Lyon Biennial

The 17th Lyon Biennial has just opened its doors. One of the leading contemporary art events in France and Europe, in terms of visitor numbers, the event’s reach, the number of artists invited, and the sheer size of the spaces involved – the gigantic scale of the Grandes Locos, a former locomotive repair factory, could almost make the abandoned former Fagor factory and its 8,000 m2 look like a run space… – is getting ready to welcome the flood of visitors. This year’s curator is Alexia Fabre, who for many years ran the MACVAL in Vitry and recently took over as director of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. The title of the biennial, Les voix des fleuves (Voices from the Rivers), suggested that the event would focus on the identity of ‘natural subjects’, in the spirit of Camille de Toledo and his parlement de la Loire (Parliament of the Loire). But according to the curator’s intentions, this year’s edition refers more to the geography of the city and the proximity of the biennial’s venues to the river, from which emanate the vibrations and songs that are supposed to have a (positive) influence on our moods. One thing is certain: the attention paid to others and interpersonal relations are at the heart of a biennial that seeks to show how recent upheavals (societal, geopolitical) have impacted on human morale, and how art seizes on these questions, failing to provide solutions.

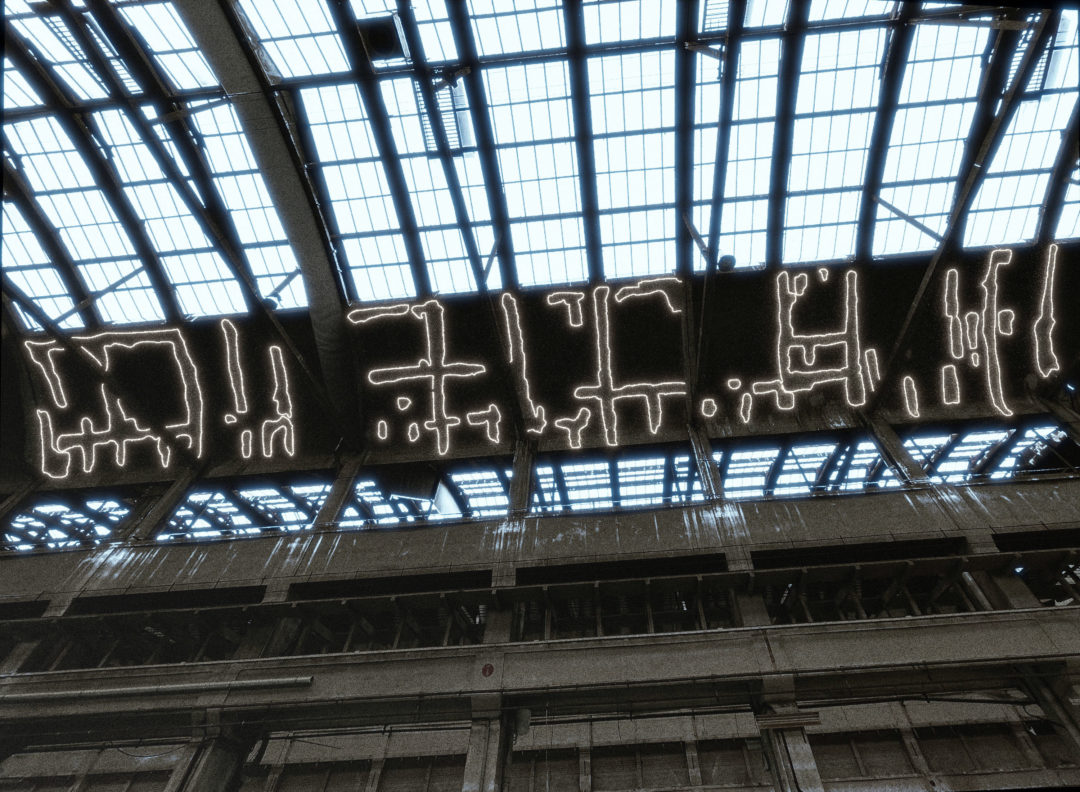

When we entered the biennial’s main site, the Grandes Locos, we were overwhelmed by a sense of crush and déjà vu: that of concrete cathedrals destined to be reinvested by a less polluting industry, that of culture. The works by Quebec artist Michel de Broin – highlighted with string lights and hastily applied sealants on the hall’s ceilings – bear witness to the end of a once flourishing industrial activity and the concomitant disappearance of a hard-working population steeped in a rich history. In the same vein, Pavel Büchler’s piece, which brings a joyful hubbub to the impressive refectory with its countless washbasins, underlines the ghostly character of premises that we once imagined rustling with a thousand sounds.

The gigantic scale of the site, combined with the ‘archipelagic’ nature of the works, creates a sense of floating, further accentuated by the claimed lack of authoritarianism on the part of the curator, who has preferred horizontality and fluidity to the assertive verticality of the gestures. It’s hard to escape the repertoire that runs through the many subsections of the theme: from the phenomenon of invisibility of black actors in cinema (Jérémie Danon & Kiddy Smile), in a joyful video that is free of radical protest but deliciously ironic (RIDE, 2024), to Nefeli Papadimouli’s ‘passage en textile’, which struggles to renew the experiments of Franz Erhard Walter ; from Iván Argote’s work (Un chemin commun, 2024), which is a little gentle and urges us to take each other by the hand, to Julien Discrit’s installation, which proposes to revisit the approach to Alzheimer’s disease through a subtle immersion in memory rather than the usual violence of hospital treatment (Forever Reverb). The general ambience of this first site, filled with works that celebrate attentive postures – sometimes quite literal (coat 4 by Liesl Raff) – is not always so ‘care-ssing’, however, and allows the disappointing messages of a Nathan Coley (There will be no miracles) to flicker through. But it’s the more offbeat works that leave the most lasting impressions, like Hans Schabus’s interminable wooden tunnel that teleports us from one side of the Grands Locos to the other, or Jean-Christophe Norman’s magnificent pictorial installation, a transposition in so many micro-paintings of the thousand pages of Hans Henny Jahnn’s whirlwind novel. Argote’s oversized swing (The others, we and the others, 2023), which returns to his penchant for the absurd and his gentle critique of human relationships, is our favourite, as is the video by Lithuanian Andrius Arutiunian, which follows in the footsteps of Michael Snow by creating an undeniable island of temporal suspension. The second site of the Grandes Locos is largely dominated by the impressive work of Oliver Beer: the highlight of this biennial leaves aside the banners of Jeremy Deller, as well as the work of Seulgi Lee, which would have deserved more visibility. But it has to be said that the British artist’s multiprojection leaves us in awe of an immersive installation with perfectly mastered acoustics. It envelops us in the voices recorded in the Palaeolithic caves where the artist asked eight performers to sing the songs that marked their childhood, plunging us into a sonic and visual universe that resonates with architecture and music, memory and history.

In fact, as the curator suggested during her presentation, the Grandes Locos and the Cité de la Gastronomie – another of the biennial’s new sites – were home to works that could be described as benevolent and ‘restorative’, while the Mac presented works that were more tense, bearing witness to the darker side of human relationships. At the museum, the visit begins with the screening of an extract from Chantal Akerman’s film (In the mirror), in which the nude female character contemplates her body and wonders about her figure. The tone is set by the filmmaker, who expresses all the anxiety that physical appearance can generate: the issues of self-acceptance and relationships with others are masterfully condensed into a single sequence shot. We then move on to a room dedicated to the regretted Sylvie Fanchon, whose minimalist canvases, weighted down with inscriptions, resonate with a troubled age when technology seems to offer no guarantee of social progress.

Omer Fast’s films, Tirdad Hashemi & Sofiane Erfanian’s drawings, and Taysir Batniji’s installation, each in their own way, heighten this sense of living in uncertain times when wars seem to have no end and inhumanity to develop accordingly. As for interpersonal relationships, Lorraine de Sagazan and Tohé Commaret paint a portrait of a world still marked by male domination and the objectification of bodies. Grace Ndiritu’s monumental installation contradicts this pessimistic vision, restoring a little hope and a place for women in an art history that has largely ignored them, as do the works on display at the new Cité de la Gastronomie site, which create a much more optimistic, if somewhat more literal, atmosphere (Guadalupe Maravilla), preferring the organic, more polysemous forms of Hajar Satari.

Head image : Hans Schabus, Monument for People on the Move, 2024. Bois, fonte d’aluminium. Courtesy de l’artiste. Création pour la 17e Biennale de Lyon. © ADAGP, Paris, 2024. Photo Jair Lanes”

- From the issue: 109

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Hilma af Klint, Playground, Anozero' 24, Coimbra Biennal, Signs and Objects. Pop art from the Guggenheim Collection at Guggenheim Museum, Momentum 12 at Moss,

Related articles

Ralph Lemon

by Caroline Ferreira

Ho Tzu Nyen

by Gabriela Anco

Hilma af Klint

by Patrice Joly