avoided censorship through the use of humour, breaking with the mythologisation and mystification of the past, via dictatorship.

02 I would imagine that the Mattia Denisse exhibition at the Grand Café also resulted from the discoveries and exploration of the Portuguese scene during the preparation of “Les Péninsules démarrées”?

Mattia Denisse’s solo exhibition at the Grand Café was indeed the result of this exploratory stage in Portugal, leading to the discovery of a French artist who had been in Lisbon for the past twenty-five years, and was practically unknown in France, with the exception of a select few, like François Piron. Mattia Denisse regularly works with the artistic duo João Gusmão and Pedro Paiva (although not since their separation). Inspired by pataphysics, his drawn works, which are an authentic and absurd comedy-cosmogeny, contributed to the wider exposure of a body of French literature in Portugal. This drawing exhibition was a first for the Grand Café with regard to their usual curatorial line which tends to favour contextual projects, and three-dimensional forms.

02 This solo exhibition will be followed by another, collective exhibition at the Grand Café in Saint-Nazaire; how is it possible to go from the singular to the multiple? Also could you tell us about the strange title?

For this second project at the Grand Café, I expressly created a group show which would have no theme, as an expression of disparity. The title, “Souvenir nouveau” (New Memory) is an example of a temporal oxymoron which reveals the friction between two different temporalities, as opposed to the avant-gardist shock which implies a break with the past. The tension between two opposite moments is highlighted by the title, with its outmoded charm, juxtaposing past, present and future. Time moves forward while going backward, becoming shrub-like, such as with Pierrette Bloch’s looped lines, or her knitted monochromes. The title creates a dissonance, but it is nuanced due to the memory which tones down the novelty; there is a double-vision effect.

For the summer group exhibition at Grand Café, I was really trying to situate myself in an immediate present, like a seismograph of the current moment, in which the spectator would play the role of the needle. This palpable immediacy, this lived-in present—there are actually quite a few bodies in “Souvenir nouveau”— differs from the virality of the instantaneous, abolishes the meaning, the very notion of the present. This experience has become ordinary—we spontaneously layer current events and information onto the present. Everyone knows how hard it is to avoid doing this. The title, “Souvenir nouveau” is also unrelated to the avant-garde shock of the new, which was for a long time the predominant model in modern art and which has now been undone and complexified. It brings a temporal texture and solidity to mind—I really would like to treat the present as a memory, to suggest a memory for the present, a depth of field. The absence of a theme allows for ideas to be worked out in an unfiltered way, like intuitions, in order to show them and solicit a memory of the present. This was why I chose different ambiances for each of the three spaces of the Grand Café: one is very pop, with bright colours and bold graphics, with references to pop culture, with counterpoints. The second is mysterious, with Bloch and the Indian artist Amol Patil, while the third plays upon disparities and contrasts to the point where it all just explodes; this space has three suns.

1 « Les Péninsules démarrées », Frac Méca, 16 septembre 2022 – 26 février 2023.

Vue de l’exposition Souvenir nouveau au Grand Café – centre d’art contemporain, Saint-Nazaire, 2023. Photographie Marc Domage.

______________________________________________________________________________

Head image : Vue de l’exposition Souvenir nouveau au Grand Café – centre d’art contemporain, Saint-Nazaire, 2023. Photographie Marc Domage.

(De gauche à droite) Avec les œuvres de Mélanie Matranga (Courtesy de l’artiste et High Art), Liz Magor (CourtesyMarcelle Alix, Paris), Laurent Proux (Collection privée, Courtesy Semiose, Paris @ADAGP, Paris, 2023), Anne Bourse (Courtsey de l’artiste et Crèvecœur, Paris) et Ethan Assouline

- From the issue: 104

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Modern Love at musée d'art contemporain d'Athènes, Chris Sharp,

Related articles

Ho Tzu Nyen

by Gabriela Anco

Hilma af Klint

by Patrice Joly

Plaza Foundation

by Andrea Rodriguez