Isa Genzken, Basic Research Paintings

ICA, Upper Galleries, London, from 30 June to 6 September 2015

Isa Genzken, “Basic Research Paintings”, ICA, London. Photo : Mark Blower.

As is her wont, Isa Genzken will have little to say about this set of paintings brought together on the ICA’s walls by Gregor Muir, director of that august London institution, apart from one striking thing: they have been created to go hand-in-hand with her sculptures, to be hung behind them, to “decorate the rooms with the sculptures”. This, incidentally, explains why they have never yet been shown,1 even though they were produced between 1998 and 1991. Is there any point in mentioning that, at that particular time, Genzken was Gerhard Richter’s wife? It is perhaps amusing now that we are in fact acquainted with the canvases’ primary intent. It is also perhaps altogether anecdotal. Let us leave everyone free to make any comparisons deemed relevant, or otherwise.

Isa Genzken, “Basic Research Paintings”, ICA, London. Photo : Mark Blower.

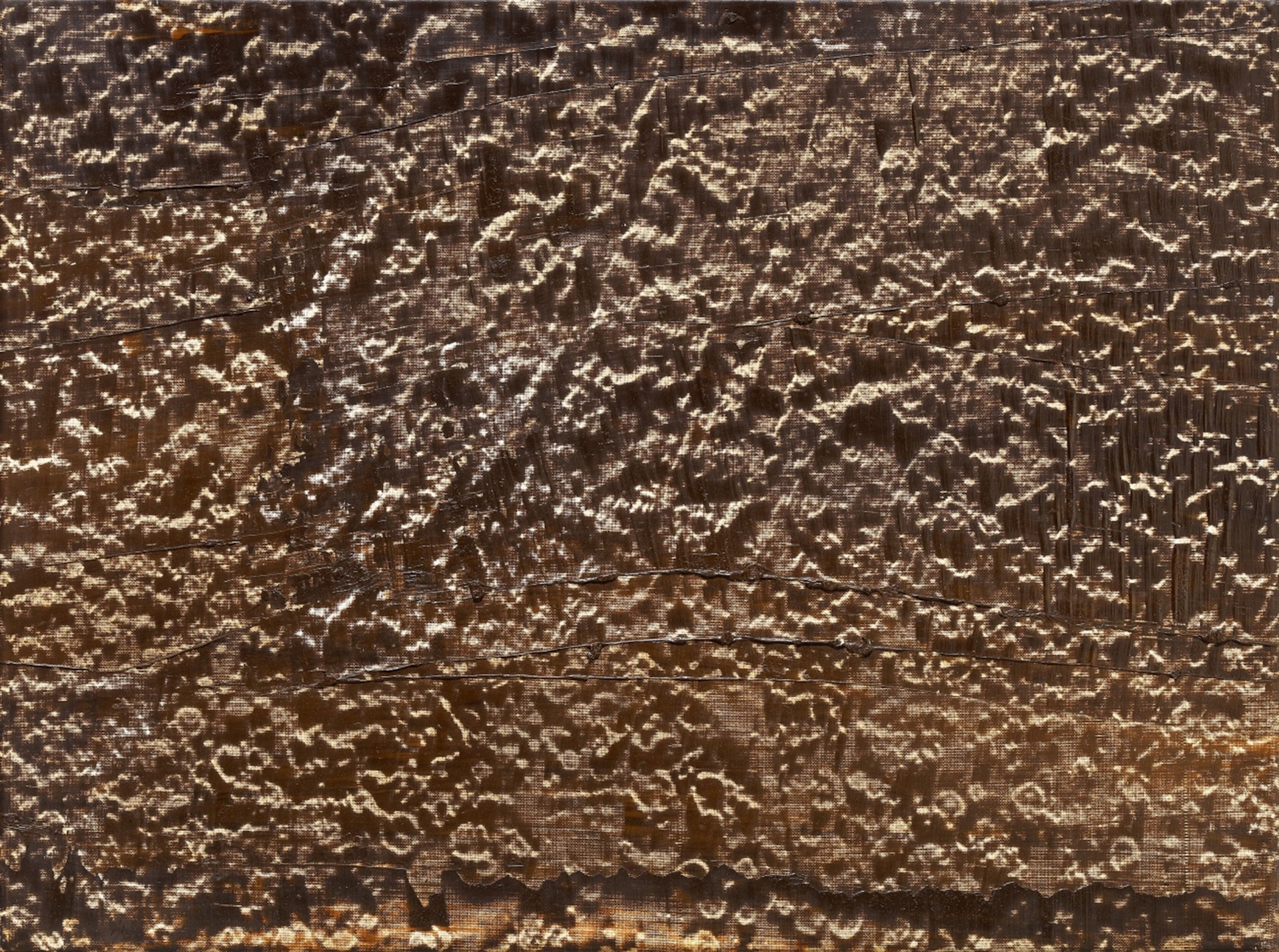

So where this set of paintings is concerned, let us in no uncertain terms express the strength with which they have surprised, disturbed and fascinated us—the list of verbs could be a long one. It is a fact that their “photographic” look is extremely disconcerting, and this is why they were not terribly successful at the very end of the 1980s.2 There is in fact something flagrantly anachronistic about what we think we are unearthing in them: satellite photos steeped in an arresting photo-realism, “images” of stony deserts, barren lands, dry planets with rough surfaces, paddy fields gone to thick forest… So, “images” that sidestepped Google Earth a good decade before the creation of that software. The palette of greens, browns, blacks, dark greys and a little sepia incidentally has something “video-like” about it, above all when, in places, a few dashes of bright colour come to the fore, here an almost dayglo yellow, there a dram of dazzling red. Above all when, at times, the surface seems as if pixellized.

Isa Genzken, “Basic Research Paintings”, ICA, London. Photo : Mark Blower.

If we pull ourselves together and abandon the idea of digital images working their way into the tangible, going beyond the screen and offering us a vision that is not backlit and not mechanized, if we forget this fantasy involving the re-appropriation of visions which man has helped to make possible, but which he has not directly created, if we drop that desire to re-take control of what is produced by the machines which we have produced, which make things that we can’t make without them, if we unravel that temptation to see in them a way of re-physicalizing the digital (an impression bolstered by the painted edges of the canvases tending to objectify these latter, separating them from the glossary of the immateriality of the image on the screen), then what do we see? In a vague way, these reliefs were once depicted in geography books; perhaps views of maquettes of those little landscapes that surround construction projects, with their rough representation of green spaces—but dwelling-less and with no series of offices in sight, still less any human beings, even in the form of plastic figurines; in a confused way, are they natural zones that are still virgin, or already destroyed?

Isa Genzken, Basic Research, 1989, oil on canvas, 90 x 75 cm. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne.

Nonetheless, when we look at them, no anxiety comes forth, almost something more like serenity, to do with what comes about when you look at sand, at once evasively and attentively. It’s as if we were observing the earth’s skin, the depths of the sea, antique ruins. It’s a bit like the whole world processing past us, without us knowing what to focus on, and the intensity of this painting exults in this permanent confusion. Deep in a Pascalian vertigo somewhere between the extremely physical and the extremely digital, between an earth’s crust that we might skim and the failures of the mechanized image, of a photocopy enlarged a hundred times, re-copied, scanned, of an image of the deepest depths of the image’s weft—effects coming between Polke’s dots and Guyton’s glitsches—our eye forever zooms and de-zooms in one and the same motion. Getting closer doesn’t solve anything. To the great frustration of our intellect, everything we see is traces of scraped impastos, slight dazzles, the grain of the canvas. The comforting physicality of paint, in a nutshell. In terms of vertigo, nothing other than a coloured matter that has imbued the canvas. A thoroughly pictorial painting, a relation of the surface to the altogether classical depth: the flatness or quasi-flatness of the coloured expanse, “figuration” of a surface which opens onto faraway potential. Yet there is absolutely no question of figuration. So is a photorealist abstraction involved? An image of infinitesimal precision, but an image that shows nothing?

What we can say, by way of conclusion, about this set of paintings, whose contemplation has plunged us into a far-reaching immersion, is that the “only” thing that it represents, if we may so put it, is the floor of the artist’s studio. This same floor on which, in tandem, she devised the sculptures we are acquainted with, in particular her concrete Fenster works, for which she sought out foils, she covered it with oil, applying her canvases to it and, with great swipes of a squeegee, imprinted its texture.

1 This exhibition was previously shown at the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in Turin from 29 October 2014 to 1 February 2015.

2 Simon Denny, “Out to lunch with Isa Genzken”, interview, Mousse n°22, February 2010. http://moussemagazine.it/articolo.mm?id=508

Isa Genzken, “Basic Research Paintings”, ICA, London. Photo : Mark Blower.

- From the issue: 75

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Andrej Škufca, Automate All The Things!, LIAF 2019, Transnationalisms, Signals,

Related articles

Ho Tzu Nyen

by Gabriela Anco

Hilma af Klint

by Patrice Joly

Plaza Foundation

by Andrea Rodriguez